Back to Don's Maps

Tools from the stone age

Hand Axes

A modern reproduction hand axe beautifully crafted by Harm Paulsen, master flint knapper from Schleswig.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

A hand axe can be a thing of beauty. It is surprisingly difficult to make, and requires a great deal of forward planning, knowledge of how stone can be shaped, and knowledge of how to create a relatively thin object, but with a sharp cutting edge.

Forming it into roughly the desired shape is relatively easy, but getting it thin, symmetrical, and with sharp edges all round is a highly skilled operation, and is a process which takes a long time to master.

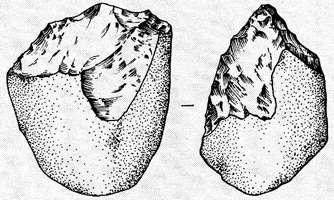

'Choppers', the oldest worked stone implements.

Gabarones, Botswana, 2.5 million - 1 million BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

'Choppers', made from millions of years ago, are relatively easy to make. Select a suitable stone from a river bed, strike it several times against a larger rock to split off flakes, and in a few minutes you can have a serviceable tool for cutting up an animal carcase, helping with the skinning process, and breaking bones to get at the marrow.

But they are heavy, not necessarily easy to hold in the hand, and usually not very sharp, since their working edges are short, and not often equipped with sharp angles.

For that you need a Hand Axe.

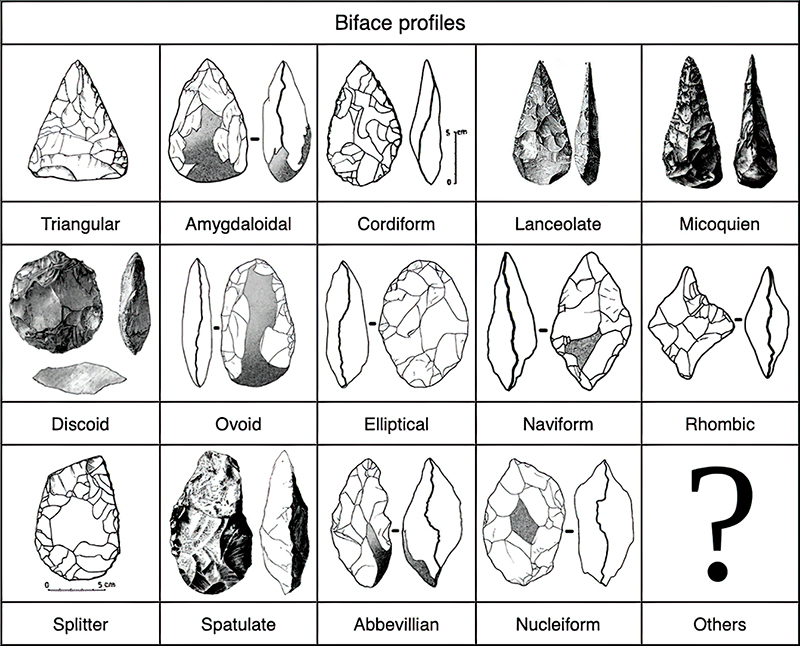

Acheulean Hand Axes / Bifaces

This is a very useful diagram showing various types of Biface (Acheulian) handaxes.

Note that there is very little difference between the Lanceolate and Micoquien profiles, and individual handaxes may be very difficult to assign to one or the other of these two profiles.

Photo: Wikipedia

Acheulean Hand Axes

Elliptical Profiles.

The first hand axes (also known as bifaces) are usually called Acheulean / Acheulian, named after the site of gravel quarries in the suburb of Saint-Acheul in Amiens, France.

Acheulean stone tools are the products of Homo erectus, ancestor to modern humans. Not only are the Acheulean tools found over the largest area, but it is also the longest-running industry, lasting for over a million years until relatively recent times.

These hand axes are from St Acheul, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Acheulean Hand Axe

Cordiform (heart shaped) Profile.

Palaeolithic, circa 500 000 BP

This is a classic quartzite Acheulean handaxe from North Africa, found in a dry watercourse, a small tributary of the Draa river, near Tan Tan,

at N 28.23233, W 10.59947.

Dimensions 220 mm x 115 mm x 60 mm.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2016

Source: Private collection

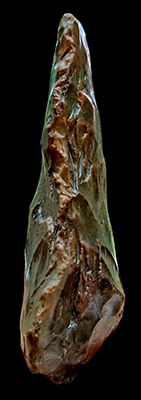

Acheulean Hand Axe

Narrow Lanceolate Profile.

