Back to Don's Maps

Did Megafauna die from hunting or climate change?

Although most scientists with knowledge of the field think that the Australian megafauna, animals such as the giant kangaroo, the swamp cow and the diprotodon, were hunted to death by the first humans to migrate to Australia, perhaps 50 000 years ago. However some scientists still disagree, and put forward the hypothesis that climate change was to blame.

The main reason cited for rejecting overkill is that there is no direct evidence that people killed the megafauna. There are no huge piles of bones near ancient campsites, there are no giant kangaroo skeletons with spears in their ribs, and no evidence of specialised weapons for bringing down large prey. Few sites have remains of people and megafauna in close association - though that might be the case at Lake Mungo, where evidence for megafauna and people is at least found at the same spot.

Thus some archaeologists conclude that megafauna-hunting just did not happen, or if it happened it was rare and insignificant.

However a crucial question must be asked: if people did hunt megafauna to extinction, how much evidence of killing should we now be able to get from archaeological sites? A new paper by archaeologists Todd Surovell and Brigid Grund, Surovell et al. (2012), suggests the answer to that question is 'very little or none'.

As Christopher Johnson, Professor of Wildlife Conservation and ARC Australian Professorial Fellow at University of Tasmania notes:

Surovell and Grund point out, first, that the period when archaeological evidence of killing of megafauna could have been formed is a small fraction of the total archaeological record of Australia. People arrived here between about 50 000 and 40 000 years ago. This is also the interval during which animals like diprotodon disappeared. A comparison of archaeological and fossil dates suggests humans and megafauna overlapped for only about 4 000 years continent-wide, and modelling suggests that if hunting caused extinction it would have been all over in less than 1 000 years in any place.Text above from: http://theconversation.edu.au/hunting-or-climate-change-megafauna-extinction-debate-narrows-10602

This means that no more than 8%, perhaps as little as 2%, of the Australian archaeological record covers the period of human-megafauna interaction. The 'smoking gun' evidence of overkill should therefore be rare. Surovell and Grund show that the problem of finding such evidence is even worse than that, for two reasons.

First, when people first arrived their populations were necessarily small. Living sites therefore occurred at low density. As population size grew exponentially, site density increased. So, the very earliest sites must be far rarer than later ones.

But if overkill happened, populations of megafauna would have been going down as humans went up: as the density of sites was rising the proportion of them that could have contained evidence of megafauna kills was falling. Thus, sites with potential to preserve that evidence are actually a tiny proportion, perhaps much less than .01%, of the total archaeological record.

Second, material in archaeological sites degrades with time due to breakdown, weathering and scavenging of bone and removal by erosion. Old sites are eventually buried under sediments. The probability of discovering archaeological sites from the earliest occupation of Australia is intrinsically much lower than for later times, and most of the contents of those sites will have disappeared.

In fact, the very oldest archaeological sites in Australia typically contain only a few stone tools. They can tell us very little about interaction of the first Australians with any animals or plants, let alone reveal a picture of megafauna-killing.

Our fundamental task as scientists is to test hypotheses using evidence. To test the overkill hypothesis, we need a kind of evidence that would differ according to whether the hypothesis is true or false. Obviously, if overkill did not happen, evidence of megafauna-killing should be rare in the archaeological record. But, Surovell and Grund’s analysis makes it clear that if overkill happened, we should still expect evidence of killing to be rare. Therefore, failure to find such evidence does not amount to a test of the overkill hypothesis.

This does not mean that archaeological evidence of killing (or absence of such evidence) is useless in testing the overkill hypothesis. Surovell and Grund show it can be useful, by comparing the archaeological records of Australia, North America and New Zealand. All three places lost their megafaunas when people arrived, but this happened a very long time ago in Australia, and very recently (700 years ago) in New Zealand. North America is intermediate, with human arrival and extinction from 14 000 to 13 000 years ago.

Applying the same logic to all three cases, we predict that if overkill caused megafaunal extinction in each place the archaeological evidence of killing should be abundant in New Zealand, rare in North America, and vanishingly rare in Australia. That is exactly what we find.

There is so much evidence showing New Zealand’s moa were heavily hunted that nobody doubts overkill was the main cause of their extinction. In North America, there are undoubted kill sites for mammoths, mastodons and a few other species, but this evidence is far thinner than in New Zealand. Australian archaeology is yet to reveal any convincing evidence for megafauna-killing.

So, far from disproving overkill, the archaeological evidence from Australia is actually consistent with the overkill hypothesis.

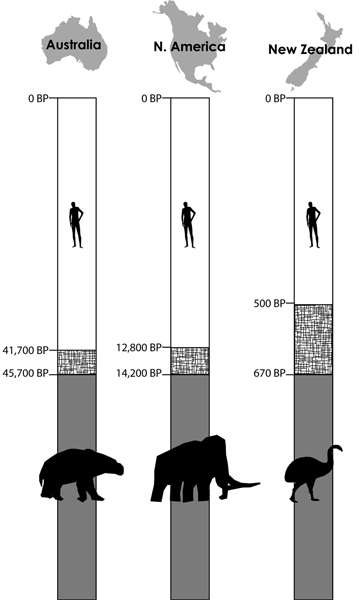

Relative coexistence of humans and megafauna in Australia, North America, and New Zealand.

Gray bars indicate the presence of extinct fauna. White bars indicate the presence of humans. Hatched bars indicate periods of coexistence of both humans and extinct fauna.

