Altamira Cave Paintings

Altamira Cave Entry

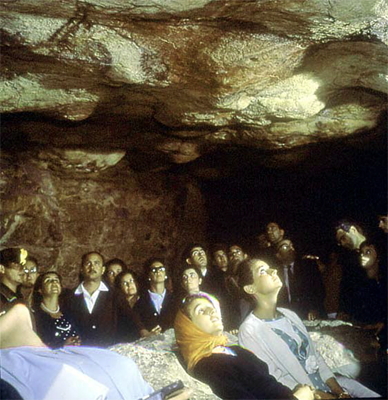

Photo: Guinea (1979)

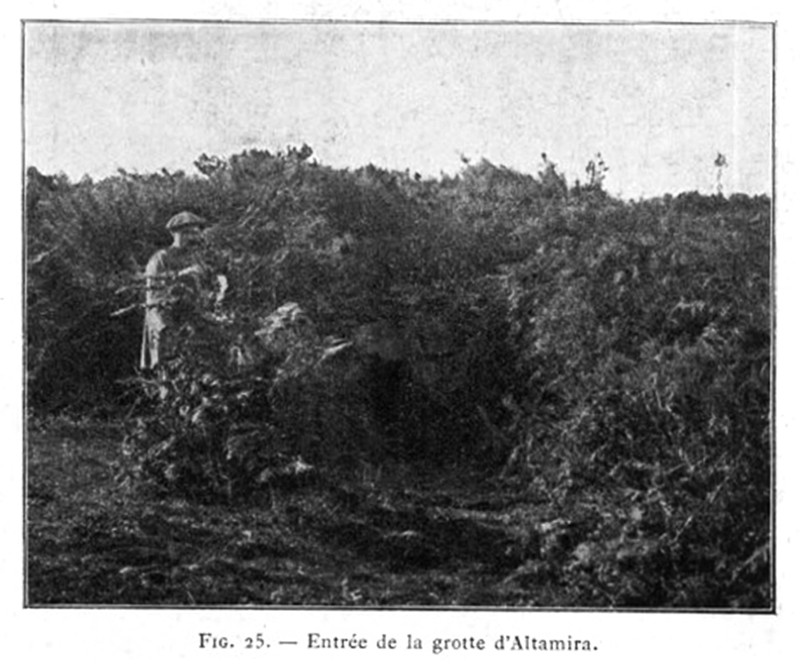

When the cave was discovered in 1868 by Modesto Cubillas Pérez, share cropper on Don Marcelino S. de Sautuola's estate, the cave was almost completely hidden by the undergrowth accumulated over thousands of years, and the rubble of stones at the entrance made access difficult, and difficult even to see. It was only while detaching a dog who had gotten stuck in the entrance that Cubillas Pérez saw it.

Today the original wider mouth of the cave has been closed off by a wall, into which a double metal door has been built, with the necessary ventilation holes to permit normal air circulation, with a locked metal grille on the outside.

Text: Guinea (1979)

Altamira Cave Entry

Photo: albertoyp via Panoramio

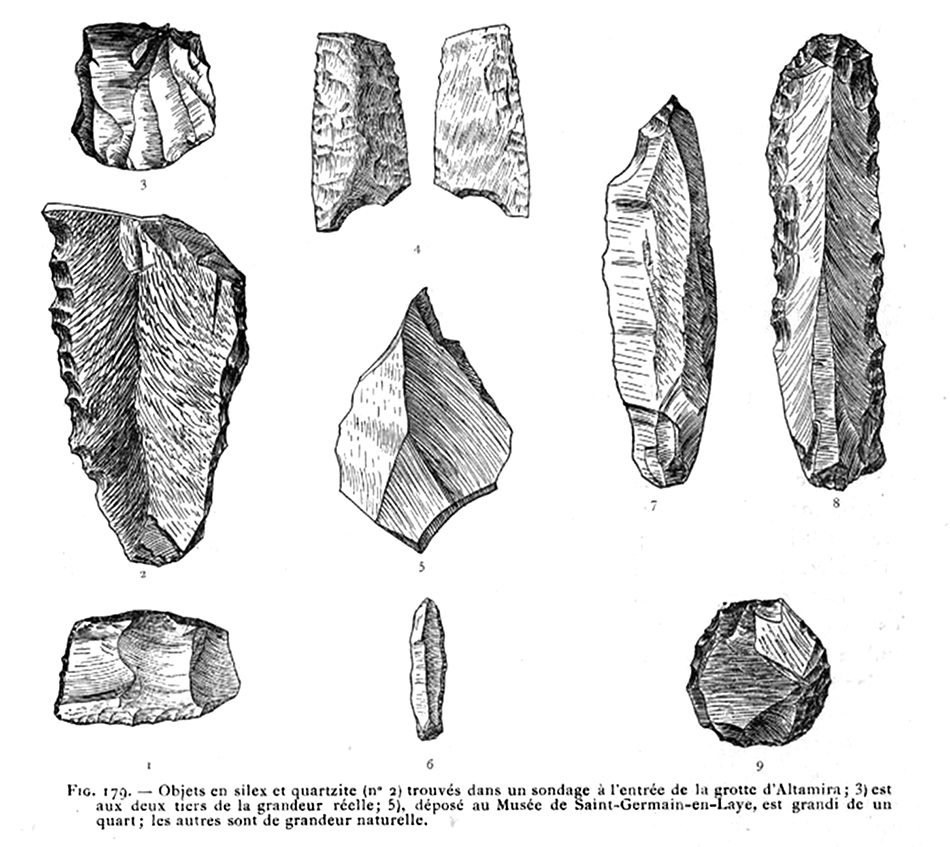

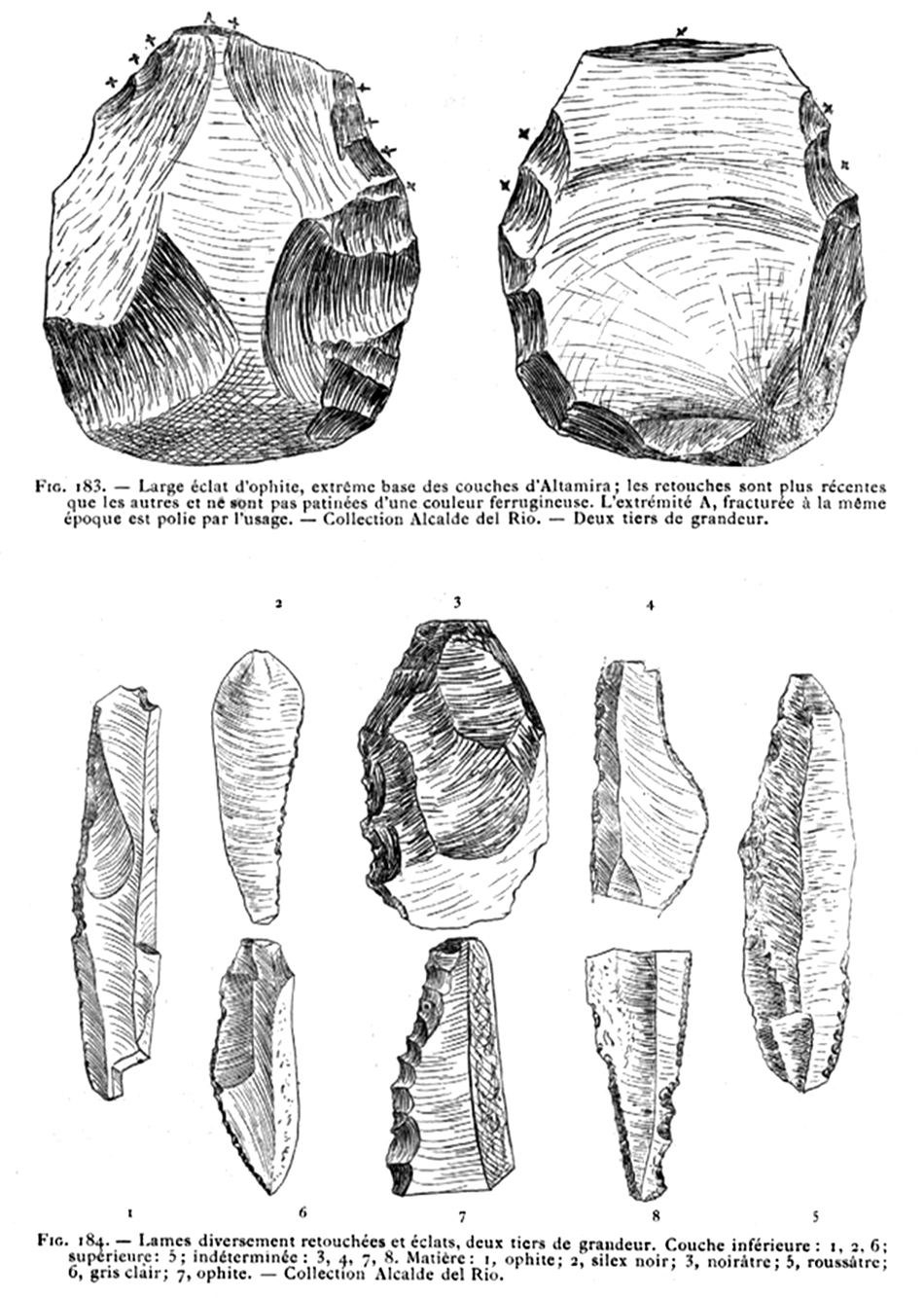

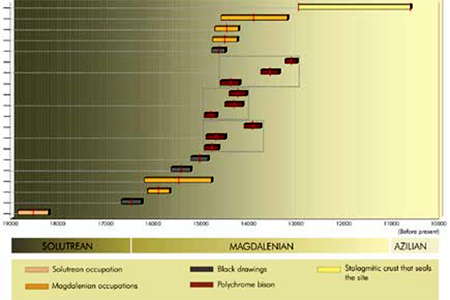

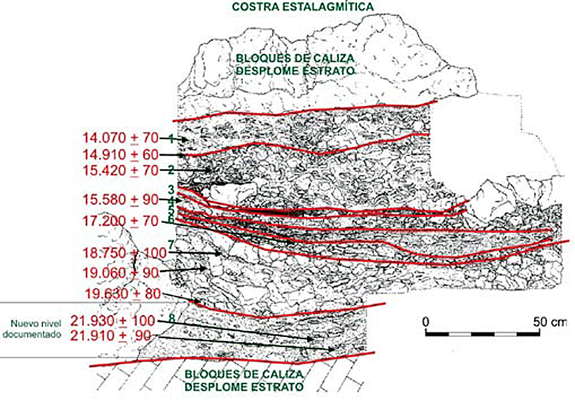

Altamira Cave is 270 metres long and consists of a series of twisting passages and chambers. The main passage varies from two to six metres in height. Archaeological excavations in the cave floor found rich deposits of artefacts from the Upper Solutrean (ca 18 500 years ago) and Lower Magdalenean (between ca 16 500 and 14 000 years ago). Both periods belong to the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. In the millennia between these two occupations, the cave was evidently inhabited only by wild animals. Human occupants of the site were well-positioned to take advantage of the rich wildlife that grazed in the valleys of the surrounding mountains as well as the marine life available in nearby coastal areas. Around 13,000 years ago a rockfall sealed the cave's entrance, preserving its contents until its eventual discovery, which occurred after a nearby tree fell and disturbed the fallen rocks.

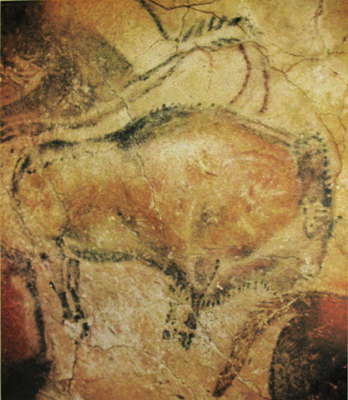

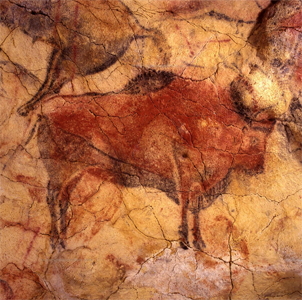

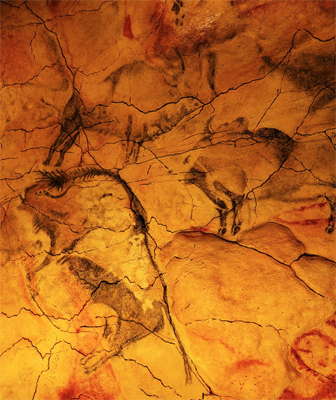

Human occupation was limited to the cave mouth, although paintings were created throughout the length of the cave. The artists used charcoal and ochre or haematite to create the images, often diluting these pigments to produce variations in intensity and creating an impression of chiaroscuro. They also exploited the natural contours in the cave walls to give their subjects a three-dimensional effect. The Polychrome Ceiling is the most impressive feature of the cave, depicting a herd of extinct Steppe Bison (Bison priscus) in different poses, two horses, a large doe, and possibly a wild boar.

Dated to the Magdalenean occupation, these paintings also include abstract shapes in addition to animal subjects. Solutrean paintings include images of horses and goats, as well as handprints that were created when artists placed their hands on the cave wall and blew pigment over them to leave a negative image. Numerous other caves in northern Spain contain Palaeolithic art, but none is as complex or well-populated as Altamira.

Text above adapted from Wikipedia.

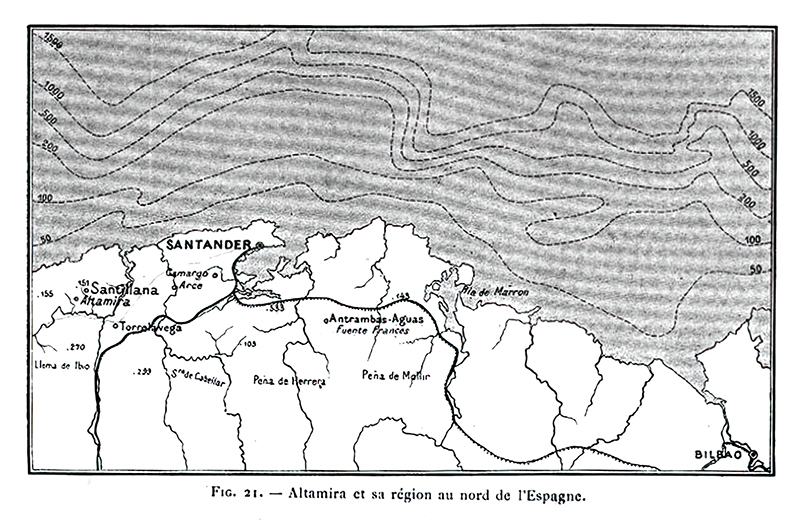

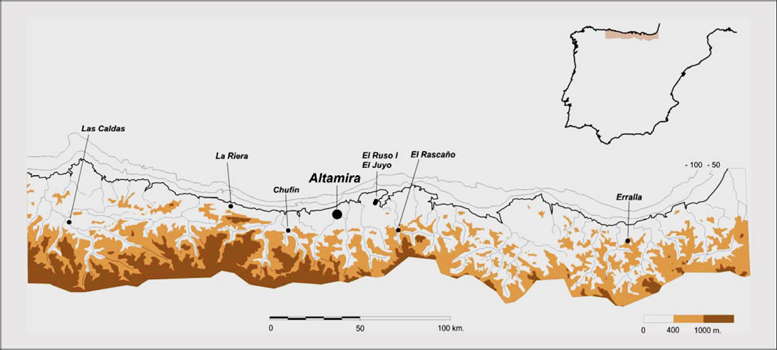

Altamira and its region in the north of Spain.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

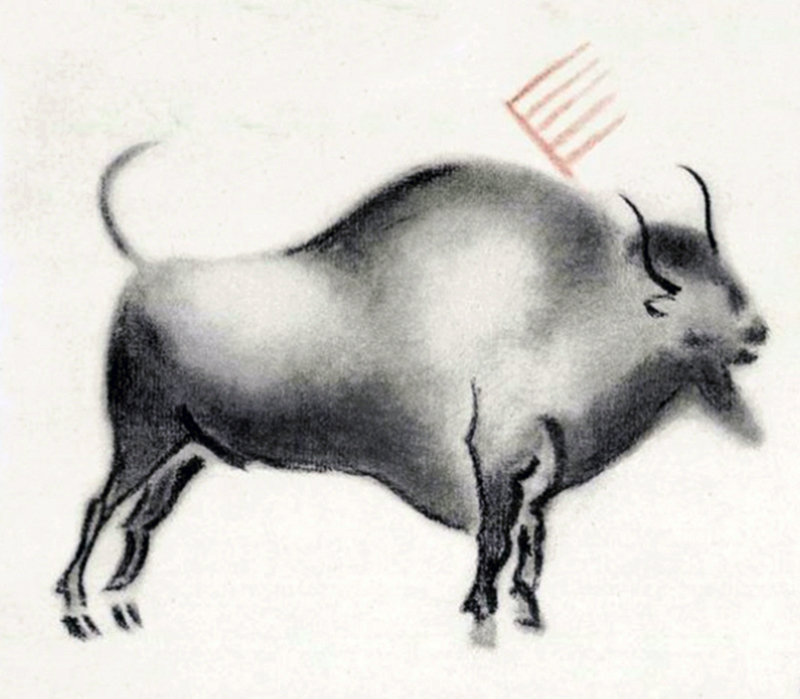

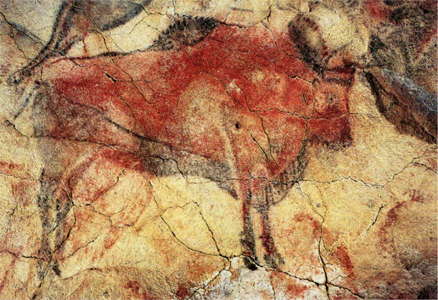

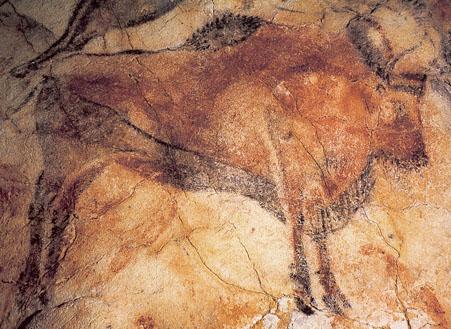

One of the bisons on the ceiling of Altamira in Spain, representing the final stage of polychrome art in which four shades of colour are used.

Photo: M. Burkitt 'The Old Stone Age' (1955), after Breuil.

Bison at Altamira. This appears to be the original of the one that Breuil painted, above.

Photo: Original, Leroi-Gourhan (1992)

Another version of the bison above.

Photo: Guinea (2011)

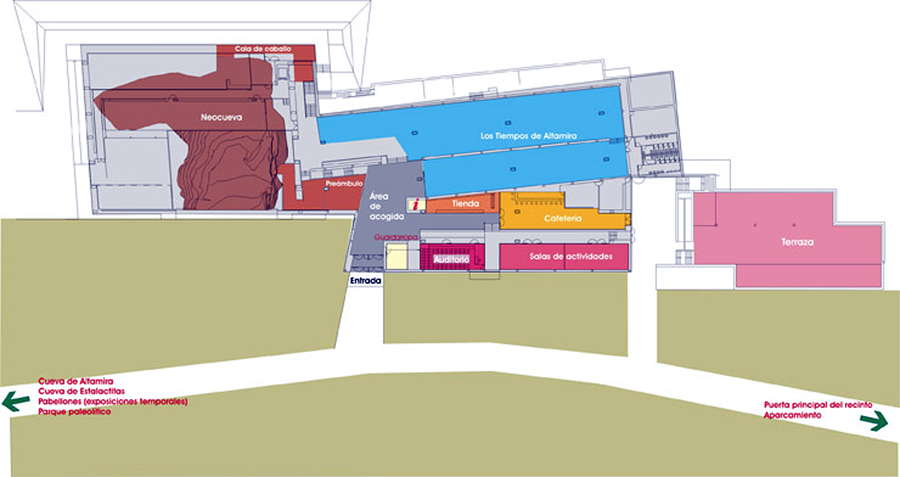

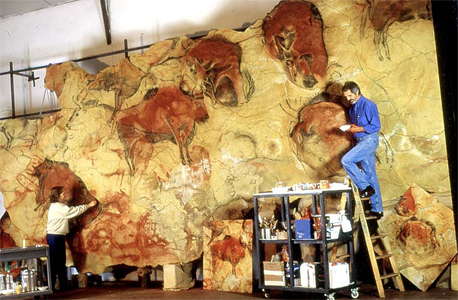

The 'Neocueva', part of El Museo de Altamira, which aims to recreate the environment at Altamira so that people may get a feeling for the life of the people of Altamira, while the original cave is kept from harm.

The large size of the mouth of the cave (20 metres wide and 6 metres high) provided access to a large 'hall'. This large covered entrance lasted until 13 000 years ago, when it collapsed, sealing the cave, until it was discovered in 1868 when a hunter's dog chased a fox across hilly countryside. The dog fell among some boulders. When the hunter rescued the dog, he saw the entrance to a cave.

Illuminated by daylight, this was the place where the tribe lived.

Photo and text: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

Plan of the Altamira museum, showing the display areas and the Neocueva. Note that North is towards the bottom of the image.

Photo: http://museodealtamira.mcu.es/ingles/exposicion_museo_00.html

Aerial image of the museum and Altamira Cave, which is circled.

North to the top of the image.

Photo: Google Earth

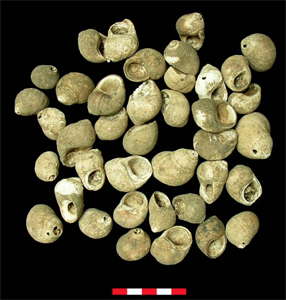

Because the inhabitants lived close to the coast, fish was a common part of the diet. One of their regular activities was to organise expeditions to the coast to spear or cast their nets to catch fish from the sea.

Shellfish are also abundant on the coast. They obtained abundant seafood as well as highly prized shells, which according to their size were used as containers, decorative objects for the body, or ritual magic.

Photo and text: www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

Female bison at Altamira. This is a reproduction in the 'Deutsches Museum', Munich.

Photo: Ramessos

Permission: Public Domain

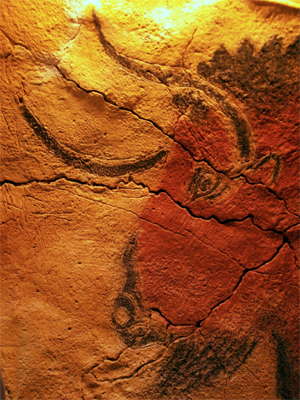

Head and forequarters of the bison above.

Photo: Guinea (2011)

Another version of this female bison.

Photo: (left) Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

(right) Gallup et al. 1997

Another version of this female bison.

Photo: http://coursecontent.westhillscollege.com/Art%20Images/CD_01/DU2500/index.htm

The ceiling art does not conform to any alignment or proportion of size, and some images overlap others.

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

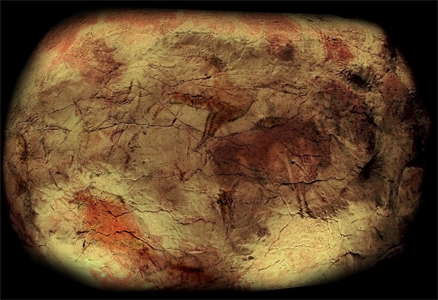

Altamira ceiling.

Photo: http://www.arretetonchar.fr/

Bison. Time has faded this image.

Photo: Guinea (2011)

Head of a bison. This is an excellent photograph from the display at the Altamira Museum, and shows the care and attention to detail of the artists commissioned to make copies of the original Altamira paintings.

Photo: Ernesto Lazo via Picasa

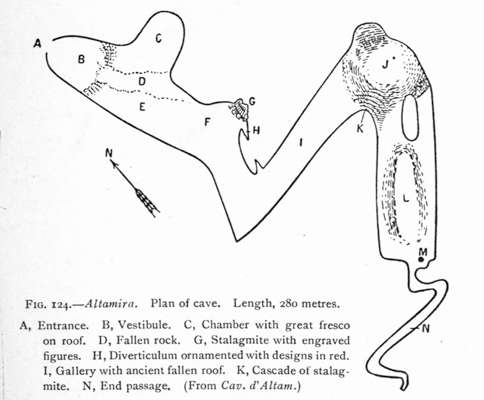

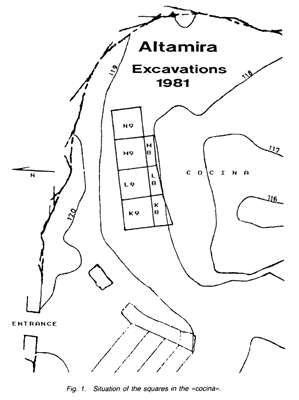

Plan of the cave at Altamira.

Photo: Nachosan

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution Generic / Share-Alike 3.0

Plan of the cave at Altamira.

Photo: E. Pfeiffer 'The Creative Explosion'

Altamira cave has three main galleries: the Chamber of the Frescoes ("Gran Sala de los Policromos" or "Sala de los Frescos"), the Chamber of the Hole/Basin/Pit ("Sala de la Hoya") and the end passage known as the Horse's Tail ("Cola de Caballo").

Plan of the cave at Altamira.

Photo: Parkyn (1915) (Public Domain)

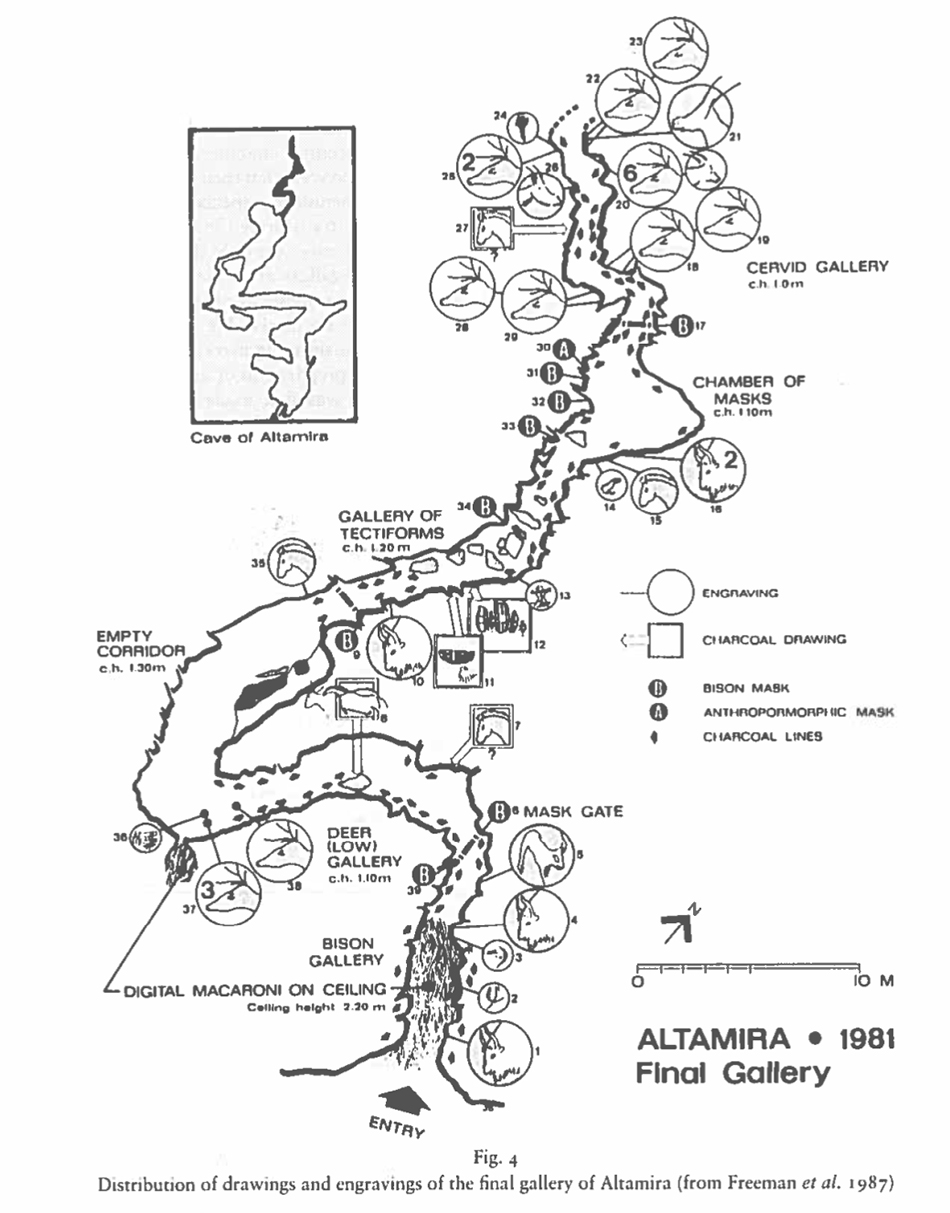

Distribution of drawings and engravings of the final gallery of Altamira.

Source:Freeman et al. (1987)

Proximal source:de Quirós (2014)

Altamira cave is set on a hillside, and there is little to tell the casual traveller what mysteries lie behind the trees.

Photo: Hans Castorp via Panoramio

The cave is not open to the general public.