1.4 - 1.2 million years old

Found in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.

Handaxe made of a hard green volcanic lava (phonolite) with a compact texture. Elongated tear drop form with slight ancient damage at tip. Regular edge all round, both faces slightly convex.

Catalog: 1934, 1214.49

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2017

Text: Card, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum

Source: Exhibition by the British Museum at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra

Acheulean Hand Axe

Cordiform (Heart shaped) Profile.

Circa 1 500 000 BP - 300 000 BP, from S'baikia, Algeria.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

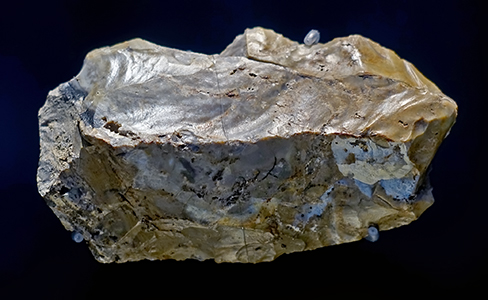

1 400 000 BC - 200 000 BC

Faustkeil, Handaxe

This hand axe is of Acheulian culture, and is the oldest piece in the August Kestner Museum in Hannover.

( It appears to be of a material similar to silcrete, and is a coarse grained example with bedding lines and inclusions, only suitable for crudely made large tools such as this handaxe or chopping tool. - Don )

Catalog: Eastern Sahara / Bayuda desert in present day Sudan

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Museum August Kestner, Hannover

