Back to Don's Maps

Mousterian (Neanderthal) Sites

Mousterian (Neanderthal) Sites Back to the review of hominins

Back to the review of hominins

Saint Césaire Neanderthal skeleton

Recreation of the Saint Césaire individual by Elizabeth Daynès, from http://limousin-poitou-charentes.france3.fr/dossiers/42693930-fr.php

The dig at Saint Césaire.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

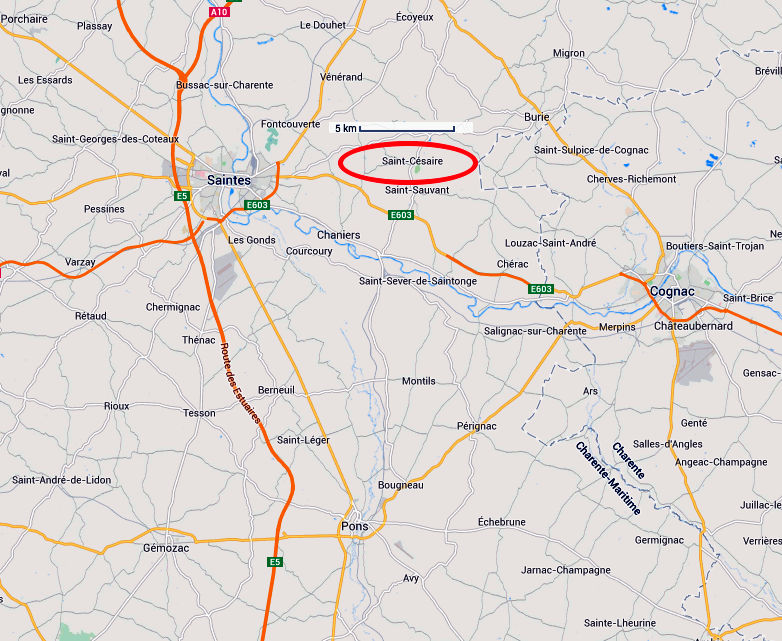

Saint Césaire lies between Saintes and Cognac.

Photo: Google Maps

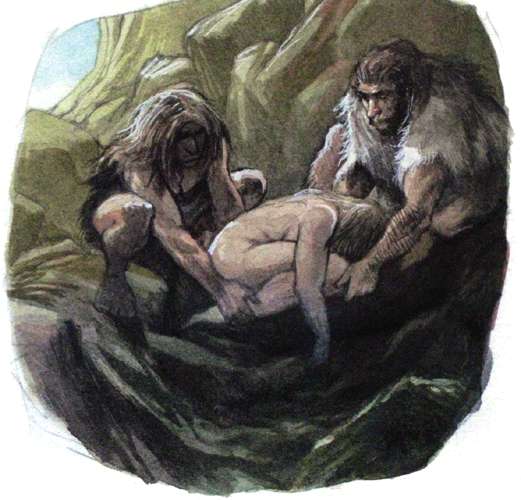

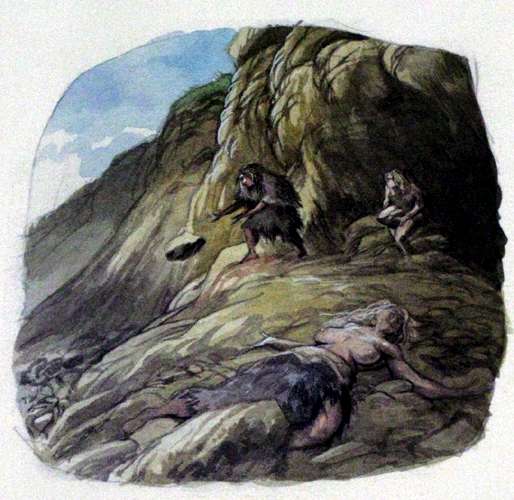

This exceptional burial exhumed in 1979 in Charente-Maritime combines for the first time an incomplete skeleton of a Neanderthal and the Châtelperronien tool industry dated at about 36 000 years.

