Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

Rock paintings from Namibia in Africa. In Namibia these rock paintings and engravings were completed by San Bushmen.

Rock paintings from Namibia in Africa. In Namibia these rock paintings and engravings were completed by San Bushmen. South African Rock paintings in the Cedar Mountains

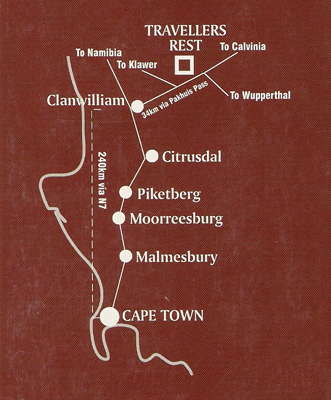

These paintings are near the Traveller's Rest, a lodge on a farm, http://www.travellersrest.co.za about 30 km east of Clanwilliam on the Wupperthal Rd. (R364) in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. I am very grateful to Michael Hess for these evocative photographs and text. The photos were taken in April 2004, and Michael Hess has provided the commentary, except where otherwise noted.

Location of Traveller’s Rest, coordinates 32°03’56,22S/19°04’48,49’’E at an altitude of 320 m altitude.

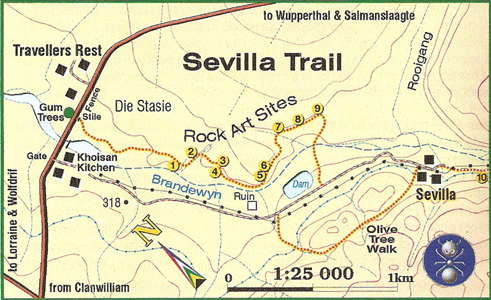

Photo: Slingsby 2000

This map shows the location of the Traveller's Rest accommodation area, and the San Rock Art along the Sevilla Trail. One has to ask for a permit (for a small fee) at the Traveller’s Rest and you receive a rough map indicating the locations. The Sevilla Trail on the terrain of the Sevilla Farm starts about 200 m downhill from the exit to Traveller’s Rest. Parking is at the huge gum tree at 32°04’10,53’’S/19°04’46,80’’E.

Walking the trail clockwise is not particularly difficult but counter clockwise requires some pathfinder’s qualities because the marks on the ground (white footprints) are difficult to see when travelling in that direction. This is really South Africa and not the Shire in Middle Earth with the Brandywine river (Baranduin), however, there is the ‘Khoisan Kitchen’ for meals and maybe even for a cold beer, an alternative South African version of the 'Prancing Pony' from 'Lord of the Rings'.

Photo: Slingsby 2000

Determining the age of the paintings is difficult in this area, because the stratigraphy has not been done, and the paintings are often in situations exposed to the weather. Most rock art is in abris. The paintings seem not to be as durable as the cave paintings of Europe, perhaps the artists did not use fat or other organic materials as a binder. White is a problem colour, it has often disappeared from the paintings, either washed off or absorbed by the rock, leaving behind obviously truncated human figures showing the well known 'hook head' or 'incomplete' animals. It should be possible to find out if the white colour really was absorbed by the rock using spectroscopic methods.

'Absorption by the rock' sounds to me not very conclusive, since diffusion in a crystalline solid such as is the case here is usually pretty slow, they do not usually dissolve substances at the surface easily. Flaking off appears to be a more likely reason for the disappearance of the white colour. Also, one type of black colour frequently fades away quite rapidly, while another black 'colour' is caused by lichens growing preferentially on certain pigments, so that we do not know what the original colour was.

Information about the chemical nature of the pigments is sparse and not very precise: suggested pigments are earth ochres, clay, ash (white?), bird droppings (white?), with egg-white, blood, urine and sap of plants possibly used as fixative. The colours are black, white, red, yellow (a really bright one! No idea what it might be; there are some yellow elephants at site 7 but the light was not good enough to take a photo), blue, and green have been found in San paintings. I only saw brown/ochre, black and yellow. The black is in some cases a ‘tar’ that is formed by decomposition of material in dassie middens. ( Dassie is the South African term for Rock Hyrax (Procavia capensis), which defecates in specific places, forming middens - Don ) , Another cause for a black ‘painting’ is the growing of a specific lichen on certain colours that it prefers, as mentioned above. There is some black lichen on fig. 6 and 7. After all, it seems that the nature of the colours is not well analysed.

