Back to Don's Maps

Forgeries, Hoaxes and Curiosities

The Problem of the 'Bridles'

All photos and text below concerning the bridles/bâtons come from the excellent book 'Secrets of the Ice Age' (1980) by Evan Hadingham.

![]()

![]() A bâton de commandement (left) from La Madeleine in the Dordogne region, and (right) an undecorated example from the Russian Ukraine, shown here roughly at the same scale. (Note the two holes of different sizes in the left hand example. Are these different sized holes for different sized spears, or are they different sizes for purposes of a bridle? Don)

A bâton de commandement (left) from La Madeleine in the Dordogne region, and (right) an undecorated example from the Russian Ukraine, shown here roughly at the same scale. (Note the two holes of different sizes in the left hand example. Are these different sized holes for different sized spears, or are they different sizes for purposes of a bridle? Don)

Although the cave bears that prowled the pine forests of Érd near modern Budapest during the Mousterian period are not likely to have been tamed, there were other species that were far more amenable to human control. At the turn of the century an excavator of a prehistoric site (La Quina, in the Charente district of southwest France) noticed unusual traces of wear on the front incisor teeth of horses dug up from the Mousterian layers. These marks resembled those on modern teeth that result from the "tic" or nervous chewing habit of horses shut up in captivity, where boredom drives them to nibble incessantly at hard objects.

A few years later, in 1915, a lengthy study of some 16 000 modern horses was published, comparing the teeth of those kept tethered up with others roaming in relative freedom on the North American prairies. This study concluded that the nervous "tic" and its associated pattern of tooth wear is never present on animals free to wander at will. Could it be, then, that some Mousterian communities kept corrals of horses at certain times of the year, facilitating a control over animals normally undreamed of for this remote period or for many thousands of years afterward? It may be significant that the excavator of La Quina also found no less than seventy-six of the mysterious stone spheres in the Mousterian layers that, if they formed parts of bolas (as suggested earlier), could have been used to bring down and capture animals alive. In any case, the problem of the peculiar tooth wear brought to light sixty years ago deserves to be reexamined with modern techniques.

A more startling claim, first advanced in the 1870s and revived recently by a British scholar, Paul Bahn, is that we may be able to recognize actual animal bridles among Paleolithic bone objects. This may seem a very far-fetched idea indeed, considering that horses are conventionally thought to have been domesticated in Asia sometime after 3 000 BC. The arguments concern a strange type of object known by the picturesque term "commanders' maces" (bâton de commandement), which nevertheless do not seem to have been items of military insignia. These objects take the form of pierced staves of reindeer horn or bone, with a hole smoothly worked all the way through the branching point of the antler, usually shaped to a T or Y outline. bâtons without any form of surface decoration are known as early as the Aurignacian period from sites in the Dordogne, and they continued to be manufactured in increasing numbers right into the final centuries of the Magdalenian. As in the case of so many other forms of decorated bone work, elaborate animal carvings do not appear regularly until the middle Magdalenian, When depictions of horses are the most common theme. During this period, prehistoric engravers concentrated more attention and accomplishment on the bâtons than on any other item of equipment apart from the spear-thrower, which suggests that by this time the curious rods had acquired a special significance. The Magdalenian carvers seem to have delighted in the difficulties of decorating the narrow, rounded surfaces with a fine tracery of complex and well-proportioned animal forms,, Today, we can only grasp the total design when it is "decoded" in a single flat plane with the help of a cast of the entire rolled-out surface.

The quality of this carving and the fragility of some of the actual bâtons themselves make it difficult to believe that certain examples could ever have played a practical function. The idea of a sacred, symbolic wand may not, then, be improbable. During the seventeenth century, sorcerers among the Lapp reindeer herders used an identical type of object to beat a magic drum while they were in the midst of prophetic trances. Nevertheless, the signs of wear on some bâtons, especially around the inner edge of the hole, have inspired many ingenious, practical theories. One idea compares the prehistoric bâtons with identical objects worn by some recent Eskimo hunters as a kind of necktie under the throat. A more likely suggestion, one that is widely accepted by archaeologists, is that the bâtons were used as an aid in correcting the natural curvature of antler and ivory shafts intended for use as arrows and spears. According to one reconstruction, the shaft material was first softened over heat and steam; then one end of the shaft was wedged in the hole and the rest bound tightly under tension against the long arm of the bâton until it became straight. However, the only researcher to study the traces of wear around the holes concluded that the marks resulted from the friction of a soft strap (so could they be handles for slings, this investigator asked?).

( Note: I wonder if these bâtons have ever been found in pairs? Or are they like the ubiquitous thongs ( flip-flop rubber sandals patterned after Japanese footwear ) washed up on Australian beaches, and only ever found singly? - Don )

Horse bridles of a traditional type from Sardinia with wooden parts superficially resembling the prehistoric bâtons.

Horse bridles of a traditional type from Sardinia with wooden parts superficially resembling the prehistoric bâtons.

