Back to Don's Maps

Mammoth and Bison rock engravings in Utah

Columbian Mammoth and Bison rock engravings have been found at the Upper Sand Island rock art site at the San Juan River in Utah, USA. The engravings appear authentic, and show rock varnish and wear indicating that they are from the end of the ice age, as well as anatomical details not commonly known to the public, and accompanying motifs in a similar previously unknown style. The rock engravings date to 13 000 - 11 000 years ago.

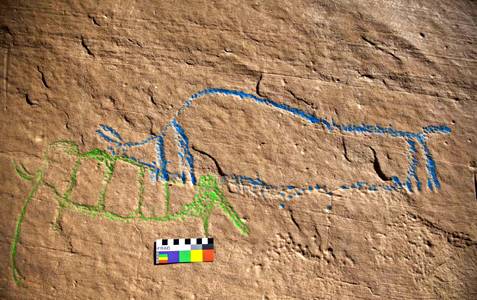

Close-up line drawing of mammoth 1 and partially superimposed bison. Width from the tips of the mammoth tusks to the end of the bison tail is 87 cm.

Artwork: © Rob Ciaccio

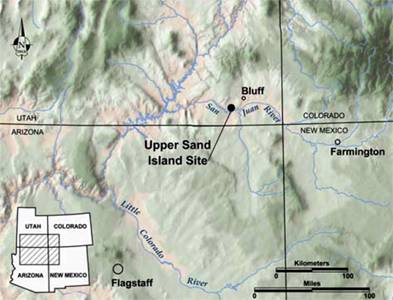

Map of the San Juan River region near Bluff,

Utah, indicating the location of the Upper Sand Island

mammoth site.

The Upper Sand Island rock art site is situated about a kilometre upstream from the well known impressive Sand Island site, and extends intermittently for several hundred metres along the vertical Navajo Sandstone cliffs bordering the flood plain of the San Juan River on its north side. Consisting exclusively of petroglyphs, the site was first recorded in 1985 by the Crow Canyon Center for Southwestern Archaeology, Cortez, Colorado (Cole, 1985) without mentioning, however, the mammoth depiction in its Figure 3.

Map: © C. Gilman

Joe Pachak, an artist from Bluff, Utah, who with the aid of the Crow Canyon report (Cole, 1985) began investigating the Upper Sand Island site on his own, introduced Ekkehart Malotki to it in the early 1990s and specifically pointed out the panel shown at left that in his eyes depicted two megafaunal genera: mammoth and bison. The art was therefore known to some archaeologists and rock art enthusiasts, but because of its difficult access — on a vertical cliff face several metres above ground level — was never scientifically investigated.

It is now believed to be a representation of a mammoth and a bison.

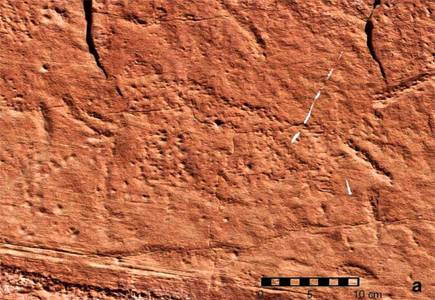

The locality is unremarkable, just another spot along the cliff face. The base of the rock exhibits only slight rock varnish, suggesting that there has been some minor erosion of the surface. The varnish on the rest of the cliff is grey, with micro-pits lacking varnish.

Photo: © H. Wallace, courtesy Ekkehart Malotki, Pers. Comm.

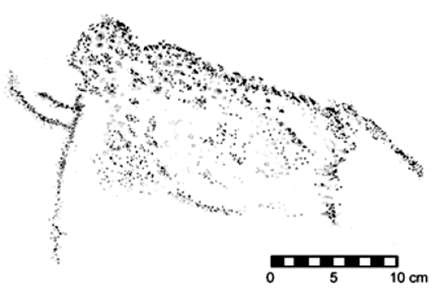

Close-up of mammoth 1's tusks and a portion of the front of the head and

start of the trunk showing continuity in patination from unmodified rock surface

to pecked portions of the design. The natural rock fissure discussed in the text is

clearly visible.

The mammoth 1 and bison are both pecked and ground. Most pecked and ground or abraded parts are revarnished with a light-grey varnish (lighter than the native rock varnish around the designs), and are notably lacking in reticulation, as seen in this close-up image.