(Note that according to this graph the period of coexistence was 4 000 years in Australia, 1 400 years in North America, and just 170 years in New Zealand - Don )

Photo and text: Surovell et al. (2012)

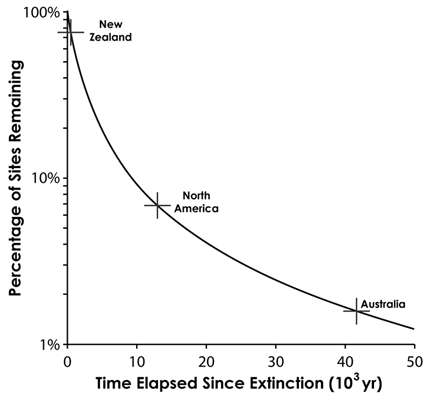

The estimated percentage of archaeological sites remaining of all that were created at the time of faunal extinction based on the model of taphonomic bias developed in Surovell et al. (2009). Crosses indicate the positions of estimated extinction dates and percentage of sites remaining for New Zealand, North America, and Australia.

Photo and text: Surovell et al. (2012)

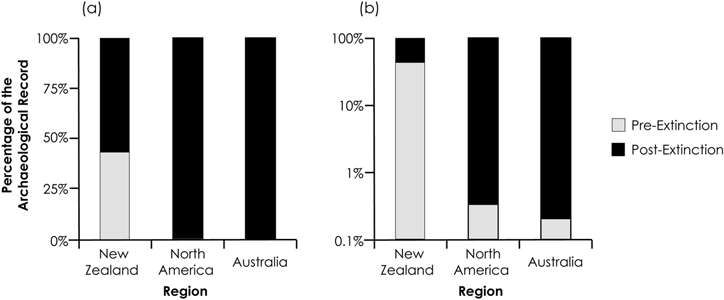

The percentage of archaeological radiocarbon dates from New Zealand, North America, and Australia pre- and

post- dating faunal extinction.

(

On the left is a graph with a linear time scale on the Y axis. Here we can see that there is about 40% of archaeological radiocarbon dates before the extinction event for New Zealand, but negligible, unplottable values for North America and Australia.

On the right a logarithmic scale has been used, with tick marks at 0.1%, 1%, 10% and 100%, in order to display useful information - Don )

Photo and text: Surovell et al. (2012)

Australian Megafauna

Australian Megafauna

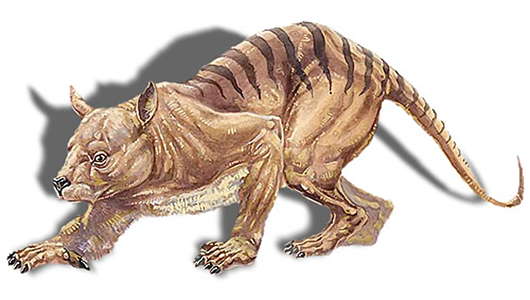

A recreation of the Marsupial Lion, Thylacoleo carnifex

Photo: OZ fossils, via http://www.abc.net.au/science/games/quizzes/2009/megafauna/

Australian Megafauna

A recreation of the Marsupial Lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, at the Naracoorte Caves display.

Display: Naracoorte Caves, South Australia

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

Marsupial Lion

Display: Naracoorte Caves, South Australia

Source: Facsimile

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

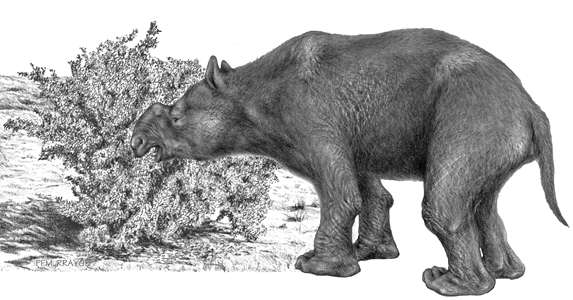

An extinct marsupial mega-herbivore, Diprotodon optatum.

Photo: Art Peter Murray, image © Science/AAAS

Australian Megafauna

Diprotodon, meaning 'two forward teeth', sometimes known as the giant wombat or the rhinoceros wombat, is the largest known marsupial ever to have lived. Along with many other members of a group of unusual species collectively called the 'Australian megafauna', it existed from approximately 1.6 million years ago until extinction some 46 000 years ago(through most of the Pleistocene epoch).

Diprotodon species fossils have been found in sites across mainland Australia, including complete skulls and skeletons, as well as hair and foot impressions. Female skeletons have been found with babies located where the mother's pouch would have been. The largest specimens were hippopotamus-sized: about 3 metres (10 ft) from nose to tail, standing 2 metres (6.6 ft) tall at the shoulder and weighing up to 2 800 kilograms (6 200 lb). They inhabited open forest, woodlands, and grasslands, possibly staying close to water, and eating leaves, shrubs, and some grasses.

The closest surviving relatives of Diprotodon are the wombats and the koala. It is suggested that diprotodonts may have been an inspiration for the legends of the bunyip, as some Aboriginal tribes identify Diprotodon bones as those of 'bunyips'.

Text above: Wikipedia

Photo: http://sydkab.wordpress.com/tag/thylacoleo/

Australian Megafauna

Diprotodon optatum

Display: NPWS centre, Lake Mungo NP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

Diprotodon australis lower molar.