Yet another theory-the one that chiefly concerns us here-is that the bâtons formed the solid cheek pieces of leather or fibre harnesses that were slipped over the heads of horses or reindeer. In practical terms, such a use is quite convincing, for exactly similar antler pieces were traditionally employed in Sardinia for controlling horses through pressure exerted on the muzzle. Similarly, the Samoyeds of Siberia exercised some sort of control over the domesticated reindeer that pulled their sledges by tugging at the reins joined to simple head collars through the holes in pierced antler staves. Despite the feasibility of the bridle theory, there is no obvious reason why we should prefer it to any of the other ingenious ideas advanced to account for the bâtons; indeed, to accept it would mean adopting the unconventional view that horses or reindeer were domesticated by Paleolithic hunters.

Some fascinating and ambiguous evidence provides unexpected support for the bridle theory, however. Like most of the early antiquarians who had excavated in the Ice Age caves, Édouard Piette for many years regarded the horse and reindeer bones he recovered as simply representing the remains of wild animals brought down by traditional hunting methods. In 1889, however, he startled the prehistorians assembled at an international congress by delivering an address on "The Question of Reindeer Domestication," in which he maintained that the high achievements of the Paleolithic engravers and toolmakers must be the product of a stable, sedentary society, based on an economy of domesticated animals. What had changed his mind? Piette explained that he had found several carvings at Mas d'Azil where the horses have a noseband. The semi-domestication of these animals is thus well established. Nothing proves that man harnessed them, nor made them pull loads, nor gave milk, but why should they not have raised them in herds and have known how to lead them?'

Some fascinating and ambiguous evidence provides unexpected support for the bridle theory, however. Like most of the early antiquarians who had excavated in the Ice Age caves, Édouard Piette for many years regarded the horse and reindeer bones he recovered as simply representing the remains of wild animals brought down by traditional hunting methods. In 1889, however, he startled the prehistorians assembled at an international congress by delivering an address on "The Question of Reindeer Domestication," in which he maintained that the high achievements of the Paleolithic engravers and toolmakers must be the product of a stable, sedentary society, based on an economy of domesticated animals. What had changed his mind? Piette explained that he had found several carvings at Mas d'Azil where the horses have a noseband. The semi-domestication of these animals is thus well established. Nothing proves that man harnessed them, nor made them pull loads, nor gave milk, but why should they not have raised them in herds and have known how to lead them?'

Piette's views, stated modestly enough at the conference, became increasingly fervent as the years passed and as more of the curious "cut-out" carved horse heads came to light. The climax came in 1893, when an engraved bone piece was discovered in the cave of St. Michel d'Arudy, situated, like Piette's famous site at Le Mas d'Azil, in the foothills of the Pyrenees. (Photo at left) This spirited carving shows a horse head oddly divided up into panels, with an abstract row of chevrons partly covering the lower cheek. This, for Piette, was incontrovertible evidence for the existence of head collars and the final proof of his domestication theory. His views, however, awoke bitter and at times unreasonable opposition among the leading prehistorians of the day. Even the youthful Abbé Breuil, who considered the problem at length, eventually changed his mind and decided against the reality of the bridles. He examined the entire range of engraved bone silhouettes and supported the idea that the curious lines and panels carved on the horse muzzles represented stylized impressions of their coat markings or muscular structure. Because the weight of contemporary archaeological opinion fell against his theories, Piette's views were largely ignored in the years following his death in 1906.

Piette's views, stated modestly enough at the conference, became increasingly fervent as the years passed and as more of the curious "cut-out" carved horse heads came to light. The climax came in 1893, when an engraved bone piece was discovered in the cave of St. Michel d'Arudy, situated, like Piette's famous site at Le Mas d'Azil, in the foothills of the Pyrenees. (Photo at left) This spirited carving shows a horse head oddly divided up into panels, with an abstract row of chevrons partly covering the lower cheek. This, for Piette, was incontrovertible evidence for the existence of head collars and the final proof of his domestication theory. His views, however, awoke bitter and at times unreasonable opposition among the leading prehistorians of the day. Even the youthful Abbé Breuil, who considered the problem at length, eventually changed his mind and decided against the reality of the bridles. He examined the entire range of engraved bone silhouettes and supported the idea that the curious lines and panels carved on the horse muzzles represented stylized impressions of their coat markings or muscular structure. Because the weight of contemporary archaeological opinion fell against his theories, Piette's views were largely ignored in the years following his death in 1906.

Grotte de St Michel, D'Arudy.

Horse head showing designs on the head.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Reconsidering the problem of the bone horse heads today, it must be admitted that there is a considerable variety in these depictions, whatever their inspiration. Some bear no traces at all of the supposed bridles, while the clarity and detail with which the "cheek pieces" and "nose bands" appear on the other silhouettes vary considerably. One of the most delicate of the engravings was found lying on the surface of a cave floor near Arudy in 1975, only a few hundred meters from the site of the 1893 discovery. This new chance find has shaded lines and panels in exactly the same positions as on the St. Michel muzzle, although they are depicted much more faintly and certainly could pass as indications of the natural horse hair. Because of the peculiar, stiff style in which all the Pyrenean profiles are carved, a question mark will always hang over the exact significance of the patterns on their muzzles.