The individual, perhaps a young woman, showed the scars of a severe cranial injury of traumatic origin, partially healed.

The body was completely within a circular area of 70 cm in diameter, probably built intentionally, but no pit has been detected in the search.

Text: Adapted and translated from the display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Artist:© Emmanuel Roudier, 2008

Superb watercolours were done for this exhibition by the French artist, Emmanuel Roudier.

Blog: http://roudier-neandertal.blogspot.com/ Contact: emmanuelroudier@gmail.com

Source: Display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Cette exceptionnelle sépulture exhumée en 1979 en Charente-Maritime associe pour la première fois un squelette néandertalien incomplet à une industrie du Châtelperronien datée d'environ 36 000 ans.

L'individu, peut-être une jeune femme présentait les stigmates d'une grave blessure crânienne, d'origine traumatique, partiellement cicatrisée.

Le corps était circonscrit dans une espace circulaire de 70 cm de diamètre sans doute aménagé intentionnellement, mais aucune fosse n'a été détectée à la fouille.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Artist:© Emmanuel Roudier, 2008

Superb watercolours were done for this exhibition by the French artist, Emmanuel Roudier.

Blog: http://roudier-neandertal.blogspot.com/ Contact: emmanuelroudier@gmail.com

Source: Display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

The woman of Saint Césaire

(note that this photo has been altered from the original superb work of art by Claire Artemyz.

Here is the original - Don )

Photo: © Claire Artemyz, http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/memoires/index.php

The woman of Saint Césaire.

Facsimile

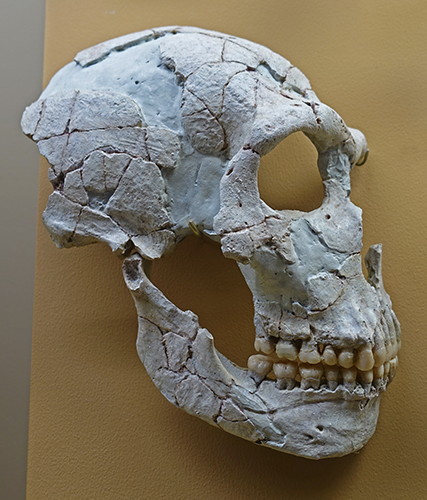

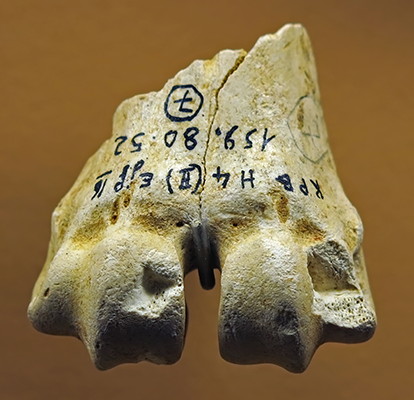

The skeleton was associated with a lithic industry from the Châtelperronien. The analysis of the proportions of carbon and nitrogen in the collagen of the human bones of the Saint Césaire skeleton shows that the individual was essentially a carnivore. As well, after a thorough examination of the skull, researchers found evidence of a scar 6 cm long on the right side of the skull which was the result of a violent blow.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Display, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire skull.

Original, circa 36 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Collections du Musée d'Archéologie nationale - Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Pierrette la Néandertalienne de Saint-Césaire.

The skull is now known as la Pierrette, since it is believed to be female.

Facsimile.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

This facsimile is catalogued as:

Homo neanderthalensis 'Pierrette' ~ 35 000 ans Saint-Césaire, Charente-Maritime.

However, it is at first sight something of an enigma, because both sides of the skull are shown, whereas only one side of the skull was found. The rest of the skull has been created using mirroring of the existing bones where necessary, see the image below.

If the reader zooms in on the images by clicking on them, they will see that the facsimile has been constructed using a 3D printer, since the layers by which models are built up using this method are clearly visible.