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Source: Original, or museum quality facsimile

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

Diprotodon australis incisors.

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Source: Original, or museum quality facsimile

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

Diprotodon australis

The Diprotodon consumed about 150 Kilograms of browse (leaves, reeds and shrubs) per day. They therefore produced 36.5 tonnes of manure per year!

Display and text: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Painter: Nicholas Pike, 2002

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

Diprotodon australis

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Painter: Nicholas Pike, 2002

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

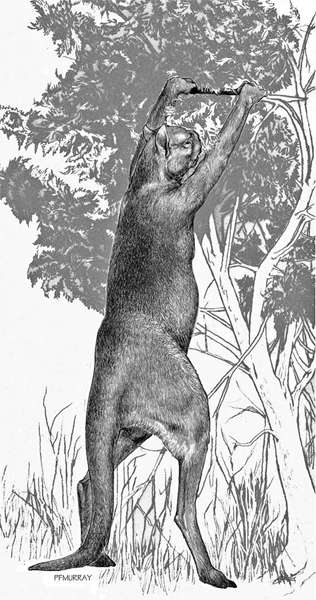

Sthenurus, an extinct browsing kangaroo.

Sthenurus ('Strong Tail') is an extinct genus of kangaroo. With a length of about 3 m (10 ft), some species were twice as large as modern extant species. Sthenurus was related to the better-known Procoptodon.

Photo: Art Peter Murray, image © Science/AAAS

Australian Megafauna

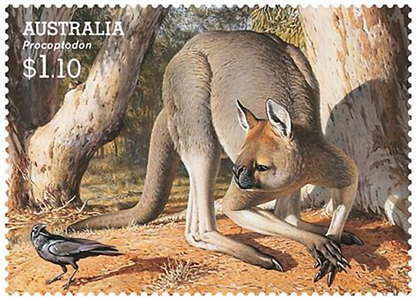

Procoptodon goliah, an extinct browsing kangaroo, and the largest, which was only two metres tall but weighed more than 200 kg.

Photo: Australia Post, via http://www.smh.com.au/

Australian Megafauna

The Giant Kangaroo was a browser of leaves from trees and shrubs. It consumed a large amount of plant material each day.

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Painter: Nicholas Pike, 2002

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

Giant Kangaroo Jaw and rib.

Display: Lake Mungo NP NSW

Source: Original

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

The Swamp cow Zygomaturus trilobus

Zygomaturus trilobus had a size and build similar to a pygmy hippopotamus, weighing around 300 to 500 kg.

The scientific name refers to the broad zygomatic arches (cheek bones) and the three prominent lobes of the premolar teeth.

Some of the features of its skeleton suggest it may have preferred swampy habitats.

It possibly lived in small herds around the wetter, coastal margins of Australia and occasionally may have extended its range along the watercourses into central Australia.

A ground dweller, it moved on all four limbs.

Text: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/sanpr/naracoortecaves/ea8.html

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Painter: Nicholas Pike, 2002

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

Jaw of the Swamp cow Zygomaturus trilobus

Zygomaturus is an extinct giant marsupial from Australia during the Pleistocene. It had a heavy body and thick legs and is believed to be similar to the modern Pygmy Hippopotamus in both size and build. The genus moved on all fours. It lived in the wet coastal margins of Australia and became extinct about 45,000 years ago.

Zygomaturus also is believed to have expanded its range toward the interior of the continent along the waterways. It is believed to have lived solitarily or possibly in small herds. Zygomaturus probably ate reeds and sedges by shovelling them up in clumps with its lower incisor teeth.

It was a large sized animal, weighing 500 kg (1100 lbs) or more and standing about 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall and 2.5 m (8.2 ft) long.

Display: Lake Mungo NP NSW

Text: Wikipedia

Source: Original

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Digging at Black Swamp, Kangaroo Island, 1996. This dig exposed the fossils of the swamp cow, Zygomaturus trilobus.

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Photo of the display: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

The skull of the swamp cow, Zygomaturus trilobus found at Black Swamp.

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Photo of the display: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

The skull of the swamp cow, Zygomaturus trilobus found at Black Swamp.

Display: Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island

Source: Probably original.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna

A recreation of the swamp cow, Zygomaturus trilobus at the Naracoorte Caves display.

Display: Naracoorte Caves, South Australia

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2009

Australian Megafauna marsupials that became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene:

Diprotodon optatum

D. minor

Euryzygoma dunense

Euwenia grota

Lasiorhinus angustioens

Macropus ferragus

M. pearsoni

M. piltonensis

M. roma

M. Thor

Nototherium mitchelli

Palorchestes azeal

P. parvus

Phascolonus gigas

Phascolomys medius

Procoptodon goliah

P. pusio

P. rapha

P. texasensis

Propleopus oscillans

Protemnodon anak

P. brehus

P. roechus

Ramsayia magna

Simosthenurus brownei

S. gilli

S. maddocki

S. occidentalis

S. orientalis

S. pales

Sthenurus andersoni

S. atlas

S. oreas

S. tindalei

Troposodon minor

Thylacoleo carnifex

Vombatus hacketti

Warendja wakefieldi

Zaglossus hacketti

Z. ramsayi

Source for the list of extinct megafauna above: http://www.austhrutime.com/marsupial_megafauna.htm