Reconsidering the problem of the bone horse heads today, it must be admitted that there is a considerable variety in these depictions, whatever their inspiration. Some bear no traces at all of the supposed bridles, while the clarity and detail with which the "cheek pieces" and "nose bands" appear on the other silhouettes vary considerably. One of the most delicate of the engravings was found lying on the surface of a cave floor near Arudy in 1975, only a few hundred meters from the site of the 1893 discovery. This new chance find has shaded lines and panels in exactly the same positions as on the St. Michel muzzle, although they are depicted much more faintly and certainly could pass as indications of the natural horse hair. Because of the peculiar, stiff style in which all the Pyrenean profiles are carved, a question mark will always hang over the exact significance of the patterns on their muzzles.

All the images on the right come from Le Mas d'Azil except Lortet at the top and the 1975 discovery at Espalungue, Arudy at the bottom.

Shown is a carved stone from La Marche, Vienne, Western France, showing a horse head with numerous lines engraved over it, including some that closely resemble the outline of a halter.

Carving from La Madeleine in the Dordogne that probably served as the weighted end of a spear thrower. Note the peculiar bridle pattern on the muzzle. This is a good argument against similar patterns on horses being representations of halters.

All photos and text above come from the excellent book 'Secrets of the Ice Age' (1980) by Evan Hadingham.

Pazyryk - Пазарык

A Pazyryk horseman, circa 300 BC.

The Pazyryk (Russian: Пазарык) is the name of an ancient nomadic people who lived in the Altai Mountains lying in Siberian Russia south of the modern city of Novosibirsk, near the borders of China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. In this part of the Ukok Plateau, many ancient Bronze Age barrow-like tomb mounds of larch logs covered over by large cairns of boulders and stones have been found. These spectacular burials of the Pazyryk culture closely resemble those of the Scythian people to the west. The term kurgan, a word of Turkic origin, is generally used to describe such log-barrow burials. This archaeological site on the Ukok Plateau is included in the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Pazyryks were horse-riding pastoral nomads of the steppe and some may have accumulated great wealth through horse-trading with merchants in Persia, India and China.

Photo and text: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pazyryk

Text below from: http://www.everyculture.com/Russia-Eurasia-China/Altaians-Orientation.html

Altaian is the general name for a group of Turkic peoples living in the region of the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia in the Altai Republic.

The Altaians constitute a group of related mountain peoples living beside the streams of the Altai complex of mountain ranges. This complex consists of the chief water-divide ranges, the South Altai, the Inner Altai, and the East Altai; the Mongolian Altai is connected to this mountain complex, rising to the southeast of the Siberian Altai region. The Altai system is located in the central part of southern Siberia, with Mongolia to the east and Kazakhstan to the south; it lies between 48° and 54° N and between 83° and 90° E. The mountains are of moderate elevation, with several reaching 4,500 meters; those higher than 3,000 meters are snowcapped throughout the year. The Altaians live in the broad plateaus, steppes, and valleys of the ranges.

The climate is continental, with considerable temperature swings, but is modified by the effect of the mountains, which cause a winter temperature inversion. In effect, the Altai forms an island of higher temperatures in winter than those found in the Siberian taiga to the north or in the Central Asian and Mongolian steppes to the south and east. The mean January temperature of the Chuya steppe, in the southeast of the region, is -31° C; winter temperatures fall as low as -48° C. The mountains form a nodal point for the gathering of precipitation. The main rainfall occurs in July and August, with a secondary and smaller period of rain in the late autumn. The western Altai has a mean annual rainfall of over 50 centimeters; the east is drier, receiving about 40 centimetres per year, or even less, and forms a transition to the more arid Mongolian steppe, farther east.

The Altai is rich in lakes and streams. The chief lakes of the region are Marka Kul in the south and Teletsk in the central part of the Altai region. In nearby parts of Siberia, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan there are much larger lakes: Zaysan Nur, Kara Usu, Ubsu Nur, and Kulunda. The Siberian rivers Ob, Irtysh, and Yenisei have headwaters in the Altai Mountains. The most important rivers within the Altai are the Biya, Katun, Bukhtarma, Kondoma, Ursul, Charysh, Kan, Sema, and Mayma.

Pazyryk Bridles

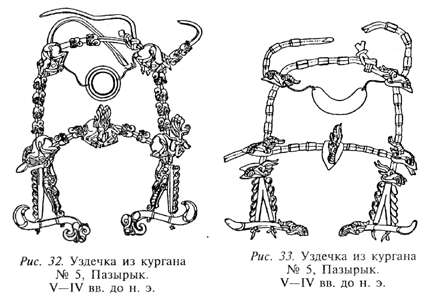

Рис. 32. Уздечка из кургана No. 5, Пазырык. 5—4 вв. до н. э.

Рис. 33. Уздечка из кургана No. 5, Пазырык. V—IV вв. до н. э.