Photo: ProfBoss via Panoramio

View of the mountains from Altamira, which means 'high view'.

You can see why, when you look at this photo of the vista of the Picos de Europa mountains from outside the cave of Altamira, with the ground you are standing on just above the polychrome chamber.

Photo: Saura Ramos et al. (1999)

This photo was taken in the original cave in the 1970s.

Photo: Corruchaga et al. (2003)

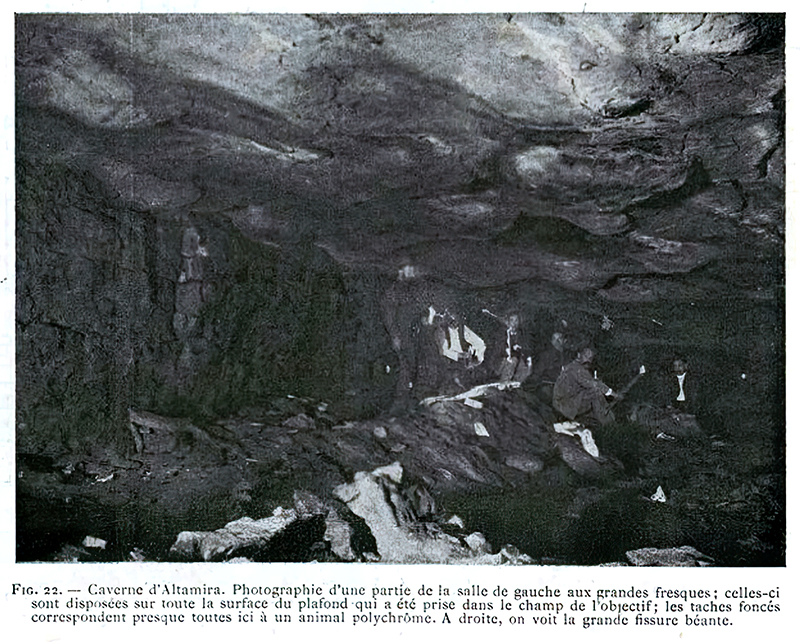

Figure 22

Cave of Altamira. Photograph of part of the left-hand room with the large frescoes; these are arranged over the whole surface of the ceiling which was taken in the field of the lens; the dark spots almost all correspond to a polychrome animal.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Figure 25

Entry to the cave circa 1906.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

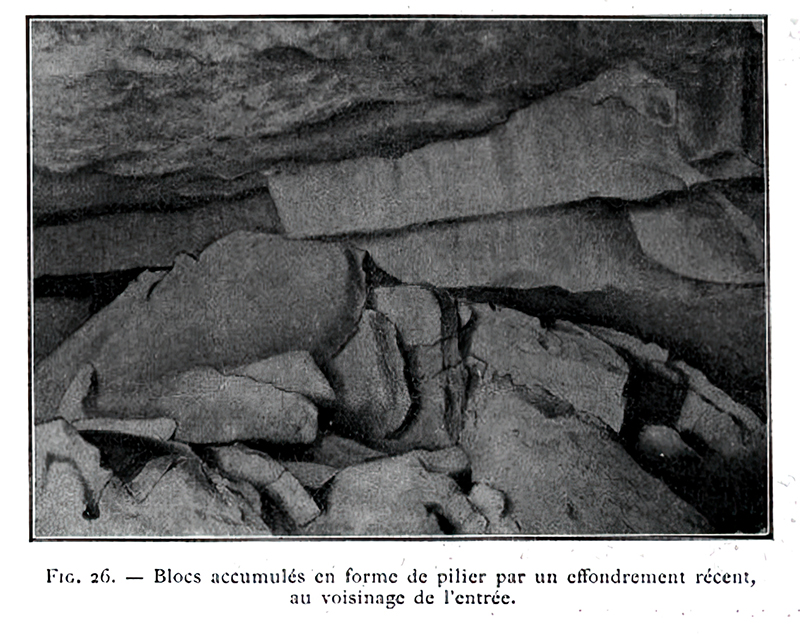

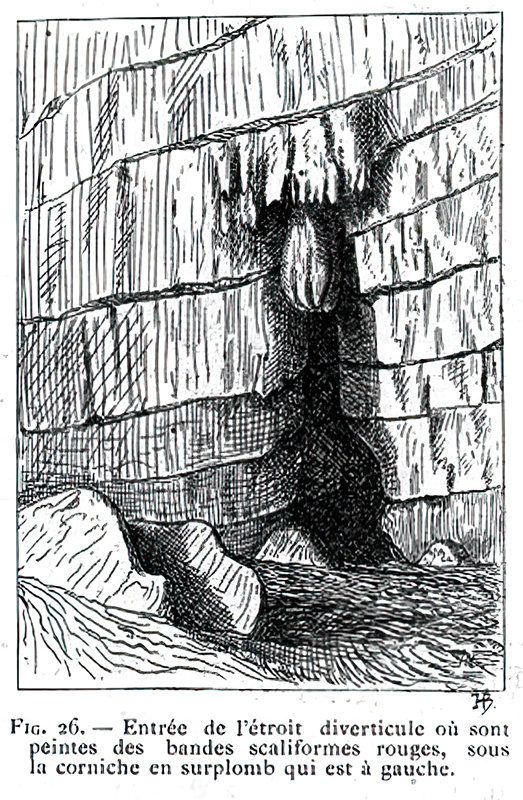

Figure 26

Pillar-shaped blocks accumulated by a recent collapse in the vicinity of the entrance, circa 1906.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Interior of the cave of Altamira. The geological structure favours the collapse of layers of rock which leaves a horizontal ceiling and angular features in the wall.

Photo: Lasheras (ca 2008)

View of the Altamira site, with a dig in progress.

Photo: © Pedro Saura Lasheras (ca 2008)

Figure 26

Entrance to the narrow diverticulum where red scaliform ( ladder shaped - Don ) bands are painted, under the overhanging cornice on the left.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

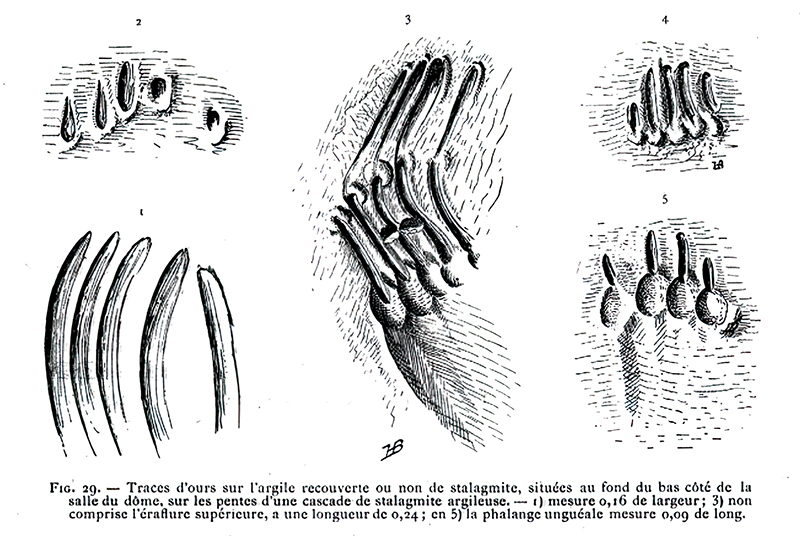

Figure 29

Bear tracks on stalagmite-covered and non-stalagmite-covered clay, located at the bottom of the lower side of the dome room, on the slopes of a clay stalagmite cascade.

1) measures 16cm wide; 3) not including the upper edge, is 24 cm long; 5) the ungual phalange measures 9 cm long.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

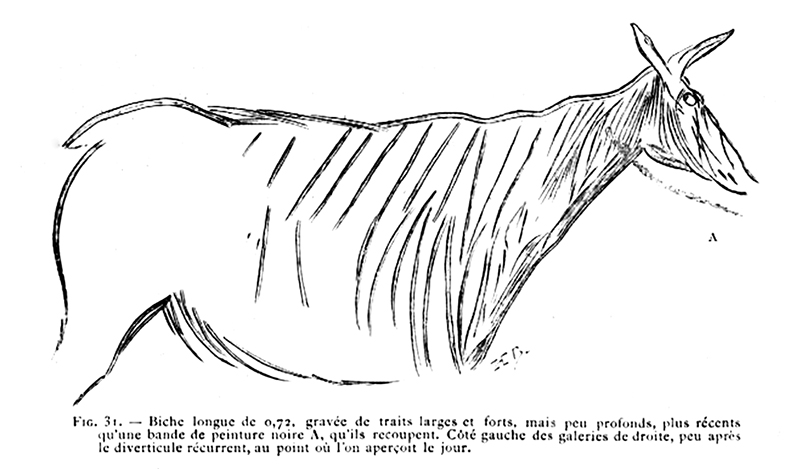

Figure 31

Doe 72 cm long, engraved with broad, strong, but shallow strokes, more recent than a strip of black paint A, which they intersect. Left side of the right-hand galleries, shortly after the recurrent diverticulum, at the point where the daylight can be seen.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Bison.

Photo: Guinea (2011)

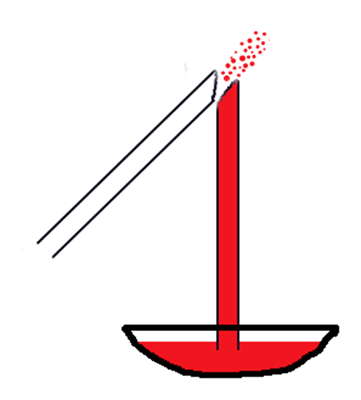

Many of the paintings at Altamira appear to have been airbrushed, a sophisticated technique which may be done as shown. Two hollow bones are used, one set perpendicularly in a container of water and ochre, the other is held in the mouth.

When the artist blows across the open hollow bone, the reduction in air pressure forces the ochre up the vertical hollow bone, at which point it is blown onto the rock surface by the jet of air from the bone held in the mouth of the artist.

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

It may even have been possible to airbrush paintings on the ceiling using this method, with a little ingenuity.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2012

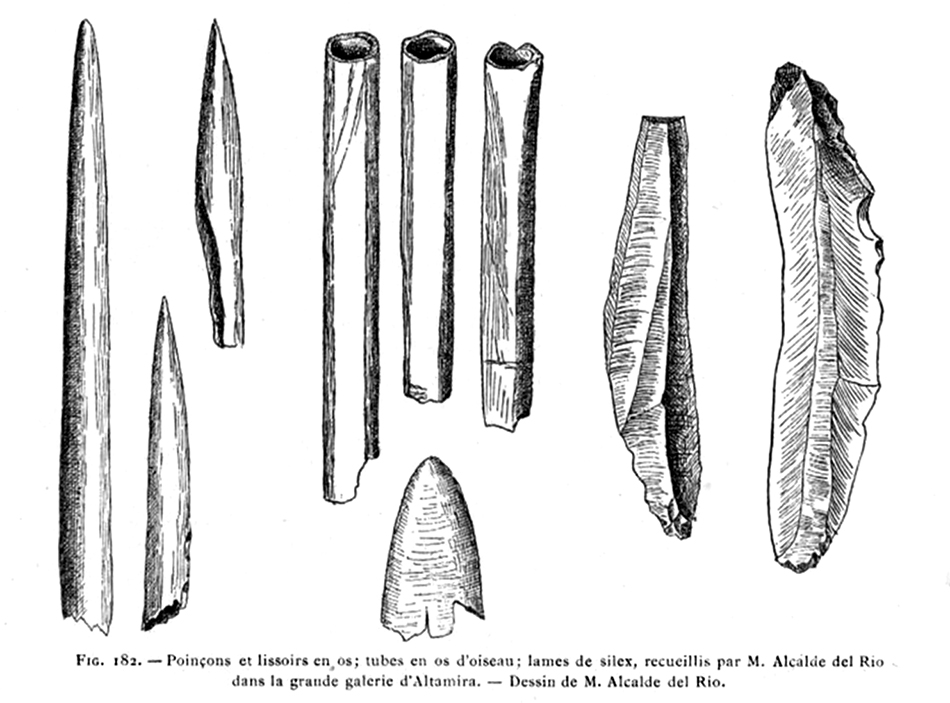

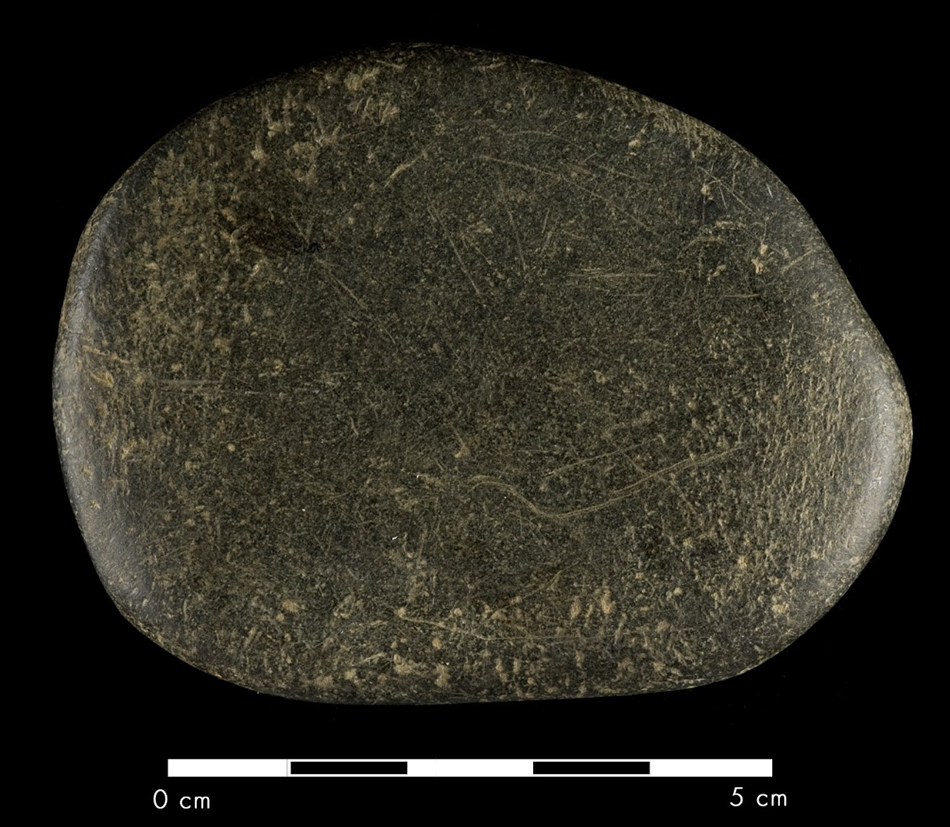

Airbrush from Altamira

22 000 - 13 500 BP.

Wing or leg bone of a bird (a bird of prey or wader) cut in half to create hollow tubes of the same size, used to blow a spray of paint droplets.

Length: 55.50 mm

Width: 7.64 mm

Thickness: 7.21 mm.

Photo: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

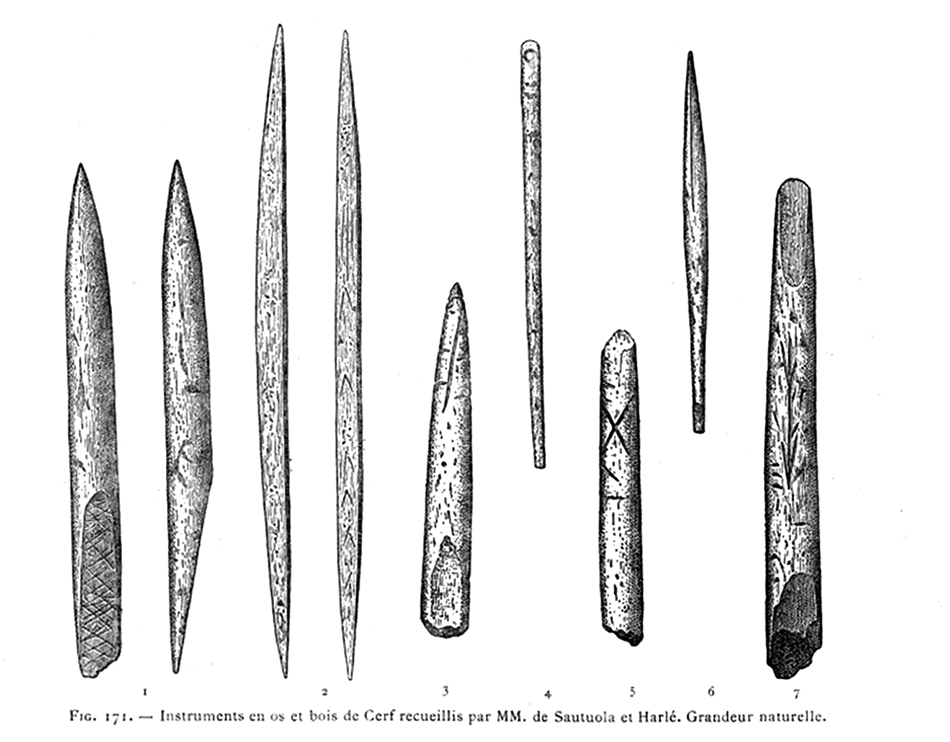

Bone sewing needles from Altamira

13 500 - 11 000 BP.

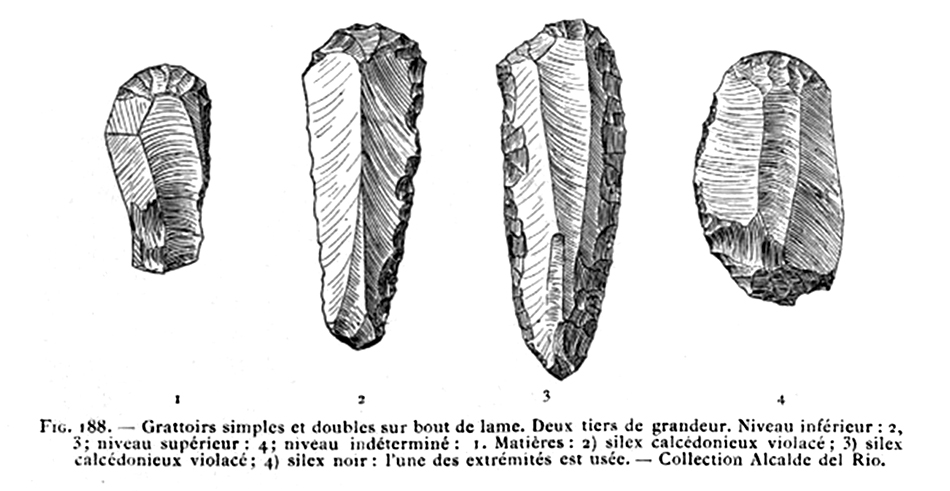

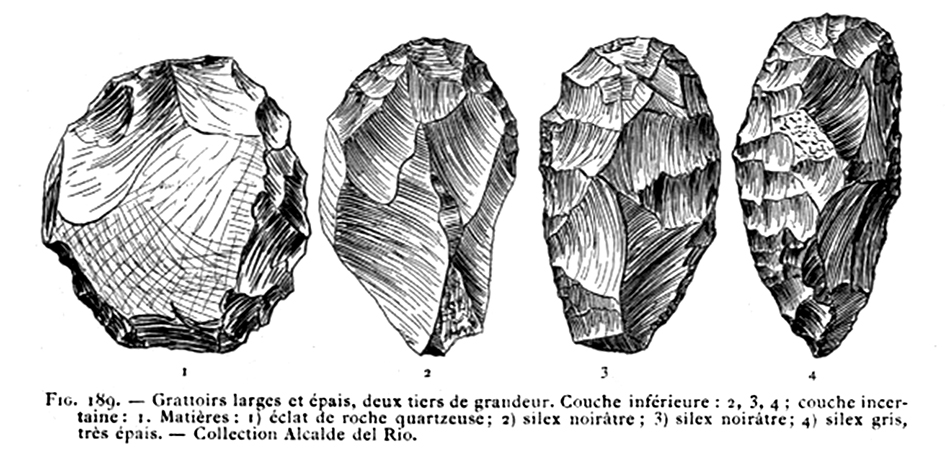

This Palaeolithic invention had the same purpose as the current tool: to make clothes, shoes or hats. With parallel grooves made with a burin, thin rods were extracted from the bone which later were perforated and polished on stone to make needles. The smallest ones, with a 2 mm diameter and an eye, prove how well they tanned skins to make clothes, and how thin the thread was, which was probably made of animal tendon.

Photo: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

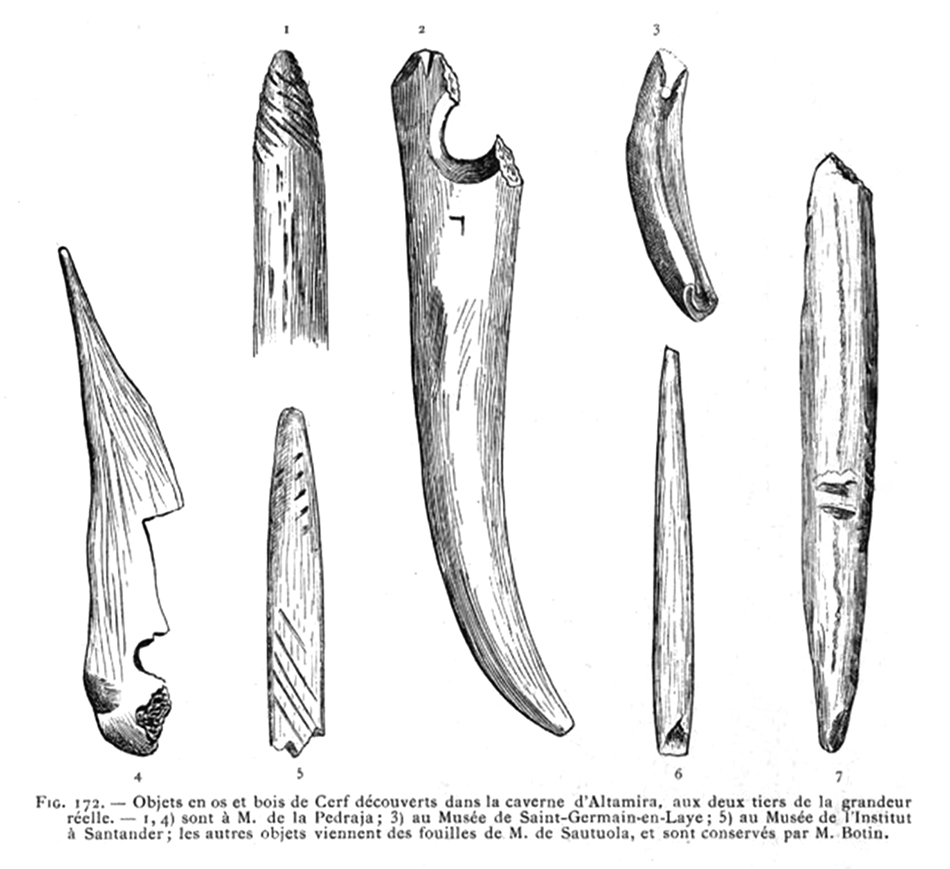

Antler harpoons from Altamira, during the Magdalenian era. Used to catch fish, especially salmon, and perhaps to hunt other animals as well. Made of deer antler, with either one or two rows of teeth. Different types of spears were developed to attach these points to, and different ways of attaching them were developed as well.

Note the hole in one of them, this was used to attach a cord so that when the harpoon detached from the spear, the fish could still be hauled in.

The simplified designs with one row of teeth was made on the flat side of a large bone, and were easier and faster to make, and just as effective.

13 500 - 11 500 BP.

Photo and text: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

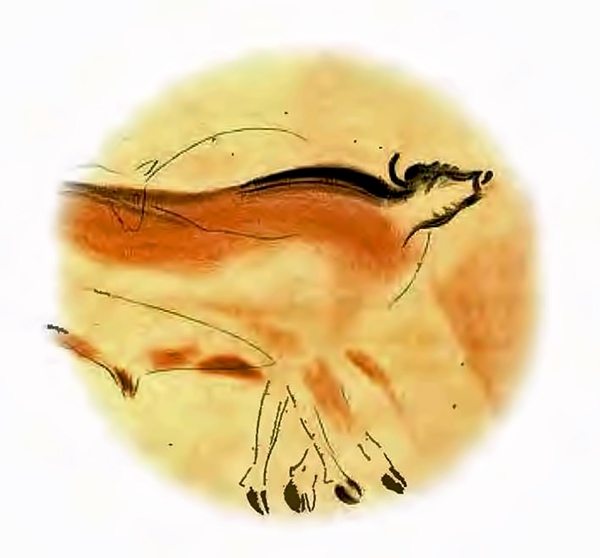

This is the best example of making the most of the support and natural materials when painting on Palaeolithic caves.

This bison, apparently lying on the ground, or leaping forward in a magnificent charge against an adversary was painted using a natural bump in the ceiling. The cracks on the wall were used to outline its head and body, forcing its posture a little, with the head between the front legs.

This technique which involves making the most of the natural support is quite similar to what important 20th century avant-garde artists would do later on.

( I think of this as the 'Leaping Bison', but the reality is more prosaic. The bison often made hollows or dips in the ground which filled with water, where they rolled around and wallowed in the mud they created, in order to rid themselves of troublesome insects.

See de la Campa et al. (2001) - Don )

Photo and text: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

Another version of this wonderful work.

Photo: http://coursecontent.westhillscollege.com/Art%20Images/CD_01/DU2500/index.htm

The same bison, showing some of the other paintings crowding the ceiling.

Photo: Photo: Guinea (1979)

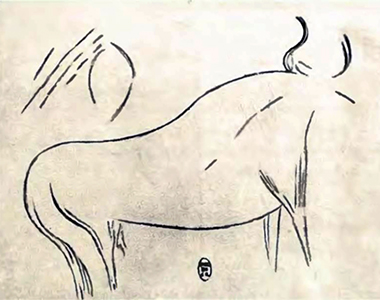

Drawing of a bison sent by Sautuola to E. Piette in 1887.

Photo:

de la Campa et al. (2001)

Black bull in motion.

Painting: Breuil and Obermaier (1935), Illustration X.

Proximate source: de la Campa et al. (2001)

Detail of the ceiling, with red claviform signs, a horse, and engravings of huts.

Painting: Breuil and Obermaier (1935), Illustration VI.

Proximate source: de la Campa et al. (2001)

Head of a bison in black.

Photo: http://www.cuevamuseoaltamira.com/

Bison.

Photo: Guinea (2011)

BIson, another version of the one above.

Photo: http://grupos.unican.es/Arte/Ingles/prehist/paleo/b/Default.htm

Black bison. This has been drawn with charcoal, just as modern artists do. The carbon 14 dating gives a date of 13 000 BP, which is just before the cave collapsed, sealing it until modern times.

After drawing with charcoal, the lines were smudged to give the figure volume on the hump and belly, but with a firm and intense stroke on the front legs.

Photo: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/ © Pedro Saura

View of the ceiling of the 'Paintings Chamber'.

Photo: de la Campa et al. (2001)

Handprints were created by blowing ochre mixed with water over the hands, leading to the effect shown here.

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

This handprint was obtained by smearing ochre and water on the hand, and then pressing it on the wall. Both techniques were widely practised by ice age hunters.