This method has become hugely useful in the study of anthropology, since the scan of the object can be sent by email or other file transfer to anyone with a 3D printer, who can print their own faithful copy of the one in the original museum for further study.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

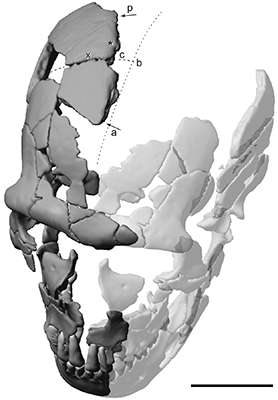

Computerized reconstruction of the St. Césaire 1 Neanderthal skull (mirror-imaged completed parts are transparent) showing the bony scar in the right apical cranial vault. The skull is seen from the direction in which the hypothetical blow was exerted.

Arrows indicate the anteroposterior (a and p) extent of the preserved lateral border of the injury (c, coronal suture; b, bregma; *, location of the coronal cross section through the injury.

×, location of the parasagittal cross section through the coronal suture; the dotted line indicates the reconstructed position of the midsagittal plane of the cranial vault). Note oblique, off-midline position of the scar. (Scale bar = 5 cm.)

Photo and text: Zollikofer et al. (2002)

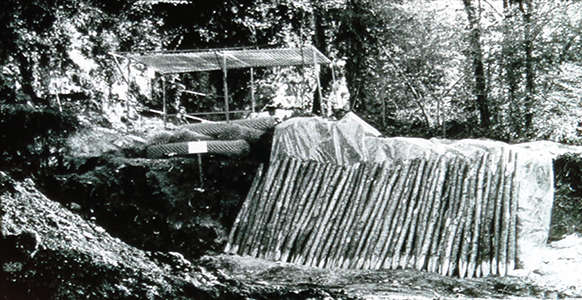

The dig at Saint Césaire.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Third left upper molar of a megaloceros.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Third phalanx of a horse.

The coffin bone, also known as the pedal bone (U.S.), is the bottommost bone in the equine leg and is encased by the hoof capsule. Also known as the distal phalanx, third phalanx, or 'P3'

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Third upper premolar right tooth of a rhinoceros.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015, 2018

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Distal end of a reindeer metacarpal bone

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Reindeer antler.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Grattoirs or scrapers on what have become known as 'strangled' blades, blades constricted with notches. These are very common in the Aurignacian.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Grattoir or scraper on a blade.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Aurignacian industries

Grattoir caréné, or keeled scraper.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

The site of Saint-Césaire has delivered numerous flakes and flint tools from different archaeological times: Mousterian, Châtelperronian and Aurignacian.Text above: Translated from a display at the Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

The lithic industry of the Châtelperronian has produced lively debate. Indeed, it is composed of a majority of grattoirs and racloirs characteristic of the Mousterian, and some backed pieces more properly from the Châtelperronian.

Archaeologists ask: is this an archaic Châtelperronian or a mixture of archaeological beds?

Because of the fragmentation (more than 500 pieces of bone) and their fragility, the Pierrette skeleton was encased in plaster and removed with accompanying sediment in one block, before being studied in the laboratory. This analysis of the skeleton has revealed the presence of a mosaic of neanderthal characteristics as well as an important healed wound to the head.

Saint Césaire Châtelperronian industries

Châtelperronian knives.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Châtelperronian industries

This is labelled as a grattoir, a scraper.

( I think it would more accurately be called a racloir, a side scraper, which is a common part of the Mousterian toolkit. Note also the flake taken out which would have fit a thumb well, making the tool easier to use, another feature of many Mousterian scrapers - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Châtelperronian industries

Racloir (side scraper) with convergent edges, created using a Levallois point as the blank.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Châtelperronian industries

Leaf point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Châtelperronian industries

Biface hand axe.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Mousterian industries

(left): Horse astragal or ankle.

(centre): Distal end of the tibia of a reindeer.

(right): Second phalanx of a bison.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Mousterian industries

Denticulate racloir.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Display, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Saint Césaire Mousterian industries

(left): Biface hand axe.