Proper dating of the paintings is a problem. In Namibia, painted stones were found in stratigaphic layers of litter, and hence could be dated, going back as far as 27 500 years. Similar stones in South Africa date back more than 6 000 years.

Paintings with fat-tailed sheep cannot be older than 2 000 years ago because only at that time they were introduced by the Khoi-Khoi. Hand-prints and crude paintings appear to be younger than finely-drawn paintings because they always superimpose them. It seems that the San people lost their finely-detailed art of painting shortly after the arrival of the Khoi (or the San stopped painting and Khoi did the crude paintings?). There is some agreement that it is reasonable to date the majority of the paintings along the Sevilla Trail at least as old as 1 600 – 2 000 years, possibly as old as 8 000 years.

Hollow Rock Shelter, I think close to Site 1, is an archeological site (Middle Stone Age) where numerous 'projectile' tips and hand axes were excavated (1993 and 2008) and attributed to the so-called ’Still Bay Industry’ and as old as 72 000 – 80 000 years. So, modern man was around for already quite some time.

A few words about the San people might be useful here. The San people belong to the first ‘modern’ human inhabitants. In contrast to the other negroid, caucasoid or mongoloid modern humans, the San did not go 'out of Africa' but stayed behind and are probably closely related to the first 'true' humans (are we still 'human'? Sometimes I have my doubts looking at the daily news…). They were (still are, some of those who have survived) delicate hunters and gatherers co-existing with their environment, until, about 2 000 years ago, they were pushed into more remote and hostile parts by the herding Khoi-Khoi, who were pressing southward from the North and the herder-pastoralists (who are now the Ngui) from the East.

These encounters were apparently not exactly friendly for the Khoi-Khoi used names like 'obiekwa' (murderers) and ‘hawekwa’ (thieves) referring to the San. The use of the term 'Bushmen' is not recommended, although the San in Botswana and the Northern Cape prefer to be called 'Bushmen'. Now, follow me from Clanwilliam on the R364 direction Calvinia/Wupperthal back in time.

On the R364 between Pakhius Pass and the Brandewyn river, eastward bound.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

View to the East from Site 7 along the valley. Rain on the way.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

View to the South between Site 4 and 5.

The 'ruin' of the map is out of the picture to the right. Good lookout to the valley.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Abri at Site 5, view to the South West

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Black lichen at Site 7, view to the South. Another good look-out.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Site 2. Hook-headed dancers, in particular clearly visible on the second human figure from the right.

The dancers seem to clap their hands and small children might be playing around. There are three ‘blobs’.

According to Slingsby, these are interpreted as 'points of power' (???) 'from which the dancing shaman drew power from the rock and the painting'.

The animal to the left appears to be an example of the extinct quagga, which can be deduced from the colouring. The quagga is a subgroup of zebra and looks like a zebra-horse hybrid.

( Recent genetic research at the Smithsonian Institution has demonstrated that the quagga was, in fact, not a separate species at all, but diverged from the extremely variable plains zebra, Equus burchelli, between 120 000 and 290 000 years ago. The last wild quagga was probably shot in the late 1870s, and the last specimen in captivity, a mare, died on August 12, 1883 at the Natura Artis Magistra zoo in Amsterdam - WIkipedia )

There is a fat-legged human figure left of the blob and further left another faint quagga. There is a small animal painted nearby that could be interpreted as a bat-eared fox or a baboon.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Drawing of a bat-eared fox, from Slingsby 2000

Site 6: Seven dancing steatophytic women, some of them with digging sticks. Very faint figures are to the left and the right. Apparently, the same artist has left similar paintings elsewhere in this area.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Site 9: Truncated painting of an eland with (probably) the white (?) colour gone. For unknown reasons, these animals were almost always polychromic. Even 2 000 km away that was the custom.

There are a few examples from the Cape and the Drakensberg where the white paint is still faintly visible explaining the bearish look of what is left of the painting. To the left there is a group of zebra/quagga, partially finely elaborated with eye and hollow ear.

