The Bird Feather Cloak of Captain James Cook

This Hawaiian feathered cloak and helmet were given to British explorer Captain James Cook in 1779.

Kalani'opu'u, high chief on the island of Hawaii, took off the cloak that he was wearing and put it, along with this helmet, on Cook. The Hawaiians believed Cook was an incarnation of their supreme god, Lono.

Not only were the feathers beautiful, they were a connection to the gods. Red feathers were particularly sacred. Yellow feathers came from the 'Ō'ō and Mamo birds. These birds only had a few yellow feathers, which were plucked out - then the birds were set free. The 'Ō'ō is now extinct, the victim of hunting following European entry to Hawaii in the 1800s. The red feathers came from the i'iwi bird. In total, it probably took feathers from more than 20 000 birds to make this cloak.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Display, Te Papa Museum, Wellington

Additional text: Wikipedia

New Zealand has now (2020) formally repatriated an intricately woven ʻahu ʻula (feathered cloak) and a brightly colored mahiole (helmet) that changed hands during a pivotal moment in Hawaiian history, officials announced last week.

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa), which has housed the artifacts since 1912, returned the attire to Honolulu’s Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum on long-term loan in 2016. Now, a joint partnership between the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) and the two museums has ensured the cloak and helmet will remain in Hawaiʻi "in perpetuity."

Hawaiian Chief Kalaniʻōpuʻu gave the garments to British explorer James Cook during a fateful meeting in Kealakekua Bay in late January 1779. Cook’s then-lieutenant, James King, described the encounter in his journal, writing that the chief "got up & threw in a graceful manner over the Captn’s Shoulders the Cloak he himself wore, & put a feathered Cap upon his head."

text above: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/cloak-helmet-hawaii-captain-cook-180975298/

When Captain James Cook visited Hawaii on 26 January 1778 he was received by a high chief called Kalani'ōpu'u. At the end of the meeting Kalani'ōpu'u placed the feathered helmet and cloak he had been wearing on Cook. Kalani'ōpu'u also laid several other cloaks at Cook's feet as well as four large pigs and other offerings of food. Much of the material from Cook's voyages including the helmet and cloak ended up in the collection of Sir Ashton Lever. He exhibited them in his museum, the Holophusikon. It was while at this museum that Cook's mahiole and cloak were borrowed by Johann Zoffany in the 1790s and included in his painting of the Death of Cook.Text above: Wikipedia

Lever went bankrupt and his collection was disposed of by public lottery. The collection was obtained by James Parkinson who continued to exhibit it, at the Blackfriars Rotunda. He eventually sold the collection in 1806 in 7 000 separate sales.

The mahiole and cloak were purchased by the collector William Bullock who exhibited them in his own museum until 1819 when the collection was again sold. The mahiole and cloak were then purchased by Charles Winn along with a number of other items and these remained in his family until 1912, when Charles Winn's grandson, the Second Baron St Oswald, gave them to the Dominion of New Zealand. They are now in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Close up of a similar helmet to the one above.

Photo: https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/exam-2-arth-3790/deck/5726857

This is another cape given to Cook.

Cape of netted fibre and feathers, collected from Hawaii in 1778 during Cook's third voyage to the Pacific. This one is unusual in its use of the long tail feathers of red and white tropical birds and black cock feathers. At least 30 feathered cloaks and capes were collected. On the occasion of Cook's official welcome by Kalani'opu'u, six or seven cloaks and other feather items were presented to him.

Photo: This object is from the collections of the Australian Museum.

Catalog: H000104

Text: Wikipedia

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Male and female Moho nobilis - Hawaii Ō'ō

The Hawaii 'Ō'ō was first described by Blasius Merrem in 1786. It had an overall length of 32 centimetres (13 in), wing length of 11–11.5 centimetres (4.3–4.5 in), and tail length of up to 19 centimetres (7.5 in).

The colour of its plumage was glossy black with a brown shading at the belly. It was further characterized by yellowish tufts at the axillaries. It had some yellowish plumes on its rump, but lacked yellow thigh feathers like the Bishop's 'Ō'ō, and also lacked the whitish edgings on its tail feathers like the O'ahu 'Ō'ō. However it had the largest yellow plumes on its wings out of all the species of 'Ō'ō.