(right): Backed knife.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Display, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Perçoir sur lame

Awl or drill made on a blade.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

Lamelles à dos

Small backed blades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

Racloir simple à retouche

A single scraper retouched.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

Racloirs convexes

Convex scrapers - the one on the left is a double convex scraper, having a convex form on two sides.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

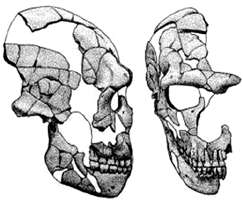

Homo neanderthalensis

Partial cranium (facsimile)

Saint Césaire, France, ca 36 000 BP

Photo: Ralph Frenken

Source: Museum of Natural History, Vienna, Austria

Tools found at the Saint Césaire site. It consists of a Châtelperronian tool kit, which is normally associated with Homo sapiens sapiens, not Neanderthal. This is seen by some as coexistence in a particular area, and trading of techniques between Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon.

Computer-tomographic imaging and computer-assisted reconstruction have also revealed a healed fracture of the skull.

At 36 000 years BP, the Saint Césaire neanderthal is the latest Neanderthal known in France, proof that Neanderthals survived into the early Upper Paleolithic, contrary to what had been believed up to the time of discovery.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Casts on display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Cast of the Saint Césaire skeleton in situ when it was first discovered.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Cast on display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Skull, clavicle and humerus of the Saint Césaire I skeleton. Only one half of the skull is complete.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Originals, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Reconstruction of the Saint Césaire skull

Photo: http://www.mpg.de/bilderBerichteDokumente/dokumentation/pressemitteilungen/2004/pressemitteilung20040123/index.html

A radius and ulna, as well as a femur, patella and other leg bones were recovered.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Originals, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Posterior view of the Saint-Césaire 1 right femoral proximal diaphysis. Scale in centimetres.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 May 12; 95(10): 5836–5840.

Copyright © 1998, The National Academy of Sciences

Photo: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=20466

In 1975, earthworks to facilitate the passage of trucks carrying mushrooms unearthed some flints and animal bones. The first to see these was an amateur prehistorian, Bernard Dubiny. He was on his way to fish for trout, and stopped to have a look at the road cutting. Although the area was not known as a prehistoric site, he persuaded the owner of the cutting, the mayor of Saint-Césaire, René Boucher, to stop work on the cutting immediately.

Quickly, a team of archaeologists formed around Francois Lévêque. Four years later, the work was rewarded by the discovery of human Neanderthal remains that the CNRS laboratories dated at only 36 000 years BP, which meant that it was possible that there had been several millennia of coexistence between Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons.

The collapsed rock shelter, or abri, was called La Roche-à-Pierrot, since the name given to the twenty year old Neanderthal was Pierrot. However it may be that the original Neanderthal was a woman. Local usage has now changed the name to Pierrette, in recognition of the uncertainty. A further interesting fact is that the skull shows signs of a healed injury, and locals speculate that Pierrette may have been a battered wife! Not very scientific, perhaps, but the skeleton has been very good for the local economy, bringing many tourists every year, and any spin publicists can make up is seized upon.

Photo: http://www.kterre.org/chronologie/info.php?id=919

Note: I have flipped the left hand, coloured image horizontally - it is amazing how many times images are wrongly shown in this way. It is only the right hand side of the skull which has been recovered. - Don

Text: translated and adapted from www.julien-labruyere.eu/media/2005__054460600_1615_13022008.pdf

The site in 1977, after the cessation of earthmoving, and during the early work of excavation at the site.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

(left) Protection of the gisement from the elements in 1977.

(right) Protection of the workers at this time was, however, minimal, and full wet weather gear was sometimes essential.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

The discovery of Pierrette in 1979.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

The skeleton was carefully separated from the rest of the layer, and the whole thing was covered in plaster for removal in toto from the site to a laboratory.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display, Paléosite at Saint Césaire.