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

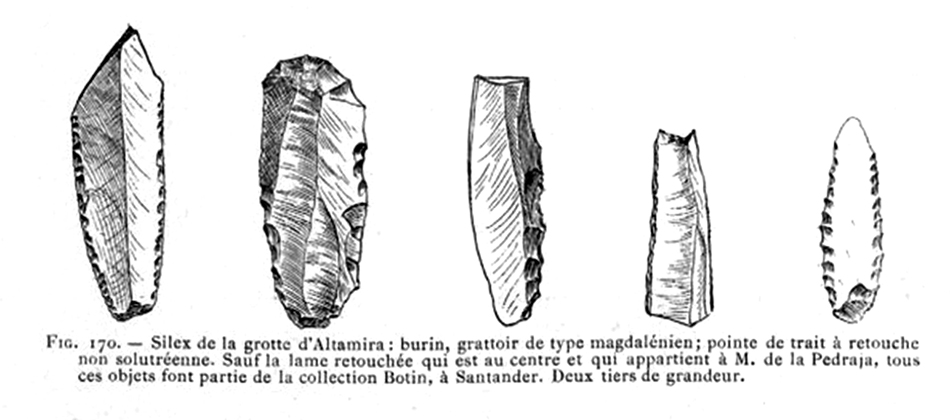

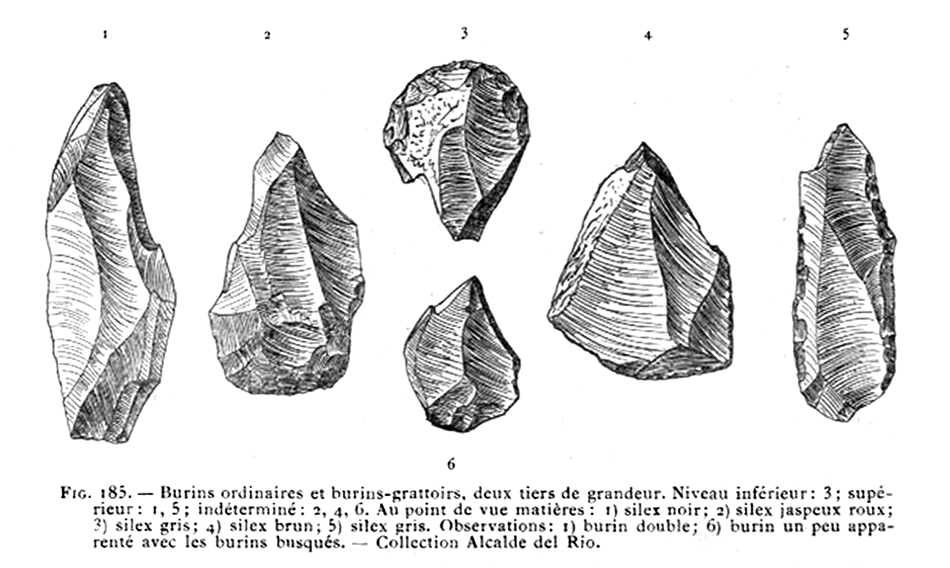

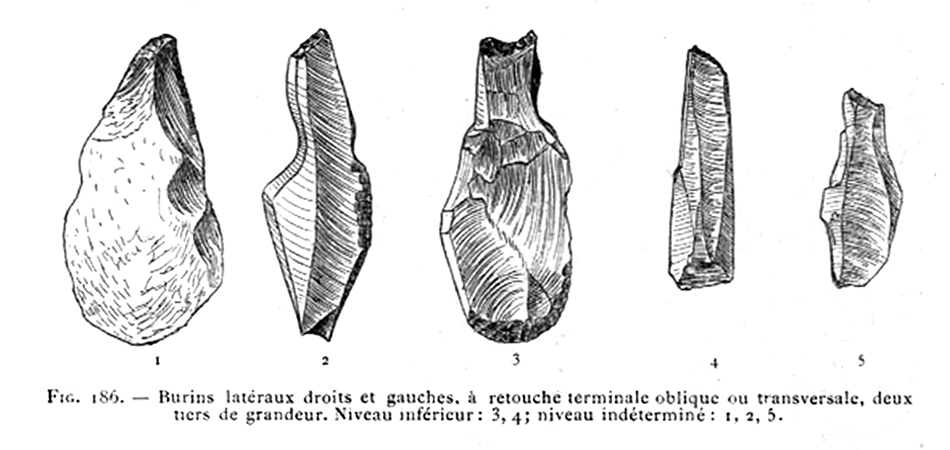

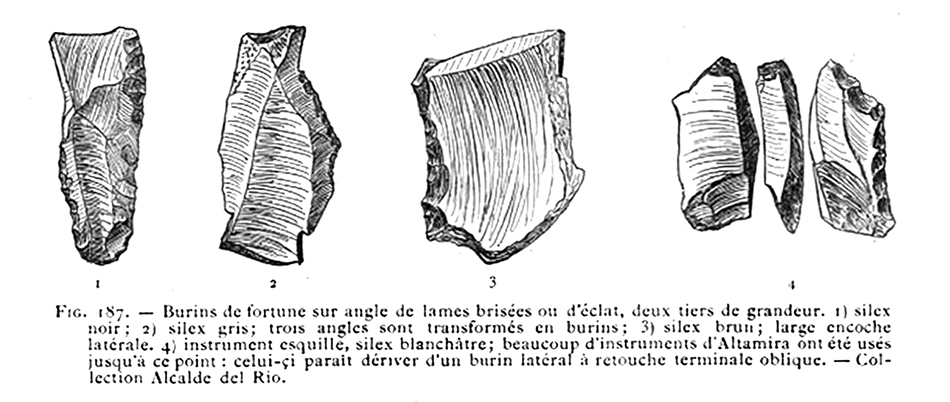

Burins from Altamira.

The burins were made on flint flakes, with the end truncated to get a sharp, chisel like point. They were used to engrave limestone, bone, or antler.

For bone, a deep groove was made, which was gone over again and again with the burin until a thin rod could be extracted to make a point for a spear or a long thin piece of bone for a needle. They were also used to engrave art works on tools and other objects, and to engrave the outlines of animals on cave walls before infilling with ochre and charcoal.

Photo: National Museum and Research Center of Altamira © Ministry of Culture

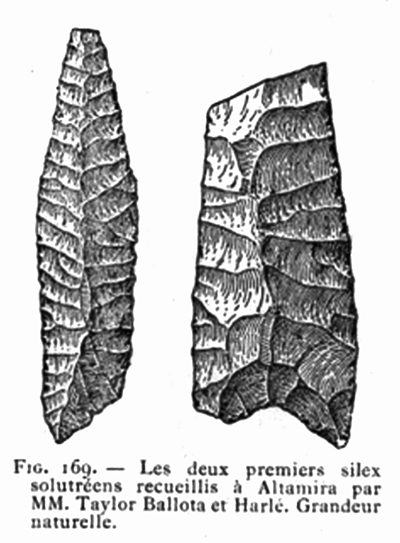

Flint spearhead. The shape and technique of pressure retouch stamps this as being from the Solutrean. The flint was probably heat treated to facilitate the pressure flaking. The entire surface has been retouched. The base on the left appears to have been worked into a shouldered or tanged shape to make attachment to a spear shaft easier.

(Note that the tip on the right of the spear head has been broken off. It would originally have come to a superbly finished point at the end. The hunter must have been sad to see such a beautiful piece ruined. Making a superb piece of work like this required high skill and a lot of time - Don )

Dimensions:

Length 62.41 mm, width 19.30 mm, thickness 6.13 mm.

Date: 18 500 BP

Photo: © Pedro Saura, Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

During the Upper Palaeolithic, spearheads attached to a shaft which could be thrown with the hand or with a spear thrower or atlatl were often made of deer horn. Bone and antlers are tough, and have a long life, even though they are not as sharp as a flint point. During the Magdalenian era (the last cultural period of the Upper Palaeolithic) they were the main instrument used to hunt animals, although the systems to attach them onto a shaft changed over time.

The base, with bevelled edges, would be used to fix the head onto the wooden shaft. The engraved marks would enable a better grip for adhesion of the resin or glue mixture used to join the piece to the wooden part, and would be reinforced with cord made of plant fibres or tendon. Like harpoons, they sometimes had engraved decorations or signs.

Date: 16 000 BP - 14 000 BP

Photo: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

This flint point, carved in the shape of a willow leaf, belongs to the Solutrean period of the upper Palaeolithic era. The piece is finely flaked in order to obtain a symmetrical shape similar to a willow leaf. It would have been attached to the end of a wooden shaft by means of resins and vegetable or sinews and then used as a projectile weapon.

The shape of this type of point, together with the details of its flaking techniques, offer clues to its chronology and the specific cultural and territorial context to which it belongs.

Dimensions: length 79 mm, width 22 mm, thickness 7 mm

Date: 22 000 BP - 14 000 BP

Photo: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

Head of a deer. This image is not in the same room as the polychromatic bison on the main ceiling, but in a chamber deeper in the cave.

The head has been outlined in black, without any further shading.

Photo: Guinea (2011)

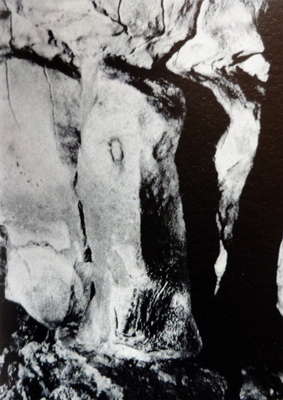

This face is only seen after going to the end of the cave, and starting back.

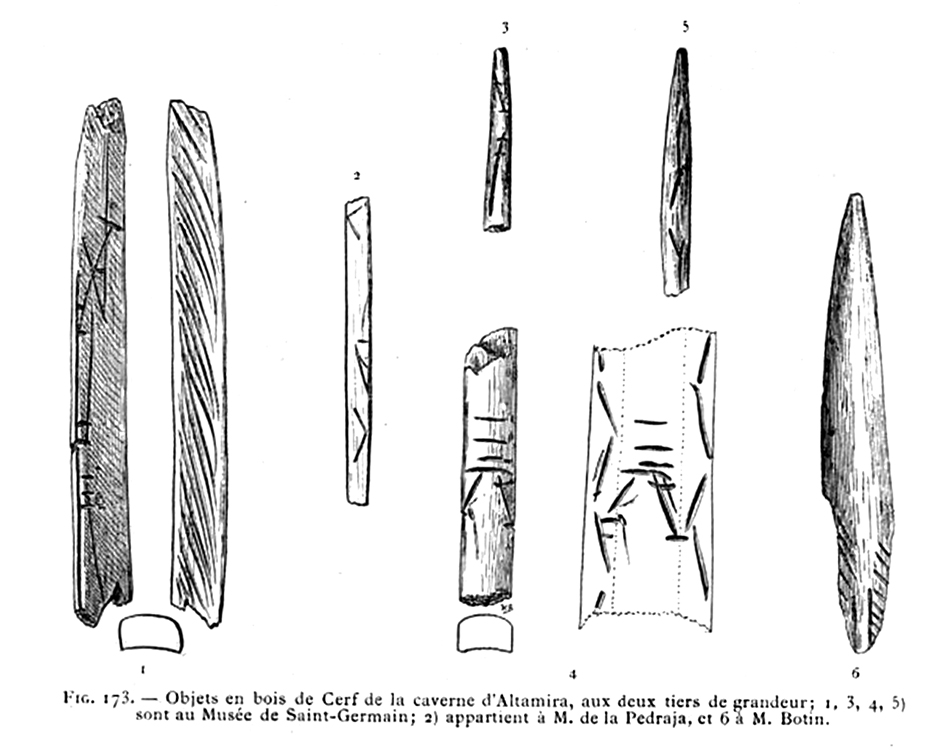

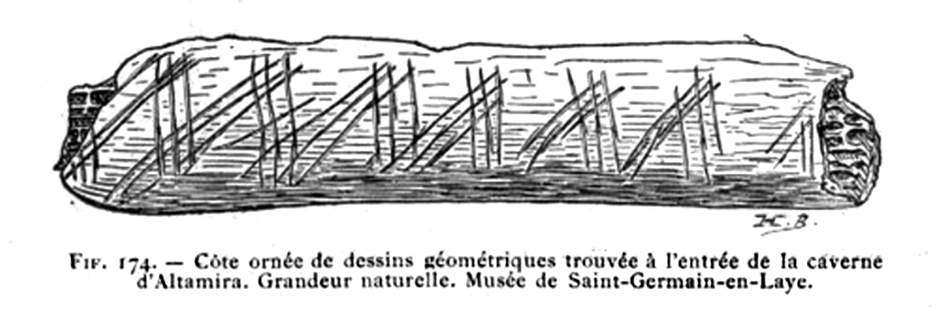

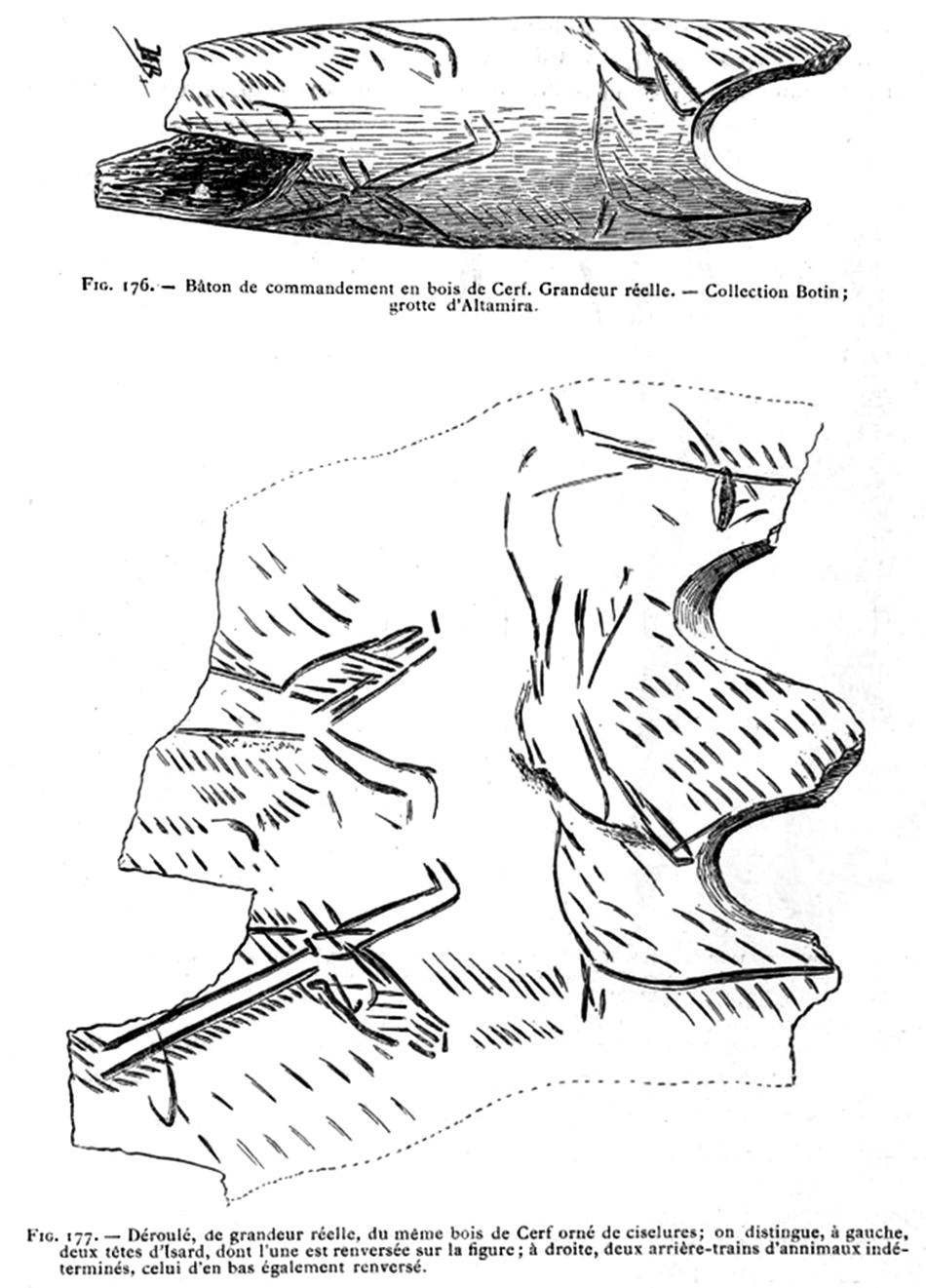

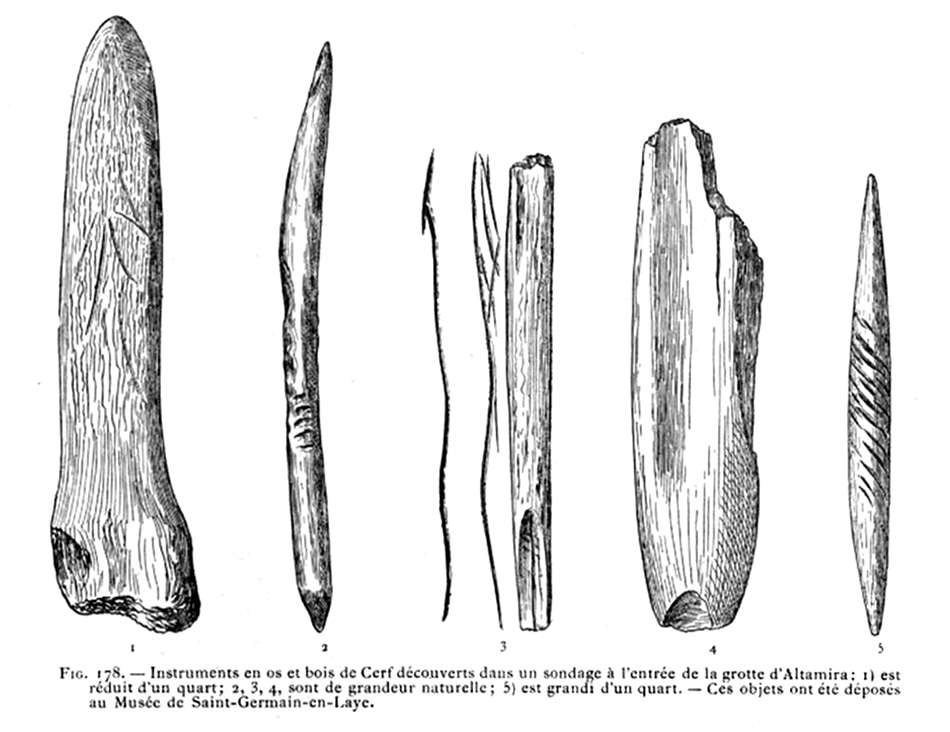

It looks like a natural feature of the walls, but was known to the painters, and no doubt had great significance.

One 'eye' of the face has been outlined in black.

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

Another version of the face or mask shown above.

Photo: Leroi-Gourhan (1973)

Two more faces or masks at Altamira, adapted from naturally occurring projections on the wall.

Photo: Leroi-Gourhan (1973)

Perforated bone plates with parallel marks on the rim. Four plates made by cutting and polishing a horse's hyoid bone (the bone that supports the larynx). They are perforated to be used as pendants or to sew onto clothes. They were discovered together forming a group or series; each one had thirty marks at either side. They may represent a recurrent event or something that has been observed, or the verification of something important such as the moon or menstrual cycle, like a notebook. In any case, they would be more symbolic and purposeful than decorative and casual.

(Note that they may well have been bullroarers, and the holes would have allowed the attachment of a long cord, which was than used to whirl a plate around the head, making a roaring noise - Don )

Date: 20 000 - 16 000 BP.

Photo: © Pedro Saura, Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

Bison.

Although these photos are of the same depiction of a bison, they may be of the facsimile of Altamira near Santillana del Mar.

Photo: (left) http://eso-socialscience.blogspot.com/2010/10/palaeolithic-art.html

Photo: (right) Photo: http://www.csj.org.uk/caminodelnorte.htm

Head and forequarters of the bison above.

Photo: Guinea (1979)

Signs at Altamira.

Photo: www.profesorenlinea.cl/artes/ArtePrehistoria.htm

Bison and signs at Altamira.

Photo: Yvon Fruneau

Permission: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license.

Proximate source: Wikipedia

This photograph shows in detail some of the strange abstract lines named 'scutiform' for supposedly representing shields, though this view is but an interpretation which can in no way be proven. They are of the same bright ochre colour as the most outstanding bisons of the cave, so they may be contemporary. Palaeolithic man was surrounded by a symbolic world of which we have no idea, and which was transmitted in abstract figures as well as realistic ones.

Photo and text: Guinea (1979)

( Note that Burgy (2010) interprets the upper part of the sign, consisting of a line surmounted by a triangle, as representing the rising sun. I find this to be unlikely and in any case unprovable.

In addition, the signs, while apparently connected to each other in some meaningful way, are nothing like what are generally called 'scutiform' or shield like. The upper sign, of a line and a triangle, is closest to what is generally called a 'claviform', though most examples are more asymmetric in the placement of the protrusion, and are more rounded than triangular, as we can see on some of the walls of Niaux. However, there are many examples where this triangular form is common, as at La Pasiega cave in Spain.

The term scutiform, for 'shield like', is, to my eyes, somewhat superfluous, since shield like signs are usually grouped with the tectiform signs. See Breuil's sketches and identifications from La Pasiega below.

- Don )

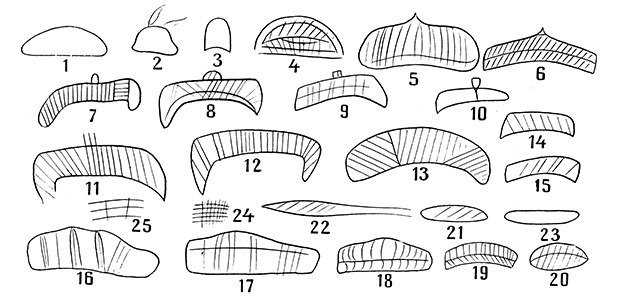

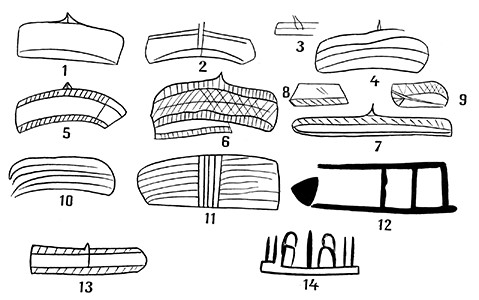

Sketches of the main types of Tectiformes of La Pasiega, grouped for their systematic study.

Older series: 1 to 3.

Primitive and shield shaped types: 4 to 25, second series.

Photo and text: Breuil et al. (1913)

Sketches of the more advanced Tectiforms of La Pasiega for their systematic study.

( note that the ladder shaped number 12, in red, from Salle XI, was at one time believed to have been painted by Neanderthals, though that result has been shown to be unwarranted - Don )

Photo and text: Breuil et al. (1913)

A group of large red claviform signs on the ceiling of a small chamber at La Pasiega. Note that these are almost symmetrical, and somewhat pointed, which is not the case at other caves such as Niaux.

( note the striking resemblance to the venus figure engravings of Lalinde and Gönnersdorf - Don )

Photo and text: Breuil et al. (1913)

Tectiformes at Altamira.

Photo: Jennifer Tanabe

A close up view of part of the tectiformes above,

found in the terminal gallery known as the "Cola de caballo" (Horse tail).

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

These tectiformes are in a gallery only one metre high by one metre wide, in the deepest part of the cave, the "Cola de caballo" (Horse tail). Cultural motivations brought people there at different times to draw and engrave these signs, 250 metres from the entrance. They entered the cave with wooden torches or fat lamps to be able to draw this group of reticulated (net shaped) signs, strictly compartmentalised and repeated next to the most prominent crack in this deep gallery.

Photo: Altamira National Museum and Research Centre © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

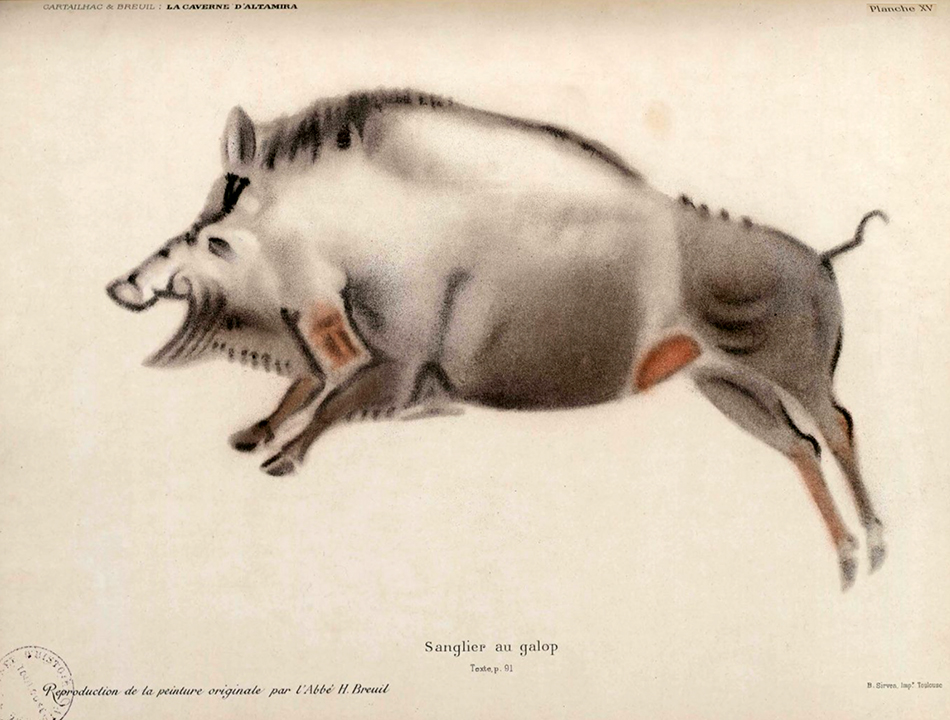

Wild boar near the entrance.

Length: 1.65 meters from the base of the tail to the snout.

The animal is quite fuzzy 'and damaged ' - according to Breuil - 'by the decomposition of the rock surface due to the condensation of water vapour from the outside air that enters the cave'. Breuil also says that by being near the entrance it has deteriorated, 'especially since 1902 '.

The animal is in the act of jumping, with forelegs elevated and forward. There is hardly any shading with ochre, with just black smudging to indicate the body of the animal. The hind legs and the lower abdomen have been engraved, and much of the interior of the figure has been scraped back.

(Note that Bahn (1999) states quite categorically that this is a bison. - Don )

Photo: http://www.cuevamuseoaltamira.com/

Text: Translated and adapted from Guinea (2011)

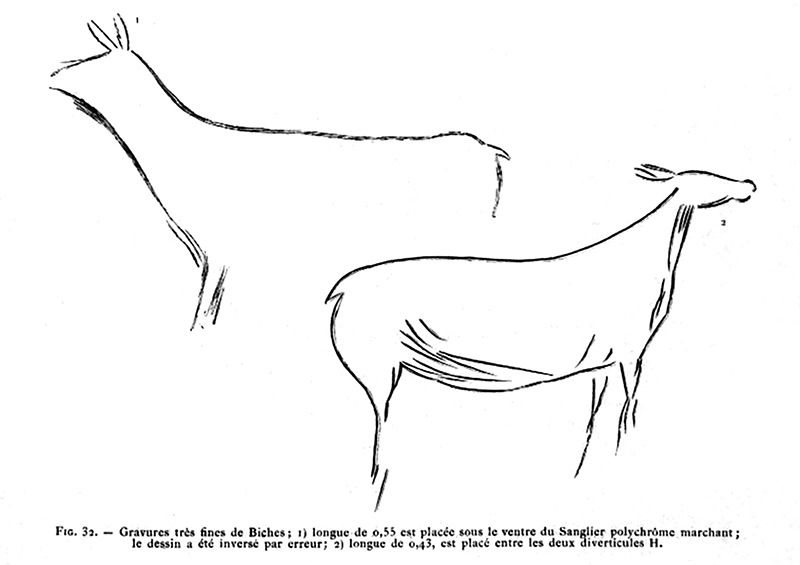

Figure 32

Very fine engravings of Hinds.

No. 1, left, is 55 cm long and is placed under the belly of the walking polychrome Boar; the drawing was reversed by mistake.

No. 2, right, is 43 cm long, and is located between the two diverticula.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

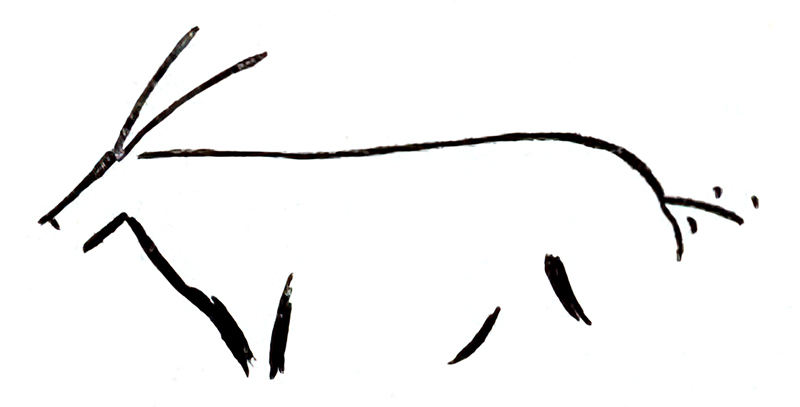

Figure 3

Tracing of a drawing of an ibex. Length 35 cm.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

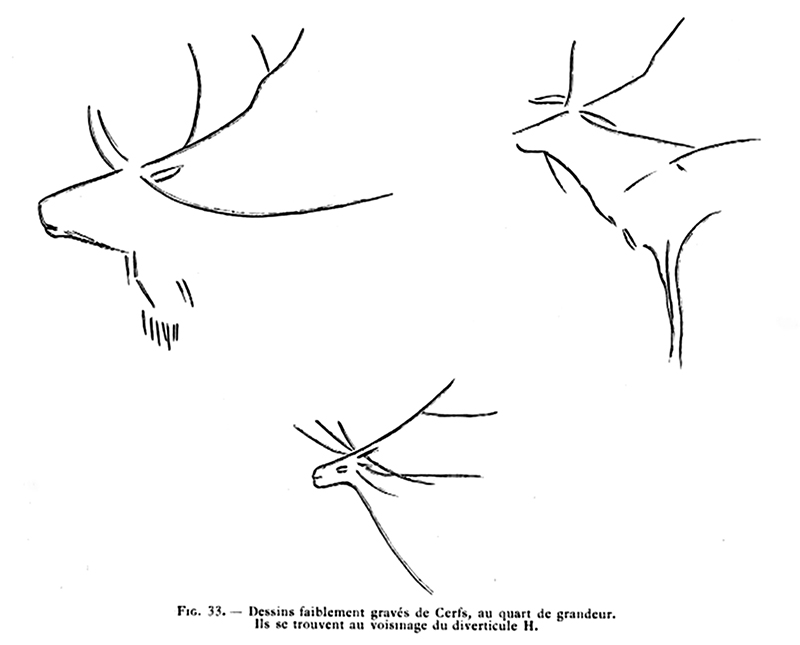

Figure 33

Faint drawings of deer, in the vicinity of the diverticulum H.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

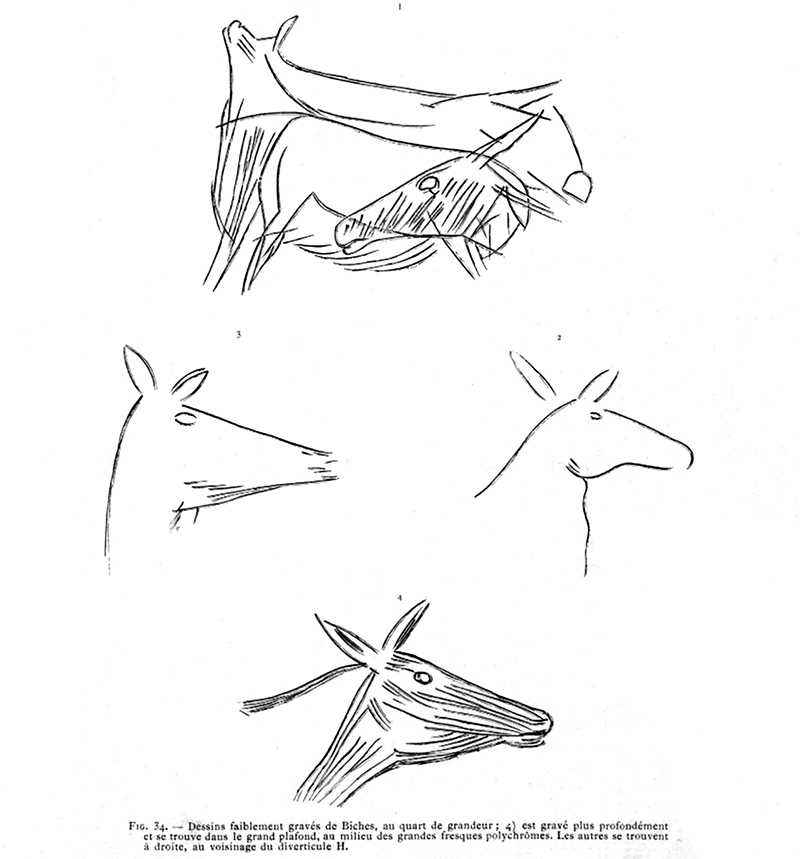

Figure 34

Faint drawings of deer.