Bridles from Mound No. 5, Pazyryk, 5th - 4th Century BC

Photo and text: СКИФЫ Тамара Т. Райс, Scythians by Tamara T. Rice

My thanks to Vladimir Gorodnjanski for access to this resource.

Рис. 34. Седельные ремни с ажурными узорами из кургана No. 1, Пазырык. V в. до н. э.

Рис. 35. Седло из кургана No. 1, Пазырык. V в. до н. э.

Fig. 34. Straps with openwork designs from mound No. 1, Pazyryk. 5th century BC.

Fig. 35. Saddle from mound No. 1, Pazyryk. 5th century BC.

Excavations and the resulting archaeological materials from the south of Russia shed appreciable light on the way that Scythians harnessed and decorated their horses. However the earlier archaeological materials from the South of Russia were not of good enough quality to show the complete technical details.

Here in Pazyryk were unearthed complete sets of harnesses, and the method used by Altaians to equip their saddle horses, as well as showing the fine details of their equipment.

Photo and text: СКИФЫ Тамара Т. Райс, Scythians by Tamara T. Rice

My thanks to Vladimir Gorodnjanski for access to this resource.

Comparison between the bits and the straps on the heads of horses from Pazyryk and similar areas in the European part of the steppe, shows that they were essentially similar.

Consequently it seems more than probable that although the more easily disintegrated parts of the harness were not recovered from Western deposits, still they were very similar to those in Pazyryk.

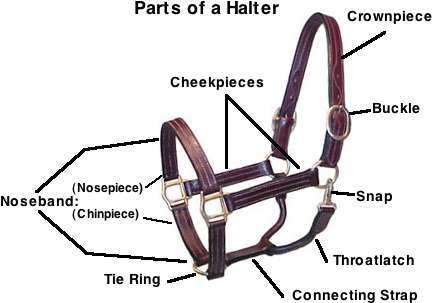

However, both in the east and the western plains, bits have consisted of parts reminiscent of the modern snaffle. A snaffle bit is the most common type of bit used while riding horses. It consists of a bit mouthpiece with a ring on either side and acts with direct pressure. In Pazyryk bridles consisted of thongs for the nose, cheeks, forehead and ears, and all of this was fastened with a buckle, located on the side of the head of the horse, similar to a halter.

Parts of a snaffle.

Photo: Wikipedia

Parts of a halter.

Photo: Wikipedia

The bridle was used in Assyria in the first half of the first millenium was also, probably, the same as were invented by the first equestrians.

In Pazyryk, a metal plate was located on the forehead of the horse, held by leather thongs. This plate, the thongs on the nose and cheeks, all crossings of thongs and even the thongs themselves were generously decorated with geometrical patterns and images of animals. They were punched into the thongs, or were appliqués of various materials.

All the thongs or straps were made of excellent leather, carefully dressed, richly decorated, and there were frequently golden plates, or parts covered with gold or lead foil.

The Gosford Glyphs

David Coltheart visits the "Kariong Egyptoid" site near Sydney, Australia

You can find the website at www.diggingsonline.com

The carvings are located within the Brisbane Water National Park inside a rock cleft that the local NPWS people refer to as the "Kariong Egyptoid" site. However, access is through private property and visitors should get permission to enter. Alternately, they can access the site through the national park via the "Lyre Trig" mountain above the site. The road rises gently to the summit of the mountain (241 m) and is well worth the half-hour climb because of the breath taking 360-degree view right over the Central Coast and down as far as Sydney. (Some locals have whimsically identified a nearby flat rock as a landing site for a space ship!

The carvings are located within the Brisbane Water National Park inside a rock cleft that the local NPWS people refer to as the "Kariong Egyptoid" site. However, access is through private property and visitors should get permission to enter. Alternately, they can access the site through the national park via the "Lyre Trig" mountain above the site. The road rises gently to the summit of the mountain (241 m) and is well worth the half-hour climb because of the breath taking 360-degree view right over the Central Coast and down as far as Sydney. (Some locals have whimsically identified a nearby flat rock as a landing site for a space ship!

Photo: David Coltheart

The area around Lyre Trig is famous for numerous Aboriginal carvings, including figures of giant kangaroos, men holding nulla nullas and spears, as well as carvings of hands and tools. The Aboriginal carvings, many in very inaccessible places, have been well researched and their positions noted long before the discovery of the so-called Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Entrance to the site

Entrance to the site

At the southern base of the Lyre Trig, in a very accessible location, two parallel sandstone cliffs, 1.5 m apart and 3 m high, run up the hill for about 15 metres. On both cliffs there are carved familiar Egyptian hieroglyphs, but among them are some stranger figures - a stick man hanging out the washing, a dog's bone, a very unEgyptian bell and several symbols that look like flying saucers.

Photo: David Coltheart

Alan Dash, a surveyor with the Gosford City Council between 1968 and 1993, first noticed the carvings about 1975. Thoroughly familiar with the area, he revisited the site several times over the next 5 years, each time observing that more and more carvings appeared on the rock face. He considered the engravings the work of an irresponsible vandal.