From: http://www.pnas.org/content/99/9/6444.abstract

Evidence for interpersonal violence in the St. Césaire Neanderthal

Authors: Christoph P. E. Zollikofer, Marcia S. Ponce de León, Bernard Vandermeersch, and François Lévêque

Abstract

The St. Césaire 1 Neanderthal skeleton of a young adult individual is unique in its association with Châtelperronian artifacts from a level dated to ca. 36 000 years ago. Computer-tomographic imaging and computer-assisted reconstruction of the skull revealed a healed fracture in the cranial vault. When paleopathological and forensic diagnostic standards are applied, the bony scar bears direct evidence for the impact of a sharp implement, which was presumably directed toward the individual during an act of interpersonal violence. These findings add to the evidence that Neanderthals used implements not only for hunting and food processing, but also in other behavioral contexts. It is hypothesized that the high intra-group damage potential inherent to weapons might have represented a major factor during the evolution of hominid social behavior.

Left, a recreation of the Abri Saint Césaire, also known as La Roche-à-Pierrot, where the Neanderthal skeleton was discovered, at the Paléosite at Saint Césaire (which opened on May 27 in 2005, and had 65 000 visitors in 2007).

The original is a collapsed rock shelter at the foot of a limestone cliff 5 to 6 metres high in a valley which runs north-south on a small river, the Coran, a tributary of the Charente.

Right, a cast at the Paléosite of the skeleton at the time of its discovery.

Photo:

http://www.paleosite.fr/pages/entrez.php#BATIMENT

This is a token or jeton from the Paléosite using an image of Pierrette, found at Ebay. Note that the image on the token has been switched horizontally:

For those interested in going to this site, here is some relevant information from the Paléosite website:

Localisation : 17770 St Césaire (Charente-Maritime)

Localisation : 17770 St Césaire (Charente-Maritime)Ouverture :

- Avril, Mai, juin et Septembre : de 10h à 19 h.

- Juillet, Août : de 10h à 20h.

- Octobre à Mars : de 10h30 à 18h.

- Janvier : fermeture du site

Tarifs

- Adultes : 10 euros

- Enfants 5 à 14 ans : 6 euros

- Pass Famille : 26 euros (2 adultes et 2 enfants)

- Pass Fidélité : 30 euros (1 adulte pour un an)

- Gratuits pour les enfants de moins de 5 ans. Actualités

0 810 130 134

Site web:

www.paleosite.fr

Text and graphics below adapted from:

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2224228

The Saint-Césaire Faunal Record

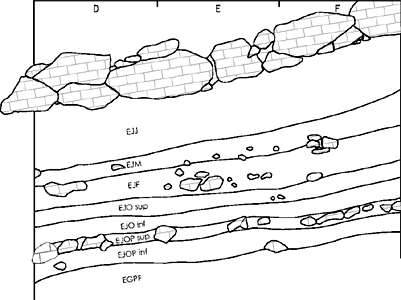

In 1979, a Neanderthal skeleton was found at the base of a limestone cliff at Saint-Césaire in Charente-Maritime, France, associated with Châtelperronian artifacts, an EUP (Early Upper Palaeolithic) industry then attributed to modern humans. This finding had important repercussions because it indicated that Neanderthals were involved in the emergence of the Upper Paleolithic.Further work at Saint-Césaire revealed a high-resolution stratigraphy covering the full span of the M/UP (Middle to Upper Palaeolithic) transition. Fifteen occupations, thermoluminescence-dated between 30 000 and 43 000 BP, along with several thousand artifacts and animal remains were uncovered during the excavations. In this sequence, levels EGPF through EJJ are particularly important because they document the M/UP boundary. Level EGPF corresponds to a Denticulate Mousterian occupation, EJOP sup to a Châtelperronian occupation, EJO sup to a Proto-Aurignacian occupation, EJF to an Early Aurignacian occupation, and EJM and EJJ to two distinct Evolved Aurignacian occupations. EJOP inf and EJO inf are small occupations for which the cultural attribution is less secure.

The Saint-Césaire stratigraphy.

From bottom to top:

EGPF corresponds to a Denticulate Mousterian occupation, EJOP sup to a Châtelperronian occupation, EJO sup to a Proto-Aurignacian occupation, EJF to an Early Aurignacian occupation, and EJM and EJJ to two Evolved Aurignacian occupations. EJOP inf and EJO inf are small occupations with unclear cultural attribution.