This site is blocked by a huge fallen boulder that has fallen down from the roof of the shelter, apparently after the paintings were painted.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Zebra or quagga overlaying older, faint painting and a faint human figure (left) overlaying the older pictures of animals.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Site 5, new-born zebra or quagga foal, about 20 cm long.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

Site 5, the archer. The bow is part of an exact circle. Did the painter know about Euclidian geometry for the construction?

There is another example proving application of 'mathematical aesthetics' by the artists: in a remote, sensitive site, however, where the Pythagorean ratio and the ‘Golden Mean’ occurs (in one composition), certainly not by accident, as has been shown by Elizabeth Bond in Slingsby 2000, p. 51).

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

On the way back to Clanwilliam to my accommodation, I was stunned by this awesome, out-of-this-world atmosphere on the heights of the Pakhuis Pass. If I hadn’t been there in my car I would have been lost in time.

Walking the Sevilla Trail all by myself was also a ‘timeless experience’. There was hardly a sign of the modern world and the creators of the rock paintings seem to lurk behind the boulders. All photos were taken on one afternoon.

Photo: Michael Hess, April 2004

San beliefs and southern African rock art

All too often, articles on southern African rock art imply that little is known about the San (more famously known as Bushmen), hunter-gatherers who populated the whole of southern Africa for many millennia. In fact, despite widespread decimation by both black and white settlers, several San groups survive in the Kalahari Desert in Botswana and Namibia. Thanks to the work of anthropologists during the last few decades, and also to ethnographic records from the nineteenth century, we are fortunate to know much about the San way of life, complex religion and deeply religious rock art.

The central tenet of San religion was (and still is) ritualized interaction between the ‘real’ (material) and spirit worlds. The San cosmos has three levels. The spirit world—both above and below the real world—is connected to the material world by places such as waterholes (places of transformation and breakthrough) that feature prominently in San myths and beliefs. For the San, the spirit world is never far away. It impinges on daily life, and, as we shall see, this overlap of realms can be clearly seen in the rock art itself.

The most important San ritual was the healing or trance dance. These dances continue to be practised amongst San groups living in the Kalahari today. Dancers stomp in a circle around the campfire for many hours. The women clap the rhythm of the dance and sing powerful songs.

After hours of stomping, some dancers start to slip into trance or half-trance. In this altered state of consciousness many have out-of-body experiences. They describe travelling to the spirit realm..

Photo and text: http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/rari/page3.php

Movement between the material and spirit realms in the San cosmos is achieved by shamans or ‘medicine people’ . These ritual specialists are believed to have the power to alter the weather, heal the sick and to control the movements of animals. Shamans enter a state of trance (or altered state of consciousness) by intense dancing, audio-driving and hyperventilation. Unlike many other hunter-gatherer societies around the world, they do not rely on the ingestion of hallucinogens. Shamans—both male and female—harness spiritual potency by dancing around the campfire while women clap ‘medicine songs’; in this way the shamans are transported to the spirit world.

The fact that the San belief-system has lasted for many thousands of years explains why the oldest images of which we know (about 27 000 years old, in Namibia) possess elements similar to the most recent San depictions (produced about 100 years ago).

Bushmen in Deception Valley, Botswana demonstrating how to start a fire.

Photo and text: Ian Sewell

Permission: Own work, share alike, attribution required (Creative Commons CC-BY-SA-2.5)

Shamanic (or trance) dances, as well as individual elements of the dances, are depicted in the art. Human figures, for example, are often in a bending-forward posture. Today San shamans in the Kalahari say that, as potency boils in their stomachs, their muscles contract and they bend forward, often requiring the aid of one or two 'dancing sticks'. Sometimes when this happens shamans suffer nosebleeds. The San believe that the smearing of nasal blood on people keeps sickness away.

Hand-to-nose postures are also found in the art. These are probably connected with the potency of nasal blood, but they also have a greater significance: some San groups used their word for 'nose' also to mean a shaman's ability to enter trance and thus the spirit world.