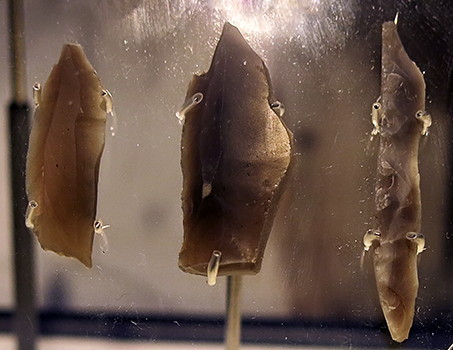

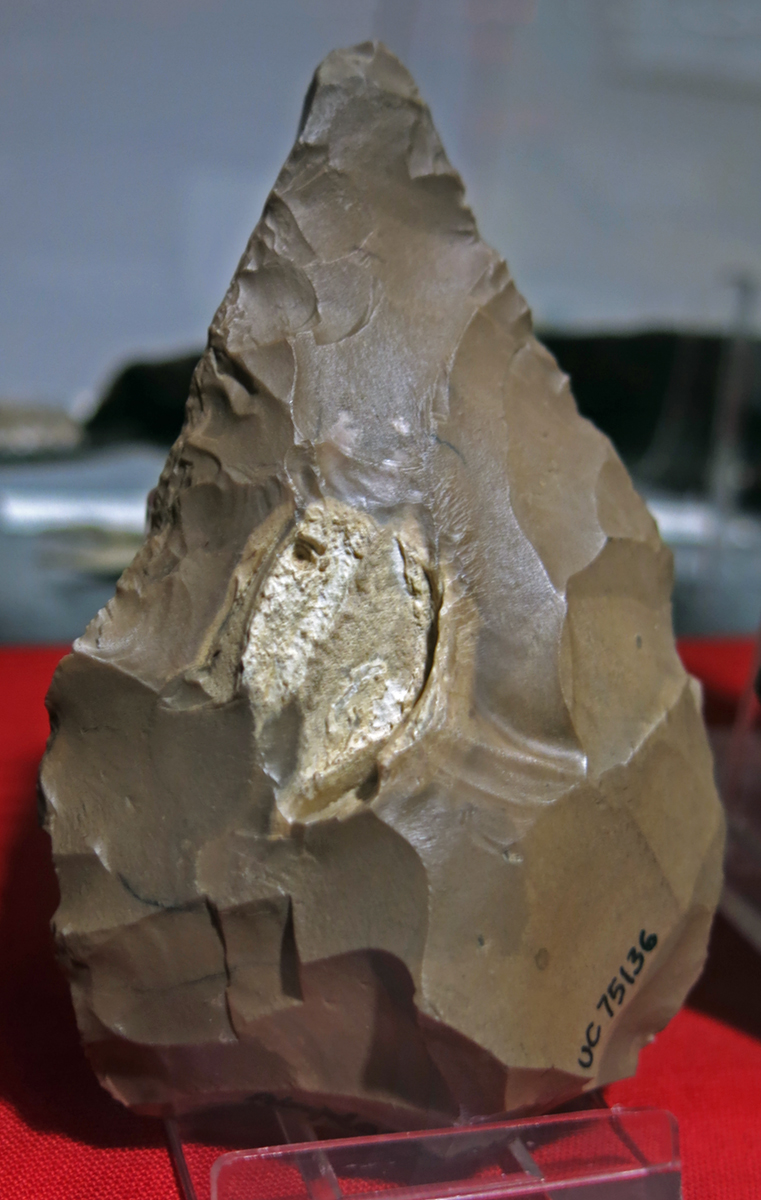

Retouched flint flake, handaxe?, Abydos

Age 400 000 BP - 350 000 BP.

Length 98 mm, width 63 mm.

Accession Number LDUCE-UC75136

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Petrie Museum

Flint handaxe, Acheulean; with cortex butt. From El Amrah, Nile level.

Age 400 000 BP - 350 000 BP.

Length: 135 mm

Accession Number LDUCE-UC13575

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Petrie Museum

Acheulian Handaxe

(Acheulian - Old Palaeolithic : about 1800 000 BC - 200 000 BC; typical are large bifacially flaked handaxes, picks and cleavers; people lived as gatherers of wild plants and scavengers/hunters of animals)

Age of this specimen 400 000 BP - 350 000 BP.

Flint handaxe, developed Acheulean, with cortex butt. Found 9 miles NNW of Naqada at 1400 ft above sea-level, on a hill-top plateau.

Lanceolate bifaces like this one are the most aesthetically pleasing and became the typical image of developed Acheulean bifaces. Their name is due to their similar shape to the blade of a lance. Bordes defined a lanceolate biface as elongated (l/m > 1.6 , i.e. maximum length / maximum width > 1.6) with rectilinear or slightly convex edges, acute apex and rounded base, 2.75 < l/a < 3.75. L/a is maximum length / distance from point of maximum width to base and expresses the position of maximum width in relation to the length.

They are often globular to the extent that it is not a flat surface, at least in its basal zone, with m/e < 2.35 , m/e meaning the ratio of maximum width / maximum thickness and expresses the thickness relative to width, or 'refinement' of the axe.

They are usually balanced and well finished, with straightened edges. They are highly characteristic of the latter stages of the Acheulean – or the Micoquian, as it is known – and of the Mousterian in the Acheulean Tradition (closely related to the Micoquian bifaces).

Length 174 mm

Accession Number LDUCE-UC13577

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Petrie Museum

Flint handaxe, developed Acheulean, with cortex butt one side.

Lanceolate bifaces like this one are the most aesthetically pleasing and became the typical image of developed Acheulean bifaces. Their name is due to their similar shape to the blade of a lance. Bordes defined a lanceolate biface as elongated (l/m > 1.6 , i.e. maximum length / maximum width > 1.6) with rectilinear or slightly convex edges, acute apex and rounded base, 2.75 < l/a < 3.75. L/a is maximum length / distance from point of maximum width to base and expresses the position of maximum width in relation to the length.

They are often globular to the extent that it is not a flat surface, at least in its basal zone, with m/e < 2.35 , m/e meaning the ratio of maximum width / maximum thickness and expresses the thickness relative to width, or 'refinement' of the axe.

They are usually balanced and well finished, with straightened edges. They are highly characteristic of the latter stages of the Acheulean – or the Micoquian, as it is known – and of the Mousterian in the Acheulean Tradition (closely related to the Micoquian bifaces).

Found by Seton-Karr at a low level at al-Ga'ara SE of Dendera.

Length 151 mm, Accession Number LDUCE-UC13579.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Petrie Museum

Additional text: Wikipedia, ikarusbooks.co.uk/resources/Lsarc.pdf

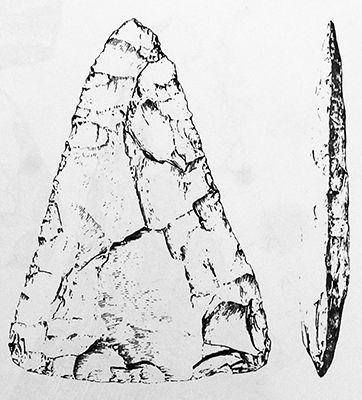

Acheulean Hand Axes

Lanceolate Profiles.

Left:

The Gray's Inn Lane Hand Axe is a pointed flint hand axe, found buried in gravel under Gray's Inn Lane, London, England, by pioneering archaeologist John Conyers in 1679. The hand axe is a fine example from about 350 000 years ago, from the Lower Palaeolithic, and probably made by Homo erectus, who made most of these sorts of hand axe.

Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/10134001, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Right:

Another Acheulean hand axe was discovered by John Frere in the 1700s, when he investigated a four metre deep pit (dug by brickworkers) at Hoxne, in England.

Photo: Johnbod

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Acheulean Hand Axe

Lanceolate Profile.

Palaeolithic, 300 000 - 30 000 years ago

Hand axe, Maastricht.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Faustkeile, Handaxes

Left: from the Bissing collection.

Catalog: Flint, Thebes, ÄS 1211, ÄS 1489

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

Acheulean Hand Axes

Nucleic (resembling a knapped core) Profile.

Palaeolithic, 300 000 - 30 000 years ago

From Rhenen.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Acheulean Hand Axe

Elliptical Profile.

Palaeolithic, 300 000 - 30 000 years ago

Hand-axe, Moerslag.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

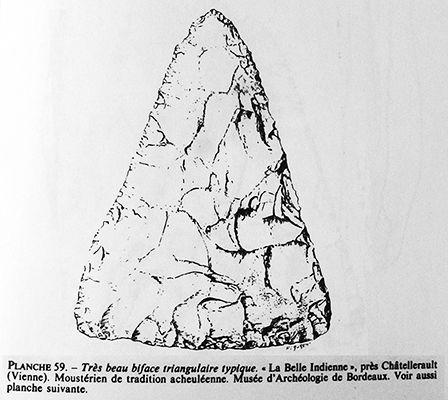

Neanderthals and the Moustérien de tradition acheuléenne (MTA) handaxes / bifaces

Neanderthals also made handaxes indistinguishable from the Acheulean handaxes. Since we also use the word Mousterian for the Neanderthal culture, after the classic Neanderthal archaeological site of Le Moustier near Les Eyzies in France, the classic Acheulean handaxes made by Neanderthals are given the name Moustérien de tradition acheuléenne (MTA).

This superb Neanderthal handaxe below is in this tradition.

Mousterian MTA biface hand axe, made of flint. This is an important piece from the Départment Vienne near Châtellerault (La Belle Indienne), as may be seen from the inscription on the axe.

Triangular profile.

Length 172 mm, width 126 mm, thickness 27 mm.

This handaxe is seen by many collectors as the non-plus-ultra for the Moustérien de tradition acheuléenne (MTA) bifaces.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Catalog: 60.1563.1

Source: Original, Musée d'Aquitaine à Bordeaux

Mousterian MTA biface hand axe.

Lanceolate Profile. Note however that this handaxe has been ascribed to the Micoquien, probably because of its asymmetry.

Circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Neanderthals were master stone knappers. They possessed a sense of aesthetics and an intuition for the right material, as may be seen from their handaxes.

In Heidenschmiede, Heidenheim, district Heidenheim. there were numerous stone tools made from fresh water quartzite. This is a material very similar to flint, and outcrops only a few kilometres from the site.

Length 148 mm, width 71 mm.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

Neanderthal hand axe in the Acheulean tradition, but made from a flake.

Flint (jasper) tool from Frieburg. Mousterian culture, circa 80 000 BP.

Elliptical profile.

Small Mousterian ovate hand axe / scraper.

Note the large flake taken out for a thumb grip. There are many neanderthal tools (and even some upper palaeolithic tools) with this feature.

The blank was struck from a flint (jasper) core and bifacially worked in the handaxe tradition.

Worked on both sides, this piece still stands in the long tradition of early handaxes, but is characterised by careful restoration of a flat surface. It may have been used as both a scraper and a handaxe.

In the case of fairly small tools such as this, it is often difficult to determine if it is primarily a Breitschaber / Blattschaber (wide / blade scraper) or Faustkeil (hand axe).

It may have been used as a handaxe in the morning, and a scraper that afternoon. Not for nothing is the classic handaxe known as the 'Swiss Army Knife' of Palaeolithic tools. Many millions were made, and used for many purposes - cutting, scraping, smashing bones to obtain the marrow, or choppers for cutting up carcasses or cutting down small trees.