4) is more deeply engraved and is located in the large ceiling, in the middle of the large polychrome frescoes. The others are on the right, in the vicinity of diverticulum H.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

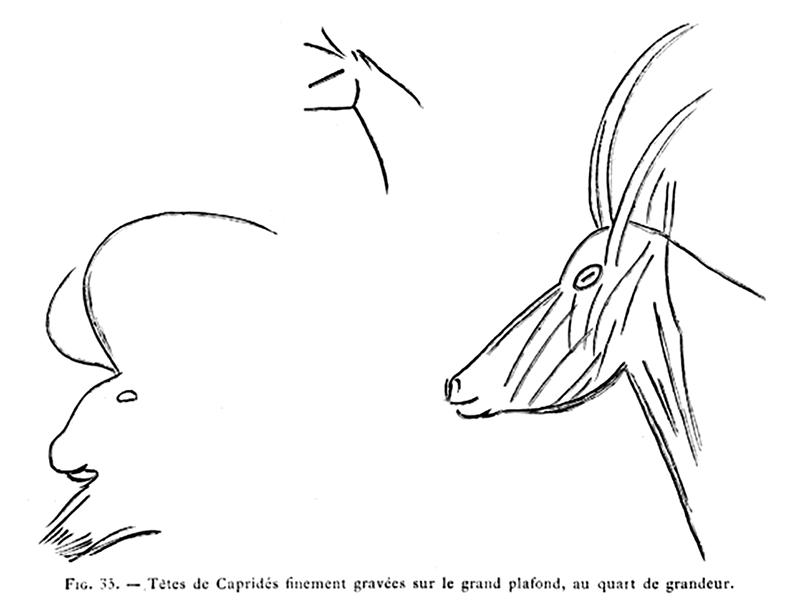

Figure 35

Heads of caprids finely engraved on le grand plafond.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

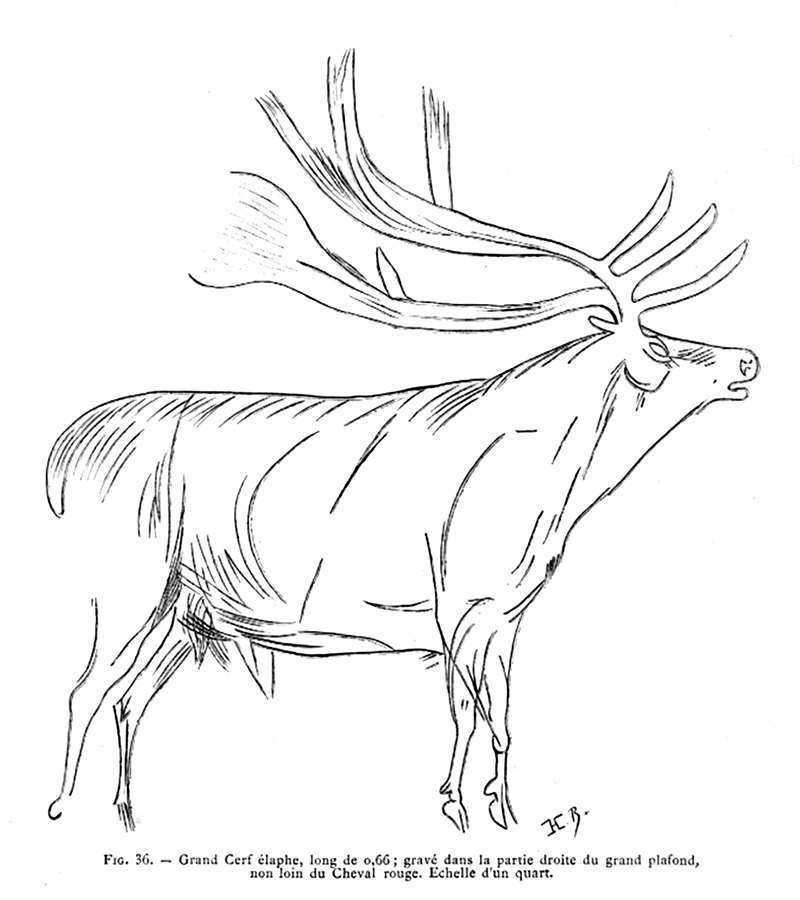

Figure 36

Large Red Deer, 66 cm long; engraved in the right hand side of le grand plafond, not far from the red horse.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

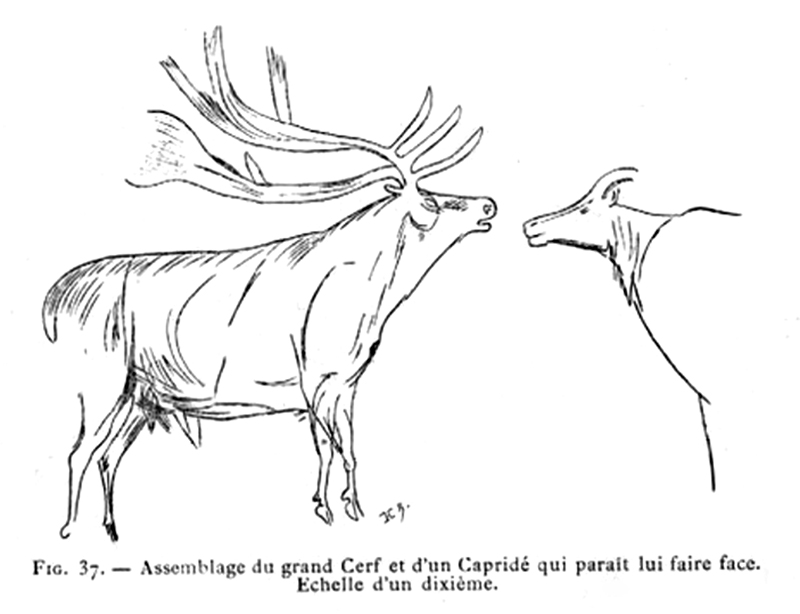

Figure 37

The assemblage of the great stag of le grand plafond shown above, and a Caprid facing him.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

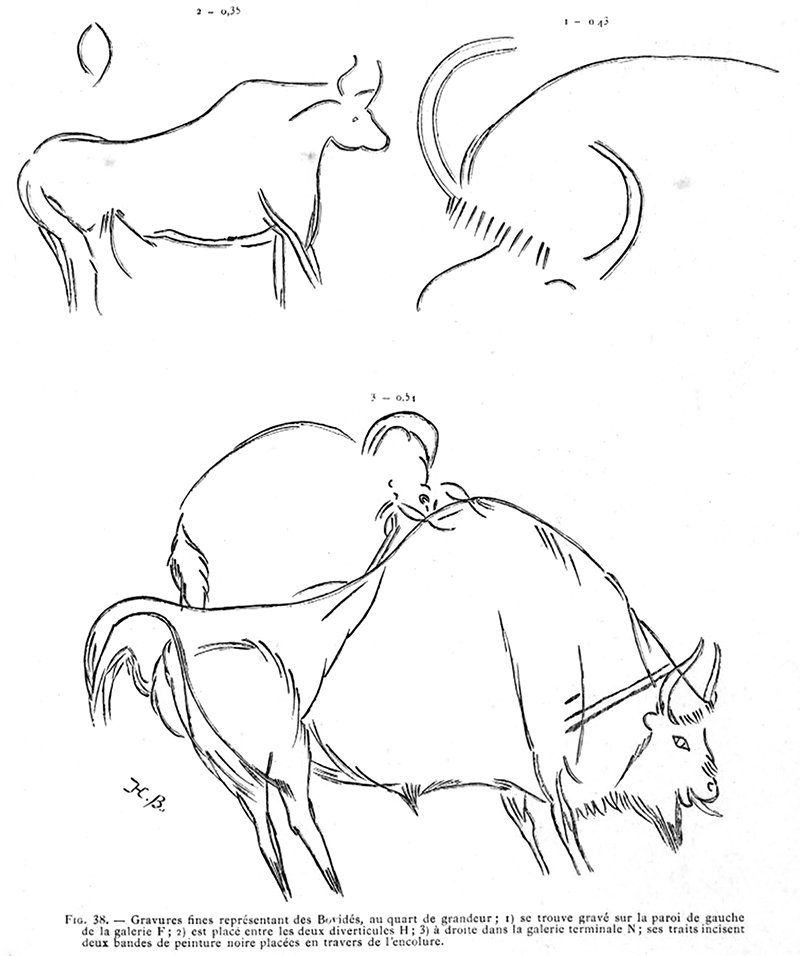

Figure 38

Fine engravings representing Bovids.

1) is engraved on the left wall of gallery F, 43 cm.

2) is placed between the two diverticula H, 35 cm.

3) on the right in the terminal gallery N; its lines incise two bands of black paint placed across the neck, 51 cm.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

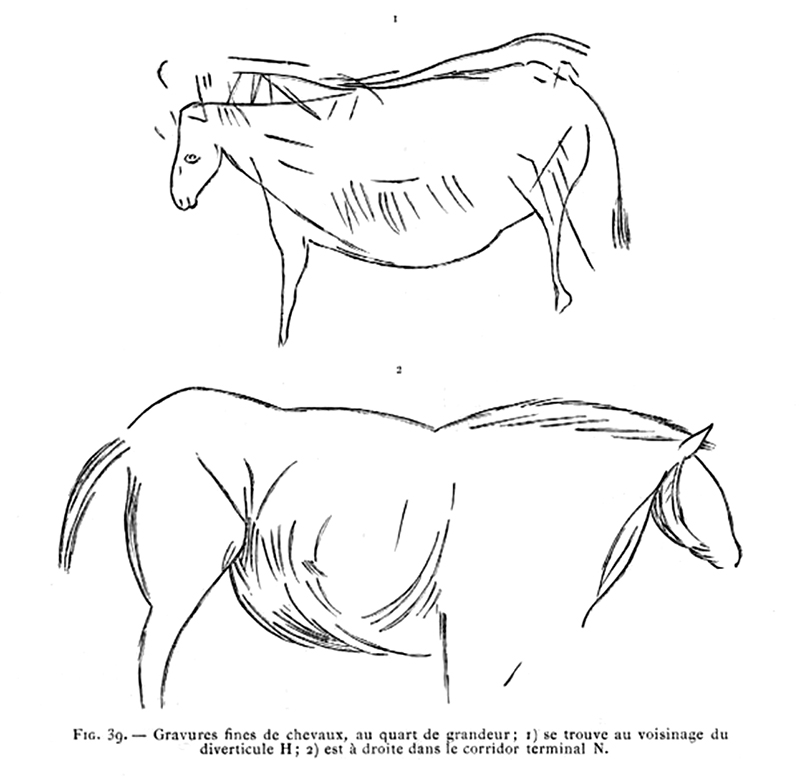

Figure 39

Fine engravings of horses.

1) is in the vicinity of the H diverticulum.

2) is on the right in the terminal gallery N.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

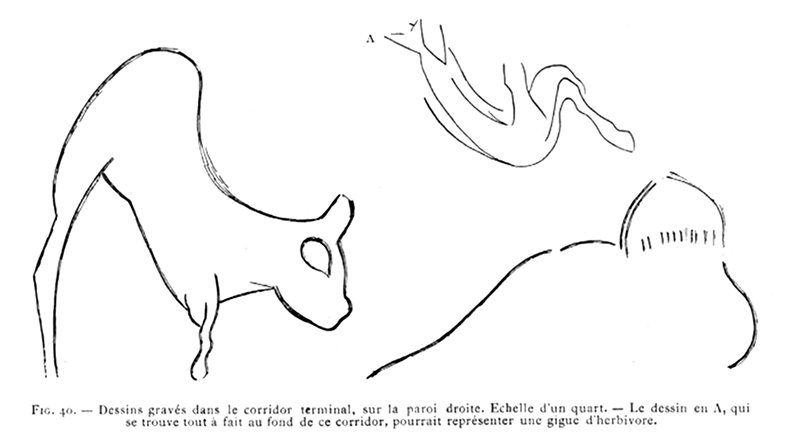

Figure 40

Engravings in the terminal corridor, on the right wall. The drawing A, which is located at the very end of this corridor, could represent a prancing herbivore.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Figure 50

Black paintings from the Altamira Cave representing Horses.

1 to 5 located in the deep part of the large ceiling

6 located between G and H of the plan (2nd gallery).

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

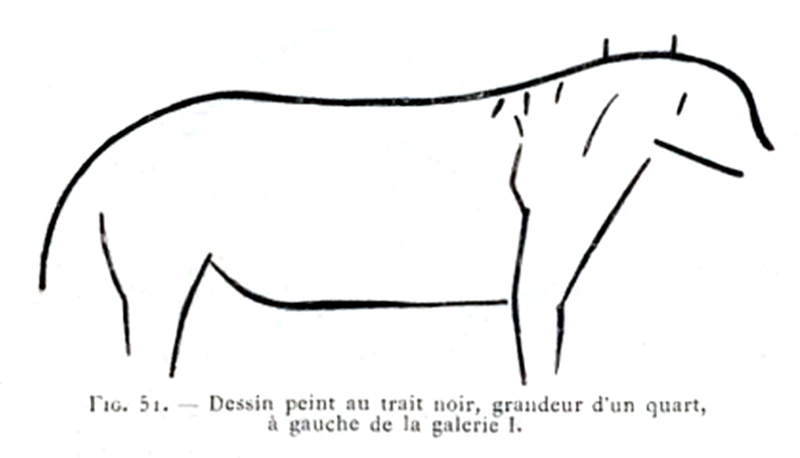

Figure 51

Drawing in black, to the left of Gallery I.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

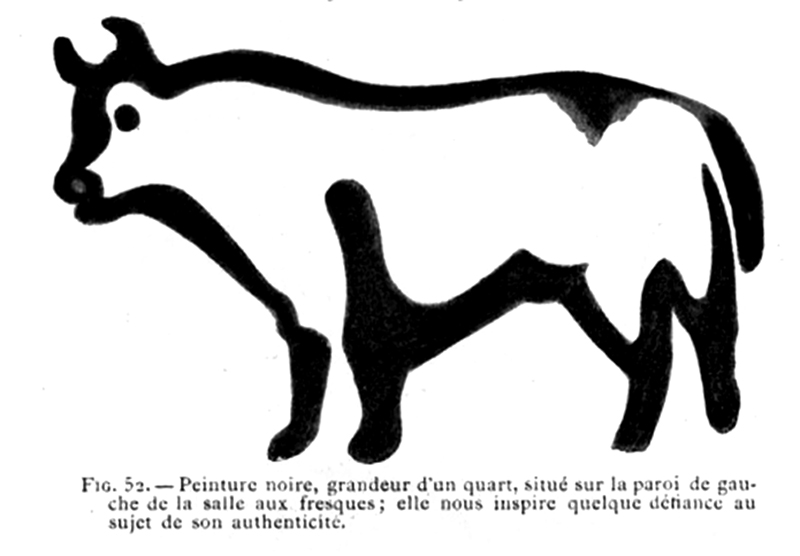

Figure 52

Black painting, located on the left wall of the frescoed room; it inspires some doubts about its authenticity.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

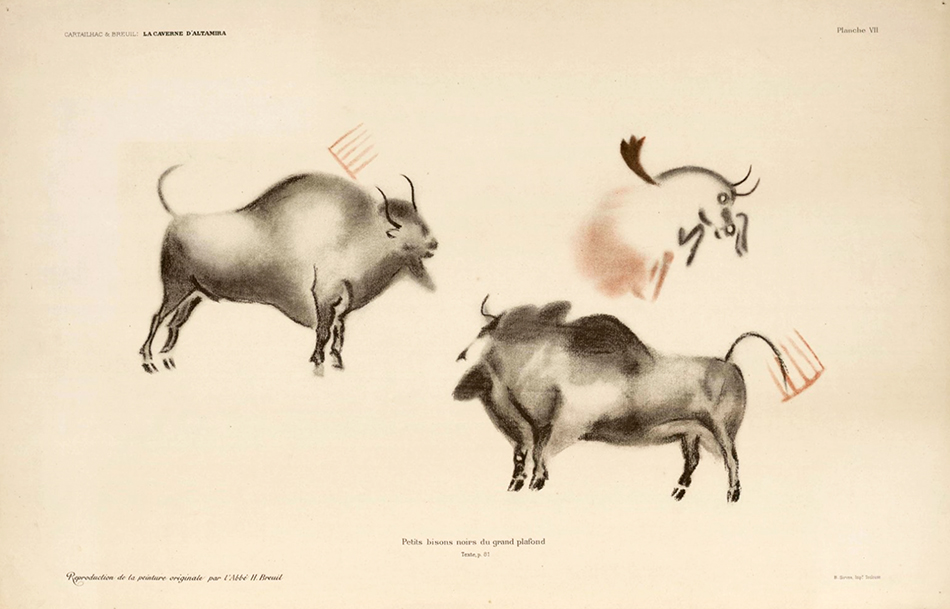

Plate VII

Small bison painted in black, modelled on le grand plafond, and a red pectiform sign (a stylised hand).

Dimensions of the bison, from the base of the tail to the nostrils: 90 cm.

Shown is a bison bellowing. Very faint engraving marks on the nape of the neck, stronger on the dewlap.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

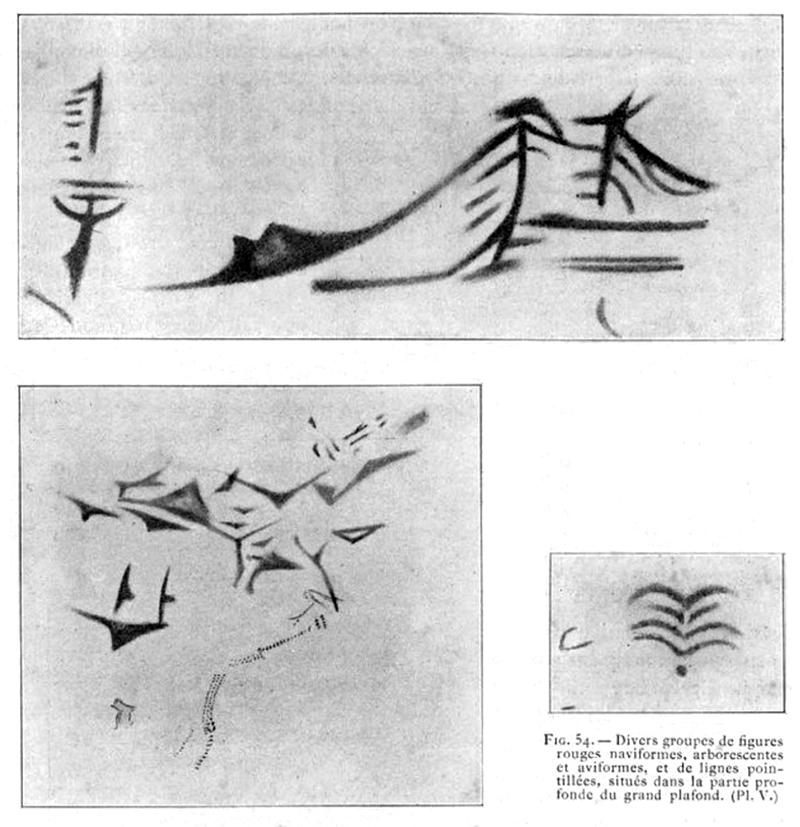

Figure 54

Various groups of red boatshaped, tree-like and bird-like figures, and dotted lines, located in the far end of la grande plafond.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

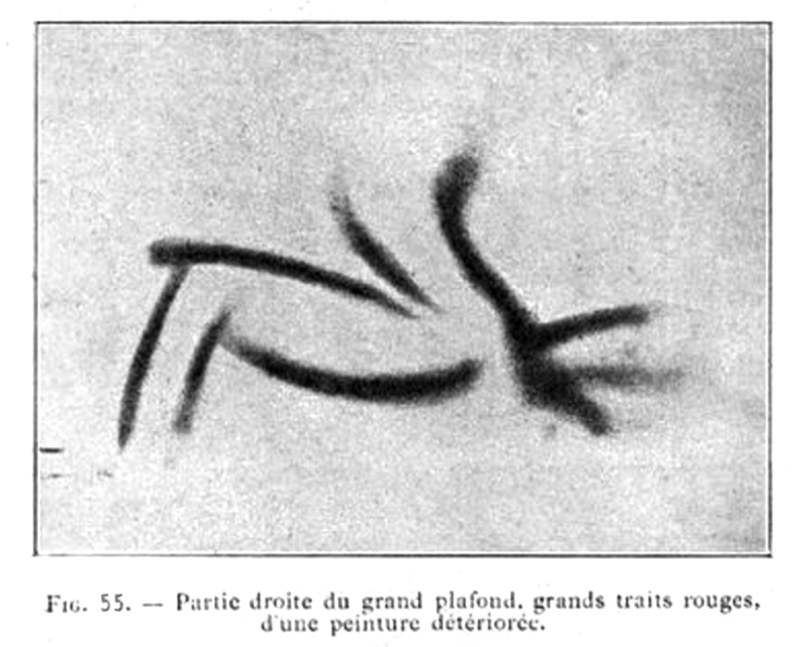

Figure 55

Right side of la grande plafonde, large red lines of a deteriorated painting.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

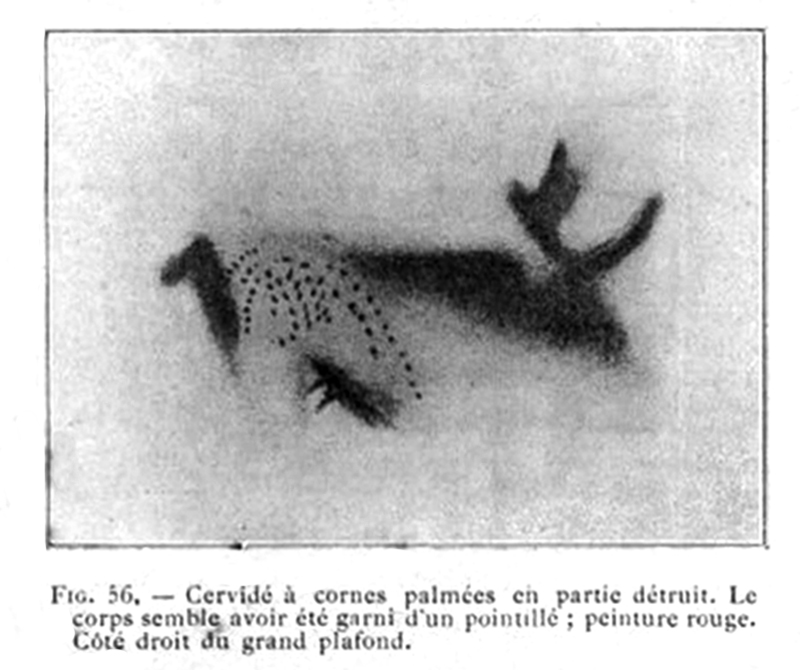

Figure 56

Cervid with palmate antlers, partly damaged. The body seems to have been trimmed with stippling, in red paint.