Diagram of stratigraphy from:

Lévêque, F; Backer, AM; Guilbaud, M. Context of a Late Neandertal: Implications of Multidisciplinary Research for the Transition to Upper Paleolithic Adaptations at Saint-Césaire, Charente-Maritime, France. Madison, WI: Prehistory Press; 1993.

The abundance of burned and cut-marked specimens and the low incidence of carnivore remains and carnivore-modified bones in the faunal samples indicate that humans were the main accumulators of the faunal remains at Saint-Césaire. Furthermore, the high δ15N value found in western European Neanderthals, including the St Césaire 1 specimen, indicate that most of their dietary proteins came from large herbivores. This finding strengthens the use of the Saint-Césaire fauna for examining changes in human population densities in Late Pleistocene Europe. Lastly, a study of bone refits has shown that occupation mixing has been limited at Saint-Césaire. These results support the potential of the stratigraphy of this site for addressing fine-grain research questions.

Reindeer, steppe bison, and horse represent 96% of total species composition for the Saint-Césaire occupations (Table 2). These three species are well represented in the Denticulate Mousterian (EGPF), Châtelperronian? (EJOP inf), and Châtelperronian (EJOP sup) occupations. In contrast, reindeer increased dramatically in abundance in the overlying Aurignacian occupations, reaching percentages from 69% to 85%. This increase is highly significant (Châtelperronian versus Proto-Aurignacian; ts = 23.27, P < 0.0001).

Table 2

|

Mousterian EGPF |

Châtelperronian? EJOP inf. | Châtelperronian EJOP sup. | Proto-Aurignacian EJO sup. | Aurignacian I EJF | Evolved Aurignacian EJM | Evolved Aurignacian EJJ | |

| Large species | (n = 866) | (n = 285) | (n = 803) | (n = 411) | (n = 3432) | (n = 829) | (n = 327) |

| Reindeer | 24.7 | 33.0 | 20.2 | 84.9 | 82.3 | 72.4 | 69.1 |

| Steppe bison | 38.0 | 35.8 | 48.7 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 9.4 | 11.9 |

| Red deer | 1.0 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 0.5 | 40.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Megaloceros | 0.8 | 0.4 | - | - | 0.2 | - | - |

| Roe deer | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Wild boar | - | 0.4 | 0.5 | - | 0.0 | - | - |

| Horse | 34.1 | 26.3 | 17.4 | 5.4 | 11.2 | 13.6 | 17.4 |

| Wooly rhino | 0.2 | 0.4 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | - |

| Wild ass | - | - | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Mammoth | 0.8 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.3 |

| Spotted hyena | 0.2 | - | 0.4 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.3 |

| Wolf | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Arctic fox | - | - | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | - | - |

| Polecat | - | - | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | - | - |

| Pine marten | - | - | - | 0.5 | - | - | - |

| Lynx | - | - | - | - | 0.0 | - | - |

| Badger | - | - | - | - | 0.0 | 0.1 | - |

| Cave lion | - | - | 0.2 | - | 0.1 | - | - |

| Hare | - | - | - | 0.2 | - | - | - |

| Total | 99.9 | 100.2 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| Micromammals | (n = 9) | (n = 2) | (n = 38) | (n = 84) | (n = 69) | (n = 100) | (n = 109) |

| Narrow-skulled vole | 55.6 | 50.0 | 76.3 | 95.2 | 85.5 | 93.0 | 89.0 |

| Common vole | 22.2 | - | 10.5 | 1.2 | 1.4 | - | 6.4 |

| Ground squirrel | - | - | - | - | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Snow vole | 11.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Water vole | 11.1 | 50.0 | 13.2 | 3.6 | 11.6 | 4.0 | 0.9 |

| Pine vole | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.9 |

| Garden dormouse | - | - | - | - | - | 1.0 | - |

| Root/Male vole | - | - | - | - | - | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Collared lemming | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.9 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.9 | 100.0 | 99.9 |

Antlers excluded. Micromammal data are from Morin (25) and Marquet (28).

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 January 8; 105(1): 48–53.