Similar tools are also known from other European sites and are referred to as the Mousterian culture after the French site of 'Le Moustier' (Dordogne / France). This culture was of Neanderthal origin.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008, 2015

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

An overview of the development of stone tools, from Acheulean Hand Axes to late Neolithic arrow heads

This case shows the full sweep of stone tools, from the very old to some of the youngest.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Palaeolithic, 300 000 - 30 000 years ago

(3) Points, Rhenen.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Palaeolithic, 300 000 - 30 000 years ago

(4) Scraper and Levallois-flake, North Sea.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Late Palaeolithic, 13 000 - 9 600 years ago

(6) Blade core, Magdalenian, St.-Geertruid.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Late Palaeolithic, 13 000 - 9 600 years ago

(7) Points, Hamburgian

(8) Federmesser group, Drunen

(9) Points, Ahrensburgian

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Late Palaeolithic, 13 000 - 9 600 years ago

(10) Tools, Magdalenian, Eyserheide.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Mesolithic, 10 800 - 7 000 years ago

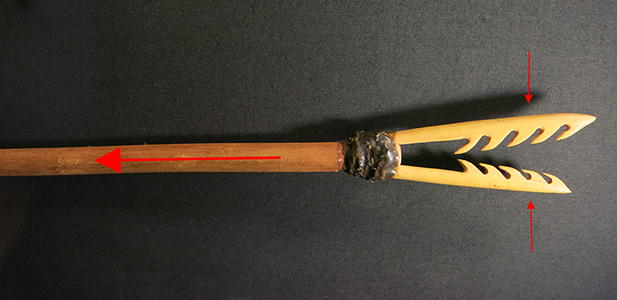

(11) Bone harpoon, replica.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

The above is a fine example of the use of microliths. Their use was not because of a lack of good flint, but because they were far more effective at dropping prey, because of the shock they provided from the wound they made. The wound was large and lacerated, and the blood loss and associated organ damage disabled even large prey.

A weapon such as this would take a long time to make, from the number of flints knapped, to the crafting of the bone with a pair of suitable grooves, to making the birch glue, (a mixture of resin, beeswax and ochre was also used as a glue) and to fitting everything together into a beautifully made killing machine. Although this is labelled as a harpoon, points of similar construction were used fixed to spear/dart shafts. See in particular Pétillon et al. (2011) and also Wilkins et al. (2014)

Mesolithic, 10 800 - 7 000 years ago

(13) Points, early Mesolithic

(14) Points, middle Mesolithic

(15) Points, Late Mesolithic

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Mesolithic, 10 800 - 7 000 years ago

(15) Points, Late Mesolithic

(16) Inventory of hunting camp, Budel

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Mesolithic, 10 800 - 7 000 years ago

(12) Tranchet axe, Oldemarkt

(13) Points, Early Mesolithic

(14) Points, Middle Mesolithic

(15) Points, Late Mesolithic

(16) Inventory of hunting camp, Budel

(17) Hafted points, replicas

Early Neolithic, 7 300 - 6 900 years ago

(18) Bandkeramik arrowheads, Elsloo

(19) Bandkeramik tools, Elsloo

(20) Bandkeramik blade core, Elsloo

Middle Neolithic, 6 200 - 5 400 years ago

(21) Blade core, St. -Geertruid

(22) Scrapers, Rijckholt

(23) Arrowheads, Michelsberg culture

(24) Pointed blades, Michelsberg culture

Late Neolithic, 4 900 - 4 000 years ago

(25) Arrowheads, tanged, Veluwe

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Late Neolithic, 4 900 - 4 000 years ago

(26) Arrowheads, barbed, Veluwe

(28) Dagger, Rhomigny-Lhért flint

(29) Dagger, Grand-Pressigny flint

(30) Dagger, Scandinavian type

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Late Neolithic, 4 900 - 4 000 years ago

(26) Arrowheads, barbed, Veluwe

(27) Arrowheads, triangle and hollow base

(28) Dagger, Rhomigny-Lhért flint

(29) Dagger, Grand-Pressigny flint

(30) Dagger, Scandinavian type

Bronze Age-Early Iron Age, 4 000 - 2 600 years ago

(31) (far right) Sickle

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

From the oldest to the youngest tools

Currently the first stone tools are dated somewhat earlier than the first evidence for the genus Homo. The oldest tools are 2.6 million years old and come from Kada Gona in Ethiopia. They are attributed to Australopithecus garhi. For the 2 milllion year old tools from Kanjera in Kenya, transport routes of more than 12 km have been ascertained. Like the 1.8 million year old stone tools from Koobi Fora, also in Kenya, they belong to the Oldowan culture, which in eastern Africa comprised only simple choppers and chopping tools.

Text above: Vienna Natural History Museum, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

Tools from Kenya, 2.5 million years old.

Facsimiles

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

'Choppers', the oldest worked stone implements.