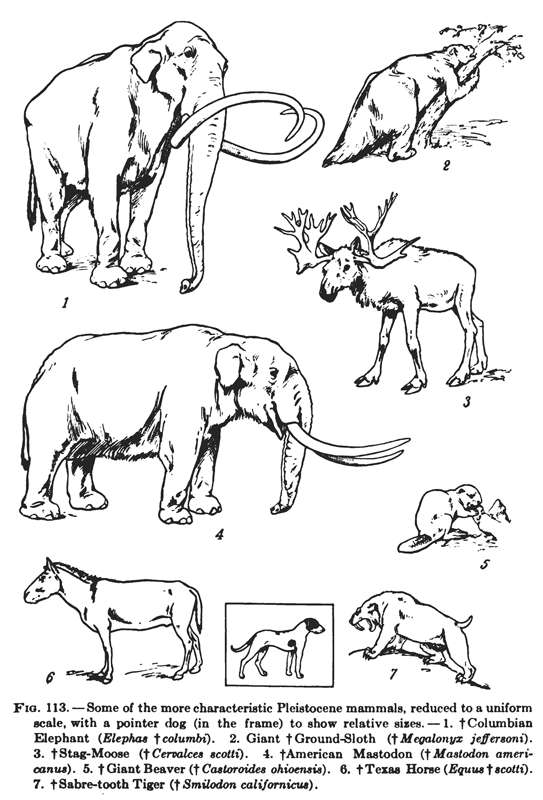

North American Megafauna

Some of the more characteristic Pleistocene mammals, reduced to a uniform scale, with a pointer dog (in the frame) to show relative sizes.

1. ✞ Columbian Elephant (Mammuthus columbi)

2. ✞ Giant Ground-Sloth (Meqalonyx jeffersoni)

3. ✞Stag-Moose (Cervalces scotti)

4. ✞American Mastodon (Mammut americanum)

5. ✞Giant Beaver (Castoroides ohioensis)

6. ✞Texas Horse (Equus scotti).

7. ✞Sabre-tooth Tiger (Smilodon californicus)

Photo: Scott (1913)

Pleistocene fauna in the Americas included giant sloths; short faced bears; several species of tapirs; peccaries (Including the long nosed and flat-headed peccaries); the American lion; giant condors; Miracinonyx ('American cheetahs', not true cheetahs); saber-toothed cats like Smilodon and the scimitar cat, Homotherium; dire wolves; saiga; camelids such as two species of now extinct llamas and Camelops; at least two species of bison; stag-moose; the shrub-ox and Harlan's muskox; horses; mammoths and mastodons; and giant beavers as well as birds like teratorns and giant tortoises. The nine-foot sabertooth salmon lived at the time as well. In contrast, today the largest North American land animal is the American bison.

Text above from Wikipedia

The American Mastodon, Mammut americanum

Photo: Sergiodlarosa, GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or later

The genus Mastodon, (from the Greek Mastos, meaning breast, and odon: tooth, referring to the the nipple-shaped protrusions on the crowns of its molars) belongs to the family Mammutidae, which is a family within the mammal order Proboscidea. Although Mastodons share their ancestor, Palaeomastodon, with the elephants and mammoths they remain a side line of their own.

7 million years ago the Mastodons spread to north America, and later to south America. The mastodons were about the same size as the elephants and the mammoths, but more muscled, and most species had fur. The upper jaw had two big tusks, the lower jaw had two smaller tusks. Mastodons had never more than two molars in the jaw at the same time.

Text above from: http://www.elephant.se/mastodon.php?open=Evolution%20of%20elephants

North American Megafauna

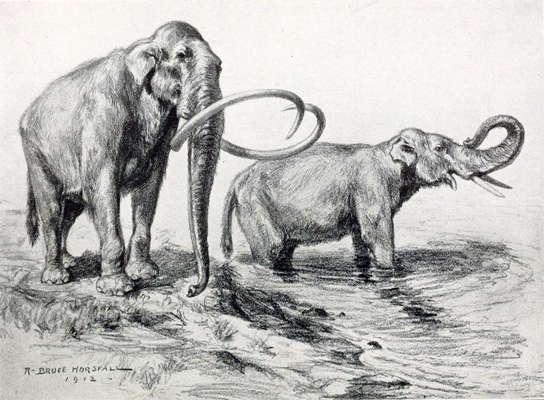

Columbian Mammoth, Mammuthus columbi

Photo: Robert Bruce Horsfall

Permission: Public Domain

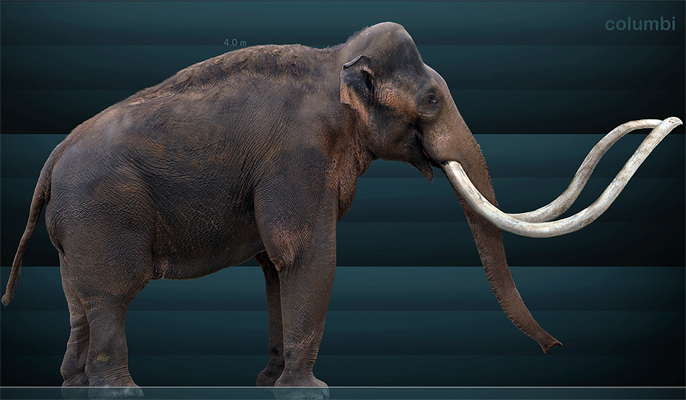

North American Megafauna

Columbian Mammoth, Mammuthus columbi

(Note that this reconstruction has been criticised for looking too much like an asian elephant - it is hairless, which may not have been the case. However, it is interesting in that the basic shape and even details of the animal are almost identical to the hairy mammoth of Europe and Asia - Don )