Neil Martin himself found the man responsible. "In 1984 1 was in the area helping to put out a fire", he told me. "As I came around the base of the hill, I could hear a noise like someone chipping stone. I walked over to the cleft and found an old Yugoslavian man, chipping the stone with a Sidchrome cold chisel. Because this was national park property, I confiscated the chisel and the man left. Because he was mentally handicapped, we took no further action, but I later gave the chisel to the local historical society. We never saw the old man again."

One of the so-called "cartouches".

Photo: David Coltheart

Since 1984 the cleft has gradually filled with leaves, fallen stones and dirt. However, the site has gained notoriety and taken on "spiritual significance." Since the 1990s, various people have illegally dug between the cliffs whether for treasure or looking for mummies is not clear. The NPWS rangers regularly confiscate tools and hammers left at the site. A hole has been dug between the cliffs by treasure hunters.

Much has been made of the supposed "age" of the inscription, suggested by the green lichen covering many of the hieroglyphs. Neil pointed out that lichen grows very quickly in the damp cleft. Growth is prolific in the presence of naturally occurring nitrates but even people touching the rock face transfer nutrients to the rock and this encourages the lichen to grow. Neil pointed out that gardeners sometimes paint a pottery garden pot with milk so that lichen will grow quickly and give the pot that "aged" look. This is a common technique used to hide scars made in rock.

Some of the Egyptoid carvings at Kariong appear to be smooth, giving them the false appearance of age. This is due to weathering in the sandstone rock, but differences in mineral content of even the same slab of sandstone will produce different degrees of weathering. However, most of the Egyptoid carvings still show crisp, sharp edges indicating recent cutting.

In 1984, Neil Martin, a ranger with the National Parks and Wildlife Service in Gosford, saw a local man carving the glyphs and confiscated his chisel.

Photo: David Coltheart

Mr David Lambert is an expert in rock art and in 2001 was the Rock Art Conservator of the Cultural Heritage Division of the NPWS. In 1983 he visited the site and saw the engravings freshly cut into the rock. The inside of each carving consisted of clean white sandstone with no evidence of organic or surface lichen growth, indicating the carvings were less than 12 months old. Pictures taken in 1983/1984 by the NPWS show the fresh cut rock and the spalling around the edges of the engravings indicating very recent carving. By contrast, the many genuine Aboriginal carvings in the area are much more rounded and smooth. Most of the Aboriginal carvings in this area have been dated to between 200 and 250 years old.

Photographs of the hieroglyphs taken in 1983 were sent to Prof. Nageeb Kanawati, head of the Department of Egyptology at Macquarie University, Sydney. Part of his reply to the NPWS reads: "I examined [the photographs] and think that the engravings are the work of someone who perhaps visited Egypt or saw some postcards of Egyptian monuments and wished to have some graffiti of what he saw. It is true that most of the signs are Egyptian, and two names of kings may be recognized, but the whole thing does not make sense at all. Simply a decorative graffiti using Egyptian signs."

Some of the more recently added glyphs. All the glyphs show sharp edges consistent with being recently carved in the sandstone, though some people want to believe that the glyphs are ancient. New carvings are being added to the site from time to time. Even on the day of my visit, Neil pointed out several new glyphs carved since his last visit, and indeed, the scratches in the rock were made into clean, white sandstone.

Photo: David Coltheart

Much has been made of the names of two kings that appear in adjacent "cartouches" (although it is significant that the Kariong cartouches are squared, not rounded). The two names are that of Khufu and an unknown person but could be "Neferankhru" which is similar to one of the names of Khufu's father, Snefem. The two names are coupled together under the same nomen and prenomen, indicating that the two names belong to the same person - unthinkable from our knowledge of Egyptian history. As one Egyptologist has commented, coupling the names together was the equivalent to spiritual suicide because it would separate the "ba" or soul from the creative essence of the body.

There are many other mistakes in the inscription. Some hieroglyphs are drawn incorrectly or face the wrong way, while at least one title, "Son of Re," was not used until well after the time of Khufu. Other hieroglyphs represent names from different periods of Egyptian history, separated by hundreds of years, which further indicates the inscription is a modern graffiti rather than an authentic ancient artefact.

Egyptologist Dr Gregory Gilbert concludes that the inscription is clearly a modern forgery, and not a good one at that.

The NPWS gets several calls a week from people convinced the glyphs were either carved by ancient Egyptians visiting Australia several thousand years ago, lost Phoenician sailors or by men in space ships. On an average weekend, dozens of people on a "spiritual search" hike through the bush in search of the "energy" supposedly generated at the site. As Neil pointed out, such beliefs may be valid, but shouldn't be used to rewrite Australian or Egyptian history!

Some of the glyphs are not Egyptian, and many that are Egyptian are incorrectly written. Some glyphs refer to Egyptian names that are hundreds of years apart but the overall inscription conveys no meaning whatsoever.