At the time of discovery by Europeans, it was still relatively common on the Big Island, but that was soon to change. The Hawai'i 'Ō'ō was extensively hunted by Native Hawaiians. Its striking plumage was used for 'a'ahu ali'i (robes), 'ahu 'ula (capes), and kāhili (feathered staffs) of ali'i (Hawaiian nobility). The Europeans too saw the striking beauty of this bird and hunted many of them for specimens in personal collections. Some were even caught and put in cages to be sold as song birds only to live for a few days or weeks before diseases from mosquitoes befell them.

The decline of this bird was hastened by both natives and Europeans by the introduction of the musket which allowed hunter and collectors to shoot birds down from far away places and from great heights and numbers. As late as 1898, hunters were still able to kill over a thousand of the birds, but after that year the 'Ō'ō population declined rapidly. The birds became too rare to be shot in any great quantities, but continued to be found for nearly 30 years. The last known sighting was in 1934 on the slopes of Mauna Loa.

Artist: John Gerrard Keulemans (1842–1912)

Date: 1893

Source http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/nhrarebooks/rothschild/CF/description-search-results-all.cfm

Permission: Public Domain

Text: Wikipedia

The 'i'iwi (Vestiaria coccinea ), is a 'hummingbird-niched' species of Hawaiian honeycreeper and the only member of the genus Vestiaria . It is one of the most plentiful species of this family, many of which are endangered or extinct. The 'i'iwi is a highly recognisable symbol of Hawai'i. The 'i'iwi is the third most common native land bird in the Hawaiian Islands. Large colonies of 'i'iwi inhabit the islands of Hawaiii and Kauaii, with smaller colonies on Moloka'i and O'ahu but are no longer present on Lāna'i. Altogether, the remaining populations total 350 000 individuals, but are decreasing.

The adult 'i'iwi is mostly scarlet, with black wings and tail and a long, curved, salmon-coloured bill used primarily for drinking nectar. The contrast of the red and black plumage with surrounding green foliage makes the 'i'iwi one of Hawai''s most easily seen birds. Younger birds have golden plumage with more spots and ivory bills and were mistaken for a different species by early naturalists.

Although it was used in the feather trade, it was less affected than the Hawai'i mamo because it was not as sacred to Hawaiians. The 'i'iwi's feathers were highly prized by Hawaiian ali'i (nobility) for use in decorating 'ahu'ula (feather cloaks) and mahiole (feathered helmets), and such uses gave the species its scientific name, Vestiaria, which comes from the Latin for 'clothing', and coccinea meaning 'scarlet-colored'. The bird is often mentioned in Hawaiian folklore.

The bird can hover, much like a hummingbird. Its peculiar song consists of a couple of whistles, the sound of balls dropping in water, the rubbing of balloons together, and the squeaking of a rusty hinge.

Photo: © US Forest Service

Source: http://www.hawaiireporter.com/invasive-species-control-threatens-endangered-native-birds-the-case-of-the-iiwi-and-the-banana-poka

Text: Wikipedia

Kalaniopuu, King of Hawaii, (Tereoboo on the engraving) bringing presents to Captain Cook.

The engraving shows a Hawaiian canoe with a 'crab-claw' sail and many oarsmen, carrying Kalaniopuu, the Hawaiian chief, to visit Captain Cook aboard the 'Resolution'.

The main canoe, an outrigger, is followed by two double-hulled canoes without sails, full of oarsmen, and one boat is carrying wrapped carved figures. The Hawaiian coastal hills can be seen in the right background.

Artist: John Webber (1751–1793), drawn 1779, published 1784

Permission: Public Domain

Source: Wikipedia

Text: Wikipedia

Artist: Nathaniel Dance, 1775-76

Permission: Public Domain via Wikipedia

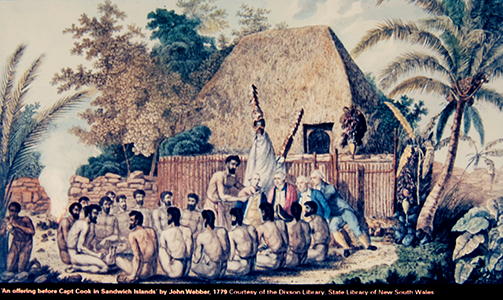

'An offering before Capt Cook in Sandwich Islands' by John Webber, 1779.