Some pecks, especially on the lower belly line of the mammoth 1, are lighter in colour. They have no varnish, only chemical weathering. Some portions of the design follow natural microscopic fissures in the sandstone cliff face. This is the case for the front margin of the mammoth's head and the trunk, but the wide depressions seen in the trunk and front of the head, combined with some individual peck marks show that the natural fissures were exploited by the artist when creating the image.

Photo: © H. Wallace.

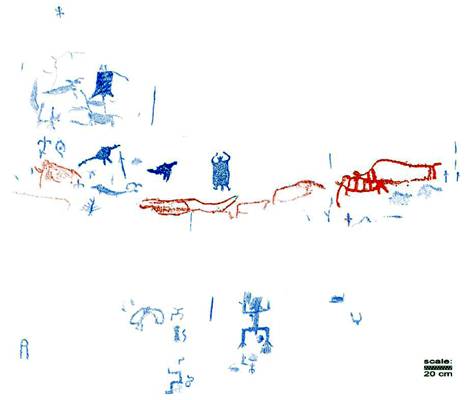

Coloured version of the mammoth/bison pecked artworks highlighted to clarify the design.

A visual examination of the incised lines by the authors using a hand lens with 5× magnification revealed no evidence for any use of metal tools or recent additions to the imagery. Instead, various degrees of varnish formation were noted. For comparison to the possible palaeo-designs, nearby horse images of Historic Ute origin located on a comparable exposure were inspected. They showed notable chemical/ mechanical weathering but no varnish formation within the pecked areas.

This lead the authors to conclude that the possible palaeo-designs are in fact significantly older than the Ute horses and are therefore not modern fakes.

Photo: © H. Wallace, Courtesy Ekkehart Malotki, Pers. Comm.

Whether one subscribes to the orthodox ‘Clovis first’ paradigm (i.e. that the earliest entrants into the New World arrived from Siberia and became the Clovis culture about 13 500 years ago), or to the now generally accepted notion that there were multiple waves of immigrants prior to Clovis, it is surprising that pictorial evidence for the co-existence of pre-Clovis people and Ice Age megamammals has not to date come to light. As is well known, the presumed ancestors of the immigrants to the Americas from the Old World had a rich tradition of image making, including rock art.

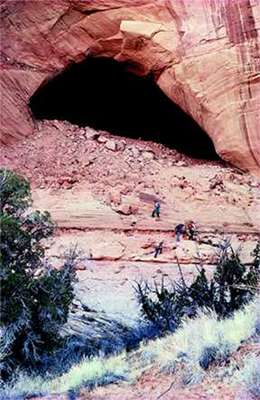

The joined megamammals, measuring 87 cm from the tips of the mammoth tusks to the end of the bison tail, are best viewed under conditions of strong side light. Their placement on the unscaleable cliff at a height of some 5 m above the remnants of an ancient gravel bar, which in turn rises an additional 7 to 8 m above the current floodplain, not only betrays the panel's deep antiquity but also renders it (hopefully) relatively safe from potential acts of vandalism.

At the time of its manufacture, presumably toward the end of the Pleistocene, the artist's access to the sandstone rock face must have been facilitated by considerably higher ground level. The San Juan River flowed at much higher levels during times of Pleistocene glaciation. As a result, outwash alluvium may have aggraded the river's valley floor by as much as 20 m, which allowed execution of the imagery at its present location.

Photo: © E. Malotki

Downcutting and lateral erosion by the river during the post-glacial Holocene subsequently removed all but a few remnants of the Pleistocene gravels, which explains the images' present-day inaccessibility. While the 'palaeoscene' constitutes the uppermost layer in the pictorial stratigraphy observed on this section of the cliff, numerous other glyphs, both amorphous and representational, populate the wall immediately adjacent or directly below it.

The joined megamammals are best viewed under conditions of strong side light. Their placement on the unscaleable cliff at a height of some 5 m above the remnants of an ancient gravel bar, which in turn rises an additional 7 to 8 m above the current floodplain, not only betrays the panel's deep antiquity but also renders it (hopefully) relatively safe from potential acts of vandalism. At the time of its manufacture, presumably toward the end of the Pleistocene, the artist's access to the sandstone rock face must have been facilitated by considerably higher ground level.