Photo: David Coltheart

Actually the carvings are part of genre of art and architectural styles triggered by the archaeological discoveries in Egypt in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb, in particular, sparked a round of movies, novels and memorabilia in the 1920s and 30s. Indeed, the "Tutmania" continues unabated today. It is no surprise then to find carvings of this nature in the rock and they have a valid place in Australian culture. Another example is the carving of the sphinx alongside a miniature pyramid made by Private Shirley in the national park near the road from Turramurra to Bobbin Head, in the northern suburbs of Sydney. The NPWS is slightly annoyed with the carvings because of the number of people who want to see them, the Internet sites suggesting they have ancient origins and the environmental damage done by visitors. The Gosford City Council has even received letters from visitors upbraiding the council for not doing more to conserve the "ancient" site and urging it to provide better public access.

Deciding that it is better to join the tourist trade rather than fight all the visitors, the NPWS runs tours through all the Central Coast's national parks. Known as the "Discovery Program" the NPWS offers 4WD tours, overnight camping trips, canoeing in the local rivers as well as guided walks, including walks for the over 50s. On request, tours can include the Egyptoid site at Kariong. There is a charge to cover costs, but bookings are welcome by phoning the NPWS on (02) 4320 4205.

Photo: David Coltheart

Flint Jack

Taken in 1869, this is a portrait of Flint Jack, the renowned forger of stone tools, sitting poised for the camera with a hammer in one hand and a piece of stone in the other. The early days of archaeological studies witnessed a vogue for the collection of stone tools, bringing with it a boom in the buying and selling of forged implements.

Photo, and text above from: Man before History by John Waechter

His real name was Edward Simpson, an occasional servant of Dr. Young, of Whitby. So called because he used to tramp the kingdom vending spurious fossils, flint arrow-heads, stone celts, and other imitation antiquities. Professor Tennant charged him with forging these wares, and in 1867 he was sent to prison for theft. (this text from http://www.bartleby.com/81/6584.html)

Photo: 'Archaeological Fakes' (in German 'Vorzeit

Gefalscht') by Adolf Rieth (Publ. Verlag Ernst Wasmuth, Tubingen,

1967 - translated Diane Imber, Publ. Barrie & Jackson, London,

1970)

The photo is

of Flint Jack as a much younger man, with hammer and flint and much shorter

dark whiskers, perhaps twenty years earlier than the photo above. His clothes seem old and worn, though perhaps they are his flint knapping clothes.

My thanks to Phil Knight, who found this source.

An article from the London Times, via the website

http://www.angelfire.com/ga/BobSanders/Whitby18601879.html

London Times

19 March 1867

"Flint Jack" - A notorious Yorkshireman - one of the greatest imposters of our times - was last week sentenced to 12 months imprisonment for felony at Bedford. The prisoner gave the name of Edward Jackson, but his real name is Edward Simpson, of Sleights, Whitby, although he is equally well known as John Wilson, of Burlington, and Jerry Taylor, of Billery-dale, Yorkshire Moors. Probably no man is wider known than Simpson is under his aliases in various districts - viz. "Old Antiquarian", "Fossil willy", "Bones", "Shirtless", "Cockney Bill", and "Flint Jack", the latter name universally.

Under one or other of these designations Edward Simpson is known throughout England, Scotland and Ireland - in fact, wherever geologists or archaeologists resided, or wherever a museum was established, there did Flint Jack assuredly pass off his forged fossils and antiquities. For nearly 30 years this extraordinary man has led a life of imposture. During that period he has "tramped" the kingdom through, repeatedly vending spurious fossils , Roman and British urns, fibulae, coins, flint arrow-heads, stone celts, stone hammers, adzes etc., flint hatchets, seals, rings, leaden antiquities, manuscripts, Roman armour, Roman milestones, jet seals and necklaces, and numerous other forged antiquities.

His great field was the North and East Ridings of

Yorkshire - Whitby, Scarborough, Burlington, Malton, and York being the chief places where

he obtained his flint or made his pottery. Thirty years ago he was an occasional servant to

the late Dr.Young, the historian, of Whitby, from whom he acquired his knowledge of geology

and archaeology, and for some years after the doctor's death he led an honest life as a

collector of fossils and a helper in archaeological investigations.

Photo: http://lithiccastinglab.com/gallery-pages/2005aprilhistoryofflintknappingpage2.htm

This projectile point was signed by Flint Jack, at a time when he had become famous enough that such a keepsake was worth having.

He imbibed, however, a liking for drink, and he admits that from that cause his life for 20 years past has been one of great misery. To supply his cravings for liquor he set about the forging of both fossils and antiquities about 23 years ago, when he "squatted" in the clay cliffs of Bridlington Bay, but subsequently removed to the woods of Stainton-dale, where he set up a pottery for the manufacture of British and other urns, and flint and stone implements, with which he gulled the antiquaries of the three kingdoms.

In 1859, during one of his trips to London, Flint Jack was charged by Professor Tennant with the forgery of antiquities. He confessed, and was introduced on the platform of various societies, and exhibited the simple mode of his manufacture of spurious flints. From that time his trade became precarious, and Jack sunk deeper and deeper into habits of dissipation, until at length he became a thief, and was last week convicted on two counts and sent to prison for 12 months.

Piltdown Man

This hoax is extensively covered elsewhere, but these photos may be of interest.

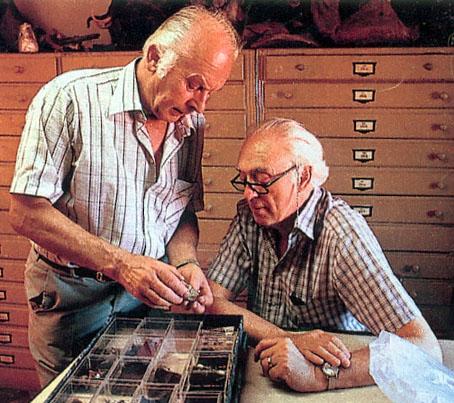

Excavating the Piltdown gravels in 1911, with Dawson (right) and Smith Woodward (centre)

Photo: Man before History by John Waechter.

A painting made soon after the Piltdown finds. Standing on the right of the group are Smith Woodward (bearded) of the London Natural History Museum and Charles Dawson, the discoverer of the remains. Note the reproduction of a painting of Darwin on the wall looking down on the group.

Photo : Man before History by John Waechter

And the great man himself.

Photo: New Scientist 5th November 2005

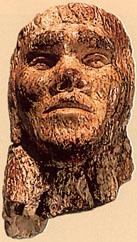

The Fake Věstonice Venus II

The fake Věstonice Venus II

Source: Facsimile on display, Dolní Věstonice Museum

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

The so-called counterfeit Vestonice Venus II

Dr. Jos. Skutil and dr. Al. Stehlik.

(translated and abridged from the Czech by Don Hitchcock)It is an event well remembered from earlier this year when there appeared the exceedingly strange circumstances surrounding the alleged Palaeolithic sculpture, allegedly originating from Dolní Věstonice, which very quickly gained the name 'Věstonice Venus II'.

When the statue was offered for sale overseas, at an enormously overpriced amount, police, at the request of the relevant authorities, charged with the protection of monuments and exports, seized the object from the then owner, F. Mullandrovi, and presented it for study to Prof. Dr K. Absolon, whose report was published on 23rd January 1930 by almost all daily newspapers. The report was damning with respect to its authenticity, identifying the statue as 'poor, made recently, an amateurish carved forgery' and that it should be referred for examination by a suitable criminological investigation.

Affirming this completely hostile verdict was State Conservator Dr Eng. I. L. Cervinka, as well as the Viennese Museum Director Dr Joseph Bayer of Vienna, who claim the sculpture is a 'modern, clumsy fake'.

It has been determined that the sculpture has no relationship to known Palaeolithic material, and displays a mental culture quite foreign to the period. However, because of the technical nature of the piece, by carving and scraping, there is no way to confirm or deny its Palaeolithic authenticity on this basis alone.

Report on the fake Věstonice Venus II

Source: Display, Dolní Věstonice Museum

The Mammoth Ivory Male head from Dolni Vestonice

A possible forgery

Click on each of the images to see a larger version

|

|

|

|

Since these photographs were published in the National Geographic in October 1988, and Plains of Passage was published in 1990, Jean Auel could well have used it as the model for Brugar, the person of mixed spirits described in Plains of Passage as having lived at Dolni Vestonice.

Eight centimetre high male head carved of mammoth ivory dated at 26 000 years BP.

Note that the figure has very heavy brow ridges. The figure has been stated to have a beard, but this feature is not obvious from the photographs.

Note also that Paul Bahn writing in 'Journey through the Ice Age', says that the head may be a fake. His main argument seems to be lack of provenance (meaning that it was not found by a recognised and trusted archaeologist, or with reliable witnesses to the discovery) and that the style is too modern. He also says that the Lady of Brassempouy (the ivory carving of Ayla) may be a fake.

The following text is from The National Geographic October 1988, and is written by Alexander Marshack.

Alexander Marshack is a professor of Palaeolithic Archaeology at Harvard University's Peabody Museum. He is amongst many other things a fine photographer and science writer

The head was an extraordinarily powerful male head with staring eyes, pinpoint holes in the irises, heavy brows, a strong upturned nose and long deeply incised hair. The smaller piece was a lock of longer hair. This lock of hair appeared to have been carved to curve around a staff.

A Czech family living in Australia, who prefer anonymity, had brought the carving to New York for Alexander Marshack to study.

This bust was discovered in the 1890s in a field near Dolni Vestonice, a village in which archaeologists, beginning in the 1920s, had found Ice Age works of art. Excavation continues there today, directed by Dr. Bohuslav Klima.

Dr Klima is a distinguished researcher in prehistory, and is at present an associate Professor in the Department of History at the University of Brno. He is a specialist in the Upper Palaeolithic in Central Europe, and is also the Director of the Archaeological Institute of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Brno.