Gabarones, Botswana, 2.5 million - 1 million BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Chopper, 1 000 000 BP - 2 600 000 BP.

From Merimde-Benisalame, Egypt.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Olduvai stone chopping tool

2.0 - 1.8 million years old

Found in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.

This stone chopping tool is the oldest object in the British Museum and one of the oldest known tools made by our earliest human ancestors. Its discovery in northern Tanzania with fossil remains of an extinct human species proved that both human life and technology began in Africa. Tools like this were particularly useful in breaking open bones to obtain the marrow fat inside. High in calories, marrow was an important component in the development of the human brain.

Chopping tool of basalt from Oldowan, Olduvai Gorge. The removal of a large flake from the top of the cobble provide a striking platform for the removal of three flakes which form a well defined regular edge. A second less satisfactory edge has been formed by removals along the opposite side of the first striking platform. The rest of the cobble retains its natural surface.

Length 93 mm, depth: 72 mm, thickness 88 mm.

The cobble may have been used as a source of flakes for use in light duty tasks or as a chopping tool or both.

Findspot: Olduvai Gorge, CK III

Exhibited: 2016-2017 08 Sep-29 Jan, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 'A History of the World in 100 Objects'

Collected by: Dr Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey

Catalog: 1934, 1214.1

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2017

Text: Card, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum

Source: Exhibition by the British Museum at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra

Chopper and flake.

Koobi Fora, Kenya.

Circa 1 900 000 BP - 1 600 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Vienna Natural History Museum, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

These flakes from volcanic rocks, struck from nuclei, have sharp edges.

Dmanisi, Georgia, 1.8 million BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Pebble tools possibly made and used by Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, or early Homo erectus.

From Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, around 1 800 000 BP.

Catalog: E3368, E1153

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

Chopper

Olduvai, Tanzania.

Circa 1 800 000 BP - 1 500 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Vienna Natural History Museum, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

1.

Chopper from Waltenheim-sur-Zorn, Bas-Rhin, period of Homo erectus, donated by M. Ehretsmann.

Found in 1989.

( Readers should note that this artefact was found at or near the surface, not in situ. It had apparently been brought to the surface by ploughing - Don )

Quartzite, height 74 mm, width 52 mm, thickness 43 mm.

Its distal part has three successive groups

of removal:

A. Two primary removals (No. 1 and 2) created a free edge inclined at approximately 55°.

B. Two secondary removals (no. 3 and 4) resulting either from the shaping of the piece or from its use.

the present inclination of the cutting edge, i.e. close to 90° in relation to the edge of the pebble.

C. The keels (no. 5) are located on the side of the main edge of the tool, and are used to create a sharp edge.

This tool corresponds to the unidirectional cutter of Biberson's classification (1961) (type 12

of Ramendo (1963) ).

2.

Chopper from Achenheim with single removal in quartzite or quartzite sandstone. Found in: Rhine grey sands.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée Archéologique Strasbourg

Text: Ehretsmann (1991)

Choppers and a chopping tool from Achenheim, loessière Hurst ( a loess hill? - Don )

At the site of Achenheim (Bas-Rhin, Alsace, France) near Strasbourg, thick loess deposits are found fossilising a former terrace of the Rhine and Bruche rivers which have been affected by neotectonics (recent earth movements).

The four loess deposits comprise a continual sedimentary sequence which spans the Late Pleistocene and a part of the Middle Pleistocene. Achenheim has a typical profile which can be correlated with the loess stratigraphy of Western and Central Europe.

Italicised text above: Heim (1982)

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Musée Archéologique Strasbourg

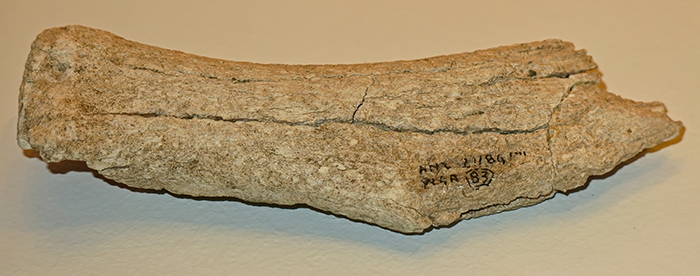

Termites are a protein-rich and easily accessible feed source. These bones were used for 'termite fishing'.

Pushing them into the termite mounds has left longitudinal striations on the surfaces of the bones. By using a little spit on the bones, the termites stuck to the tools.

Acid from the termites has etched the ends of the bones.