Right side of la grande plafond.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

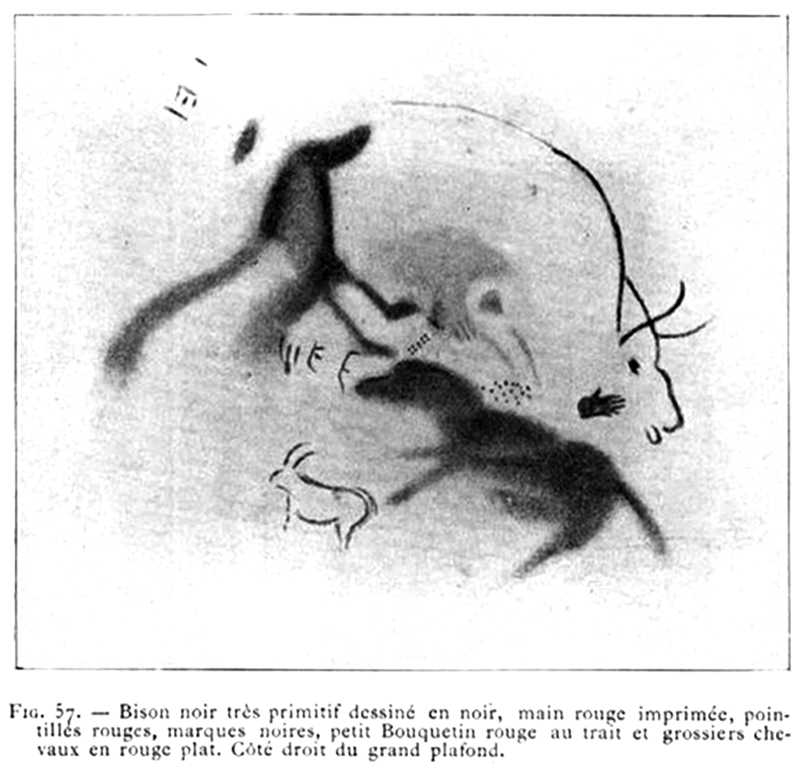

Figure 57

Very crude black bison drawn in black, a red 'positive' hand, red dots, black marks, a small red ibex in outline and rough paintings of horses in red.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

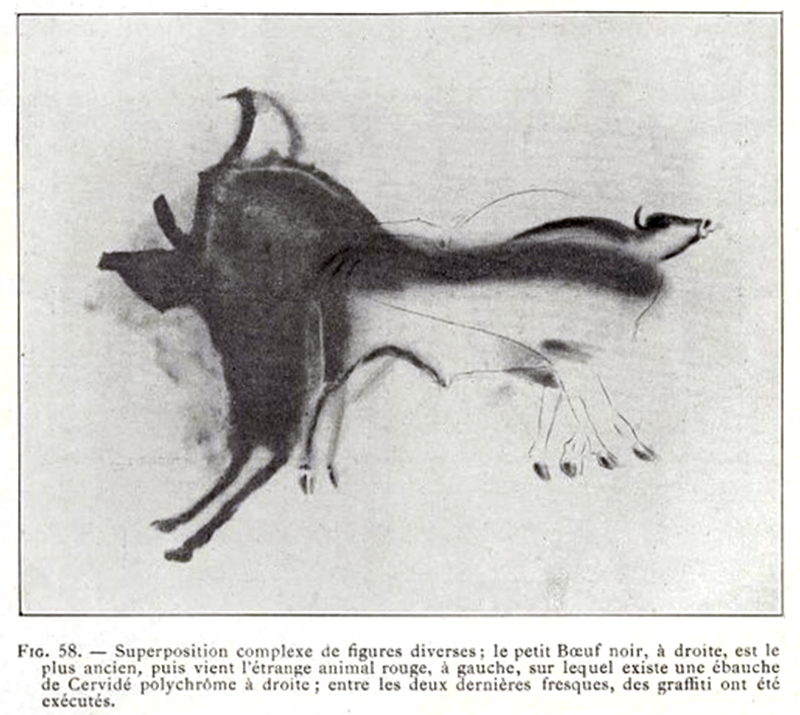

Figure 58

A complex superposition of various figures; the small black aurochs, on the right, is the oldest, then comes the strange red animal, on the left, on which there is a polychrome cervid sketch on the right; between the last two frescoes, graffiti has been executed.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

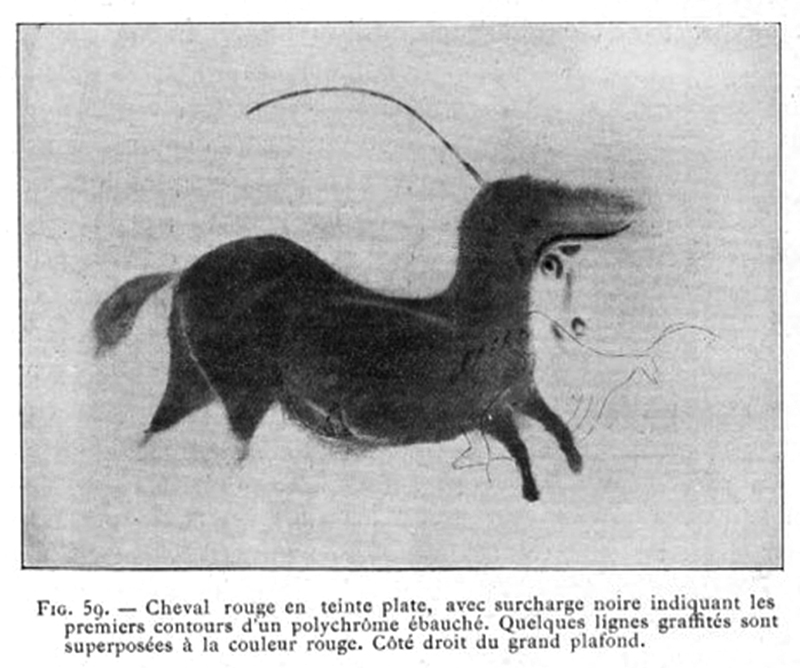

Figure 59

Red horse in a flat tint, with a black overprint indicating the first contours of a polychrome sketch. Some graffiti lines are superimposed on the red colour. Right side of la grande plafond.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

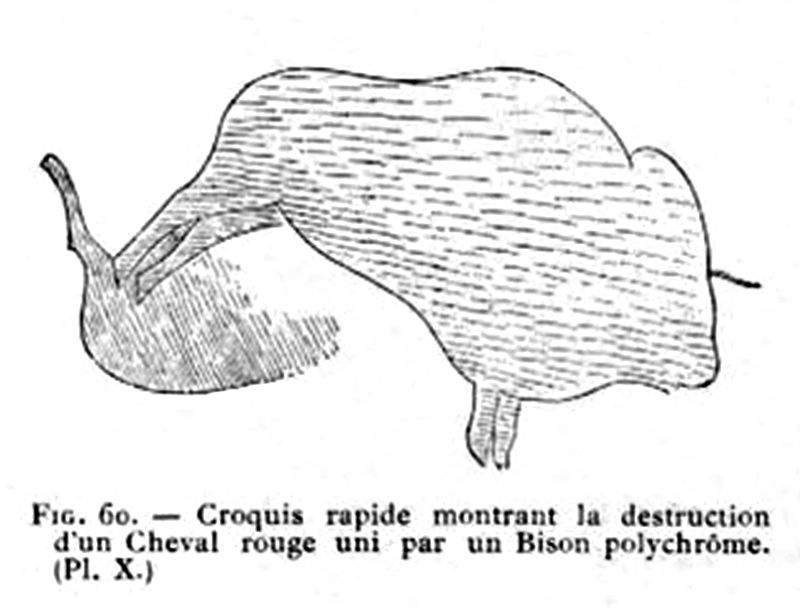

Figure 60

Quick sketch showing the 'destruction' (?) of a plain red horse by a polychrome Bison.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

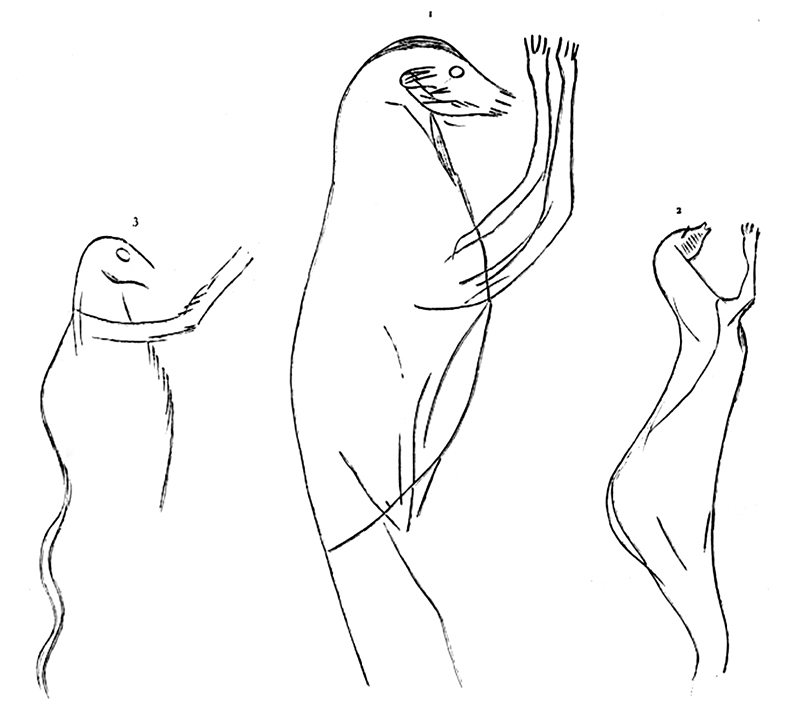

Anthropomorphic Drawings

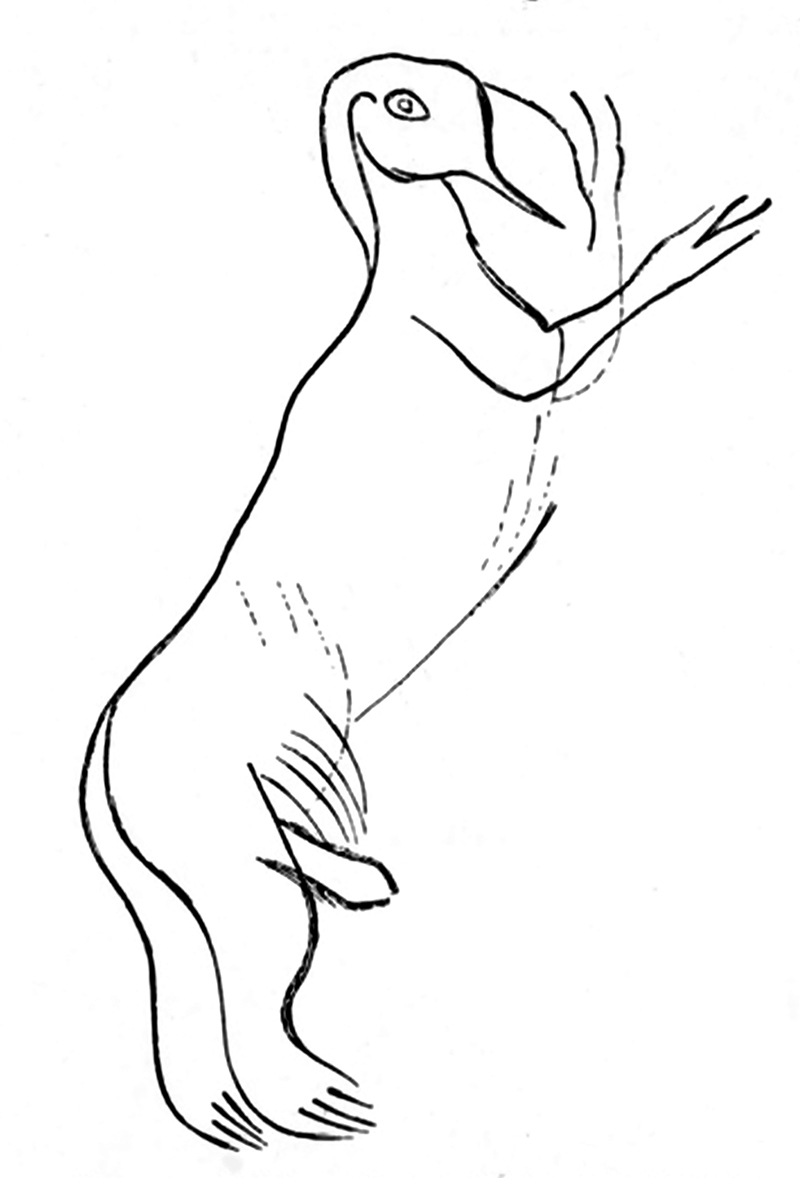

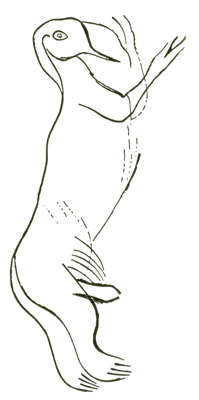

Figure 41

Graffiti appearing to represent human beings, probably wearing masks, and raising their arms in the air.

1) is 60 cm high, and is located between the Walking Boar and the left wall of the large frescoed room.

2) 40 cm high, in the bellowing brown buffalo.

3) 40 cm above the loins of the great Doe.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Figure 42

Graffiti appearing to depict human beings, probably wearing masks, and raising their arms in the air.

1) 35 cm, near the Walking Boar.

2) 22 cm, at the armpit of the Great Doe.

3) 30 cm, in the shoulder of the Walking Boar.

4) 32 cm, on the right side of le grand plafond, in the areas with boat shaped figures.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Figure 43

Anthropomorphic figure similar to the previous ones, located near the front feet of the large Hind. The dashed lines are uncertain; the phallus is in champlevé.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

The Bird Men of Altamira

Bird-man of Altamira, L'homme-oiseau, un des sorciers de la grotte. This drawing was made originally by H. Breuil.

Photo: http://lithos-perigord.org/spip.php?rubrique25

Photo: Meller et al. (2010)

(originally from Abramova (1995))

I have been unable to find more than fleeting references, and a few drawings, of the hommes-oiseau of Altamira. The Lascaux version is well documented.

Here is one of the few text references, from Groenen (2011):

L’homme-oiseau a été repéré dans la scène du Puits de la grotte de Lascaux, sur le Grand Plafond de la grotte cantabrique d’Altamira et dans la grotte d’Addaura en Sicile. À Lascaux et à Altamira, le motif articule une tête d’oiseau, bien reconnaissable à son bec, à un corps, aux bras et aux jambes d’un être humain. En outre, le sexe, masculin, est en érection.

The bird-man has been spotted in the scene of the Well of the Lascaux cave, on the Great ceiling of the cave of Altamira and at the Cantabrian cave of Addaura in Sicily. At Lascaux and Altamira, the pattern shows a bird's head, easily recognisable by its beak, a body, arms and legs of a human being. In addition, the penis on the masculine figure is erect.

Another version of one of the figures from Altamira.

Photo: Bataille (1989)

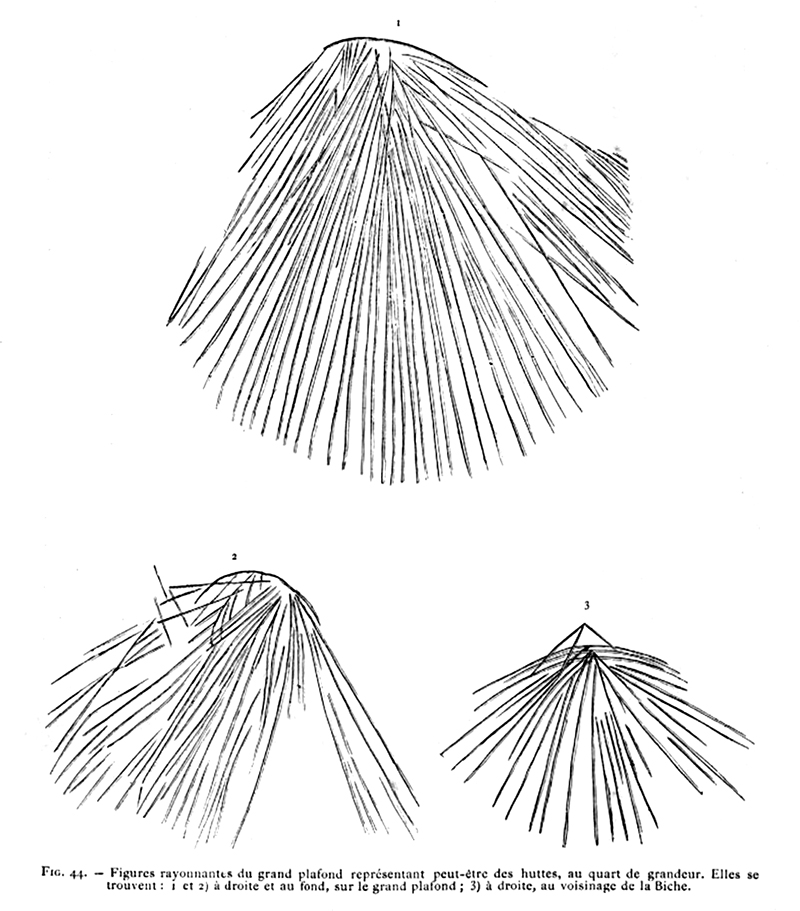

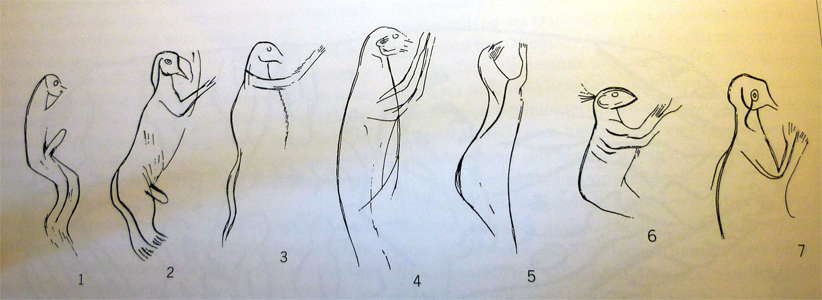

Figure 44

Radiant figures on the large ceiling possibly representing huts.

They are:

1) and 2) on the right and at the back, on le grand plafond.

3) on the right near the Hind.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

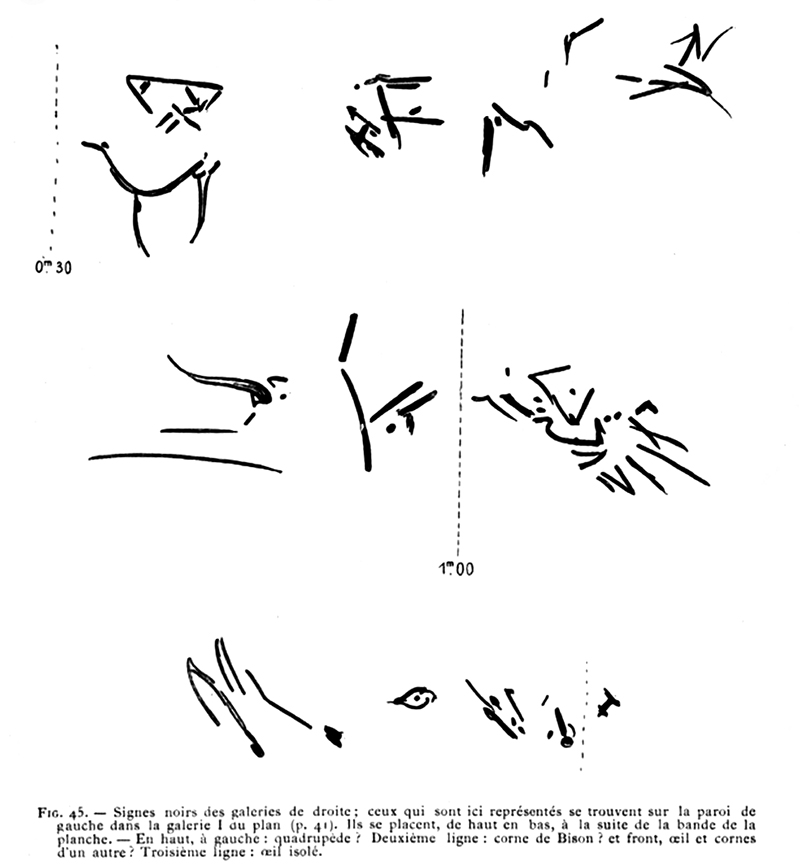

Figure 45

Black signs from the right-hand galleries; those shown here are on the left-hand wall in gallery I of the plan.

They are placed, from top to bottom, following the band of the plate.

Top left: quadruped? Second line: horn of a Bison? and forehead, eye and horns of another? Third line: isolated eye.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

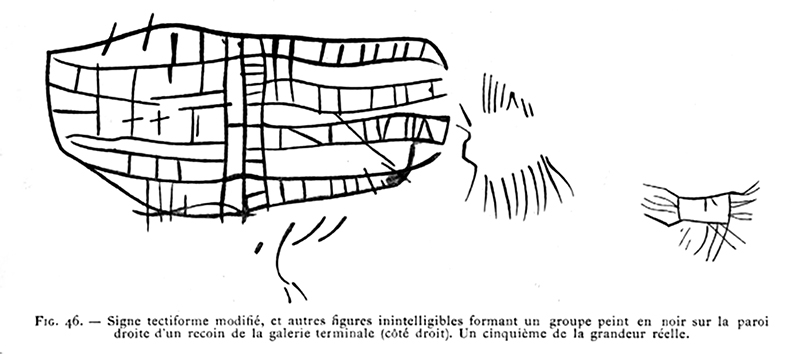

Figure 46

Modified tectiform sign and other unintelligible figures forming a group painted in black on the right wall of a corner of the terminal gallery (right side).

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

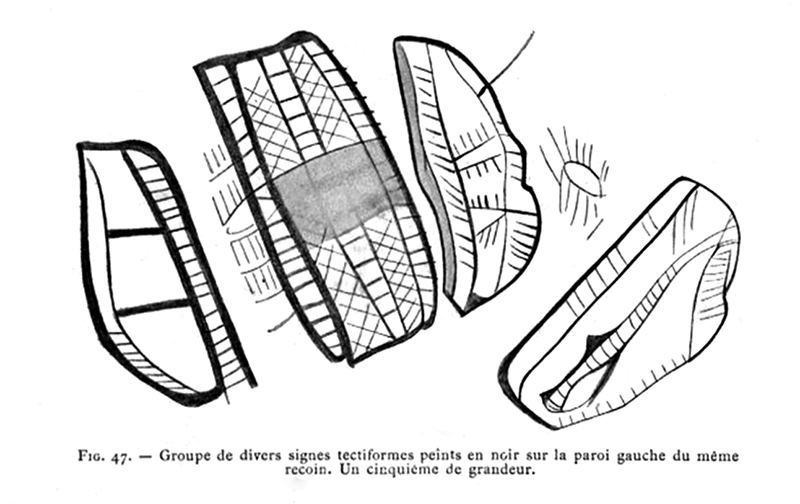

Figure 47

Group of various tectiform signs painted in black on the left wall of the same recess as figure 46 above.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

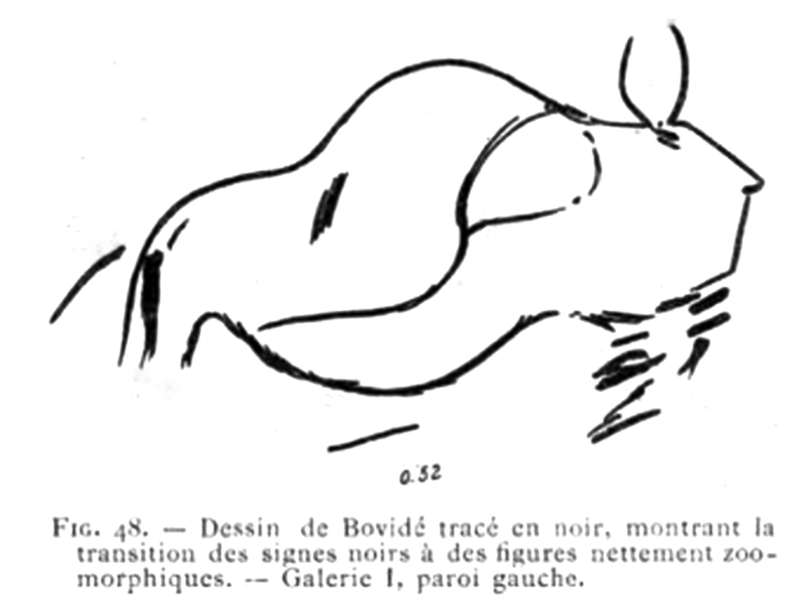

Figure 48

Drawing of Bovids drawn in black, showing the transition from black signs to clearly zoomorphic figures - Gallery I, left wall.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

A horse in red, an ibex and a hand. These match the art from the Gravettian era, the earliest era with human presence in the cave. (to me this horse is similar to the art of Lascaux, which is from a later period - Don ) The horse's silhouette is filled in with red. Next to it there is the shape of a hand on the rock and an ibex drawn with simple lines.

The ceiling was filled initially with red figures, especially horses. Then, many does and a few deer were engraved next to some figures that are shaped more like humans. Later on, polychrome bison (also a doe and a horse) covered the ceiling almost entirely. And finally, some bison, completed only in black, took up the remaining free space just before the cave stayed completely dark when the entrance collapsed.

Photo and text: © Pedro Saura, Altamira National Museum and Research Centre, © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

This shows the image above in context, with other horses around it, apparently contorted out of shape.

Note the two negative imprints of hands in black, superimposed over other images.

Photo: © Pedro Saura, Altamira National Museum and Research Centre, © Ministry of Culture, http://www.spainisculture.com/

Bison.

Photo: Guinea (2011)

Head and neck of a polychrome hind. Below, on the right, small bison in outline. From the picture gallery, Altamira.

Length of hind: 7 ft 4.5 inches, 2250 mm.

Photo: Original, Leroi-Gourhan (1992)

The complete hind at Altamira.

Photo: http://eso-socialscience.blogspot.com/2010/10/palaeolithic-art.html

Another version of the hind at Altamira.

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

Aurochs engraved with the fingers on the soft clay of gallery III. Tracing H. Breuil, 1935.

Photo: Lasheras (ca 2008)

Horse.

( This appears to be an unfinished composition - Don )

Photo: Guinea (2011)

Horses on the ceiling, incompletely outlined in black.

Photo: http://www.quesabesde.com/noticias/nomada-altamira-museo,1_5259

Horse and hind from Altamira, at the top left of the image above.

Photo: After a drawing by Abbé Breuil

Source: Lubbock (1913)

Permission: Public Domain

Ceiling at Altamira. Length about 45.5 feet

Photo: 1911 Encyclopaedia Brittanica

Permission: Public Domain

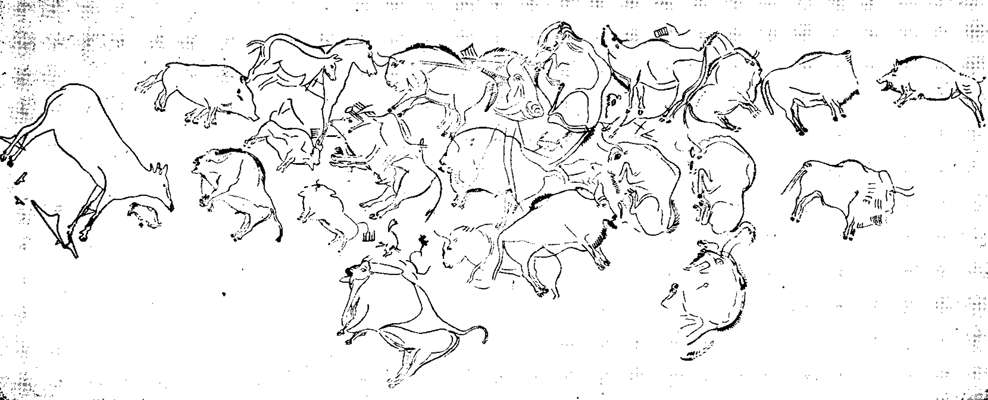

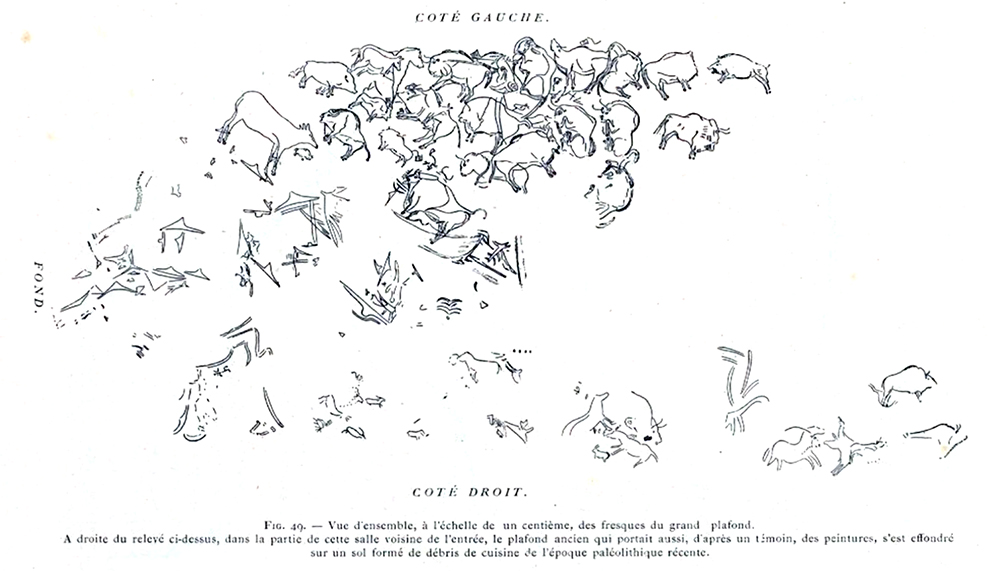

Figure 49

General view of the frescoes on the large ceiling. To the right of the above survey, in the part of this room next to the entrance, the ancient ceiling, which was also painted, according to a witness, has collapsed on a floor made of kitchen debris from the recent Palaeolithic period.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

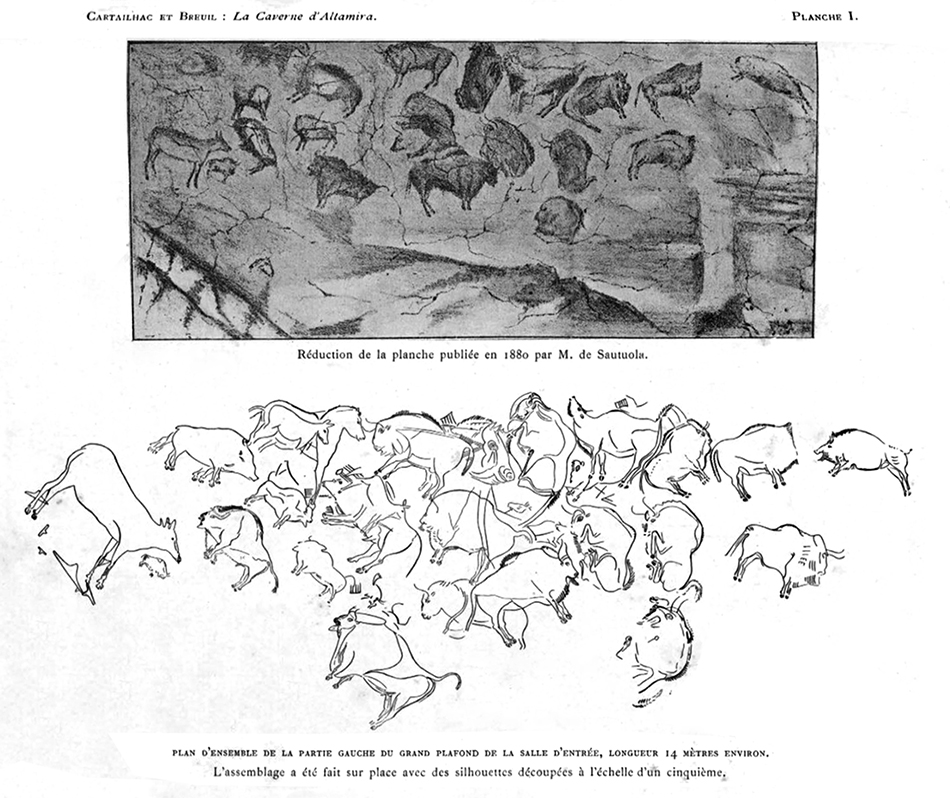

Plate I

Overall plan of the left side of the large ceiling of the entrance hall, about 14 metres long. The assembly was done on the spot with cut out silhouettes.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

The Frescoes in the Galleries

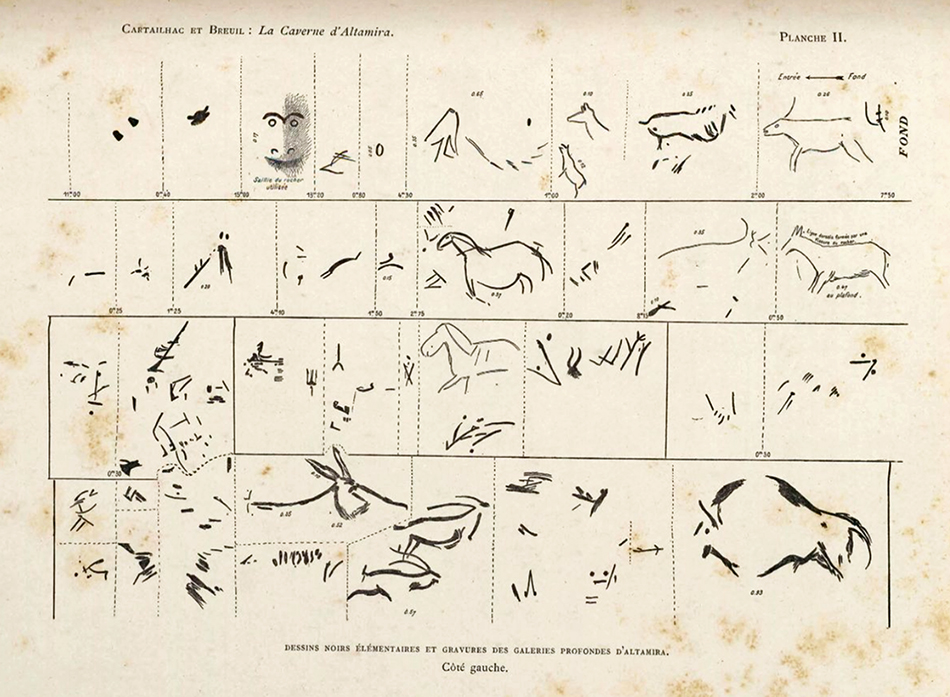

Black signs and red signs (Plates II, III, IV)

The black signs appear in the same conditions as the engravings. They appear at the same levels, often on the same surfaces without there being any intentional neighbourhood or relationship between them.