Published online 2008 January 2. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709372104.Copyright © 2008 by The National Academy of Sciences of the USA

25 Morin, E. Ann Arbor: Univ of Michigan; 2004. PhD thesis.

28 Marquet, JC. Paléoenvironnement et Chronologie des Sites du Domaine Atlantique Français d'Âge Pléistocène Moyen et Supérieur d'Après l'étude des Rongeurs. Tours, France: Les Cahiers de la Claise; 1993.

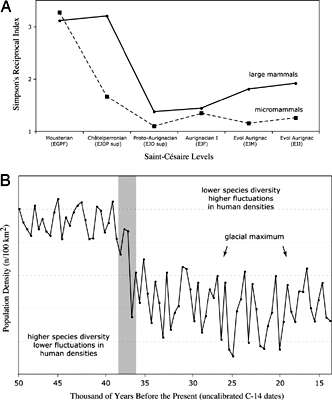

The temporal increase in reindeer abundance at Saint-Césaire is associated with a sharp decline in species diversity (Fig. 4a). This contraction of the species spectrum is consistent with the hypothesis of a climatic deterioration during the M/UP transition because it is not correlated with sample size (rs = −0.03, P > 0.05). However, cultural factors—for instance, specialisation on reindeer—also may explain these temporal patterns. To examine this possibility, micromammal species (<500 g) recovered from the Saint-Césaire occupations were used as control data and compared with the other larger species at the site. Micromammals are helpful because they typically represent background deposition in Pleistocene assemblages and are sensitive to subtle climatic changes (28).

Fig. 4

Faunal diversity at Saint-Césaire and its presumed impact on human densities. (A) Large mammal versus micromammal species diversity, as measured by the reciprocal of Simpson's index, in the Saint-Césaire levels. Data are from Table 2 (EJOP inf and EJO inf assemblages excluded because of small sample size). (B) Hypothetical reconstruction of fluctuations of hunter–gatherer densities in western Europe during the Late Pleistocene. The reconstruction is based on an extrapolation of the presumed effects of mammal diversity on human population densities. The shaded area shows the transition between the Châtelperronian and the Early Aurignacian.

Diagram of faunal diversity from:

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 January 8; 105(1): 48–53.

Published online 2008 January 2. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709372104.

Copyright © 2008 by The National Academy of Sciences of the USA

The narrow-skulled vole (Microtus gregalis), common vole (Microtus arvalis), and water vole (Arvicola terrestris) comprise 98% of the micromammal species identified at Saint-Césaire (Table 2). Other micromammal taxa (n = 6) are poorly represented. Today, the narrow-skulled vole is restricted to Palearctic tundra and wooded steppe habitats, whereas the common vole and water vole are typical of more temperate environments. If a climatic deterioration induced a decline in large species diversity during the EUP, the same factor is expected to have reduced micromammal species diversity as well, based on latitudinal trends in modern analogues. Furthermore, if the climatic hypothesis is correct, the trend toward increasing reindeer abundance at Saint-Césaire should be associated with a significant increase in the abundance of cold-adapted micromammals.

Both predictions are met by the data. The increasing abundance of reindeer in the Saint-Césaire sequence is matched by a concomitant increase in the abundance of the narrow-skulled vole, a cold-adapted species. Importantly, the decline in the diversity of large species in the EUP of Saint-Césaire is accompanied by a marked decline in micromammal species diversity (Fig. 4a). The correlation between micromammal species diversity and sample size is not statistically significant (rs = −0.77, P > 0.05). These data indicate that changes in faunal composition at Saint-Césaire were induced by increasingly cool climatic conditions. These faunal changes are in agreement with those observed at Roc de Combe and Grotte XVI in France, and they suggest that this climatic deterioration occurred on a regional scale. Additionally, the high number of reindeer-dominated Aurignacian assemblages in the same region lends support to the climatic deterioration inference.

References

- Zollikofer, C., Ponce de León, M., Vandermeersch, B., Lévêque, F., 2002: Evidence for interpersonal violence in the St. Césaire Neanderthal, PNAS, vol. 99 no. 9, 6444–6448, doi: 10.1073/pnas.082111899