Swartkrans and Sterkfontein, South Africa, 1.8 to 1.0 million years old.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

One of the oldest known products of the human hand is this simple tool of pounded lava . It was found in the lowest stratum of the famous Olduvai site in East Africa. Front and side view.

Photo: Sklenar (1988)

This chopper, made from a small stone, comes from the limestone cave Shandalya or Shandalia I, in the former northern Yugoslavia, the oldest archeological site in Europe. The tools are equivalent to those from Dmanisi, and the deposits of mammalian fauna are similar. (Gabunia, 2000)

Photo:

Sklenar (1988)

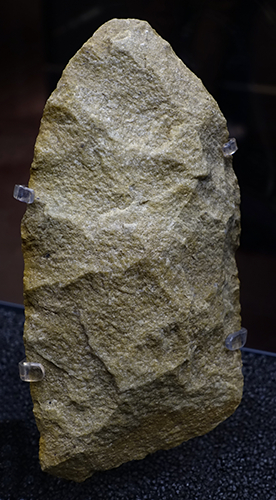

Olduvai handaxe

1.4 - 1.2 million years old

Found in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania.

A new form of tool known as a handaxe first appears in the archaeological record about 1.6 million years ago. Although made from stone, handaxes are often so well made that they look nothing like the natural lumps of rock from which they are produced. Using a stone hammer, the maker has carefully struck flakes alternately from both faces around the entire edge, making it thinner at the tip and thicker and heavier at the bottom. This may seem simple but requires a skilful use of force. The edges are sharp and regular, suitable for use as cutting tools.

Out of Africa

The ability to engage with and transform the environment enabled early human ancestors to adapt to new and different places. Around a million years ago handaxes were widespread — except in the Americas and Australasia — reflecting the first gradual migration of early human populations out of Africa.

Handaxe made of a hard green volcanic lava (phonolite) with a compact texture. Elongated tear drop form with slight ancient damage at tip. Regular edge all round, both faces slightly convex.

Findspot: Olduvai Gorge, CK III (Africa, Tanzania, Arusha (region), Olduvai Gorge)

Exhibited: 2016-2017 08 Sep-29 Jan, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 'A History of the World in 100 Objects'

Collected by: Dr Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey

Catalog: 1934, 1214.49

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2017

Text: Card, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum

Source: Exhibition by the British Museum at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra

Hand axe, 1 500 000 - 300 000 BP.

From the Algerian Sahara.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Hand axes typified the material culture of Homo erectus, which is called the Acheulian culture after the site St Acheul in France.

This hand axe (two different views) is from Pajitan, in Java, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

These hand axes are from St Acheul, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Hand axe from St Acheul, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Acheulian hand axe, 1 500 000 BP - 300 000 BP, from Fort Zouérat, Mauritania.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Acheulian hand axes, 1 500 000 BP - 300 000 BP, from Khyad, India.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Acheulian hand axe, 1 500 000 BP - 300 000 BP, from the Algerian Sahara.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Acheulian handaxes probably used by Homo erectus.

From Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, near Nsongezi in Uganda and Kariandusi in Kenya, around 1 400 000 BP - 700 000 BP.

Catalog: E1157, E3760, PAE_1147

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

Hand axes from Swanscombe, Thames valley, England, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Acheulian hand axe, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Found on the foreshore of the River Thames, UK.

Dimensions 120 mm x 95 mm.

Above, views of the two sides and the base.

This interesting small handaxe appears to be of jasper. It has been very well made, shaped by taking out relatively large flakes.

The shape bears some resemblance to a Micoquien hand axe, but it is quite symmetrical front to back.

It is very similar to the Swanscombe handaxe on the left, above, in shape, knapping method, and quality of flint/jasper.

The estimated age is based on general considerations and this marked similarity to the Swanscombe handaxe.

Photo: Courtesy Ben Mankowitz 2021

Source: Ben Mankowitz

Acheulian hand axe, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Found on the foreshore of the River Thames, UK.

Dimensions 133 mm x 102 mm.

This (rolled) handaxe is very similar to the one above from the same findspot.

It appears to be of flint, and like the one above has also been very well made, and shaped by taking out relatively large flakes.

The estimated age is based on general considerations and its marked similarity to the Swanscombe handaxe above.

Photo: Courtesy Ben Mankowitz 2021

Source: Ben Mankowitz

Hand axes from Swanscombe, England, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Hand axe from Nanterre, France, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Another view of the hand axe above from Nanterre, France, 1 500 000 BP - 200 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

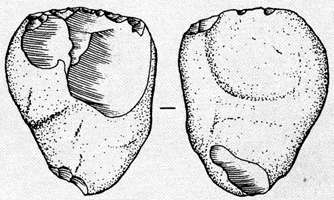

Bola, circa 1 400 000 BP.