Photo: http://dinooftheweek.blogspot.com.au/2011/10/real-question.html

North American Megafauna

Stag Moose, Cervalces scotti

(Moose always seem a little sad to me, I've seen them in the wild feeding in a swamp, and this one is no exception. Life seems to have treated them badly. They were somehow shortchanged in the evolutionary roulette wheel, and they seem to me a little like Eeyore, from the Pooh Bear series - Don )

Photo: Robert Bruce Horsfall

Permission: Public Domain

North American Megafauna

Stag Moose, Cervalces scotti

Photo: http://dantheman9758.deviantart.com/art/Cervalces-scotti-197830053

North American Megafauna

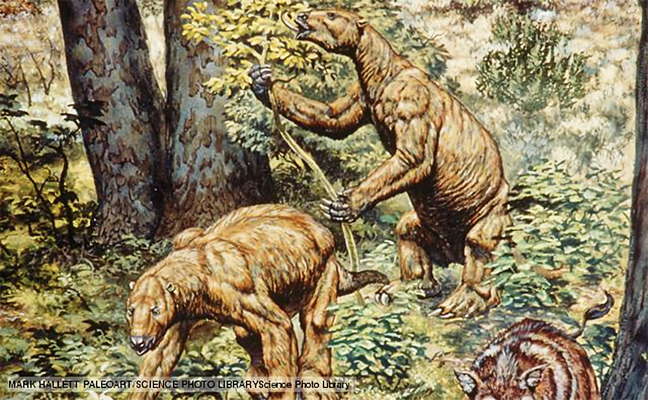

Giant Ground Sloth, Megatherium americanum

Although related to modern tree sloths, giant ground sloths resembled no other animal: they lived on the ground, rivalled the mammoths in size and were some of the strangest mammals ever. Their remarkable claws were up to 50cm long, the size of a man's forearm. Massive hind quarters gave way to much slimmer shoulders and a tiny head. Originally from South America - fossils have been found in Argentina - giant ground sloths spread north to the southern part of North America. Slight differences in fossils from South America suggest that males and females may have differed in size and/or appearance, which hints at a gender-based social structure.

Photo: © Mark Hallett Paleoart/Science Photo Library Science Photo Library

Text: http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/life/Megatheriidae

North American Megafauna

Short Faced Bear

Scientific name: Arctodus simus

The short-faced bear or bulldog bear, or Arctodus (Greek, 'bear tooth'), is an extinct genus of bear endemic to North America during the Pleistocene ~3.0 Ma. – 11 000 years ago, existing for approximately three million years. Arctodus simus may have once been Earth's largest mammalian, terrestrial carnivore. The species described are all thought to have been larger than any living species of bear. It was the most common of early North American bears, being most abundant in California.

Photo: Sergiodlarosa

Permission: licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Text: Wikipedia

North American Megafauna

Tapir

Dennis Avery, along with artist Ricardo Breceda, decided to bring back to Galleta Meadows, in the California desert, an extinct animal called Tapirus merriami, or Merriam's tapir, an ungulate that roamed these parts about a million years ago. Take a look at the illustration showing Merriam's tapir as it might have looked on the shores of Lake Borrego so far back in time.

Photo: © Pat Tillet

Text: http://tapirgallery.blogspot.com.au/

North American Megafauna

Giant Bison, Bison latifrons

Bison latifrons reached a shoulder height of 2.5 meters (8.2 ft) and weighed over 2 000 kilograms (4 400 lb). It competes with the 'giant Africa buffalo' Pelorovis for the title a the largest bovid that ever lived. The horns of Bison latifrons measured as great as 213 centimetres (84 in) from tip to tip, compared with only 66 centimetres (26 in) in modern Bison bison.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2012

Source: Regina Museum, Saskatchewan, Canada

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

North American Megafauna

Giant Bison, Bison latifrons

This bison apparently didn't congregate in the giant herds of modern bison, preferring to roam the plains and woodlands in smaller family units.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2012

Source: Regina Museum, Saskatchewan, Canada

Text: Adapted from http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/mesozoicmammals/p/Bison-Latifrons.htm

North American Megafauna

Giant Bison, Bison latifrons

The known dimensions of the species are much larger than any extant bovid, including both extant species of bison — the American bison and the European bison. Based on a comparison of limb bones between Bison latifrons and Bison bison, the mass of the former is estimated to have been 25%–50% greater than that of the latter. In fact, Bison latifrons is possibly the largest bovid in the fossil record.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2012

Source: Regina Museum, Saskatchewan, Canada

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

North American Megafauna

Giant Bison, Bison latifrons Vertebra with Atlatl point embedded in it, on exhibit at the Maidu Interpretive Center.

Cherokee, Oklahoma 6 000 - 5 500 BP

Photo: Justin Smith

Permission: © Justin Smith / Wikimedia Commons, CC-By-SA-3.0, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

North American Megafauna

Giant Pleistocene Beaver, Castoroides ohioensis

The giant beaver looked similar to modern beavers but, as the name implies, was considerably larger: it grew over 8 ft (2.4 m) in length - making it not only the largest rodent in North America during the last ice age but also the largest known beaver - and weighed roughly 60 to 100 kg (130 to 220 lb) - the size of a modern black bear.