Samwell continued:

'To day a Ceremony was performed by the Priests in which he was invested by them with the Title and Dignity of Orono, which is the highest Rank among these Indians and is a Character that is looked upon by them as partaking something of divinity; The Scene was among some cocoa nut Trees close by Ohekeeaw, before a sacred building which they call 'Ehare no Orono' or the Temple of Orono.

Captn Cook attended by three other Gentlemen was seated on a little pile of Stones at the foot of an ill formed Idol stuck round with rags and decayed Fruit, the other Gentlemen sat on one side of him and before him sat several Priests and behind them a number of Servants with a barbequed Hog.'

King was 'here again made to support the Captains Arms, & after dressing him, a young pig was brought by Koah, (when they went thro' a deal of ceremony in presenting it to him, he & about a dozen standing in a line;)… afterwards the Performers sat down, Kava was made & presented'.

Artist: John Webber (1751–1793)

Source: Display, Te Papa Museum, Wellington

Additional text: http://www.captaincooksociety.com/home/detail/225-years-ago-january-march-1779

Cook and the Hawaiian Islands

On his last voyage, Cook again commanded HMS Resolution, while Captain Charles Clerke commanded HMS Discovery. The voyage was ostensibly planned to return the Pacific Islander, Omai to Tahiti, or so the public were led to believe. The trip's principal goal, however, was to locate a Northwest Passage around the American continent.Text above: Wikipedia

After dropping Omai at Tahiti, Cook travelled north and in 1778 became the first European to begin formal contact with the Hawaiian Islands. After his initial landfall in January 1778 at Waimea harbour, Kauai, Cook named the archipelago the 'Sandwich Islands' after the fourth Earl of Sandwich - the acting First Lord of the Admiralty. From the Sandwich Islands Cook sailed north and then north-east to explore the west coast of North America north of the Spanish settlements in Alta California.

Cook returned to Hawaii in 1779. After sailing around the archipelago for some eight weeks, he made landfall at Kealakekua Bay, on 'Hawaii Island', largest island in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Cook's arrival coincided with the Makahiki, a Hawaiian harvest festival of worship for the Polynesian god Lono. Coincidentally the form of Cook's ship, HMS Resolution, or more particularly the mast formation, sails and rigging, resembled certain significant artefacts that formed part of the season of worship. Similarly, Cook's clockwise route around the island of Hawaii before making landfall resembled the processions that took place in a clockwise direction around the island during the Lono festivals. It has been argued (most extensively by Marshall Sahlins) that such coincidences were the reasons for Cook's (and to a limited extent, his crew's) initial deification by some Hawaiians who treated Cook as an incarnation of Lono.

After a month's stay, Cook attempted to resume his exploration of the Northern Pacific. Shortly after leaving Hawaii Island, however, the Resolution's foremast broke, so the ships returned to Kealakekua Bay for repairs.

Tensions rose, and a number of quarrels broke out between the Europeans and Hawaiians at Kealakekua Bay. An unknown group of Hawaiians took one of Cook's small boats. The evening when the cutter was taken, the people had become 'insolent' even with threats to fire upon them. Cook was forced into a wild goose chase that ended with his return to the ship frustrated. He attempted to kidnap and ransom the King of Hawai'i, Kalani'ōpu'u.

That following day, 14 February 1779, Cook marched through the village to retrieve the King. Cook took the ali'i nui by his own hand and led him willingly away. One of Kalani'ōpu'u's favorite wives, Kanekapolei and two chiefs approached the group as they were heading to boats. They pleaded with the king not to go until he stopped and sat where he stood. An old Kahuna (priest), chanting rapidly while holding out a coconut, attempted to distract Cook and his men as a large crowd began to form at the shore. The king began to understand that Cook was his enemy.