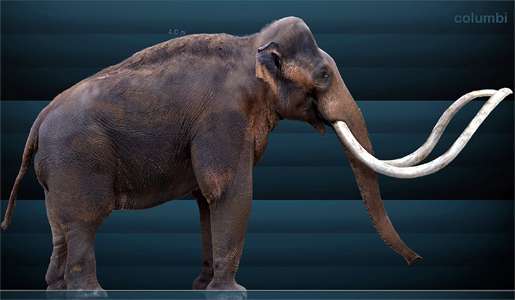

Several features unequivocally point to the portrayal of a Mammuthus columbi or Columbian mammoth. Facing left, the animal's dome-shaped head is marked by a solidly pecked top-knot, which rules out identification as a mastodon.

The eyeless head sits on a rather elongated, oval-shaped body that, compartmentalised into multiple segments, conveys a somewhat insectile impression. The two tusks, neatly aligned in parallel fashion, are relatively short and may be a sign that the artist intended to portray a young or female animal. The overlong trunk, shown in profile, may indicate that the artist was overly impressed by it. Exaggerated rendering of certain diagnostic animal parts as seen for the mammoth's trunk is a common practice in rock art iconography and is frequently seen, for example, in the portrayal of oversize paws for bears, antlers for ungulates, and tails for mountain lions in later rock art in the region.

Extending straight downward from the face of the mammoth, the trunk ends in a remarkable bifurcation that may be a portrayal of what mammalogists call ‘fingers.' As appendages of prehension, fingers of varying species-specific length and proportions served all taxa of the Order Proboscidea for picking up vegetation. This morphologic detail alone supports the authenticity of the depiction, because no modern forger or later pre-Historic Native American (assuming that tribal memory and/or oral tradition might have prompted the drawing) would be likely to have been familiar with it.

Body segmentation, as seen in the Sand Island mammoth depiction, is nearly standard in Glen Canyon linear style quadrupedal petroglyphs, where it occurs both in vertical and horizontal form. Glen Canyon linear style, generally attributed to the Middle Holocene, is amply attested at the Upper Sand Island site.

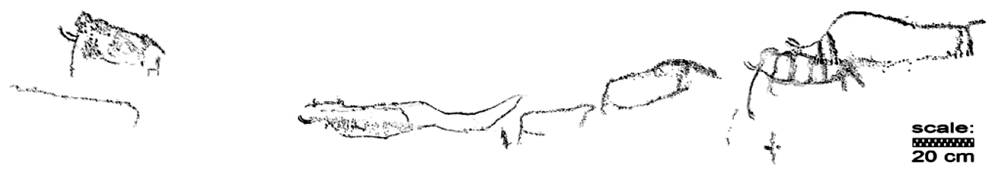

It was not until Robert Ciaccio, who drew the panel using the photographic documentation, called it to the attention of the authors that a second mammoth portrayal on the panel was recognised, in line with the row of glyphs thought to be created at roughly the same time. This drawing displays the portion of the cliff face with all designs thought to be of Pleistocene - Holocene Transition age. (i.e. the end of the last ice age.) The second mammoth is shown facing left at the far left of the row of designs.

Artwork: © R. Ciaccio

The Second Mammoth

As with mammoth 1, mammoth 2 has the distinctive dome-shaped head, small tusks and trunk, although much of the rest of the body is either weathered away or was never clearly pecked.

Artwork: © R. Ciaccio

The second mammoth also displays clearly the diagnostic traits of Mammuthus.

The design is approximately 30 cm long.

Photo: © H. Wallace.

This is a larger, detailed drawing of the entire panel of rock art, with colour coding of the ice age transition images in red, and the designs which post date them in blue, based on patination and pecking style.

Artwork: © R. Ciaccio

Dating of the site

120 km away from this site, in the Escalante River drainage of southern Utah, is Bechan Cave, where archaeological investigations uncovered over 225 cubic metres of mammoth dung, and radiocarbon dating showed that mammoths may have survived on the Colorado Plateau until about 11 000 BP. This provides a minimum age for the creation of the mammoth petroglyph at Upper Sand Island.