Its hind feet were much larger than in modern beavers, but, because soft tissues decay, it is not known whether its tail resembled the tails in modern beavers and, similarly, it can only be assumed that its feet were webbed like in modern species.

The incisors were 15 cm (5.9 in) long, and had blunt, rounded tips, in contrast to the chisel-like tips found in modern beaver cutting teeth. The molars were well adapted to grinding and resembled those of capybaras with an S-shaped pattern on the grinding surfaces.

Photo: Ryan Somma

Permission: Creative Commons Licensed photo by ideonexus.com.

Source: Taken at the Minnesota Science Museum: Mississippi River Gallery.

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

North American Megafauna

Giant Pleistocene Beaver, Castoroides ohioensis, skeleton

One of the important anatomical differences between the giant beaver and modern beaver species, besides size, is the structure of their teeth. Modern beavers have chisel-like incisor teeth for gnawing on wood. The teeth of the giant beaver are bigger and broader, and grew to about 15 centimetres (6 inches) long. In addition, the tail of the giant beaver must have been longer but narrower, and its hind legs shorter. Its great bulk might have restricted its movement on land (although large squat-legged hippopotamuses can move on land with little difficulty).

Castoroides ohioensis had a length of up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) and an estimated weight of 60-100 kg (130-220 lbs); past estimates went up to 220 kg (485 lbs). It lived in North America during the Pleistocene epoch and went extinct at the end of the last Ice Age, 12 000 years ago.

Photo: C. Horwitz

Permission: licensed under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2, and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Source: Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois in August 2006

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

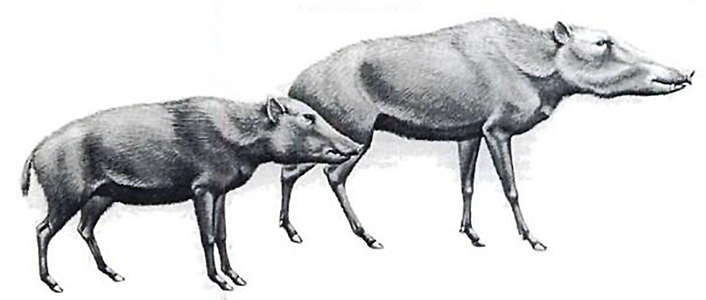

North American Megafauna

Restoration of the extinct long nosed peccary, Mylohyus nasutus (right) and the flat-headed peccary, Platygonus compressus (left).

Photo: Drawn by C.L. Ripper, in Prothero et al. (2003)

North American Megafauna

Long nosed peccary, Mylohyus nasutus

Photo: ©Reynosa Blogs from Reynosa Tamaulipas, Mexico, photographed at Austin Zoo, Texas USA, 2009

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

North American Megafauna

Sabre tooth cat, Smilodon populator

According to http://library.sandiegozoo.org/factsheets/_extinct/smilodon/smilodon.htm there were three species of Smilodon existed between 2.5 million and 13 000 years ago

Smilodon gracilis smallest and earliest. Found mainly in eastern North America

Smilodon populator: largest, about the size of modern lions. Found in South America

Smilodon fatalis intermediate in size. Found in North America and Pacific coastal areas of South America

Smilodon fatalis became extinct about 13 000 years ago.

To this we can add Smilodon californicus, famously from the La Brea Tar Pits. Smilodon californicus is the second most common fossil at La Brea, behind the dire wolf. Literally hundreds of thousands of its bones have been found, representing thousands of individuals. It was first described by Professor John C. Merriam and his student Chester Stock in 1932. Today, it is the California state fossil. But Smilodon californicus was not restricted to California; it ranged over much of North and South America.

Photo: Charles R. Knight, 1905, from the American Museum of Natural History

Permission: Public Domain>

Text: http://library.sandiegozoo.org/factsheets/_extinct/smilodon/smilodon.htm and http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/quaternary/labrea.html

North American Megafauna

Sabre tooth cat, Smilodon californicus takes down its prey at the La Brea Tar Pits.

Photo: fatedsnowfox

Permission:Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Source: Page Museum, La Brea Tar Pits, Los Angeles

North American Megafauna

Dire Wolf, Canis dirus

The dire wolf (Canis dirus 'fearsome dog') is an extinct carnivorous mammal related to the smaller extant grey wolf. It was most common in North America and South America from the Irvingtonian stage to the Rancholabrean stage of the Pleistocene epoch, living 1.80 million years ago to 10 000 years ago, persisting for approximately 1.79 million years.

The dire wolf averaged about 1.5 meters (5 ft) in length and weighed between 50 kg (110 lb) and 79 kg (174 lb). With the exception of the canine teeth in some populations, male and female body and teeth sizes evidence no major differences. In some populations, males' canines were considerably larger, implying male competition for breeding access. In other populations, lack of sexual dimorphism in the canine teeth implies little competition.

Despite superficial similarities to the grey wolf, the two species differed significantly. Today's largest gray wolves would have been of similar size to an average dire wolf; the largest dire wolves would have been considerably larger than any modern grey wolf. The dire wolf is calculated to weigh 25% more than living grey wolves. Much of these characteristics were needed in order to fight off and prey on large megafauna. The legs of the dire wolf were proportionally shorter and sturdier than those of the grey wolf, and its brain case was smaller than that of a similarly sized grey wolf.