As Cook turned his back to help launch the boats, he was struck on the head by the villagers and then stabbed to death as he fell on his face in the surf. He was first struck on the head with a club by a chief named Kalaimanokaho'owaha or Kana'ina (namesake of Charles Kana'ina) and then stabbed by one of the king's attendants, Nuaa. The Hawaiians carried his body away towards the back of the town, still visible to the ship through a spyglass. Four marines, Corporal James Thomas, Private Theophilus Hinks, Private Thomas Fatchett and Private John Allen, were also killed and two others were wounded in the confrontation.

The esteem which the islanders nevertheless held for Cook caused them to retain his body. Following their practice of the time, they prepared his body with funerary rituals usually reserved for the chiefs and highest elders of the society. The body was disembowelled, baked to facilitate removal of the flesh, and the bones were carefully cleaned for preservation as religious icons in a fashion somewhat reminiscent of the treatment of European saints in the Middle Ages. Some of Cook's remains, thus preserved, were eventually returned to his crew for a formal burial at sea.

Clerke assumed leadership of the expedition, and made a final attempt to pass through the Bering Strait. Following the death of Clerke, Resolution and Discovery returned home in October 1780 commanded by John Gore, a veteran of Cook's first voyage, and Captain James King. After their arrival in England, King completed Cook's account of the voyage. David Samwell, who sailed with Cook on the Resolution, wrote of him: 'He was a modest man, and rather bashful; of an agreeable lively conversation, sensible and intelligent. In temper he was somewhat hasty, but of a disposition the most friendly, benevolent and humane. His person was above six feet high: and, though a good looking man, he was plain both in dress and appearance. His face was full of expression: his nose extremely well shaped: his eyes which were small and of a brown cast, were quick and piercing; his eyebrows prominent, which gave his countenance altogether an air of austerity.'

Death of Cook.

Photo: George Carter, 1783, Bernice P. Bishop Museum

Medium: Oil on canvas

Permission: Public Domain via Wikipedia

(left)

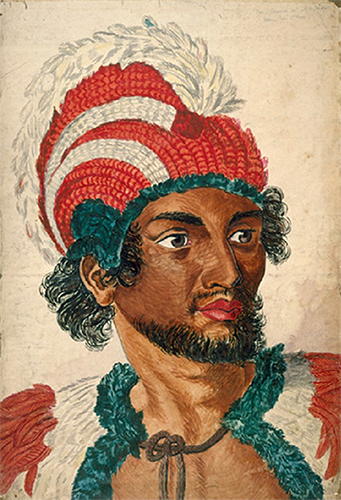

A coloured portrait based on the Portrait of Kaneena, a chief of the Sandwich Islands in the North Pacific by John Webber. The actual spelling is Kanaina, and he was one of the two chiefs along with Palea (Pareea) who were the first to greet Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay.

Described as fine as 'a figure as can be seen. He was about six feet high, had regular and expressive features, with lively dark eyes; his deportment was easy, firm, and graceful.'

According to Abraham Fornander he is possibly the person who struck the fatal blow that ended James Cook's life; he called him Kalanimanokahoowaha. According to another source he was one of the chiefs that died in the fighting.

Medium : watercolor

Dimensions 75 × 51 cm

Object history: Created in Hawaii, ca 1830 – 1839.

Part of the collection of 30 watercolours relating to the South Seas belonging to Rev. John Williams (1796 – 20 November 1839), which was used by him and his ministers when raising funds for the London Missionary Society.

Artist: Unknown, based on a portrait by John Webber

Current location: National Library of Australia, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Accession number nla.pic-an13864659.

Permission: Public Domain

(right)

'Portrait of Kaneena, a chief of the Sandwich Islands in the North Pacific' by John Webber. The actual spelling is Kanaina, and he was one of the two chiefs along with Palea (Pareea) who were the first to greet Captain Cook at Kealakekua Bay. Described as 'as fine a figure as can be seen. He was about six feet high, had regular and expressive features, with lively dark eyes; his deportment was easy, firm, and graceful.' According to Abraham Fornander he is possibly the person who struck the fatal blow that end James Cook's life, he called him Kalanimanokahoowaha. According to another source he was one of the chiefs that died in the fighting.

Artist: John Webber

Text: Wikipedia

Permission: Public Domain, via Wikipedia

References

Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Maori Culture Index

Back to Maori Culture Index