Fundamentally, the art presents the shamans' privileged view of the trance dance and of the spirit world to which they are transported. This 'shaman’s eye' view explains why there are so many ‘non-real’ images in the art. In addition to spirits leaving the top of people’s heads, sickness expelled through a 'hole' in the back of a shaman’s neck, and malevolent spirits of the dead encountered in the underworld, there are also numerous depictions of therianthropes (part-human, part-animal figures), 'flying' bucks (antelope) and other unusual creatures. San art - like much hunter-gatherer rock art throughout the world - is about the 're-creation' of shamans' visions of the spirit world. In fact, the paintings were considered powerful 'things in themselves'. Inherently potent blood was often used as a binder to adhere the pigments (e.g., ochre, clay, charcoal) to the rock face.

Before the use of San ethnography, a straightforward analogy had been overlooked: The stained glass windows of European cathedrals cannot be understood without some knowledge of Christianity; similarly, San rock art cannot be understood without some insight into San beliefs.

Text above: Hampson (2002)

The Early Bushmen

The Bushmen/San were the original inhabitants of Southern Africa and are commonly known as Bushmen or San.

They were hunter-gatherers, hunting with bows and arrows, trapping small animals and eating edible roots and berries. They lived in rock shelters, in the open or in crude shelters of twigs and grass or animal skins. They made no pottery, rather using ostrich eggshells or animal parts for storing and holding liquids. For these reasons, animals and nature are central features in the Bushmen's religious tradition, folklore, art and rituals.

A San (Bushman) who gave us an exhibition of traditional dress and hunting/foraging behavior, Namibia.

Photo and text: Ian Beatty, 31 May 2006

Permission: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Because the Bushmen lived entirely of the land, they had to be nomadic. The groups, however did not wander aimlessly or relentlessly to pursue herds of antelope. Instead, they followed a carefully planned annual route that took them to different areas of plant food, as season by season, these foods ripened.

These small mobile groups comprised of up to about 25 men, women and children. Certain times of the year groups joined together for exchange of news and gifts, for marriage arrangements and for social occasions.

There are many different Bushman peoples - they have no collective name for themselves, and the terms 'Bushman', 'San', 'Basarwa' (in Botswana) are used. The term, 'bushman', came from the Dutch term, 'bossiesman', which means 'bandit' or 'outlaw'. It was given to the Bushmen during their long fight against colonial powers.

The Bushmen interpreted this as a proud and respected reference to their valiant fight for freedom from domination and colonisation. Many now accept the terms Bushmen or San. The San or Bushmen people of today are those that speak San languages.

San tribesmen from northeastern Namibia.

Photo: Benjamin Cobb, 2008

Source: http://promoteafricanews.wordpress.com/2008/11/12/a-weekend-in-bushmanland/

The principal San-speaking groups remaining today live in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia and Angola. The South African San are refugees from the Angolan and Namibian wars. Their languages, although fundamentally similar, vary considerably from place to place. San is primarily a linguistic label, adopted by anthropologists to describe people speaking these related but distinct languages.

These languages, all of which incorporate 'click' sounds are represented in writing by symbols such as !, /, //, ‡, |.

They have been oppressed and dispossessed by both Bantu and European immigrant groups. The Bushmen were regarded as not just animals, but as vermin, and history even documents hunting of them for sport.

This has lead to the total population of the Bushmen dropping to 100 000 throughout southern Africa.

Text above: http://www.theartofafrica.co.za/serv/bushmen.jsp

References

- Evans U., 1994: Hollow Rock Shelter, a Middle Stone Age site in the Cederberg, Southern African Field Archaeology, Band 3, Nr. 2, 1994, S. 63–73 (ISSN 1019-5785)

- Hampson J., 2002: Discovering Southern African rock art, Tracce, November 12, 2002

- Högberg A., Larsson L., 2011: Lithic technology and behavioural modernity: New results from the Still Bay site, Hollow Rock Shelter, Western Cape Province, South Africa, Journal of Human Evolution, Band 61, Nr. 2, 2011, S. 133–155, doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.02.006

- Slingsby P., 2000: Rock Art of the Western Cape, Book 1: The Sevilla Trail & Traveller’s rest, The FontMaker Zandvlei, South Africa (2000) ISBN 0-620-25481-5

Rock paintings from Namibia in Africa. In Namibia these rock paintings and engravings were completed by San Bushmen.

Rock paintings from Namibia in Africa. In Namibia these rock paintings and engravings were completed by San Bushmen.  Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites