Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to the review of hominins

Back to the review of hominins

Mousterian (Neanderthal) Sites

Mousterian (Neanderthal) Sites

Back to Venus figures from the Stone Age

Other Mousterian (Neanderthal) Sites

Click on the photos to see an enlarged version

Two good articles:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC165806/pdf/1006926.pdf

http://www2.uiowa.edu/dragon/Natural%20History%20Magazine%20%20Feature.htm

Le Masque Moustérien de la Roche-Cotard à Langeais (Indre-et-Loire)

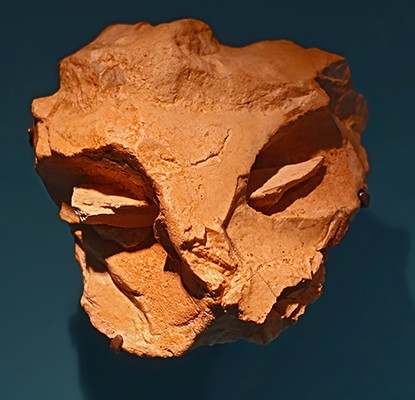

The site of la Roche-Cotard was discovered at the beginning of the 20th century but the Mousterien level (Roche-Cotard II), located in front of the opening of the cave, has been known only for 25 years.

In this dwelling site a very special object undoubtedly prepared by humans was discovered: it is a flint having a natural hole in which a small piece of bone has been placed. This object which makes one think of a human or animal face is an exceptional witness of the slow advance of humanity towards the beginning of illustrated art.

Text: By Jean-Claude Marquet, http://ma.prehistoire.free.fr/masque.htm

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Facsimile, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Location.

Photo: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/3256228.stm

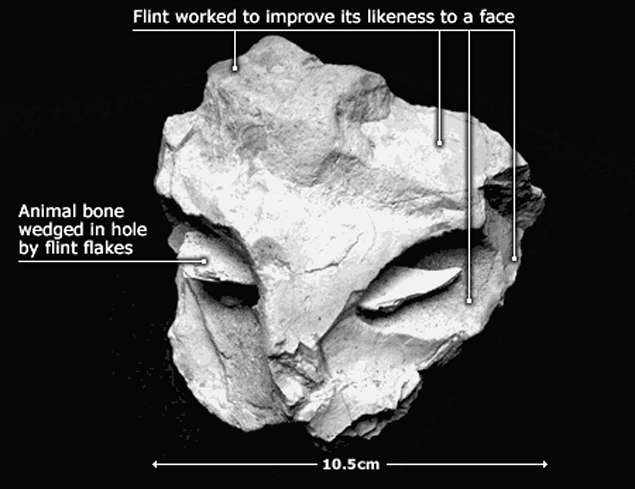

"The Mask" consists of a small flat flint which was modified to accentuate its resemblance to a face:

(1) a small piece of bone was inserted in a natural hole in the stone and fixed by two small stones;

(2) the stone was then improved to obtain greater symmetry.

"The Mask" is regarded as "a proto-figurine", one of the first steps towards the art of the upper Paleolithic. It is an exceptional object because the mousterian culture is not known to give this type of artistic production.

If Mousterian civilization is specific to Neandertals in Europe, "the Mask" thus leads us to think that Neandertals were capable of an artistic production more advanced than than anyone suspected until now.

This protofigurine is a flint improved by Mousterians to accentuate the appearance of a face which the stone offered.

Text: By Jean-Claude Marquet, http://ma.prehistoire.free.fr/masque.htm

This interesting article below comes from the BBC, at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/3256228.stm

A flint object with a striking likeness to a human face may be one of the best examples of art by Neanderthal man ever found, the journal Antiquity reports.

The "mask", was recovered on the banks of the Loire in France.

It is about 10 cm tall and wide and has a bone splinter rammed through a hole, making the rock look as if it has eyes.

Commentators say the object shows the Neanderthals were more sophisticated than their caveman image suggests.

"It should finally nail the lie that Neanderthals had no art," Paul Bahn, the British rock art expert, told BBC News Online. "It is an enormously important object."

It is described in Antiquity by Jean-Claude Marquet, curator of the Museum of Prehistory of Grand-Pressigny, and Michel Lorblanchet, a director of research in the French National Centre of Scientific Research, Roc des Monges, at Saint-Sozy.

The mask was found during an excavation of old river sediments in front of a Palaeolithic cave encampment at La Roche-Cotard.

Tool and bone discoveries suggest Neanderthals used the location to light a fire and prepare food.

Triangular in shape, the object shows clear evidence, the researchers say, of having been worked - flakes have been chipped off the block to make it more face-like.

The 7.5-cm-long bone has also been wedged in position purposely by flint fragments.

Marquet and Lorblanchet write in Antiquity: "We think that this is indeed a 'proto-figurine'; that is, a small flint block whose natural shape evokes a crudely triangular human face - or a mask if one notes that it is primarily the upper part of the face that is concerned, like a carnival mask, or, rather less clearly, an animal face, perhaps a feline?

"It was not only picked up and brought into the habitation, but was also modified in various ways to perfect its resemblance to a face: the forehead, the eyes underlined by the bone splinter, the nose stopped at its extremity by an intentional flake-removal, and the rectified cheeks."

They are convinced this object is no accident of geology. Jean-Claude Marquet told BBC News Online: "The sliver of bone was pushed in forcibly and wedged with two pebbles.

"Chance could not have inserted the stones in between the bone and the block in such a balanced way, with the two ends coming out equally either side."

Bahn believes the Roche-Cotard mask should set the record straight on Neanderthals' artistic capabilities.

"There are now a great many Neanderthal art objects. They have been found for decades and always they are dismissed as the exception that proves the rule.

"This is not just a fortuitous bone shoved into a hole in a rock. Whether the Neanderthal artist saw a rock that looked like a face and modified it, or conceived the thing from the start - who knows? Either way it is pretty sophisticated."

And Marquet added: "This object shows that art was not born in the brain of Homo sapiens but much earlier in the brains of predecessors like the Neanderthal man and even, no doubt, in Homo erectus.

"Neanderthal man was not a coarse character incapable of elaborate mental thought. Here, he has used a rock with a particular natural form to make a face emerge from its shape."

Perhaps the oldest example of modern human art generally accepted by the scientific community would be the 77 000-year-old engraved ochre pieces found in the Blombos Cave in South Africa.

However, earlier this year, scientists announced the discovery of the oldest Homo sapiens skulls. These 160 000-year-old fossil bones had been polished after death.

This mortuary practice suggests at least these early people were abstract thinkers, capable of analysing ideas of life and death.

Text and photo adapted from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/3256228.stm

Mask from La Roche-Cotard, Langeais, France

Circa 75 600 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Original, Private Collection

Excavations of Jean-Claude Marquet

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Mousterian from Biache-Saint-Vaast, France.

Skull of Biache 1, possibly of a woman, from Biache-Saint-Vaast, France.

Circa 180 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Collections du Musée d'Archéologie nationale - Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

The site of Biache-Saint-Vaast, in the Pas-de-Calais, has delivered many Levallois flakes retouched to form scrapers with convergent edges (mousterian points) which characterise the Mousterian, the main cultural group of the Middle Palaeolithic.Text above: Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

The study of the microwear found on the edges of these pieces shows that they were mainly used in woodworking. Other marks located at the base of these pieces imply the existence of removable technology. The damaged parts could be replaced all the more easily, because they were standardised.

This standardisation of the fitting of the bone or flint point to its handle or shaft, invented in the Middle Palaeolithic, constitutes huge progress, since it increases the grip of the tool on its handle or shaft, and increases the efficiency of the whole weapons/tool system.

On the Umm-el-Teel deposit, in Syria, a scraper bears traces of paraffin-mixed asphalt, materials used as glue for fitting.

In Europe, birch bark glue was used for attaching a flint or bone tool to its handle or shaft.

Mousterian from Biache-Saint-Vaast, France.

(left): This is labelled as a mousterian point with convergent sides.

( In fact it looks like a mousterian point that has been retouched to turn it into a well made and very useful perçoir or drill - Don )

(right): This is also labelled as a mousterian point with convergent sides.

( This point has been heavily retouched to turn it into what may be a spear point - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015, 2018

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Mousterian from Biache-Saint-Vaast, France.

(left): A simple convex racloir, or side scraper.

(right): This is labelled as a mousterian blade. ( note that it appears to have been used as a nosed scraper, a grattoir à museau, and has had a notch added - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015, 2018

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Mousterian from Biache-Saint-Vaast, France.

A denticulé, or denticulate tool, containing one or more edges that are worked into multiple notched shapes (or teeth), much like the toothed edge of a saw. Indeed, such tools have been used as saws, more likely for meat processing than for wood. It is possible, however, that some or all of these notches were used for smoothing wooden shafts or for similar purposes. These tools are part of the Mousterian tool industry.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Additional text: Wikipedia

The Mousterian of l'abri de la Rochette à Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère, in the Dordogne region

During the middle Palaeolithic, the concept of the biface hand axe evolved. Henceforth, the production of the cutting edges was integrated in the making of the piece from its conception, which confers on it a more standardised character. The bifacial hand axe is a versatile tool for cutting and drilling. It is above all characteristic of the facies known as 'Mousterien de tradition Acheuléene' (MTA) although it exists occasionally in other cultural groupings of the Middle Palaeolithic.

At the base of l'abri de la Rochette à Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère, in the Dordogne region, is a Mousterian layer of the Acheulian tradition.

The Mousterian of l'abri de la Rochette à Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère

Flakes from a nucleus of the upper Palaeolithic type.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

The Mousterian of l'abri de la Rochette à Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère

Nucleus of the upper Palaeolithic type, with unipolar semi-rotating debitage.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

The Mousterian of l'abri de la Rochette à Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère

Knives with blunted backs.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

The Mousterian of l'abri de la Rochette à Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère

Tool with convergent sides, a mousterian point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

The Mousterian of l'abri de la Rochette à Saint-Léon-sur-Vézère

Biface, hand axe.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Tablet of engraved sandstone

Tablet of engraved sandstone, Grotte de loup, from the excavation by G. Mazières

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Original, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Engraved sandstone tablet from la Grotte du Loup (Cosnac), France.

Circa 38 000 BP.

The Grotte de Loup is a very small cavity, marking the transition from the middle to the upper Palaeolithic. The principal layer, couche III, is well preserved and corresponds to the Final Mousterian. It contains a number of pieces which tend towards the Aurignacian, including altered nuclei, rabots (push scrapers), and very large burins.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Collections du Musée national de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac.

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Additional text: Leroi-Gourhan (1950)

Engraved bone

Engraved bone from Les Pradelles/Marillac, excavated by B. Vandermeersch

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Original, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Os strié, Les Pradelles/Marillac, Fouille B. Vandermeersch

40 000 year old Neanderthal tooth

Photo and text below adapted from:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23073824/displaymode/1176/rstry/23073771/

This Neanderthal tooth was found in southern Greece. Strontium isotope analysis shows that the individual spent part of its life 20 km away from where the tooth was found.

Most experts believe that Neanderthals roamed over very limited areas, but at the same time it is difficult to believe they would not have travelled some distance when hunting.

In any case, Neanderthals eventually spread over very large areas, so at least some of them had to have moved considerable distances, at least over generations if not individually.

"Neanderthal mobility is highly controversial," said palaeoanthropology Professor Katerina Harvati at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Harvati was part of the team that carried out the analysis on the tooth, found in a seaside excavation in Gythio in Greece's southern Peloponnese region in 2002.

The findings were published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The team from the Max Planck Institute, led by Department of Human Evolution professor Mike Richards and Harvati, analyzed tooth enamel for ratios of strontium isotope, a naturally occurring metal found in food and water. Levels of the metal vary in different areas. As it is absorbed by the body, an analysis of its levels can show where a person lived.

Eleni Panagopoulou of the Paleoanthropology-Speleology Department of Southern Greece said the levels of strontium isotope found in the tooth showed that this particular Neanderthal grew up in a different area — at least 12.5 miles away — from its discovery site.

"The analysis results ... will contribute to solving one of the central issues of paleoanthropology, that of the mobility of the Neanderthal," Panagopoulou said.

"Our findings prove that their mobility was significant and that their settlement networks were broader and more organized than we believed," she said.

Given that Neanderthals also coexisted with modern man in some parts of Europe, "one could presume that this mobility would facilitate the contacts of the two populations on a cultural and, perhaps, on a biological level."

Professor Clive Finlayson, an expert on Neanderthal man and director of the Gibraltar Museum, disagreed with the finding's significance.

"The technique is interesting, and if we could repeat this over and over for lots of (individuals) then we might get some kind of picture," he said.

"(But) I would have been surprised if Neanderthals didn't move at least 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) in their lifetime, or even in a year ... We're talking about humans, not trees." Copyright 2008 The Associated Press.

The quarry of hunters during the Mousterian period in central and eastern Europe. Each column represents the total animal remains at a particular site, divided into percentages of the main animals present. Sometimes the exact percentages were not properly recorded by the original excavator, and in such a case the column is shaded or else divided into equal segments.

The quarry of hunters during the Mousterian period in central and eastern Europe. Each column represents the total animal remains at a particular site, divided into percentages of the main animals present. Sometimes the exact percentages were not properly recorded by the original excavator, and in such a case the column is shaded or else divided into equal segments.

The map suggests that specialized hunting was practiced at 17-18 Mousterian sites. The record could simply reflect which animals were most numerous or vulnerable in a particular environment, but heavy concentrations on a single animal are likely to be due to some degree of human choice.

This map is a much simplified summary of the available evidence. Not every Mousterian site is shown, but the black dots give some idea of the main centers of settlement in the early Ice Age. For further details, see Gábori 1976. Les Civilisations du Paléolithique Moyen Entre Les Alpes et L'Oural, Akadéamiai Kiadó, Budapest pp. 197-206.

Photo and text: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham 1980

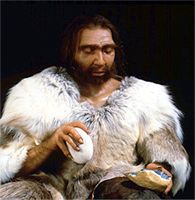

The first complete reconstruction of a Neanderthal

Whole at last. The first reconstruction of a complete Neanderthal skeleton reveals more clearly than ever the similarities and differences between us (far right) and them.

Whole at last. The first reconstruction of a complete Neanderthal skeleton reveals more clearly than ever the similarities and differences between us (far right) and them.

The reconstruction makes clear their larger, bell-like chest cavity and wider pelvis. Their bodies were also very compact and dwarf-like in shape, with effectively no waist, possibly as an adaptation against the cold.

Gary Sawyer of the American Museum of Natural History in New York city and Blaine Maley at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, wanted to shed light on the anatomy and stature of this cousin of modern humans, which died out nearly 30 000 years ago. They assembled the skeleton by taking casts of the most complete skeleton available, the La Ferrassie I specimen found in 1909 in the Dordogne valley in France. Then they filled in the blanks using casts taken from other Neanderthal collections from the same period, approximately 60 000 years ago (The Anatomical Record, Part 8: The New Anatomist, vol 283B, p 23). "It's the first time any human 'ancestor' has ever been fully reconstructed," says Sawyer.

Meanwhile, the oldest fossilised primate protein to have been sequenced, taken from a Neanderthal, was last week found to be identical to the human equivalent (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0500450102).

Text by Duncan Graham-Rowe

Text and photo from New Scientist 19 March 2005

Scientists Build 'Frankenstein' Neanderthal Skeleton

From:

http://www.livescience.com/history/050310_neanderthal_reconstruction.html

By Bjorn Carey

LiveScience Staff Writer

posted: 10 March 2005

Anthropologists have built a "Frankenstein" Neanderthal skeleton, the first and only full-body reconstruction of the species. The result, announced today, is a shape no one expected.

"It's almost like making my own fossil discovery," said Gary Sawyer, one of the skeleton's architects.

Sawyer, an anthropologist at the American Natural History Museum in New York, and his colleague Blaine Maley of Washington University, pieced together the skeleton using bones mostly from an individual known as La Ferrassie 1.

La Ferrassie 1 was missing its rib cage, pelvis, and a few other parts, so Sawyer and Maley had to scrounge around to find some parts.

"The missing parts had to come from another classic Neanderthal that was similar, if not identical, in size to the La Ferrassie man," Sawyer told LiveScience in a phone interview.

The spare parts came from Kebara 2, a 60 000-year-old skeleton discovered in Israel in 1983. Kebara 2 was previously known as the specimen with the best rib cage, pelvis, and vertebral preservation.

The La Ferrassie man was discovered in France in 1909 and is about 70 000 years old.

'Dwarfy-like beings'

Sawyer said the replacement bones are remarkably similar in size to La Ferrassie man - most were off by only a few millimeters.

Still, as the scientists pieced together the bones, something didn't look quite right. A rotund, bell-shaped torso, produced by a flared lower ribcage, and a pelvic region that looked slightly wide and feminine, began to form in front of their eyes.

"The biggest surprise by all means is that they have a rib cage radically different than a modern human's rib cage," said Sawyer. "As we stood back, we noticed one interesting thing was that these are kind of a short, squat people. These guys had no waist at all - they were compact, dwarfy-like beings."

Other bits and replacement pieces, mostly the ends of bones, were collected from half a dozen other Neanderthals. The remaining gaps were filled in with reconstructed human bones.

The finished product is "like Frankenstein," Sawyer said.

Even though the reconstructed fossil is made up of both Neanderthal and human bones, Sawyer doesn't believe that modern humans could have evolved from Neanderthals based on the pelvic and torso discrepancies between the two species.

Evolutionary side road

"There is no way that modern humans, I believe, could have evolved from a species like Neanderthal," Sawyer said. "They're certainly a cousin - they're human - but they're one of those strange little offshoots."

The reconstructed Neanderthal skeleton is currently on display at the Dolan DNA Learning Center in Cold Spring Harbor, NY. It will eventually go on permanent display at the American Museum of Natural History.

This research will be published in the March 11 issue of the Anatomical Record Part B: The New Anatomist .

Neanderthals were a relative of homo sapiens that co-inhabited Europe and parts of western Asia with hum from about 120 000 to 29 000 years ago. They were well adapted to the cold and were very muscular -- good traits for hunting large animals.

"They had very strong hands," Sawyer said. "If you shook hands with one, he would turn your hand to pulp."

Comparisons:

Neanderthal Height 5 feet 6 inches

Human Height 5 feet 9 inches

Neanderthal Weight 142 lb Human Weight 172 lb

Neanderthal Brain 1 200 - 1 700 cc

Human Brain 1 300 - 1 500 cc

Choice of foods

What little evidence there is indicates that many Ice Age communities in western Europe lived not in bleak and marginal surroundings, but that a wide range of animal and vegetable foods were there to be exploited throughout the year. Assuming that these guesses are correct, a vital question poses itself, one that affects our entire outlook on the stability and security of Paleolithic life: why should the hunters have chased one species of animal in preference to another? Why, in particular, did some hunting groups become so dependent on reindeer that the glacial period is often popularly known as the 'Reindeer Age'?

Photo: http://www.the-neanderthal-tools.org/?p=45

Clear choices were already made by hunters living in the very earliest centuries of the Ice Age. As mild climates imperceptibly gave way to long, sharp winters and and summers, people in central Europe 100 000 years ago deliberately selected the animal species that they pursued. Imagine a hunting station at that remote period, situated high over the Danube Valley at a spot now overlooking the suburbs of Budapest. Here, on the edge of the plateau of Érd, halfway between the mountains and the river, a group of hunters camped in two basins in the limestone, two little cavities side by side that both gradually filled up with soil, charcoal, animal bones, and Mousterian flint tools. The rock walls of the two cavities protected these occupation remains from being washed away and helped to preserve them to the present day.

The earliest human groups to settle at Érd, no doubt attracted by the shelter of the limestone walls, lived at the edge of a hill slope dominated by pine trees that, as the centuries wore on and the climate became more rigorous, gave way increasingly to larch. At the peak of one cold phase, about 60 000 years ago, there is evidence to show that July temperatures reached an average of 10° C (50° F) or more, while in January these figures dropped to a chilly - 10° to - 15° C (14° to 5° F). Not surprisingly, the hunters at Érd passed the winter elsewhere and spent only brief periods in spring and summer at the site. During the mild season, the surrounding landscape was not so desolate or forbidding as might be imagined, for among the 15 000 animal bones that can be identified, a wide range of nearly fifty species is present.

However, despite the presence of the bones of all these animals in small quantities, the Mousterians did not practice a "catch-as-catchcan" policy, an indiscriminate plundering of every species that they encountered. Instead, for a brief period of no more than two or three months in early spring, they concentrated their attentions on either newly born or one-year-old cave bears. The corpses of the bear cubs, which far outnumber the other species represented at the site, were dragged back in one piece to camp, and certain joints were stored in the smaller of the two limestone basins. The same hunters appear to have reoccupied Érd in the summer, when they left behind an identical range of tools but based their hunting mainly on horses and to a lesser extent on asses, rhinos, and deer. Unlike the bear corpses, the horses were dismembered on the spot, and only the head and limbs were carried back to base.

It is possible, of course, that this selection of certain animals was less the work of man than of nature and simply reflected the creatures that were most abundant or vulnerable in the local landscape. However, the heavy concentration on bears of such a narrow age group does suggest a deliberate human policy. Moreover, at the nearby site of Tata, set in an almost identical environment and occupied at roughly the same period as Érd, people using quite different tools concentrated heavily on the hunting of young mammoths. The lesson seems to be clear: long before the appearance of fully modern man or of the art objects of the Upper Paleolithic, people were already picking and choosing from the animal resources that surrounded them and were developing specific hunting tactics that they used successfully for centuries.

The hunting of some animals and not others is perhaps not surprising; all carnivores are to some extent selective of their prey. The intensive hunting of one species is a trait that seems to stretch very far back in the human record. Sites with the consistent remains of young animals selected from just a ew species go back at least as far as the Mindel glaciation, at least 300,000 years ago. However, a heavy dependence on one particular game animal is a feature that appears to spread and intensify in Europe with the appearance of more and more sites preserved during the last Ice Age.

What advantages could this specialization have brought? An intimate knowledge of the daily movements and behavior of one type of animal must have lessened the element of chance in hunting, and perhaps in some regions, this became a vital factor as climates became more severe and game more sparse. Equally, such a dependence exposed human communities to the peril of overexploitation, of pushing a particular herd beyond its limits and into extinction, facing the human group in turn with a sudden crisis of resources. The swiftness of this process should not be underestimated. Small Siberian family groups (of herders, not hunters) were totally dependent during the last century on reindeer, and once the numbers of these animals dwindled to a certain minimum of a few hundred animals, the herds were particularly liable to collapse under the impact of a whole range of possible dangers:

Any inclemency of weather, disease, man or animal with respect to such a herd is likely to reduce it suddenly and catastrophically below a point to which it can maintain either the family or itself.

It seems likely that the concentrated hunting of a single species would have exposed the hunters to greater risk from this sort of abrupt natural crisis.

An attempt to reconstruct the likelihood and impact of the failure of prehistoric reindeer herds on Ice Age hunting bands was the imaginative work of one London University lecturer, Nicholas David. His case study concerned the Perigordian culture, which became dominant in the Dordogne region during a comparatively mild interval of climate from about 26 000 B.C. At a slightly later period, beginning around 23 000 B.C., a distinct group of tools appears at several classic sites, notably the caves of Arcy-sur-Cure at its northernmost limits and Isturitz in the Pyrenees far to the south. The group is distinguished from the typical Perigordian mainly by its small, multiple-purpose blades with an angled cutting edge (known as Noailles burins).

The distinctive assemblages of these tools had persisted in the Dordogne for several centuries after 23,000 B.C., when it is clear that there occurred a definite decline in the numbers of sites occupied, suggesting a drop in population. After this temporary setback, the Noaillan flintworkers seem to have reasserted themselves, but with a slight change evident in their toolmaking preferences. They appear to have continued their activities until they "merged" with the Perigordian culture, after preserving something like 2 000 years of independence. The key problem is to account for the decline in population in the middle of this period, when no appreciable change is registered in studies of the comparatively mild climate. Did the Perigordians and the Noaillans suddenly quarrel over some intertribal dispute and resolve their grievances in a pitched battle somewhere along the banks of the Vézère.

David's close examination of the problem draws attention to the interesting fact that the economy of the Noaillan hunters in the central area of the Dordogne was different from its farthest outposts at Arcy and Isturitz. The animal bones recovered from excavations in the border regions demonstrate that the communities there exploited a broad range of quarry, including wild horses, red deer, and bovids. But in the valleys of the Vézère and the Dordogne, the Noaillan people relied almost exclusively on reindeer, which accounts for over 90 percent of the bones recovered from living sites.

This concentration on reindeer, David suggests, was a potential source of instability for the hunting groups, and is- a possible clue to the mystery of their sudden depopulation. Drawing on comparisons with the recent caribou hunters of Canada, David suggests that the reindeer could have been intensively exploited beyond the point at which they could successfully replace their dwindling numbers. Oncp the population of the reindeer had fallen below a certain minimum, the fate of the entire herd was swift and certain, and with it, the dependent hunting group also was doomed. A comparable failure of reindeer herds in late nineteenth-century Canada was provoked by the overspecialized hunting of the Naskapi Indians with their newly acquired rifles, hundreds of whom starved to death as a consequence. Those Paleolithic people who were fortunate enough to have survived the catastrophe of the collapsed reindeer herd might possibly have combined together some time later to form new hunting bands, accounting for the slight differences observable in the tool kits of succeeding centuries. Meanwhile, the communities in the Pyrenees and in the Cure valley with their varied and relatively secure subsistence continued to flourish throughout this period without any apparent calamities.

Text above: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham 1980

Neanderthal man at Le Moustier, overlooking the valley of the Vézère, in the Dordogne. Drawing by C. Knight, under the direction of H. Osborn.

Photo: H. Osborn, 'Men of the Old Stone Age' (1916)

From:

http://researchnews.osu.edu/archive/neander.htm

Neanderthal life no tougher than that of 'modern' Inuits

Image by Lee A. Spencer, Ph.D. from: origins.swau.edu/ papers/man/hominid/

Image by Lee A. Spencer, Ph.D. from: origins.swau.edu/ papers/man/hominid/

COLUMBUS, Ohio - The bands of ancient Neanderthals that struggled throughout Europe during the last Ice Age faced challenges no tougher than those confronted by the modern Inuit, or Eskimos. That's the conclusion of a new study intended to test a long-standing belief among anthropologists that the life of the Neanderthals was too tough for their line to coexist with Homo sapiens.

'Looking at these fossilized teeth, you can easily see these defects that showed Neanderthals periodically struggled nutritionally,' Guatelli-Steinberg said.'But I wanted to know if that struggle was any harder than that of more modern humans.'

And the evidence discounting that theory lies with tiny grooves that mar the teeth of these ancient people.

They thrived from about 200 000 to 30 000 years ago until their lineage failed for as-yet unknown reasons. Most researchers have argued that their life in extremely harsh, Ice Age-like environments, coupled with their limited technological skills, ultimately led to their demise. Homo sapiens arrived in Europe about 40 000 years ago and survived using more advanced technology. But the short lifespans of Neanderthals and evidence of arthritis in their skeletons suggests that their lives were extremely difficult.

That's where Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg's work comes in. An assistant professor of anthropology and evolution, ecology and organismal biology at Ohio State University, she published a recent study in the Journal of Human Evolution that changes our view of the Neanderthals' unbearable lives.

Guatelli-Steinberg has spent the last decade investigating tiny defects -- linear enamel hypoplasia -- in tooth enamel from primates, modern and early humans. These defects serve as markers of periods during early childhood when food was scarce and nutrition was low.

These tiny horizontal lines and grooves in tooth enamel form when the body faces either a systemic illness or a severely deficient diet. In essence, they are reminders of times when the body's normal process of forming tooth enamel during childhood simply shut down for a period of time.

'Looking at these fossilized teeth, you can easily see these defects that showed Neanderthals periodically struggled nutritionally,' she said.'But I wanted to know if that struggle was any harder than that of more modern humans.'

To find that answer, she turned to two collections of skeletal remains: One was a collection of Neanderthal skulls at least 40 000 years old from various sites across Europe; the other was a set of remains of Inuit Eskimos from Point Hope, Alaska. The Inuit remains, some 2 500 years old, are maintained by the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

She microscopically examined teeth from the Neanderthal skulls for signs of linear enamel hypoplasia, as well as other normal growth increments in teeth called perikymata, and compared their prevalence with those from the Inuit skulls.

'The evidence shows that Neanderthals were no worse off than the Inuit who lived in equally harsh environmental conditions,' she said, despite the fact that the Inuit use more advanced technology.

'It is somewhat startling that Neanderthals weren't suffering as badly as people had thought, relative to a modern human group (the Inuits).'

Guatelli-Steinberg's examination of perikymata offered snapshots of Neanderthal survival. Smaller than the linear enamel hypoplasia, perikymata are even tinier horizontal lines on the teeth surface. Each one represents about eight days of enamel growth so by counting their number, researchers can gauge the speed of tooth development - more perikymata mean slower growth of the tooth surface.

Guatelli-Steinberg counted perikymata within linear enamel hypoplasias, and was able to gauge how long these episodes of physiological stress lasted. The perikymata showed that periods of up to three months of starvation for both the Neanderthals and the Inuit were not uncommon. In fact, Guatelli-Steinberg found that Inuit teeth showed significantly more perikymata than did the Neanderthals, suggesting that the Inuit experienced stress episodes that lasted slightly longer than did those of the Neanderthals.

She is looking ahead to do a similar comparison of tooth defects among the European Cro-Magnon who thrived after the Neanderthals disappeared. Coupled with the results of this project, and that of earlier work with non-human primates, she hopes to improve researchers' understanding of just what information these tooth defects might reveal.

Along with Guatelli-Steinberg, Clark Spencer Larsen, professor and chair of anthropology at Ohio State, and Dale Hutchinson, associate professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina, worked on this project. Support for the research came from the L.S. B. Leakey Foundation .

Contact: Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg, (614) 292-9768; guatelli-steinbe.1@osu.edu .

Written by Earle Holland, (614) 292-8384; Holland.8@osu.edu .

Gorham's Cave

Text above from Wikipedia.

Gorham's Cave in Gibraltar, sculpted out of the cliffside by the sea, and occupied by prehistoric man over a period of 40 000 years.

Photo from: Man before History by John Waechter.

Text below from http://www.gib.gi/museum/p67.htm

John Waechter of the Institute of Archaeology in London was the first to excavate in Gorham's Cave in the 1950s. He described a well-stratified 16 m sequence of Late Pleistocene deposits in Gorham's Cave.

The current work in this cave has been concentrated largely on three exposed stratigraphic units towards the back of the cave. These cover three main time zones, Upper Palaeolithic with dates spanning 26-30 ka Before Present (BP), a group containing the youngest Middle Palaeolithic and dated at around 31-32 ka BP, and a third group which covers the main Middle Palaeolithic sequence which lies in and under units dated by a new accelerator date on charcoal of 45.3 ± 1.7 ka BP (OxA-6075) and above units dated between 80-100 ka BP by Uranium-series determinations.

Text below from http://www.showcaves.com/english/gb/region/GomezGibraltar.html

Sediments within the cave appear to have accumulated without interruption during the late Pleistocene. It remains to be proved whether or not they rest on beach material deposited during the high sea-level of the Last Interglacial about 120,000 years ago, when sea-level is unlikely to differ greatly to that of present day. If so, the over-lying deposits, were laid down between 100 000 and 10 000 years ago during the period of fluctuating climatic conditions known as the Last Ice Age. More certain is the evidence that during the period represented by the cave fill, Gibraltar must have been part of the mainland with a broad coastal plain covered with dunes stretching in front of the site.

The sediments incorporate Middle and Upper Palaeolithic stone artefacts, large and small animal remains, coprolites (fossil excrement), marine and terrestrial mollusc shells, as well as charcoal and plant ash which are occasionally concentrated in a manner which suggests they are the remains of hearths. These indicate that the cave was initially occupied over a long period by people who used locally available pebbles and cobbles to make a range of stone tools which falls within the general category of 'Mousterian' and elsewhere (Devil's Tower) are associated with Neanderthal skeletal remains (the well preserved adult Neanderthal skull found at Forbes' Quarry in the North Face in 1848 and originally referred to, before the discoveries in the Neander Valley in Germany, as Homocalpicus, cannot be dated because no details have been preserved of its context). Some flint is known from the Gorham site, which must have been brought or traded from distant sources, possibly even across the straits from North Africa.

The presence of anatomically modern hunter-gatherers during the later Pleistocene is attested by the presence higher in the cave sequence of both large and smallstone blade industries based partially on imported flint. Burnt animal bones exhibiting butchery marks have been found in association with the stone tools throughout the sequence.

Excavation of this site has resulted in the discovery of four layers of stratigraphy. Level I has produced evidence for eighth to third centuries BC use by Phoenicians. Below that, level II produced evidence for brief Neolithic use. Level III has yielded at least 240 Upper Palaeolithic artefacts of Magdalenian and Solutrean origin. Level IV has produced 103 items, including spear-points, knives, and scraping devices that are identified as Mousterian, and shows repeated use over thousands of years. Present day: Access to this cave is at present restricted. Only few personnel are allowed access, obtainable from the Gibraltar Museum, whilst conducting excavations with other relevant bodies.

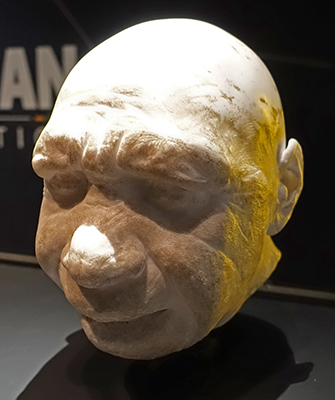

Homo neanderthalensis - skull without mandible from Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar, U.K.

More than 47 000 years old.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Facsimile, Gibraltar 1, Vienna Natural History Museum, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

A recreation of the Neanderthal from Forbes' Quarry.

Forbes' Quarry was the site of the 1848 discovery of the first Neanderthal skull by Lieutenant Edmund Flint of the Royal Artillery. The fossil, an adult female skull, is referred to as Gibraltar 1 or the Gibraltar Skull . Neanderthals were unknown at the time that the fossil was found. Lieutenant Flint, secretary of the Gibraltar Scientific Society, presented his discovery to the organisation on 3 March 1848. Eight years later, in 1856, fossils were discovered in a cave of the Neander Valley near Düsseldorf, Germany. Those remains were described in 1864 as Homo neanderthalensis by Professor William King.

Later that year, the Gibraltar Skull was sent to England and exhibited by George Busk at the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, with its similarity to the Neander Valley fossils noted. However, it wasn't until the early twentieth century that it was realised that Gibraltar 1 was the skull of a Neanderthal. If the skull's significance had been understood in the nineteenth century, Neanderthal Man would probably have been termed 'Gibraltar Man'.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Sculptor: Kennis & Kennis Reconstructions

Source and text: Facsimile, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London

Additional text: Wikipedia

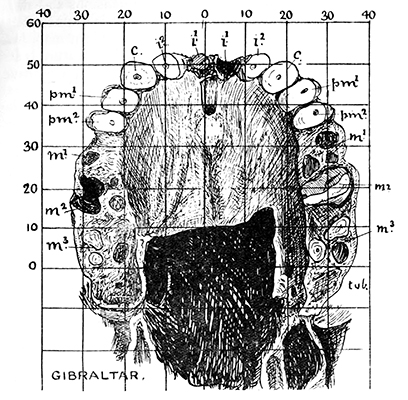

Drawing of the palate of the Gibraltar skull.

Photo: Keith (1915)

Proximal source: archive.org

The openings to Gibraltar caves, including Gorham’s and Vanguard.

Photo: Jaap Scheeren for The New York Times

Proximate source: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/11/magazine/neanderthals-were-people-too.html?_r=0

The interior of Gorham's Cave during the course of John Waechter's excavation, showing a mixture of dark layers of rubbish and clean windblown sand from the beach outside.

Photo from: Man before History by John Waechter.

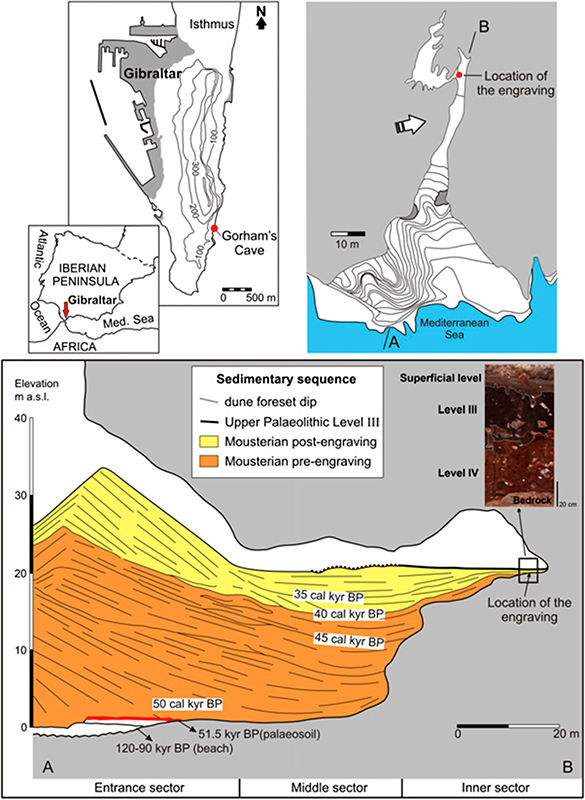

Neanderthal abstract pattern engraving

The first known example of an abstract pattern engraved by Neanderthals has been found in Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar. It consists of a deeply impressed cross-hatching carved into the bedrock of the cave that has remained covered by an undisturbed archaeological level containing Mousterian artifacts made by Neanderthals and is older than 39 000 BP. Geochemical analysis of the epigenetic coating over the engravings and experimental replication show that the engraving was made before accumulation of the archaeological layers, and that most of the lines composing the design were made by repeatedly and carefully passing a pointed lithic tool into the grooves, excluding the possibility of an unintentional or utilitarian origin (e.g., food or fur processing). This discovery demonstrates the capacity of the Neanderthals for abstract thought and expression through the use of geometric forms.

Location of Gorham’s Cave, Gibraltar, in the Iberian Peninsula and schematic map of the Gibraltar Peninsula with altitudes and contours at 100-m intervals (Upper Left), topographic plan of Gorham’s Cave showing the location of the engraving (Upper Right), and interpretative geological section of Gorham’s Cave based on the work of Jiménez-Espejo et al.

(Lower). (Inset) Location of levels III and IV within the general cave sequence.

Photo and text: Rodríguez-Vidala (2014)

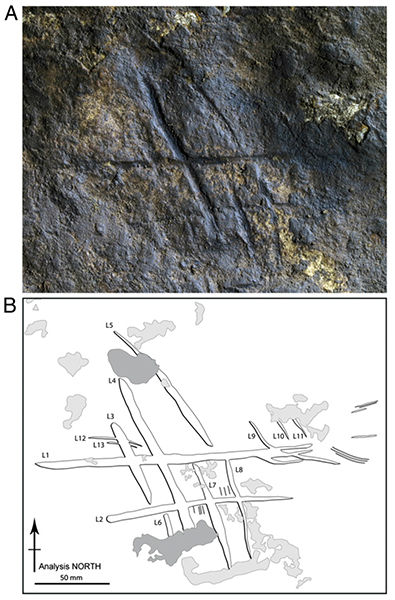

Neandertal Engraving

(A) Engraving from Gorham’s Cave. (B) Engraved lines L1–L13. Dark gray and light gray identify old and recent breaks, respectively.

Photo and text: Rodríguez-Vidala (2014)

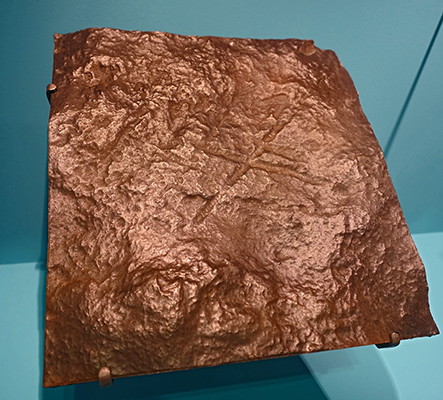

Facsimile of an engraving attributed to Neanderthals, at Gorham's Cave, Gibraltar.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Neanderthals hunted marine mammals

Tuesday, 23 September 2008

by John Pickrell

Home sweet home: Two of the caves in Gibraltar where Neanderthals lived 30 000 years ago.

Animal remains from caves in Gibraltar show for the first time that Neanderthals regularly hunted and fished seafood from mussels and fish to seals and dolphins.

"Up to now we have only had clear evidence that our species, Homo sapiens, exploited marine resources," said Chris Stringer a palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, England. "Now we know that Neanderthals did the same, which provides further evidence of organised foraging and complex behaviour in these close relatives of ours."

Stringer led an international team of researchers who report their research today in the U.S. journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Photo Credit: Clive Finlayson, Gibraltar Museum.

(Note: Gorham's Cave is the one on the left, with the pile of rocks fallen from the cliff above - Don)

View of Gorham's Cave in the east face of the Rock of Gibraltar.

Photo: © Gibmetal77 / Wikimedia Commons

Date: 2007-07-03

Permission: licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence

Butchered bones

The researchers made the discovery by excavating 30 000-year-old fossil material from two coastal caves in Gibraltar, on the southern tip of Span.

Though the caves have not yet yielded actual hominid bones, they have plenty of other evidence that Neanderthals lived there, including the remains of fires for cooking, and numerous stone tools crafted in a style typical of Neanderthals from across Europe.

Alongside the butchered bones of land mammals including wild boar, bear, ibex, red deer and rabbit in the caves the experts also found the bones of young monk seals and bottlenose dolphins.

"The seal bones we found have clear cut marks and peeling, from Neanderthals bending and ripping them from the body to remove meat and marrow," said Stringer, while "the mussel shells had been warmed on a fire to open them."

A recent study of the isotope signatures of Neanderthal bones suggested that these people were much more heavily dependent on red meat than our own ancestors, he said.

Since there is recurrent evidence from several excavated levels over time in both the Gibraltar caves, the researchers believe that eating seafood was not a rare behaviour for Neanderthals at this time. "We have found evidence that they knew the geographic distribution and behaviour of their prey, suggesting they were hunting on a seasonal basis," said Stringer.

Peter Brown, a palaeoanthropologist of the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, said it's great to have more evidence of the diversity of behaviours in human relatives, but that he was "not all that surprised that Neanderthals were smart enough to use adjacent marine resources at Gibraltar."

Brown argued that for both of the marine mammals found in the caves, the numbers are very small, "suggesting a rare opportunity, perhaps scavenging, rather than the regular targeting of species." Young monk seals would have been easy to surprise on the beach, he said, while the dolphins eaten may have been stranded.

Brown noted that Australian Aborigines used to hunt elephant seal on the west coast of Tasmania, which he said is "an order of magnitude more difficult than monk seal." Though these people were our own species, the technology they used was not too different to that used by Neanderthals, he added.

Arcy-sur-Cure

Photo: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham, 1980

Unusual objects collected by the Mousterian occupants of the Hyena Cave at Arcy-sur-Cure in about 35 000 BC. The lump of iron pyrites, the fossil gastropod and fossil coral were all found together.

Sol moustérien de la Galerie Schoepflin, grotte du Renne, Arcy sur Cure, Yonne.

Photo A. Leroi-Gourhan.

Un habitat profond en grotte.

Grotte du Renne à Arcy sur Cure dans l'Yonne:

une habitation avec un sol d'occupation préservé à l'air libre.

Située à plus de 30 mètres de l'entrée, dans une obscurité absolument totale.

Le sol était jonché de milliers de débris osseux et de centaines d'armes et d'outils en pierre taillée.

Le couloir, facile à obstruer, constituait un abri efficace pour se protéger des lions alors assez abondants.

Mousterian deposits of la Galerie Schoepflin, grotte du Renne, Arcy sur Cure, Yonne.

Photo A. Leroi-Gourhan.

A habitat deep in a cave, lying just as it was left.

Located more than 30 meters from the entrance, in total darkness, the ground was littered with thousands of items of bone debris and hundreds of weapons and stone tools.

The corridor is easy to block, and could have been used as a shelter for protection from cavelions at a time when they were quite abundant.

Photo: Don Hitchcock

Source: Photograph on display at the Museum of Chapelle Aux Saints

The Grotte du Lazaret, Nice, France.

The text below is from 'The Prehistory of Europe' 1980 by Patricia Phillips

The text below is from 'The Prehistory of Europe' 1980 by Patricia PhillipsThe Le Lazaret cave contains a sequence of deposits, but the presumed living floor lies in the upper levels. The diagram (after de Lumley, 1969, Une Cabane acheuléene dans la grotte de Lazaret, Fig 54) shows the ground plan of the Le Lazaret 'tent', southern France (inset shows the protected area of the cave)

It dates to the third stage of the Riss glaciation in conventional terms, while aminoacid tests have produced dates c. 150 000 B.P. De Lumley has published detailed distribution maps of the position of stones, flint tools and debris, bone, charcoal and shell, and suggested that the Acheulian hunters created a shelter about 11m X 3.5m at one side of the cave.

The bottom of the shelter wall is defined by rows of stones, including possible post-supports. A skin curtain and roof may have been draped over the posts. The distribution of finds suggested entrances and internal compartments, with two hearths in the larger compartment and none in the smaller. The presence of tiny sea shells, which would have been attached to seaweed, and of the foot bones of fur-bearing animals like wolf, fox, lynx and panther, around the hearth and in the smaller compartment, may indicate bedding. The tools include hand axes and choppers, and lots of tools made of pebbles, of Upper Acheulian type.

Study of the pollen contained in coprolites suggests that the cimate had been colder than today, with stands of pine trees in the vicinity of the cave. The shelter would have provided protection from wind and cold, and represents an attempt to achieve a 'home'.

Molodova

Bed 4 at Molodova I. View of the circular accumulation of mammoth bones.

Photo: © I. K. Ivanova, in Communiqué de presse – 17 janvier 2013, from Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris.

Drawing of a possible arrangement for the hut at Molodova.

Photo: Don Hitchcock

Source: Display at the Museum of Chapelle-Aux-Saints, France

The Prehistory of Europe by Patricia Phillips 1980

Photo: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham, 1980

Photo: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham, 1980

Ground plan of one of the huts at Molodova in the Russian Ukraine, dating to about 42 000 B.C. The objects marked in black represent mammoth skulls. The structure was uncovered at Molodova, near the banks of the Dniester in Ukraine, and enclosed a living space measuring about eight by five meters. The basic framework of this hut was probably of wood covered with skins, which were weighted down at the edge by over one hundred mammoth tusks, skulls, and bones. Inside the hut, diggers uncovered fifteen hearths, many animal bones, and thousands of flint flakes, which indicate a long period of use. Traces of another structure at Molodova also were located a short distance away along the Dniester.

Other open sites are found in Russia. During the Mousterian, nearly all the major valleys of European Russia were occupied, and twenty-three cave sites and ten open sites are known. Two sites at Molodova in Ukraine have Mousterian industries, and are assumed to have been occupied in the Early to Middle Wurm. Molodova lies midway along the Dniester river, and the ancient occupations are contained in colluvium resulting from gravity and hill-wash.

The valley would have been wooded, but cold loving snail species and soil-frost phenomena suggest very cold conditions

Vegetation Zones of Ukraine at the height of the last glacial

Photo: After Klein, R.G. 1969 Mousterian cultures in European Russia. Science, 165, pp. 257-65

Molodova V has minimum carbon-14 dates for the Mousterian levels of > 45 600 BP, > 40 300 BP, and > 35 500 BP. Horizon II of Molodova V (dated > 45 600 B.P.) shows a distribution of cultural remains within an arc of mammoth bones measuring roughly 9 x 7m The arc encloses five hearths, and bone and flint are scattered within it. An even clearer ring of mammoth bones in Horizon 4 at Molodova I has an internal measurement of 8 x 5 m, and contains fifteen hearths and more than 20,000 pieces of flint, plus hundreds of animal bones (Fig. 13). In the same level, sandstone, slate and limestone pebbles were used as grinders and hammerstones. The excavator suggested that the mammoth bones held down skins stretched over a wooden framework. The season of occupation, and length of time spent, is not certain in either case, but Klein suggests the occupations were shorter than in the Upper Palaeolithic (Klein, R.G. 1969 Mousterian cultures in European Russia. Science, 165, pp. 257-65)

Klein believes with the Russians that artifact differences between sites reflect cultural differences, even though some variation may be due to activities carried out at the different sites. Only a few Russian sites have quantified bone reports - Klein's chart for Molodova V mainly indicates the presence of mammoth, for instance, while at Molodova I horse, bison and reindeer also appear. Klein suggests that large herbivores are more common than mammoth in the Dniester river sites, while mammoth are relatively commoner than reindeer and horse on the Dnipro and Desna river terraces. However, only one site in each region has minimum numbers of individuals of the different animal species worked out Vykhvatintsy and Kodak respectively). Given the limited faunal data, it is unclear how far Mousterian groups concentrated on single species or a few species, although the data from Érd and a few other central European sites seem to indicate specialization on cave bear, while reindeer are preponderant at Salzgitter-Lebenstedt in Germany, and mammoth at the Prut valley site of Ripiceni-Izvor.

In all nearly 200 individuals are known from the Middle Palaeolithic sites. This is mostly because of the increase in the practice of burial in the Middle Palaeolithic. For instance, at the Guattari cave, Monte Circeo, Italy, a Neanderthal skull was found lying in the middle of a circle of stones. An artificial hole had been punched at the base of the cranium. In the same level were remains of red deer, cattle, horse and hyena; the presence of naturally dropped red-deer antler suggests the autumn as the time the cave was used. The Ehringsdorf skull also had a depressed fracture, and thirteen skeletons are believed to have been part of a cannibalistic feast at Krapina. It seems possible that killing and cannibalism occurred (Roper, M.K. 1969. A survey of the evidence for intrahuman killing in the Pleistocene. Curr. Anthrop., 10, 4, pp 427-59), and the statistical evidence correlating the behaviour towards human skeletal remains with that towards animal fauna at the Hortus cave is relevant in this connection.

References

- Keith, A. , 1915: The Antiquity of man, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott company; London: Williams and Norgate

- Leroi-Gourhan, A., 1950: La grotte du Loup, Arcy-sur-Cure (Yonne), Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, Année 1950 47-5 pp. 268-280

- Rodríguez-Vidala, J. et al., 2014: A rock engraving made by Neanderthals in Gibraltar, PNAS, Published online before print September 2, 2014, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411529111 PNAS September 2, 2014.