Photo: http://www.scientificlib.com/en/Biology/Animalia/Chordata/Mammalia/CanisDirus01.html

Text: Wikipedia

North American Megafauna

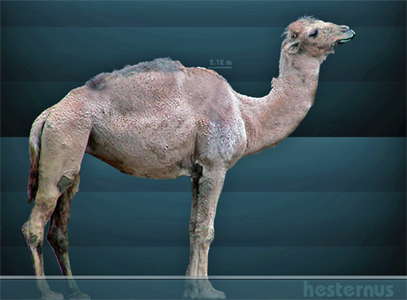

Camel, Camelops hesternus,

Camelops is an extinct genus of camels that once roamed western North America, where it disappeared at the end of the Pleistocene about 10 000 years ago.

The genus Camelops first appeared during the Late Pliocene period and became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. The family Camelidae, which comprises camels and llamas, originated from North America. Despite the fact that camels are presently associated with the deserts of Asia and Africa, Camelidae originated from North America during the middle Eocene period, at least 44 million years ago.

The camel and horse family originated in the Americas and migrated into Asia via the Beringian strait.

During the late Oligocene and early Miocene periods, camels underwent swift evolutionary change, resulting in several genera with different anatomical structures, ranging from those with short limbs, those with gazelle-like bodies, and giraffe-like camels with long legs and long necks. Unfortunately, this rich diversity decreased until only a few species, such as Camelops hesternus, remained in North America, before going extinct entirely around 11 000 years ago. Camelops' extinction was part of a larger North American die-off in which native horses, camelids and mastodons also died out. This megafaunal extinction coincided roughly with the appearance of the big game hunting Clovis culture, and biochemical analyses have shown that Clovis tools were used in butchering camels.

Because soft tissues are generally not preserved in the fossil record, it is not certain if Camelops possessed a hump, like modern camels, or lacked one, like its modern llama relatives. Camelops hesternus was seven feet (slightly over two metres) at the shoulder, making it slightly taller than modern Bactrian camels. It was slightly heavier also, weighing typically around 800 kg (1 800 lb) with large specimens up to around 1 200 kg (2 600 lb). Plant remains found in its teeth exhibit little grass, suggesting that the camel was an opportunistic herbivore; that is, it ate any plants that were available, as do modern camels. Studies on the Rancho la Brea Camelops hesternusfossils further reveal that rather than being limited to grazing, this species likely ate mixed species of plants, including coarse shrubs growing in coastal southern California. Camelops probably could travel long distances, similar to the living camel. The ability to exist for long periods without water, such as modern-day camels, is still unknown; this may have been an adaptation that occurred much later, after camelids migrated to Asia and Africa.

Photo: Sergiodlarosa

Permission: licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

North American Megafauna

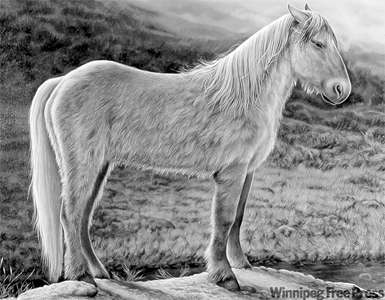

Horse, Equus lambei

The long-frozen remains of an extinct ice age horse, dug up in 1993 by gold miners in the Klondike, have finally been put on public display at a Yukon museum after giving scientists a new picture of what the long-gone species looked like when it roamed the Canadian North with woolly mammoths 26 000 years ago.

Exquisitely preserved in ancient permafrost, the horse's partial carcass -- including a foreleg, hide, mane and tail -- is being described by Yukon officials as a national treasure and the finest intact specimen of "a mummified, extinct large mammal ever found in Canada.'

At an unveiling last month in Whitehorse -- the aptly named new home of the light-coloured, pony-sized Equus lambei-- Yukon Culture Minister Elaine Taylor hailed the specimen as a unique centrepiece for the city's Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre.

The museum is dedicated to exploring the prehistoric grassland ecosystem that existed until about 10 000 years ago in a glacier-free zone covering present-day Siberia, Alaska and Yukon.

'The Yukon Horse exhibit adds an important piece of Beringia history to an already impressive list of recent scientific discoveries in the Yukon,' Taylor said.

'We are proud of the work done to date to learn from this wonderful artifact and the collaboration among industry, governments and the scientific world, which is helping to ensure special discoveries like the Yukon horse are preserved and shared for today and future generations'

When the horse was discovered 16 years ago near Last Chance Creek by miners Sam and Lee Olynyk and Ron Toews, the powerful stench led experts to suspect a dead pack mule from the days of the Klondike gold rush had melted out from a century-long deep-freeze.

Instead, analysis showed the animal lived about 14 millennia before humans ever set foot in North America -- a time when ice age horses, camels, steppe bison, scimitar cats and mammoths roamed the far northwest's ice-free grassland.

The horse found by the miners -- its flesh, hair and bones still in a remarkable state of preservation -- apparently had become stuck in mud and set upon by wolves before or after death.

When the carcass was shipped to Ottawa in 1993 to be studied and preserved by experts from the Canadian Museum of Nature and the Canadian Conservation Institute, a predator's teeth marks were found on the animal's remains.

Years of research on the beast 'substantially changed the scientific view about the Yukon horse,' said a Yukon government statement.

'The hide showed that the animal looked something like Przewalski's horse, which still survives today in Mongolia.'