Bechan Cave is big enough to shelter a herd of mammoths. It is 52 metres long and 31 metres wide. Two paleontologists, Dr. Jim Mead and Dr. Larry Agenbroad, found a layer of mammoth dung from 10 centimetres to 40 centimetres deep. The scientists named it Bechan, (bay-chawn) which means 'big dung' in Navajo.

Dung from many other animals was mixed with the mammoth dung. Horses, camels, deer, ground sloths, and many other animals shared this region with the Columbian mammoths. But some whole mammoth droppings as big as bowling balls were found, and these allowed the scientists to determine that most of the dung had indeed come from mammoths. The mammoth dung had hair that matched that of wooly mammoths from Siberia, and the grass in the dung had long fibres, like that in elephant dung. The cave was used by the mammoths only occasionally, since a herd of Columbian mammoths could have dropped the amount of dung found in just a few seasons if they lived there full time.

The mammoths diet consisted of mostly grasses, as well as sedge, birch, spruce, rose, sagebrush and even cactus spines. This was a sign that they got their food from a large, dry area with a few rivers where wetland plants could grow, just like the habitat in the mountains near Bechan Cave today.

Photo: © Dr. Larry Agenbroad, The Mammoth Site

Text above: adapted from http://highlightskids.com/Science/Stories/SS0199_droppingsofmammoth.asp

A more precise time frame for the art may be deduced from archaeological evidence at the Lime Ridge Clovis site, situated a mere 12 km southwest from the Upper Sand Island rock art location.

The site, characterised as a hunting stand, yielded some 300 stone artefacts, including six Clovis projectile point fragments. Davis (1994) conjectures that the site was selected because riparian corridors in the area may have attracted large mammals in the otherwise arid landscape of the Late Pleistocene. No dates are available for the site. However, on the basis of chronometric reassessments of existing Clovis sites, as well as newly obtained radiocarbon ages, the Clovis palaeocomplex is now more accurately dated by Goebel et al (2008) to a temporal niche of a mere 300 years between 13 200–13 100 to 12 900–12 800 years ago.

With this temporal window serving as a possible maximum age, and provided that the mammoth panel was not made by pre-Clovis foragers, we can assume that it was most likely cut in the rock some time between 13 000 and 11 000 calendar years ago.

Thus, it can be confidently stated that, when we consider the Vero Beach, FL carving of a mammoth, as well as these rock wall art images, humans and now-extinct megamammals shared the same North American landscape at the end of the last Ice Age. Furthermore, given that they were not pecked in isolation, there is the implication that other rock art dating to this era is likely present in the area.

The Columbian Mammoth, Mammuthus columbi, was one of the largest of the mammoth species and also one of the largest elephants to have ever lived, measuring 4 metres (13 ft) tall and weighing up to 10 000 kilograms. It was 10.7 feet (3.3 m) long at the shoulder, and had a head that accounted for 12 to 25 percent of its body weight. It had impressive, spiralled tusks which typically extended to 6.5 feet (2.0 m). A pair of Columbian Mammoth tusks discovered in central Texas was the largest ever found for any member of the elephant family: 16 feet (4.9 m) long.

It was a herbivore, with a diet consisting of varied plant life ranging from grasses to conifers. It is also theorised that the Columbian Mammoth ate the giant fruits of North America such as the Osage orange, Kentucky coffee and Honey locust as there was no other large herbivore in North America then that could eat these fruits.

Using studies of African elephants, it has been estimated that a large male would have eaten approximately 700 pounds (320 kg) of plant material daily. The average Columbian mammoth ate 300 pounds of vegetation a day.

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

Photo: Sergiodlarosa

Date: 2008-11-05

Permission: GNU Free Documentation License

References

- Cole, S., 1985: San Juan River rock art expedition sponsored by Crow Canyon Center for Southwestern Archaeology Cortez, Colorado, 6 pp. text, 28 pp. photocopied b/w photos and drawings. Edge of Cedars Museum, Blanding, UT.

- Davis, W., 1994: The first Americans in San Juan County. Blue Mountain Shadows 13: 4–6.

- Goebel, T., Waters, M., O'Rourke D., 2008: The late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas. Science 319: 1497–1502.

- Malotki, E. and Wallace H., 2011: Columbian Mammoth Petroglyphs from the San Juan River near Bluff, Utah, United States. Rock Art Research 2011 - Volume 28, Number 2, pp. 143-152.