Two very fortunate cases of superposition have made it possible to certify the antiquity of the black signs. One of them, in fact, is clearly intersected by the features of the small bison, which we have pointed out in the corridor at the back. Another is also crossed by the engraving of a doe.

These black signs are quite particular to the Altamira Cave. It would be impossible to classify them chronologically without the good fortune of this double superimposition, which dates them and confines them to a very remote past.

The first ones are in the main gallery around the diverticulum. They will continue to the ends of the cave. Some are simple dots, a few circles, angles, short and uneven lines, sometimes crossed, singular arrangements, rarely complicated.

They look like cursive characters of an unknown alphabet (Plates II and III.) But out of about one hundred and twenty that we have found, not two are similar. Moreover they are scattered without appreciable order at a greater or lesser distance from each other.

They are therefore not letters. Could they be marks of passage drawn to reassure the visitor to the cave and allow him to find his way back? They would then have been placed on clearly visible surfaces. However, there are some very hidden ones. Moreover, these signs are not elementary enough to have had the sole aim of marking a route already followed.

Are they landmarks? They have forms that would be of no use to us for this usage. They are not clear, not distinct enough, and too numerous to indicate a specific place. They are missing at certain junctions where landmarks would ordinarily have been necessary.

Their indisputable antiquity, since they preceded the Palaeolithic graffiti, confirms their importance. They had a meaning comparable perhaps to those conventional inscriptions on the 'message sticks' of the Australians or the Javanese Negritos, of which we shall speak again. We do not know whether they provided indications to the initiates during mysterious ceremonies.

Some of them vary within a uniform framework. Linear strokes, reminiscent of Japanese writing, are followed by sketches of animals, sometimes quite complete profiles in which we find qualities that attest, at least once, to the skill of a hand as practised as the one that drew the engravings, or portions of images, a head, a muzzle, a few lines of the back, a neck, hindquarters.

One sign has some connection with a Sperm whale, at least with a fish which would be surmounted by a squirrel (Plate III, 4th line of the painting, 4th fig.) In this respect we are struck by the fact that there is only one figure which reminds us, yet still with some doubt, of the world of the sea.

Fish engraved on bone appear quite often in our stations, in the Périgord or in the Pyrenees, and elsewhere. Several species have been represented with great care and talent.

Nothing like this has ever appeared on the walls of our decorated caves. At Altamira the troglodytes were close to the ocean, whose shell products flowed into the cave, and one might have expected to see marine fauna playing a role among so many engravings and paintings, but this is not the case. Towards the back, the corner of a protruding stone bears a singular mask (Plate I, first line of the painting, 3rd fig.): two strongly traced superciliary arches, two small circles in place of the eyes, two nostrils, the mouth vaguely represented by a natural depression. This detail is interesting.

The use of the accidents of the rocky surfaces to perfect the images we have already observed in Marsoulas. Altamira has still better examples of this original process in its paintings.

Opposite this strange muzzle, a little further on, one stops with astonishment in front of a group of signs, of which we have already said a word, very visible and original. The right wall of the gallery has an obtuse angular depression whose sides are about 80 cm in length; on each side figures are spread out with a certain symmetry, five against three.

To the main signs, others are added, similar to small radiating suns, perhaps stylised images. The main series, at first, made us think of shields decorated with squared bands, of varied designs; each of them has its own design. The shields of the Cafres, Australians and other primitives sometimes have the same appearance in general form and in decorative detail.

However, we will support another hypothesis: despite significant differences, they are tectiform signs like those of Font-de-Gaume, La Mouthe, Combarelles, Bernifal and Marsoulas. It remains to explain the situation of these very particular figures which, without doubt, are not banal and without significance.

No explanation satisfies us, and this is not the first nor the last time that we have questioned prehistoric inscriptions in vain. Ethnography does not stop our embarrassment. We do not perceive any document revealing the customs of the past. The mystery of the black signs, considered either individually, in series or as a whole, remains impenetrable.

One conclusion at least emerges and can be envisaged. There are some links between the large series of graffiti, animals engraved with a line, and some of the black signs, animals drawn with a brush.

The engravings and zoomorphic paintings are reminiscent of the studies that artists like to draw in a scrapbook in order to improve and entertain themselves, a sheet of paper, a board or a slate, on any surface likely to retain the trace of the pencil, the pen or a hard point. But alongside the sketches of animals come the black signs whose abundance, variety and strangeness we have mentioned.

They claim for themselves, it seems, and consequently for all the rest, a general, different and better explanation. Before continuing our investigations, let us stop on a technical detail. We have just written the word brush. It is true that a well-made brush was used, and there were small brushes and large ones in the hands of the artists.

There are no smudges or irregularities that would reveal other processes here and there. We are not in the presence of the works of the first comer, using what he could have had at hand. There is no accidental fantasy, but a clear goal that has been achieved with the experience acquired from certain appropriate procedures.

Let's enter the diverticulum, the place where we have already stopped several times. It has some surprises in store for us. Two metres wide at its opening, this vertical fissure rapidly narrows and closes at a depth of 4 or 5 metres.

Its ceiling is flat, formed by the stone foundation that extends to this level, about 3 metres above the ground, and it is easy to pull yourself up by means of the asperities of the walls, if you want to reach it and touch it.

As soon as you reach the threshold, you can see four signs painted in brown lines on this vault, ovals crossed twice each, very symmetrical, juxtaposed. Further down, on the left, the wall has quite different signs, very red on the whitish surface.

It is a ribbon in the shape of an S-shaped ladder; next to it another scaliform figure is attached to the end of a straight line: it looks like the image of a spear with its flame, of a flag unfurled at the end of its horizontally extended staff. Below, near the ground, reddish spots are perhaps the remains of other signs (Plate IV, figs. 3 to 6).

On the left side, one does not see anything special at first. But if you bend down, you will see that the underside of a rocky bed, which rises 20 or 30 centimetres, has been ornamented over a length of 2 metres.

The soil in this area appears to have been raised by a significant amount of water, which has been added to the bedrock by the infiltration of water into the ground.

One can therefore admit that in the past, when entering, one saw all this red ornamentation. The general aspect of the place, the situation of the signs, everything contributes to impress the modern visitor who tries to guess something of the life and customs of the people of former times; there, everything indicates to them a consecrated place. (Fig. 26, p. 40.)

In the other parts of the Altamira cave we will not find these red ribbons in the form of a ladder. However, in a privileged area of the large ceiling, a large surface is covered with red signs, all different. The four brown signs on the ceiling, which obviously mark the reduction of a mysterious seal, are less isolated. They are related to the simplest of the black scaliform or tectiform signs, and consequently to the whole group.

It seems essential to us to underline this unquestionable relationship between the red series and the black series. We are thus led to insist again on the value of the motives that led to the drawing of such figures and the facts that could be derived from them. So far we see confirmation of the fact that the signs, whose interest and equal antiquity are obvious, seem to be due to concerns of the same order.

Plate II

Elementary black drawings and engravings from the deep galleries of Altamira. Left side.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

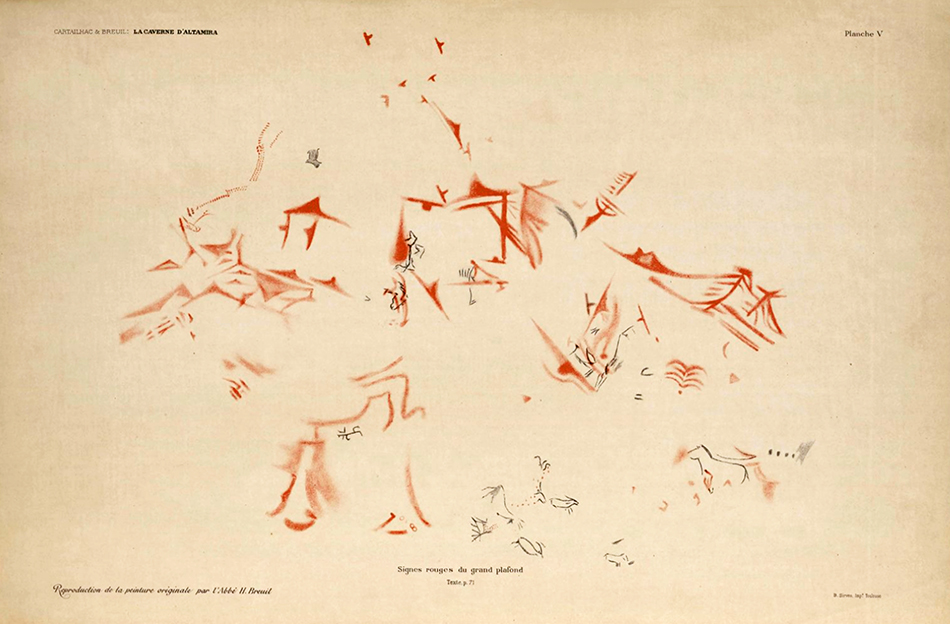

Plate V

It is useless to identify exactly, we are not sure of anything. Once again, we prefer uncertainty to random assertions, and if we call these signs naviforms (boat shapes) it is only to designate them with a word that will help us to quote them on occasion. In the area of the polychrome frescoes we notice that several signs are crossed, erased by these paintings. The legs of the doe, which is one of the best paintings, and one of the neighbouring bisons are in this case.

Elsewhere a large double line snakes through the animals which cover it in large part. It is therefore possible to certify the anteriority of the red signs. The dotted lines and the classified naviforms remain a less homogeneous series, even less susceptible to interpretation.

One of these signs has some vague connection with the sketch of a fir tree (Fig. 50). Similar images in some Chinese or Japanese hastily made ornaments would indicate a landscape, a hill in the background, some trees in the foreground. We have to recall here the lines painted at Marsoulas, without insisting on this comparison except to recognise that in any case it is a question, in these various pictorial manifestations, of the same degree of intelligence and the same level of material civilisation.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

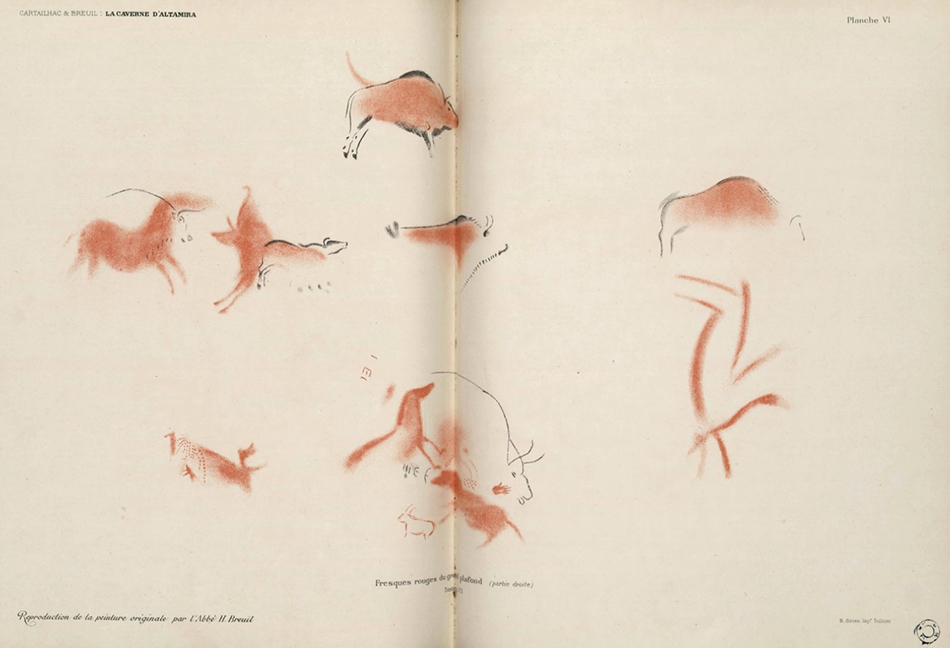

Plate VI

Red frescoes of la grand plafond, right part.

(Fig. 55. - Right part of the large ceiling, large red lines, of a painting deteriorating .)

( 56, - Cervid with webbed ornaments partly destroyed. The #body seems to have been trimmed with a poinuillé; red paint. right of the large ceiling.)

Here and there, finally, one suspects that the features that intrigue us are no more than shreds of figures that have been more than half erased. On the right-hand side, in fact, there is a small ibex drawn in red (Fig. VI) and an animal that could be a large Deer (Fig. 55), painted in the same way (1), but with broader strokes, and another with palmed horns whose very destroyed body is dotted (Fig. 56). The latter establishes a new relationship with the Marsoulas cave and its dotted bison.

Along the right-hand wall there are several uniformly painted animals; although they are quite deteriorated and of a very inferior workmanship from the point of view of drawing, one can nevertheless recognise the remains of several Horses (Fig. 57 and Pl. VI) and perhaps of a Cervid (Fig. 58 and Pl. VIH); the way in which the legs of these animals have been drawn is particularly stiff and mala fide (Fig. 59).

In terms of their relative position in relation to the black and polychrome paintings, there is no shortage of superpositions; Plate VIII shows us a black Bovid, destroyed by a uniformly red Cervid, which itself is being cut by the started execution of a polychrome animal (Fig. 58); the red Horse of Plate IX has

-->

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Small black bisons from la grand plafond.

Plate VII

Dimensions of each of the bisons, from the base of the tail to the nostrils: 0.90 m.

On the left, a bison bellowing. Very faint engraving marks on the nape of the neck, stronger on the dewlap.

On the right, another black bison, with only a few vague traces indicating an engraved or scraped outline.

These two Bison belong to the first plafond.

There are on the same plate various red signs, perhaps in connection with the second plafond; various graffiti: a 'tête de biche'

( this symbol is identified elsewhere in this paper as a red pectiform (i.e. comb shaped) sign - Don )

A little in front of the hump of the left bison; another between the two bisons, above the horns of the right one, a third in the vicinity, many other graffiti not very intelligible; several, to the left of the bellowing Bison, seem to contain still roughly executed hind heads.

Of the last ceiling, there remains only a small reclining Bison, placed on the right and the same height as the Bison on the right; it has been moved on the plate; the small bump whose forms it follows has been attacked and partially dissolved by the condensation of water.

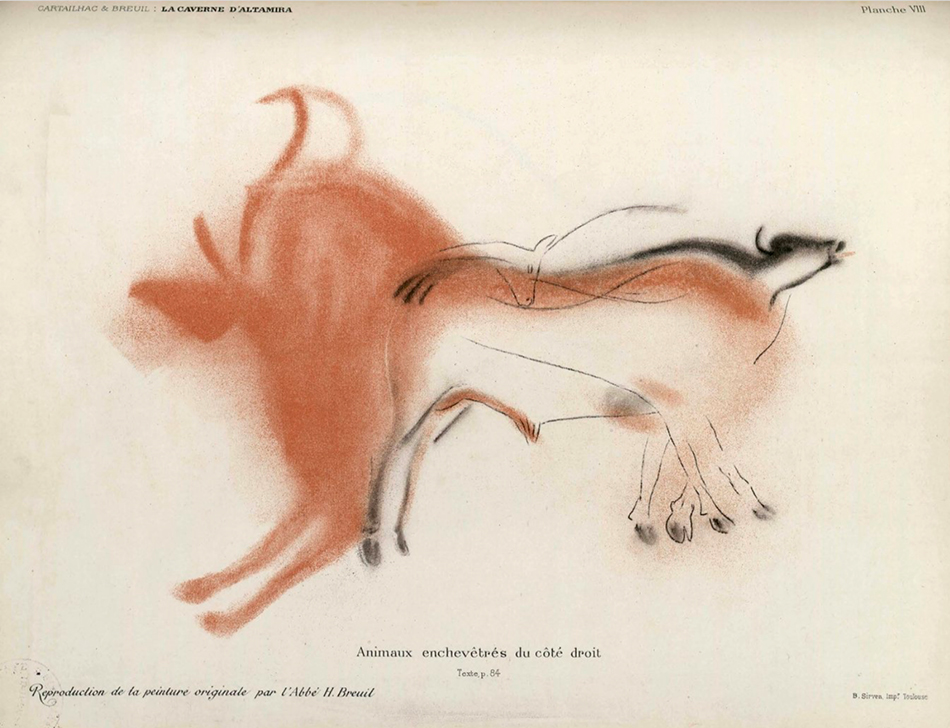

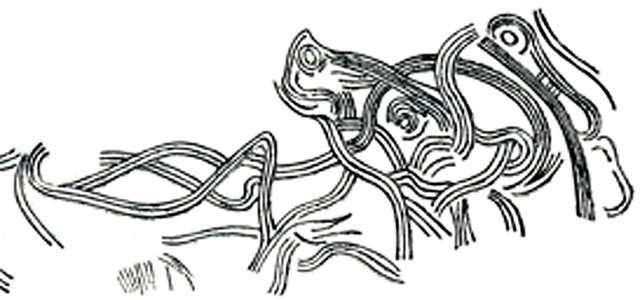

Entangled animals

Right side of the ceiling, Plate VIII

Dimension: 180 cm, from the nostrils of the stag to those of the Aurochs.

Four layers of ornamentation are visible on this plate:

First, a black animal, an aurochs, of which only the head and part of the loin remain.

Second, it has been cut by the execution of an animal, rather difficult to determine (Stag?) painted in flat red, which is of a very defective design. Several parts of the head are engraved: the eye, the nostril and the end of the muzzle, and the head; the lower jaw has detached itself from the ceiling, which in this place has a surface formed of raised scales like a crust ready to fall off.

Third, the outlines of a polychrome Stag have been painted in black at the expense of the previously erased Stag (?): many parts are only engraved.

Fourth, between the time when the flat red paintings were executed and the polychrome was begun, many finely traced drawings were etched over the red colour and under the black of the polychrome, except for one Stag's head, most of which are of very difficult interpretation.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

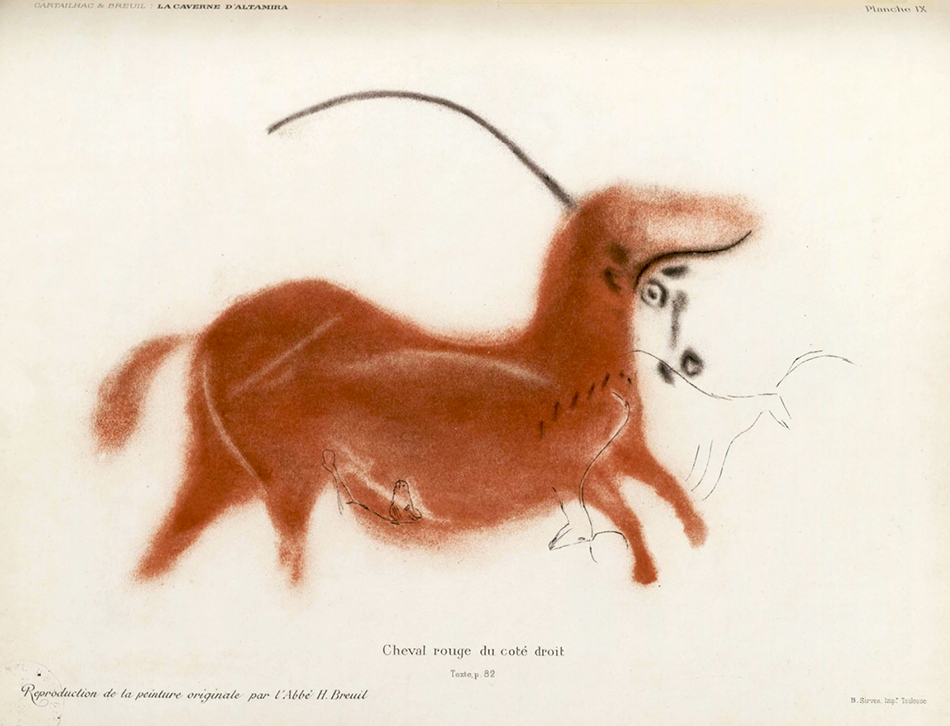

Red Horse on the right side.

Plate IX, dimension 1 metre from the base of the tail to the chest.

There are three layers of artwork on this plate:

First, the horse painted in uniform red, without engraved parts.

Second, drawings with numerous lines, interwoven, have been made over the colour of the horse; these are sketches of very unequal value: a horse on the belly, stags on the forequarters.

Third, the outlines of a polychrome Bison, which uses the red of the Horse, have been drawn in black; the head of the Horse has already been partially erased; the lower outline of the horse's head has been taken to trace the horn of the bison.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

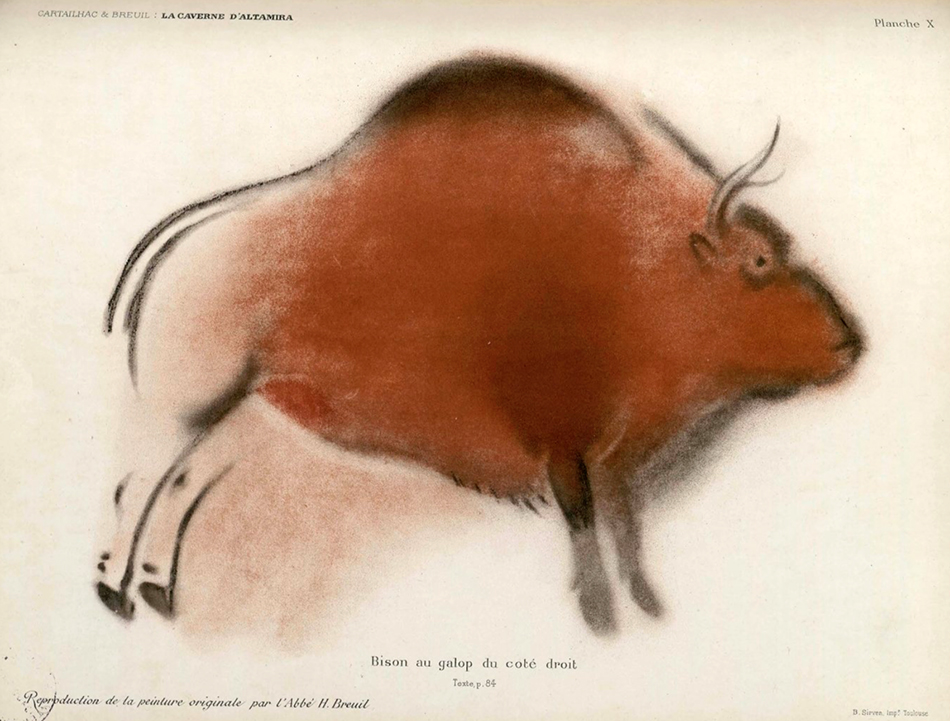

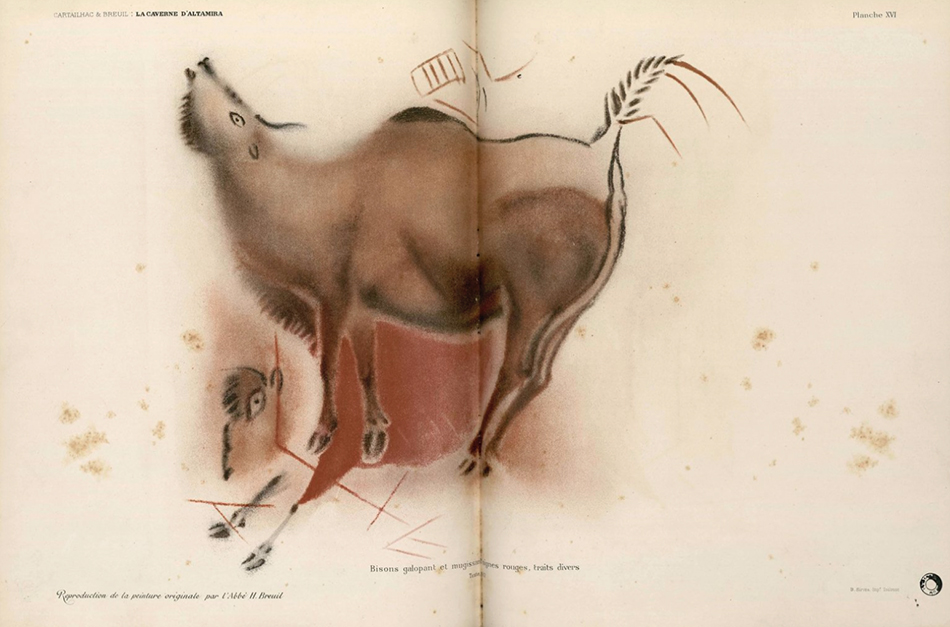

Galloping Bison

(right side of la plafond)

Plate X

Dimension: 175 cm from the buttocks to the nostrils.

There are two layers of frescoes on this plate (fig. 66); there was not enough time to show the first one; it is from memory that on the partial plan, a flat red horse's leg has been placed above the small of the Bison's back. A verification of the exact situation of the red horse was made during the second trip to Altamira; the superposition of this one is different, as the sketch published above (fig 60) allows us to see it.

The red horse was partially used for the body of the Bison; behind and under the belly of the latter, one can see the hindquarters and a leg of the horse. This one, like all the animals painted in flat red, is of a very poor design.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

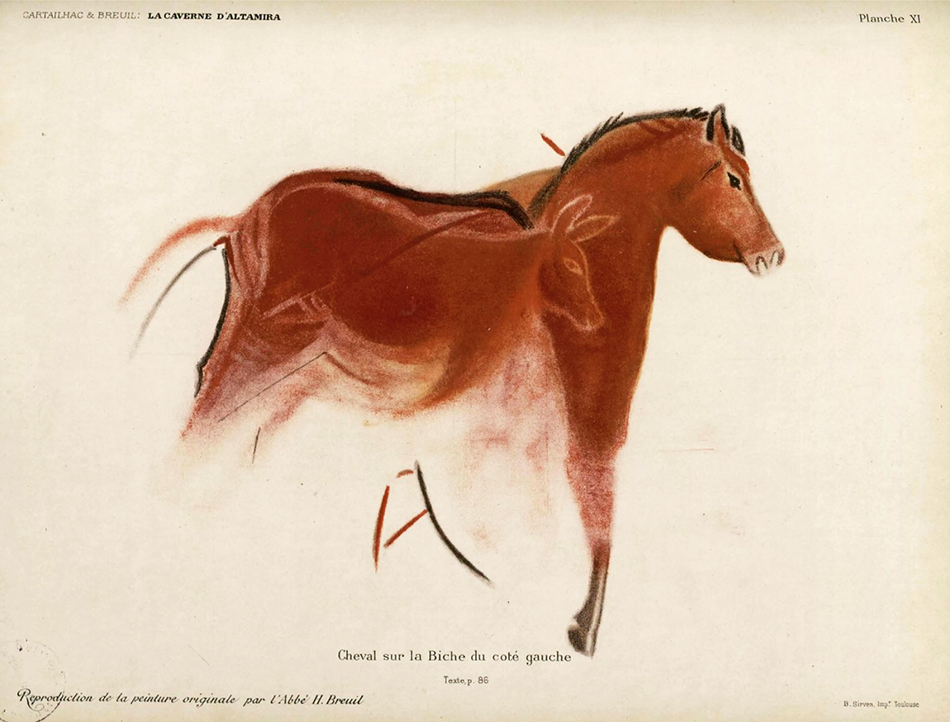

Horse and Doe

Plate XI

Size 160 cm, from tail to nose.

The hind was painted first in red, on an old background already painted in colour; the deep lines and contours of her drawing are covered with the red of the horse, as well as the whole hind, a little darker than the Horse; she seems to belong to the category of monochrome flat colours; her contours are too lightened on the board, and give the wrong impression that the Hind was made over the horse. The eye, mouth, nostrils and ears are low; the forehead, neck, dewlap, shoulders and front legs are weakly scraped (fig. 68).