The only other human head from the Ice Age that had eye sockets, eyeballs, and lids was the realistically carved female with a bun excavated in a 26 000 year level at Dolni Vestonice. Pieces of the ivory lamellae, like layers of an onion, had flaked off, leaving an uneven surface and an unfinished look. Later when Alexander Marshack reexamined this head in Czechoslovakia, and cleaned it he found incised nostrils, a detail not noted before, that resembled the style of the male head. Were these accidental similarities or aspects of a regional Ice Age style?

His initial microscopic analysis indicated that the male head had been broken in several places, glued together, and covered with a protective coating. He was told by the owners that the piece had been dipped in horse glue, once a common method of preserving bone. The ivory had apparently been shaped with flint tools. Many grooves were striated and changed configuration as the line curved. A steel blade would not make these patterns. Some strokes were overlaid with encrustations of sand and minerals that had apparently accumulated over time. Natural cracks, also filled with minerals, crossed the engraved lines, suggesting that weathering had occurred after the piece was carved.

The bottom had been sawed horizontally at about the shoulder line. Marshack had seen fine-toothed blades from the Dolni Vestonice collection that might, when hafted, have been used to saw ivory in this way. The nostrils and eyes presented a special problem. They appeared to have been cleaned, and even recarved, and then covered with paraffin.

The protruding brow is similar to that on a skull found in Brno, Czechoslovakia, in 1891.

X-ray diffraction at the Peabody Museum revealed the presence of iron oxides, which give the artifact its reddish brown coloration, and fluorapatite, the result of an exchange between the ivory and minerals in the soil. Both suggest long burial in the ground.

The British Museum had seen the piece once before. In the late 1940s the museum had been asked to authenticate the piece but had to return it when the owners moved to Australia; the museum may have put the paraffin in the eyes as a preservative. Museum experts now told Marshack it would be difficult, if not impossible, to fake the complex changes that had occurred in the ivory.

Clearly the ivory needed to be dated, and, more important, the carving itself. Accelerator carbon-14 dating was not feasible because it would consume a portion of the statuette. Marshack contacted Dr. Edward Zeller, director of the Radiation Physics Lab at the University of Kansas Space Technology Center, who became intrigued with the problem. He suggested alpha-particle spectral analysis to locate radioactive elements useful in estimating age. Working with fragments at first, Ed found uranium in surprising quantities. Uranium would enter the tusk only after its burial in sediment or sand where groundwater containing traces of uranium was seeping. More startling were the high counts of radium and other radioactive products of uranium decay.

While Ed was testing, Marshack detoured to Czechoslovakia on his way to a conference in Italy. He wanted to learn about soil conditions in the area of Dolni Vestonice and confer with Dr. Klima. He learned that uranium, a valued resource after World War II, had been located in the highlands northwest of Brno. Rainwater draining these heights may have reached the lowlands where the head was reportedly found. Klima said, 'We have so many unique things from Dolni Vestonice and Brno -the 'marionette', the oldest fired clay figures, the 26 000 year old female head - it would not surprise me to find here the oldest male image.'

Back in Kansas, Ed Zeller and his associate Dr. Wakefield Dort, Jr., a Pleistocene geologist now had the carved hair piece to test. They placed it in the counting chamber of the alpha particle spectrometer for 72 hours. The final ratios of uranium to decay products suggested that the carved surface of the ivory may be about 26 000 years old.

The scientists envision this Ice Age scenario: Sometime after a mammoth died, someone carved a piece of its tusk. The carving became buried in sediment or sand, where it absorbed uranium, iron oxide, and fluoride from the groundwater. The calcium phosphate of the ivory absorbed the minerals, especially the uranium. At the same time, radioactive decay set in, leaving its by-products at levels that require thousands of years to build up to the present reading. If the head had been carved anytime in the past few centuries, the decay products on the surface would have been cut away. 'Even Madam Curie couldn't fake that effect.' Ed said. He and Dort have no doubt that the carving is ancient, but the precise age has yet to be confirmed.

In July 2008 I received this very interesting communication from Danylo Derkacz (a pseudonym):

I am a retired neuropathologist and part time forensic pathologist who has dissected and examined microscopically about 1 200 human heads and brains.

1) the ivory head is carved by someone with training and talent.

2) the head makes no sense physiologically, genetically, medically or culturally.

a) medically it represents the head of a microcephalic individual who even with today's medical and social care would not survive puberty.3) neither today nor then would any artist produce a labor intensive sculpture of a village idiot with microcephaly.

b) the supraorbital ridges are those of a Neandertal but the head lacks the prognathia and recessed mentum (chin) of a Neandertal and has it protruding like that of H. sapiens sapiens.

c) the upturned nose is typical of a modern Slovyan (Slav) who at the time of discovery were considered as stupid peasants.

4) the nose of the ivory figure is so exaggerated that is better interpreted as that of a tertiary syphilitic which was then common in the pre-penicillin era and pre sulfonamides era.

In summary:

I think it is a first half of the 20th century fake and caricature of the fashionable (at that time) concept of Neandertals admixed with westerners as an expression of disrespect for Slavs.