Dick Harington, a top Canadian paleontologist who led the Ottawa analysis, praised the miners 'for their magnificent co-operation with scientists in helping to establish our knowledge of this important, now extinct, species.'

Grant Zazula, the Yukon government scientist who helped arrange the horse's long-awaited return to the territory, said researchers refined their understanding of the light-blond colouring and short, stubby-haired coat of Equus lambei.

'It's not too often you get a chance to see a big chunk of a 26 000-year-old animal,' he said. 'It's great that it's finally on display.'

This month, a study of the Klondike's many paleontological treasures -- co-authored by Zazula and six other Canadian and British researchers -- was published in the international geological journal GSA Today.

The study highlighted the rich scientific legacy of the Klondike gold rush, when miners digging for riches frequently exposed important geological features and rare ice age specimens such as mammoth bones and ancient, fossilised squirrel nests.

Photo and text: http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/yukon-museum-exhibits-remains-of-extinct-horse-54281122.html

North American Megafauna

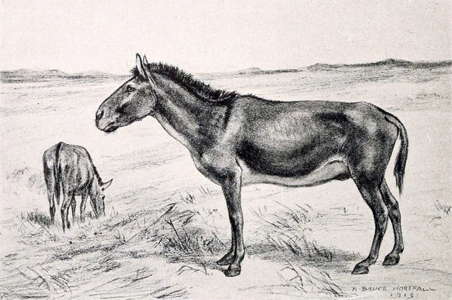

Horse, Equus scotti

Equus scotti, named after vertebrate paleontologist William Berryman Scott, is an extinct species of Equus, the genus that includes the horse. Equus scottii was native to North America and likely evolved from earlier, more zebra-like North American equids early in the Pleistocene Epoch. The species may have crossed from North America to Eurasia over the Bering land bridge during the Pleistocene. The species died out at the end of the last ice age in the large-scale Pleistocene extinction of megafauna.

It was among the last of the native horse species in the Americas until the reintroduction of the horse approximately 10 000 years later, when conquistadors brought modern horses to North and South America ca 16th century, some of which later escaped to the wild and became ancestors of the many feral horses living today in the Americas.

The species was named from Rock Creek, Texas, United States, where multiple skeletons were recovered.

Photo: Robert Bruce Horsfall

Permission: Public Domain

Source: Scott (1913)

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

North American Megafauna

The Shrub Ox, Euceratherium collinum, (? formerly Preptoceras sinclairi ?) is an extinct genus and species of Bovidae native to North America. It is a close relative of the musk-ox.

Euceratherium was one of the first bovids to enter North America. It appeared on this continent during the early Pleistocene, long before the first bison arrived from Eurasia. It went extinct about 11 500 years ago.

Late Pleistocene shrub-ox remains are known from fossil finds spanning from northern California to central Mexico. In the East they were distributed at least into Illinois.

Euceratherium was massively built and in size between a modern American bison and a musk ox. A specimen was estimated to have a body mass of 607.5 kg (1 339 lb). On the basis of preserved dung pellets, it has been established that they were browsers with a diet of trees and shrubs. They seem to have preferred hilly landscapes.

Photo: Robert Bruce Horsfall, 1913, Scott (1913)

Permission: Public Domain

Text: Wikipedia

References

- Prothero, D., Schoch R., 2003: Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals, Johns Hopkins University Press

- Scott, W., 1913: A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere, MacMillan Company, 1913 - 693 pages

- Surovell, T., Grund B., 2012: The Associational Critique of Quaternary Overkill and Why It is Largely Irrelevant to the Extinction Debate American Antiquity, Volume 77, Number 4, October 2012

- Surovell, T., Finely J., Smith, G., Brantingham, P., Kelly R., 2009: Correcting Temporal Frequency Distributions for Taphonomic Bias Journal of Archaeological Science, 36:1715-1724.

Coming originally from Africa, the mastodons invaded Europe and Asia 18 million years ago. They made their way to North America via the Bering Bridge 10 million years ago and finally reached South America two million years ago, after the isthmus of Panama was formed roughly three million years ago, an event that made the recent ice ages possible. The development of the tusks and of the trunk reflects the evolution of the mastodons during the Miocene, which lasted from 23 million years ago to 5 million years BP.

Coming originally from Africa, the mastodons invaded Europe and Asia 18 million years ago. They made their way to North America via the Bering Bridge 10 million years ago and finally reached South America two million years ago, after the isthmus of Panama was formed roughly three million years ago, an event that made the recent ice ages possible. The development of the tusks and of the trunk reflects the evolution of the mastodons during the Miocene, which lasted from 23 million years ago to 5 million years BP. The Manis Mastodon - A newly analysed mastodon rib bone shows that Native Americans were using bone-pointed weapons to take down big game nearly a thousand years earlier than thought, according to a new study. Images of the rib show a broken bone projectile point still stuck where a hunter drove it in 13 800 years ago. The rib was found near the town of Sequim on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, in the late 1970s. Radiocarbon analysis, DNA samples, genetics work, and other modern techniques recently revealed its true age.

The Manis Mastodon - A newly analysed mastodon rib bone shows that Native Americans were using bone-pointed weapons to take down big game nearly a thousand years earlier than thought, according to a new study. Images of the rib show a broken bone projectile point still stuck where a hunter drove it in 13 800 years ago. The rib was found near the town of Sequim on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, in the late 1970s. Radiocarbon analysis, DNA samples, genetics work, and other modern techniques recently revealed its true age.