The horse, a kind of pony, is unfinished and belongs to the polychrome paintings.

Engraved parts:

Eye, ear, outer contours of the mouth, mouth, nostril, chin, frontal line, scraped front part of the neck. Some traces of engraving at the hock, on the back. It can be seen around the mouth, as well as under the belly, that washing has been used to produce erasures and remove the colour of earlier animals (fig. 67).

The painting of the horse covers an engraving of a hind's head near her loins; under the belly, at some distance, is a drawing of an unintelligible man.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

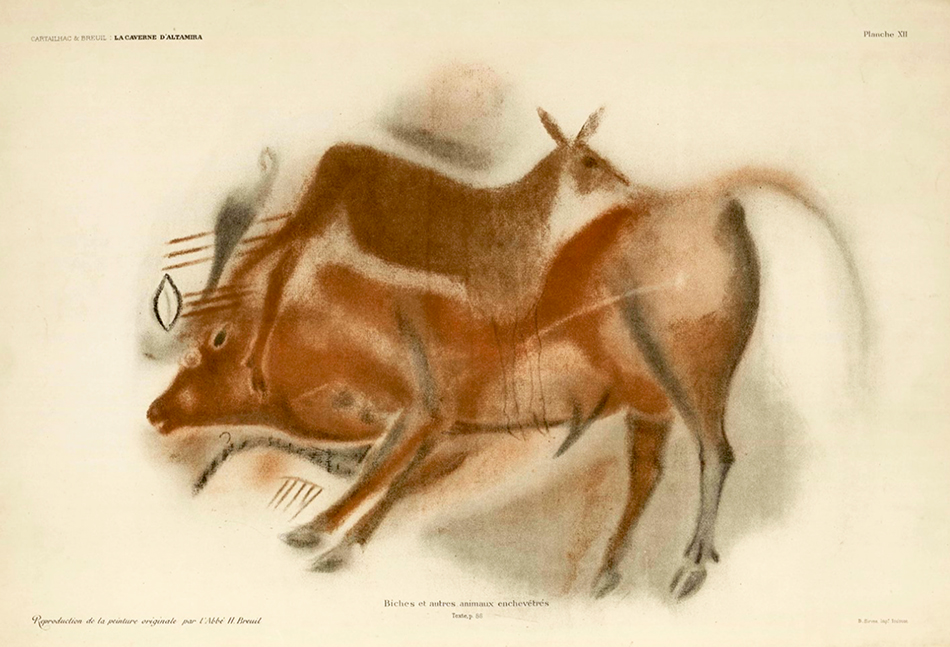

Entangled animals

Plate XII.

Dimension: 205 cm, from the nostrils of the red Hind's head (?) to the base of the Bison's tail.

This is the most difficult panel to decipher (fig. 69, 70). It seems that four successive layers of paint can be established:

First layer: Large black surfaces without appreciable shape, especially above the head of the little Hind, and between the legs of the Bison.

Second layer: Debris of a large Hind in a flat red colour. The nose on the left belongs to her; The eye is painted black; the ear of the bison was made of it afterwards.

The painting of this Doe covers an engraving of a Doe's head, hardly discernible; the contours of this head are finely engraved (nose, mouth, hairline);

Third layer: Small brown Hind, in a very weakened, uniform shade; the hooves of the hind feet are darker, indicating a tendency to mix the use of colours; the contours are deep and ragged over the red Hind of the second layer.

Engraved parts: Eye, ears, upper contours of the head and neck, front legs, belly line, part of the hind legs.

Scraped parts: Snout, lower contours of the head and neck, buttocks and back, belly surface. This last scraping is intended to produce an erasure; it was done at the expense of the Red Hind, of which only a few shreds remain. The dark hooves have been painted over the red colour. All around the brown Hind, there is a sort of aureole in light, obtained by a washing of the colour, and which frames the serious and scraped contours. The consequence of this washing was to make the colour penetrate, but very diluted, in the low lines.

Where there was no washing, but simply engraving, as on the limbs, red also penetrated into the features. It would therefore be necessary to suppose that the colour had been stamped and spread again, in order to execute the last animal, a bison.

Fourth layer: Unfinished bison. Only the hindquarters, the belly and the legs are finished. The eye is engraved over the red colour of the Doe of the second layer, on the front line of the Doe, which it begins. By masking it, the head of the Doe appears better; the eye of the Doe has been used as the ear of the buffalo.

Engraved parts: Eye, hind legs, horn, ear, nostrils.

Scraped parts: Area between the eye and the shoulder, the front legs are whole, the genitals, the tail, the buttocks and the small of the back.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

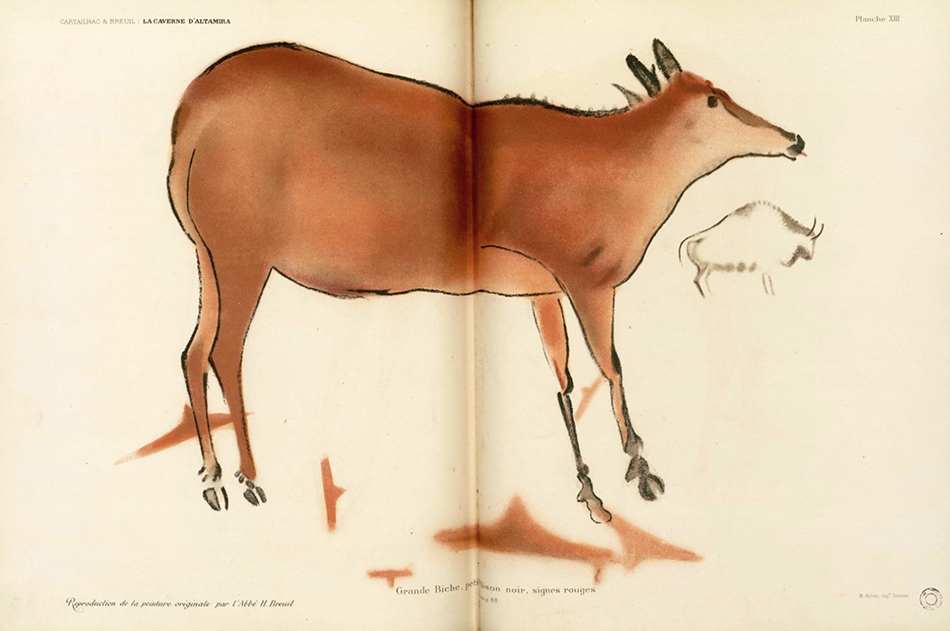

Plate XIII

Large doe, small black bison, red signs

Total length: 220 cm.

On the same plate (figs. 70, 71) there is a small bison painted in black, which belongs to the first decoration of the vault. There is no trace of lines drawn under the paint of this animal. On the second ceiling belong the boat shaped (?) signs which are of a flat red colour; they are here cut into and covered by the limbs of the large doe.

Prior to the execution of the last layer of paintings, either at the same time as the plain red figures, or a little later, but before the appearance of the polychrome frescoes, numerous line drawings, very shallow and mostly very tangled, were drawn on the ceiling. A human figure is seen above the small of the back (Fig. 41, no. 3), a second one is found at the shoulder (Fig. 42, no. 2), covered, as well as several others less complete or indecipherable, by the colour of the doe. Another exists under her front feet (fig. 43).

Engraved parts: Tear duct (strongly), nostril, mouth, eye, ears, jaw and neck edges, lower jaw.

Scraped parts: Right hind leg from buttock to fetlock; contours from tail to nape of neck, and from ears to nostrils; neck; part of front legs; ventral line; the chest has been lightened by the same means.

It must be observed that one ear, badly placed, has been incompletely erased by the artist. Dry, whitish concretions on the bottom of the buttock.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

The boat shaped signs above are similar to some extent to the Type Placard signs, which also occur at Cougnac, Pech Merle, and at Grotte du Placard.

The image at left shows a Type Placard sign and a man wounded by several spears, in red ochre. Height 75 cm, from Grotte du Pech-Merle, Lot. Probably from the Solutrean.

Photo and text: Michel Lorblanchet, via ma.prehistoire.free.fr/signe_au_pm.htm

Additional text: Don Hitchcock

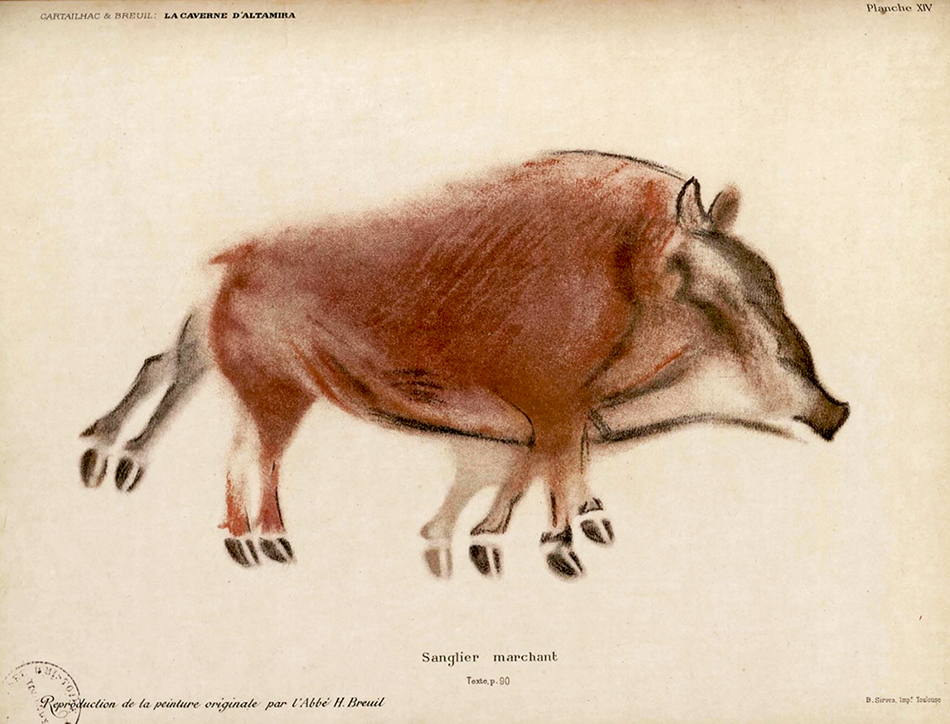

Walking Boar

Plate XIV

Dimension: 145 cm, from the tail to the snout.

A galloping boar had been executed first (fig. 73, 74): its black hind legs and part of its front legs are still visible. Although they are also black, it is not completely certain that they were not part of a polychrome; indeed, these legs have the appearance of the limbs of the figures in this last layer, which are entirely engraved and scraped. In this case, the body could have been used during the restoration that transformed its appearance: in this case, the eight visible limbs would belong to the base of the polychrome paintings.

The body, which follows the contours of a very softened hump, is quite faded. Its contours are somewhat blurred with the rocky background.

Engraved parts: Most of the front and rear legs, top of the snout.

Scraped parts: belly, buttocks, entire dorsal line (with solutions of continuity), tusk and mouth, chest.

Numerous graffiti in the vicinity: a hind under the belly (fig. 32, no. 1); huts behind the hocks, and behind the Boar in the direction of the large polychrome hind. Above the back, numerous fine graffiti; several bonshommes (fig. 41, no. 1, and 42, nos. 1 and 3) one larger, with stalactite on the head, above that of the boar. Several human drawings under the paint, poorly decipherable and interlocked: hands, heads, including a probable frontal one: two eyes and a nose.

Extremely weathered by the superficial decomposition of the rock due to the condensation of the vapour from the outside air entering the cave. As this figure is the closest to the entrance, it has suffered more than others from this condensation.

Engraved parts: Hind legs, some lines on the lower abdomen and the contours of the belly.

Parts scraped: The lower abdomen, a large part of the surface of the body from the head to the abdomen; a large area above and bordering the kidneys.

The attitude of this boar is not the flying gallop, no matter how long the posture is; indeed, the rear 'claws' still touch the ground, as they do not turn outwards, which would be necessary for the flying boar.

Various engravings in the vicinity: below, a bad doe's head; on the right, approaching daylight: engraving traces of a small whole cervid (Fig. 75 and 76).

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Wild boar at full gallop

Plate XV

Size: 160 cm from the base of the tail to the snout.

Extremely weathered by the surface decomposition of the rock due to the condensation of the vapour of the outside air penetrating in the cave. As this figure is closest to the entrance, it has suffered more than others from this condensation.

Engraved parts: Hind legs, some lines on the lower abdomen and the contours of the belly.

Scraped parts: The lower abdomen, a large part of the surface of the body from the head to the abdomen; a large area above the small of the back and bordering it.

The attitude of this Boar is not the flying gallop, whatever the elongated posture it affects; indeed, the hind 'claws' still touch the ground, as they do not turn outwards, which would be necessary for a flying Boar.

Various engravings in the vicinity: below, a bad Doe's head; on the right, approaching daylight: engraving traces of a small whole Deer. (Figs. 75 and 76).

The field of this panel is crossed by two large red, sinuous and parallel lines that cross several other animals and go towards the middle of the room. These are probably attributable to the phase of uniform red paint, as well as to the numerous and indecipherable line drawings underlying the paint.

Later, several animals were painted, following the procedures of polychrome painting. There was, perhaps, first of all, a horse, similar to the one in the picture above; I seemed to discern vaguely the faint outlines of its head on the boar's forehead; but they were too faint to be picked out.

In the third place, a boar (?) has been represented; its head, from the ears to the snout, measures 1 metre; the head is seen from a three quarters angle, for both nostrils are visible.

Engraved parts: Mouth, snout and its details, hair line, contours of the eye and pupil.

Scraped parts: Neck, part of the eye situated between the pupil and the external contour, a band running downwards, seem, at first sight, to limit the contours of a large leg, one can see on plate XXI that this clear scraped band, at the expense of another Bison, delimits the spine of an animal which seems to be a carnivore. The record of the engraved parts is incomplete on our drawing.

Finally, destroying the entire body of the preceding animal, a Bovid, which does not have the usual silhouette of a Bison, has been painted.

Engraved parts: Mouth and nostrils, eye, ear, left horn (faintly); hair on the withers, hump, around the tail, thigh; whole left foreleg, partial right.

Scraped parts: Beard, surface and front contours of the head; dorsal line to the loins; inner part of the tail; outer part of the thigh, partial contours of the hind legs, belly; surface of the front legs and interval between them. Line across the body (Fig. 77 and 78) .

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

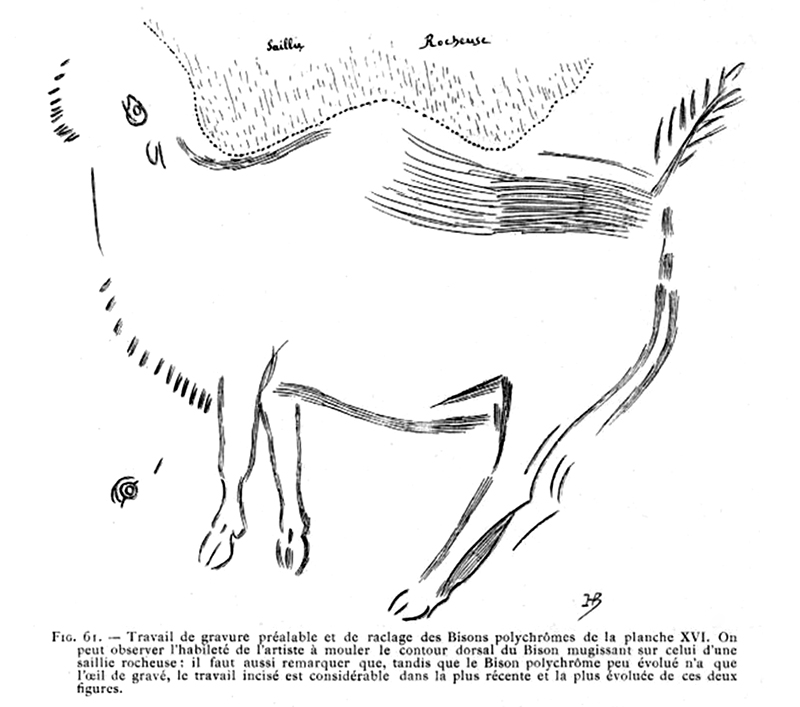

The process of creating some of Breuil's paintings

Figure 61

Preliminary drawing of the polychrome Bison on plate XVI. The artist's skill in moulding the dorsal outline of the bellowing Bison on that of a rocky projection can be observed: it should also be noted that little was changed between these two figures.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

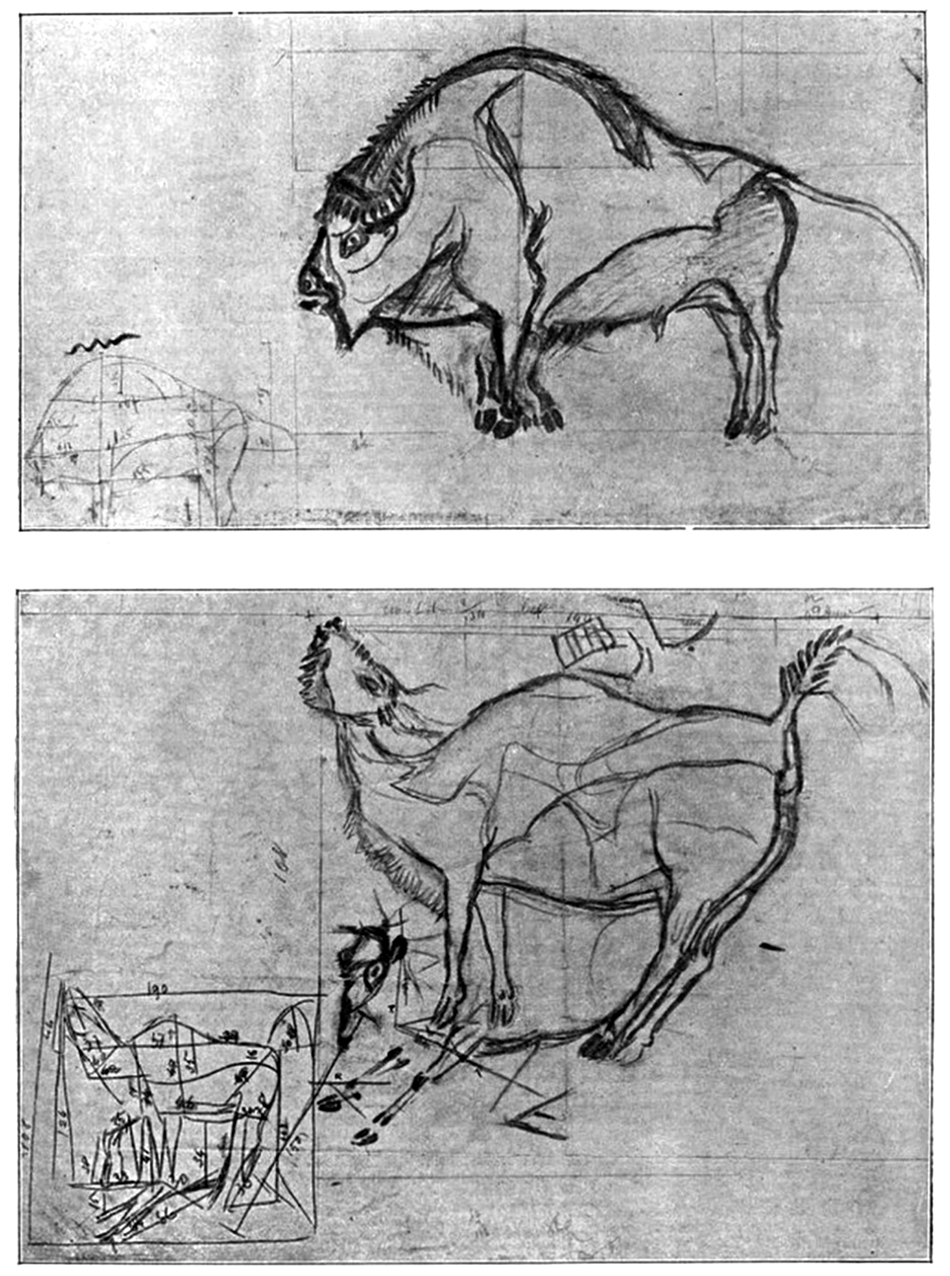

Figures 62 and 63

Pencil sketches used to draw two of the frescoes: on the left, a first sketch, made by hand, was used to note the measurements which were then transferred to the decimetre.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

The finished painting

Plate XVI

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

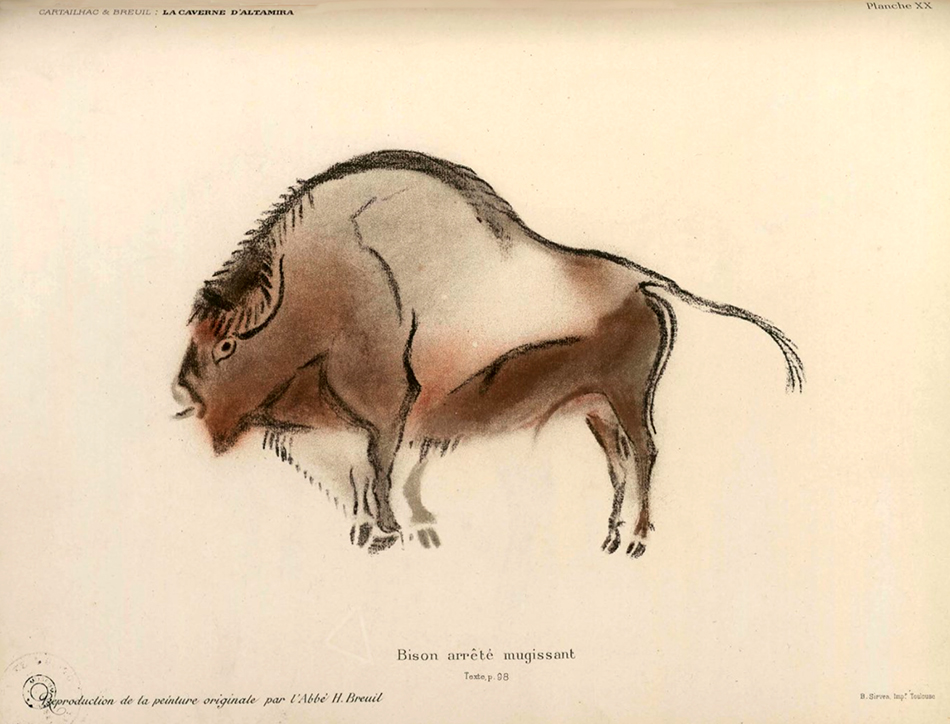

The finished painting

Plate XX.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

The finished painting

Another print, plate not named but the same as Plate XX.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

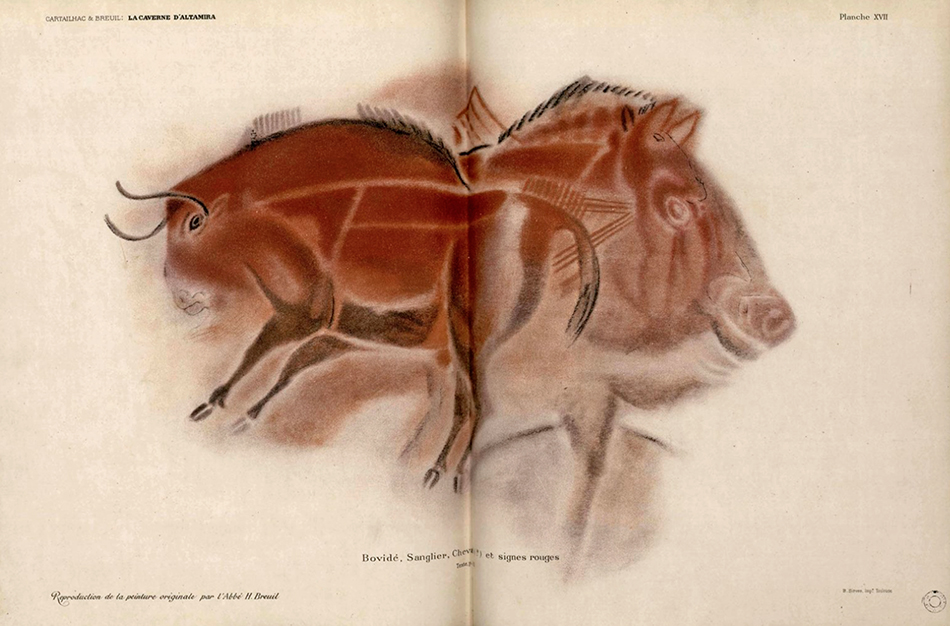

Plate XVII

Bovids and wild boar (?)

Distance between the muzzles of the two heads: 225 cm

The field of this panel is crossed by two large red lines, sinuous and parallel, which cross several other animals and go towards the middle of the room. They are probably attributable to the phase of uniform red paint and to the numerous and indecipherable line drawings underlying the painting.

Later, several animals were painted, following the procedures of polychrome painting. There may have been, first of all, a horse, similar to the one on Plate XI. The mane which appeared to be on the right may belong to it; I seemed to discern vaguely the faint outlines of its head on the forehead of the Boar; but they were too insecure to be picked out.

Thirdly, a boar (?) has been represented; its head, from ears to snout, is one metre long. The head is seen from three quarters, for both nostrils are visible.

Engraved parts: Mouth, snout and its details, frontal line, contours of the eye and pupil.

Scraped parts: Neck, part of the eye situated between the pupil and the external contour, band running downwards, seem, at first sight, to limit the contours of a large leg. One can see on plate XXI that this clear scraped band, in front of another Bison, delimits the spine of an animal which seems to be a carnivore. The record of the engraved parts is incomplete on our drawing.

Finally, destroying the whole body of the preceding animal, a bovid, which does not have the usual silhouette of a bison, has been painted.

Parts engraved: Mouth and nostrils, eye, ear, left horn (faintly); hair on withers, hump, around tail, thigh; left foreleg whole, right partial.

Scraped parts: Barbiche, surface and front outline of the head; dorsal line to the loins; inner part of the tail; outer part of the thigh, partial outline of the hind legs, belly; surface of the front legs and the interval between them. Line across the body (fig. 77 and 78).

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

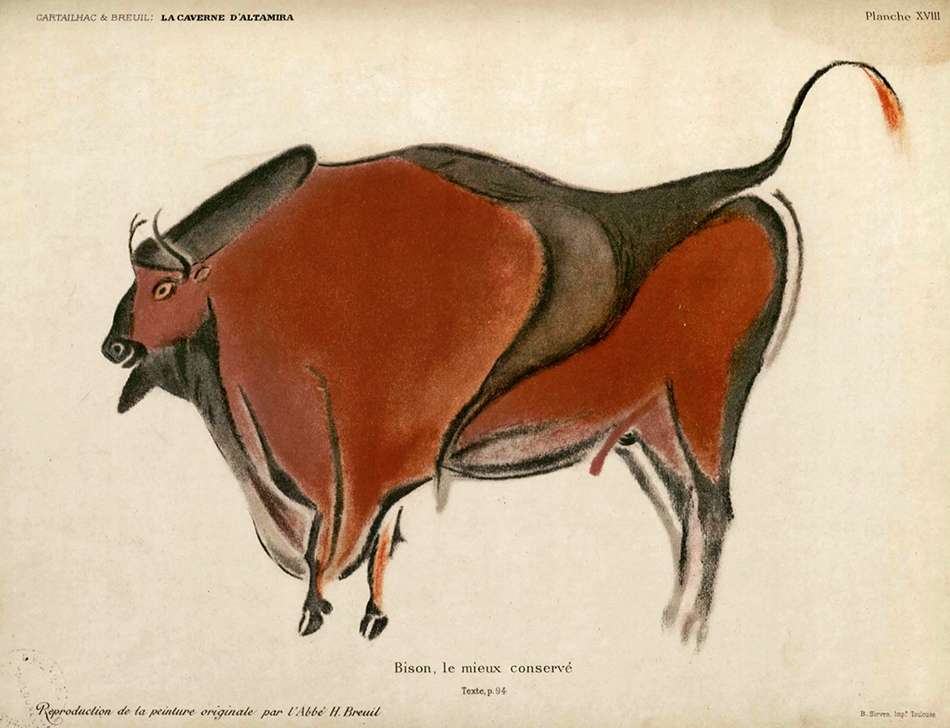

Plate XVIII

Bison, the best preserved

Distance from nose to the base of the tail: 150 cm

Traces of the first black-patterned plafond can be seen near the front legs, in the form of a series of small black signs, not very intelligible, and above, by the drawing of a Bovid horn.

The signs of solid red colour (2nd Layer), are very abundant around the Bison (see their drawing on figure 49 and plate V): in front of it, there is a sort of vegetal figure (?) there are two others behind; under the belly there is a large boat-shaped (naviform) sign. At various points, the polychrome bison is clearly superimposed on these red signs.

There are various unintelligible graffiti, and two huts (?) engraved, one near the front legs, the other further away.

Scraped parts: Buttocks, small of the back. (Fig 79 and 80).

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

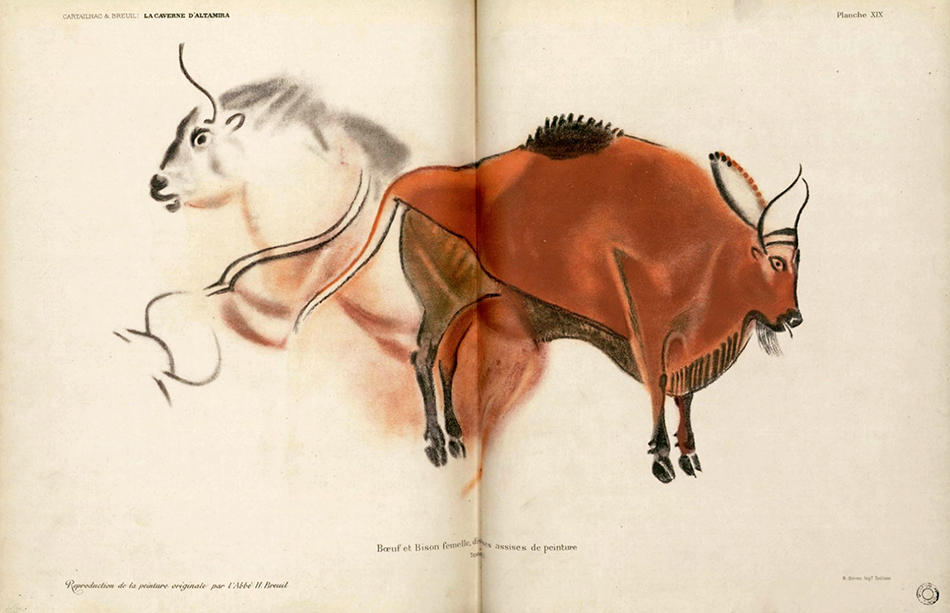

Plate XIX

Aurochs and female bison, various paint schemes.

Dimension of the female bison: 167 cm, from the nostrils to the base of the tail (inside)

( It is often difficult to tell which animal is being described here. So far as I can tell, both are seen as female, and the aurochs on the left is described as a cow - Don )

Various layers of paintings are represented on this plate:

1° Under the belly of the cow, small fragments of black drawings. Bovid's head painted in black, without any intervention from the engraver. Double sinuous line which seems to indicate the posterior contours (buttocks and hocks) of another Bovid, which was destroyed by the execution of the animals on plate XXI (?).

2° Large red tints which must have belonged to a large animal made in this colour, but of a completely impossible interpretation, it looks like a hindquarters, under the belly of the polychrome cow. There are other fragments of ancient frescoes, with engraving associated with the painting: such as an isolated eye, engraved and painted in front of the dewlap of the cow.

Finally, the cow, whose colour is wonderfully preserved, belongs to the group of polychrome animals.

Engraved parts: Eye, frontal line, nostrils, muzzle, mouth, tongue, hair of the goatee, muzzle, dewlap, lower contours of the neck, dewlap, right foreleg (partially) and hind leg on the same side (partially); hoof of the other hind leg; numerous small lines between the two horns and along the right horn; interval of two of the tufts of hair of the hump (deeply).

Parts scraped: Around the eye; outer contour of the left foreleg; front part of the right shoulder. One supernumerary foreleg not followed by the paint; parts of the belly, underside of the tail; some points of the hump and withers.

Washed parts : Defect of the shoulder from the knee to the elbow.

Observation: Active groove on the neck, which is altered by it. (Fig. 81 and 82.)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

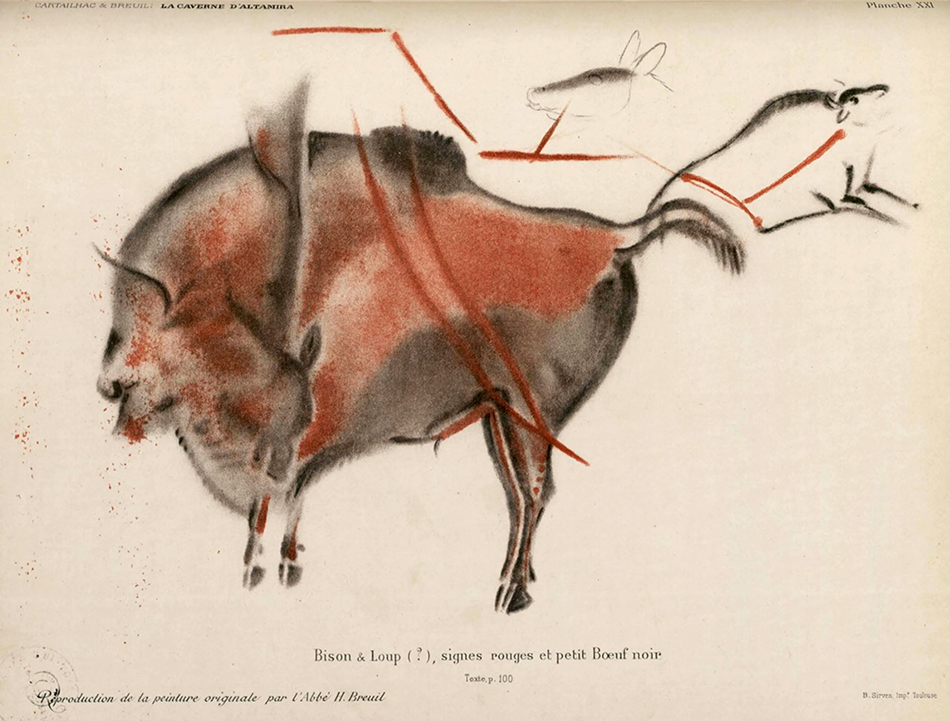

Plate XXI

Bison and wolf

Bison size: 130 cm, from nostrils to the base of the tail . Dimension of the small aurochs: 25 cm, from the buttocks to the nostrils).

1° A small Bovid in black is on the right of the plate; it is partially destroyed by the execution of the polychromatic Bison.

2° The field of this plate is crossed by two large lines, older than the polychrome animals, and which, starting from those of plate XVII, join the female Bison of plate XIX.

3° Engraved parts of the polychromatic Bison: Ear, anterior contours of the head, from the upper lip to the horns; part of the front legs; internal contours of the left hind leg; buttock, upper part of the tail head. Parts scraped : Barbiche; contours of the head, outside the carving; horn, the whole dorsal region, some points of the belly.

4° At the expense of the Bison, another animal has been started, which appears to be a Wolf; it is done by scraping, engraving and washing the colour of the underlying Bison; the dorsal line is engraved and scraped; the orcilla, partially engraved; the upper contours of the head scraped, the jaws, engraved, and the throat scraped. The rest is not executed; the light band on the back of this animal joins the outline of what might have been the leg of the boar on Plate XVII. (Figs. 85 and 86.)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

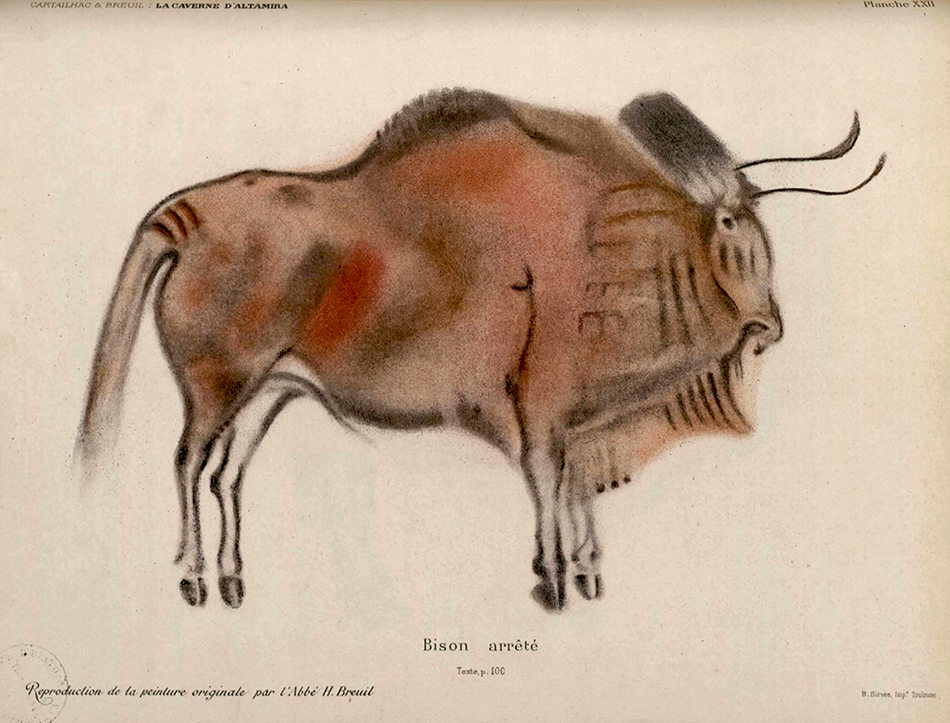

Plate XXII

Standing Bison

Dimension: 130 cm, from the base of the tail to the forehead.

1° Beneath the Bison on this plate are the traces of an enormous aurochs, about 3 metres long; it goes right across the room, with its back to daylight; it shows no other traces of paint than a few black touches on the nostrils, head, dewlap and hindquarters; large scrapings still delineate a large part of its contours quite clearly. Three different oval eyes have been engraved on its head: a large one and two smaller ones above.

2° Unintelligible graffiti on the hind legs of the polychrome;

3° Standing bison in polychrome, very shaggy; feet rather altered.

Engraved parts : One of the horns; pupil; hair on the forehead; outline of the muzzle, nostril, mouth; limits and hair on the dewlap; part of the forelegs; lower abdomen.

Scraped parts: Tail, contours of loins, thigh, belly; limits of dewlap.

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

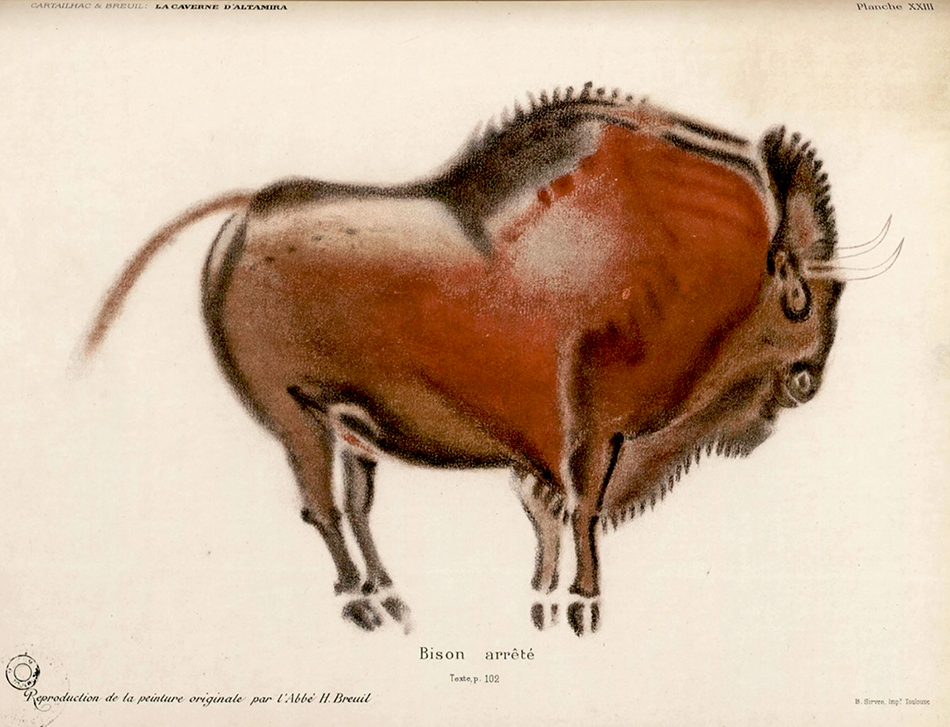

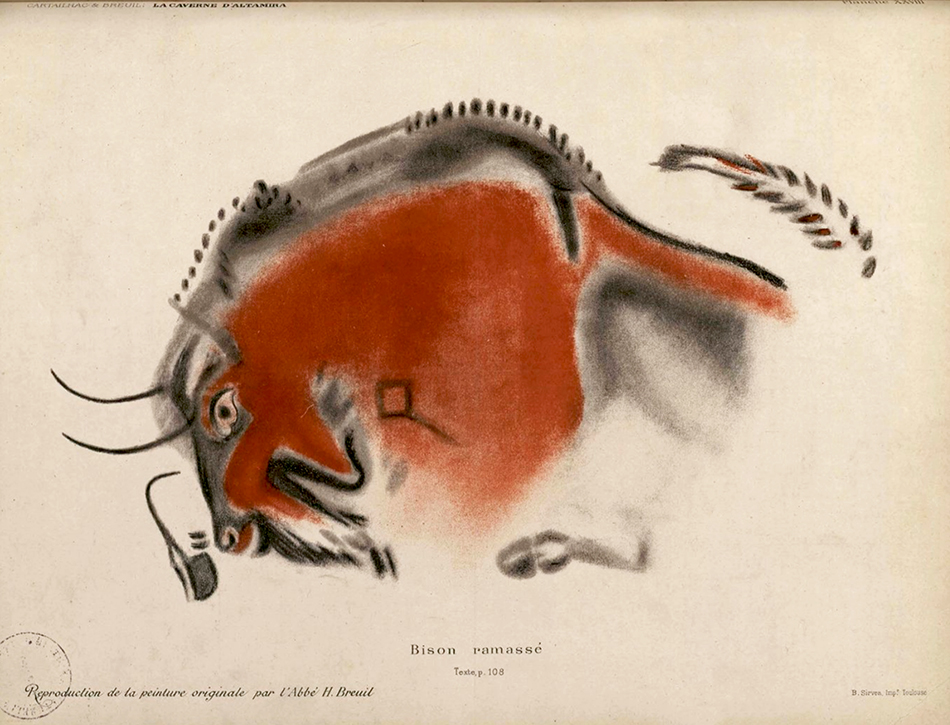

Plate XXIII

Standing Bison

Size: 150 cm, from buttocks to forehead

Under the paint, in the neck of the Bison, an engraved head of a doe, quite good. A bad graffiti of a Horse's head and other jumbled lines are above, between this painting and the wall, where there are still some small red marks.

The bison has been modelled on a smoothly contoured hump, the steepest edge of which follows the withers and loins of the animal, while the other side blends in insensitively with the flat part of the surfaces. The paint has further accentuated the natural relief with its shades. The forehead is outlined by a crack.

Engraved parts: The horns are not painted, but only engraved; the eye, the ear, the nostrils, the mouth, the muzzle, the goatee, the hair on the dewlap, the nape of the neck and the hump; most of the four limbs, the outline of the belly.

Scraped parts: Nape of the neck, goatee, chest, attachments of the right foreleg; outline of the belly, interval between the hind legs, underbelly; the whole of the back outline; various points of the dorsal line. (Fig. 89 and 90.)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

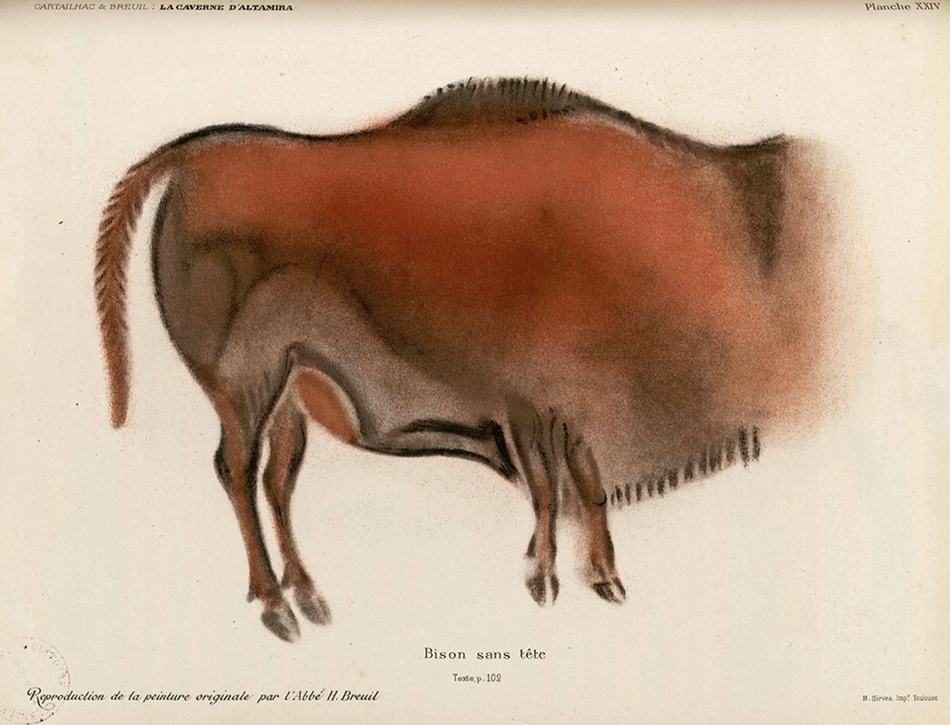

Plate XXIV

Headless Bison

Size: 120 cm, from the base of the tail to the nape of the neck

Between the tail and the wall there is an engraving of a Horse's head, looking to the left, and of two Hinds' heads, bad, one deeply engraved.

Above the withers is a pretty horned head, quite deeply engraved, and above the nape of the neck, a poor Bovid head, facing the entrance to the cave.

Deeply engraved parts: Nose, dewlap hairs; two forelegs and inner contours of hind legs; tail and hump hairs.

Scraped parts: Tail, outline of loins, thigh; double ventral line; goatee, withers; limits of lower belly; surface of hump; double part of hindquarters and shoulder.

The head seems never to have been painted, as there is no trace of neck, and the rock is not particularly weathered. The hind feet are much altered; the tail has been painted by superimposing red lines on black ones. (Figs. 91 and 92).

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

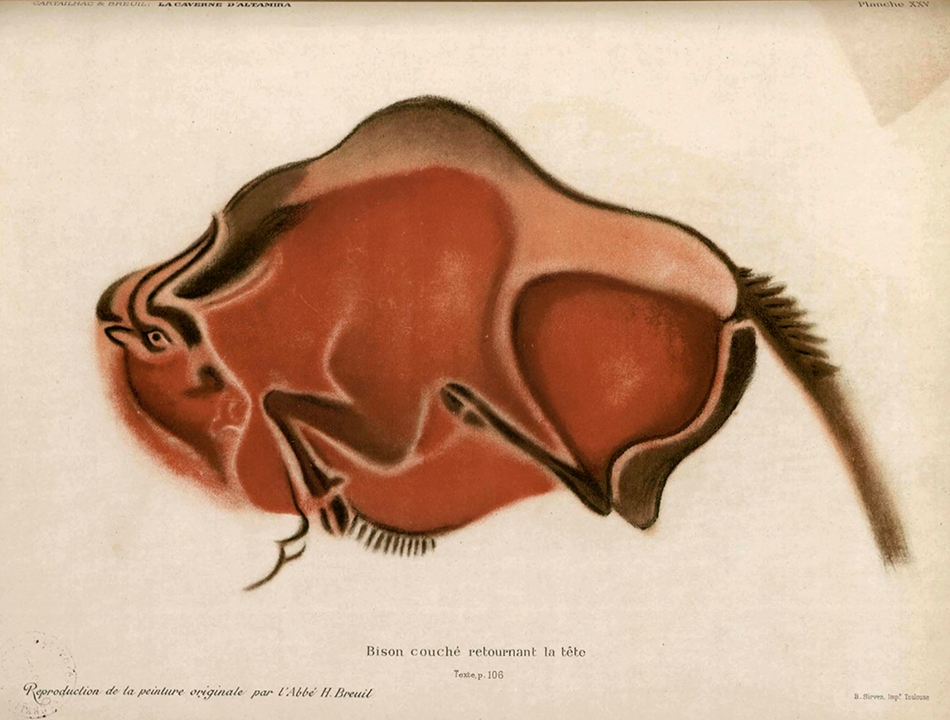

Plate XXV

Bison lying down and turning its head

Size: 160 cm from the underside of the tail to the ear

The ornaments painted in red are represented by three red dots which run between the snout of the boar (Plate XVI), and the hocks of this bison. Engravings are abundant in the vicinity; one notices a hut above the nape of the neck; an engraved head of a hind, partially painted in black, under the hock; under the polychrome painting two heads of hinds; one at the dewlap, turned towards the back of the room (bottom of the plate), another, in real relief, so deep is the line, across the start of the tail.

The head and the thigh follow the accidental shapes of the rocky surface; the head occupies a projection whose steep edges are followed by the forehead and the muffle of the bison, so it stands out very well against the flat background of the body; the thigh is intelligently placed on a hump with very soft contours to which it owes a very pronounced relief.

Engraved parts: Nostrils (strongly); pupil of the eye (finely); interstices of the tufts of hair on the tail and chest (strongly); ears in half relief.

Scraped parts: Entire contours of the animal; frontal line, mouth, horns; hump, whip of the tail. The rump and almost the entire outline of the limbs have been lightened by scraping and perhaps washing. (Figs. 93 and 94.)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

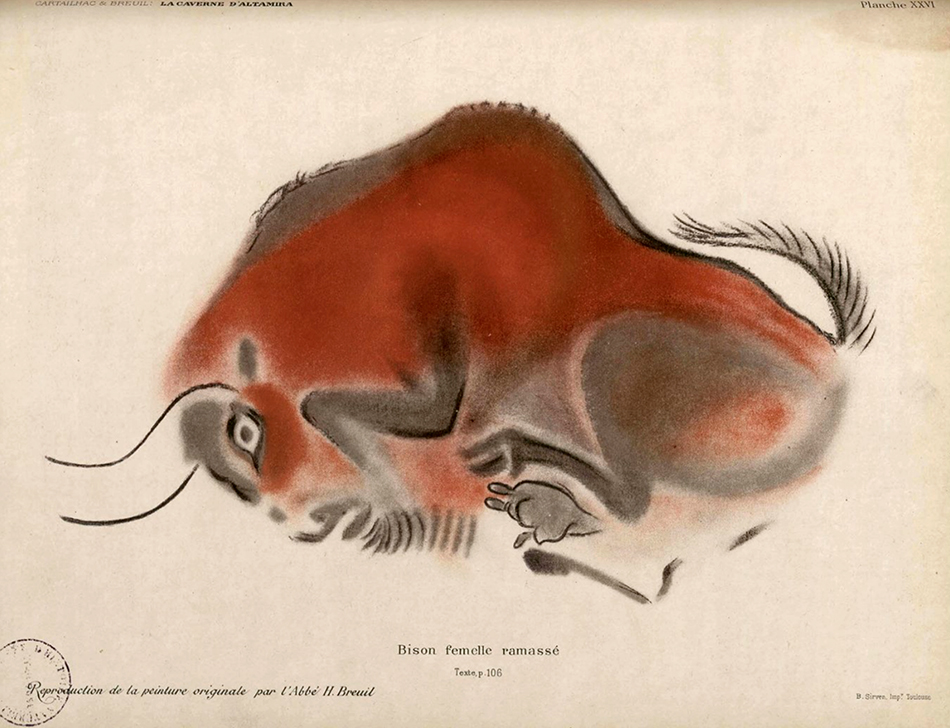

Plate XXVI

Female bison hunched as though to spring

Size: 145 cm from from forehead to base of tail

This bison was made on a large bump in the ceiling; condensation, which is very active on these bumps, has greatly altered certain parts, especially around the chest.

The contours of the hump are very smooth between the nape of the neck and the loins, and very abrupt, on the contrary, everywhere else.

Engraved parts: Pupil, tail and dewlap hair.

Scraped parts: The gap between the tail and the body; the surface of the loins; the entire dorsal contour from the loins to the nape of the neck; the ear, the horns; the surface of the dewlap, the contours of the left hind leg; a few points on the thigh and the shoulder (Figs. 95 and 96.)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

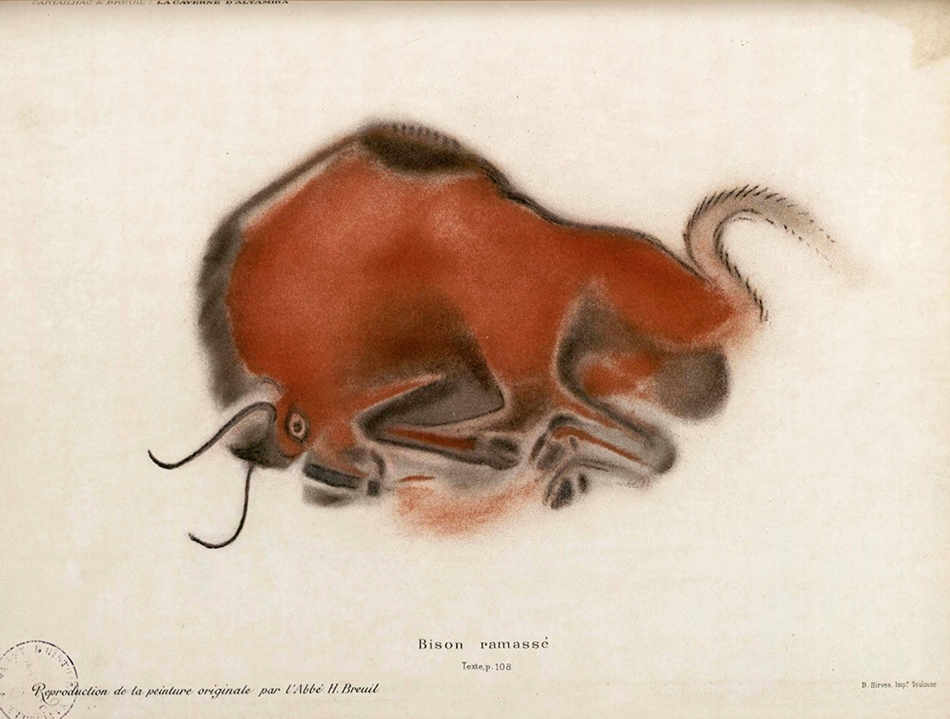

Plate XXVII

Bison hunched as though to spring

Size: 140 cm from from forehead to base of tail

1° Head of a Hind engraved in the horns;

2° Bison occupying a large bump in the ceiling with fairly regularly steep contours. Only the horns and the tail are outside the bump.

Engraved parts: Horns, some tufts of hair from the hump.

Scraped parts : Frontal line, nostrils; upper contours of neck, dorsal surface almost entirely, axis of tail. Contours of the left foreleg and the hoof of the left hind foot. The contours of the limbs, the eye, appear to have been washed rather than scraped. (Figs. 97 and 98.)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Plate XXVIII

Bison hunched as though to spring

Size: 150 cm from from forehead to base of tail

The spine of the great Bison reported elsewhere (PI. XXII, p. 100) passes over this animal. This animal occupies a large hump in the ceiling, part of which has completely disintegrated; its contours are very abrupt; the black contours of the animal (tail, dorsal line, nape of the neck, horns, frontal line and right paw) are outside the hump; the latter is flatter towards the head and tail.

Engraved parts: Withers, eyebrows, eye, nostril, right hoof and leg.

Parts scraped: Surface of the muzzle, and contours; mouth, small of the back, thigh. (Figs. 99 and 100.)

Note: In animals which have been very much affected by humidity due to condensation, part of the weak engravings may have disappeared, the paint still remaining. The bumps are particularly attacked by the dew which settles there in fine droplets; these, sliding along their declivity, gather in larger drops, and end up forming, at the points of relief, liquid plates which penetrate the surface of the limestone and transform it into a real "cream".

My drawings of these bumps are not decals, impossible because of the high relief; they are not views; the declivity of the bumps shortens the view of all contours. I began by making these in their place and in their exact relations, so that each part appears in the overall view; in the cave they can only be seen successively.

(H. B.)

Photo and text: Cartailhac et Breuil (1906)

Additional text: Henri Breuil

Replica of the Altamira ceiling, at the Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España

Photo: José-Manuel Benito

Permission: Public Domain

Ortho-image of the polychrome ceiling at Altamira. Produced by the National Geographic Institute.

Photo: Corruchaga et al. (2003)

Deer of La Hoya, the pit, the middle chamber of Altamira.

Photo:

de la Campa et al. (2001)

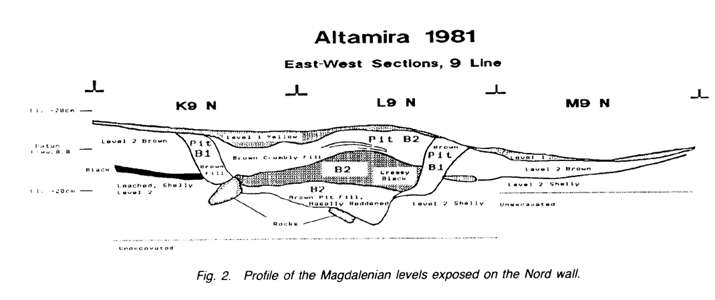

This replica of Altamira as shown during the reproduction of the paintings re-creates the original cavern space as it was during Palaeolithic habitation rather than as it is today: that is, natural rock falls, supporting walls, paths, and other arrangements made in modern times have been suppressed. By applying computerised modelling to the cave’s topography, more than 40 000 sample points per square metre were measured and shaped; the reproduction has an accuracy of one millimetre. The paintings have been reproduced using the same techniques and natural pigments employed by Palaeolithic artists. Thus high technology and artisan techniques were combined to achieve the best results.