Bolas are often used in threes, connected by leather thongs to a central point, and are thrown to entrap the legs of game animals, bringing them down to be killed by hunters.

Photos of two facsimiles of the same object from 'Ubeidiya, Israel.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Facsimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

This is a superbly made modern bola. It is a work of art.

Photo: Paracordist

Source: http://www.bushcraftuk.com/forum/showthread.php?t=83896

Chopper, a tool made quickly and easily from a river pebble by striking off a few flakes to make a useable edge, circa 1 400 000 BP.

From 'Ubeidiya, Israel.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Facimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

A hand axe from Olduvai Gorge, over 1 million years old.

British Museum 1934,1214.59

Taken at the GLAM event on 13th October 2011 at the British Museum.

Photo: Discott

Permission: licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Hand axe from Abbeville, St Acheul, 800 000 BP - 300 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neues Museum, Germany

Text: © Card at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DE)

Hand axes from Abbeville, St Acheul, 800 000 BP - 300 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neues Museum, Germany

Text: © Card at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DE)

Splitting wedge, 800 000 BP.

From Gesher Benot Ya'aquov , Egypt.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

The handaxe is the absolute symbol for the Stone Age, and no wonder - they were made from 1 000 000 BP to 50 000 BP, and billions were manufactured.

They were not easy to make well. In numerous individual steps, the handaxe was carefully and precisely shaped to the right form, and with sharp edges.

Both sides shown, from: Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel, 800 000 BP, apparently original.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Nucleus or core, 800 000 BP.

From Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Abschlag, or flake ca 500 000 BP.

(This piece might be possibly better labelled as debitage, useless material struck from a core on the way to making a well made tool, although as Ralph Frenken (pers. comm.) has pointed out, museum staff have put considerable effort into piecing it together, which argues for classification as a useful tool - Don )

From Meisenheim, Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Quartzite handaxe, circa 500 000 BP.

Hochdahl, Stadt Erkrath, Kreis Mettmann

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Quartzite cleaver probably used by Homo heidelbergensis.

( Cleavers were used much as a butcher would use a meat cleaver today, to quickly chop through a joint or a bone, or to cut a large slab of meat from a leg or shoulder - Don )

From Kalambo Falls, Tanzania/Zambia border, around 500 000 BP to 300 000 BP.

Catalog: E3652

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

Acheulian hand axe, 500 000 to 400 000 BP, from Chelles, France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Acheulian hand axe, 500 000 BP - 300 000 BP from Saubrigny, France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Scraper, 500 000 BP - 300 000 BP.

Scrapers were used primarily for preparing hides stripped from game, but may also have been used as knives.

From Ried, Bavaria, Germany.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Facsimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

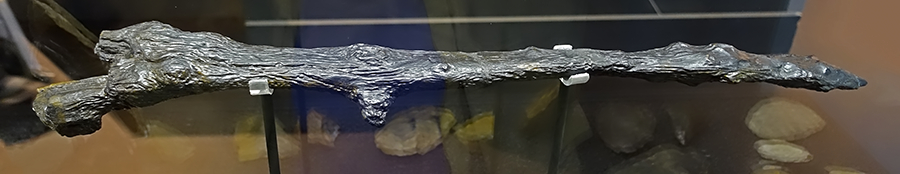

Wooden digging stick probably used by Homo heidelbergensis.

From Kalambo Falls, Tanzania/Zambia border, around 500 000 BP to 300 000 BP.

Cast. Original in the Natural History Museum, England.

( presumably in a controlled atmosphere vault in storage at the same museum this cast is displayed for public viewing - Don )

Catalog: E4547

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

Made of yew, this spear point is the oldest preserved wooden spear in the world. Its owner would probably have used this as a lethal weapon, stabbing prey at close range to generate enough force to pierce the animal's skin.

Taxus sp., Clacton, Essex, England, around 420 000 BP.

Catalog: E1183

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

(left) Almond shaped flint biface hand axe from the Lower Palaeolithic, collected at Bertranoux: Commune Creysse, Aquitane, Dordogne.

Length: 227 mm, width 124 mm, thickness 52 mm.

(right) Lanceolate shaped flint biface hand axe from the Lower Palaeolithic, collected at Saint-Sulpice-d'Eymet, Commune Saint-Sulpice-d'Eymet, Aquitane, Dordogne.

Length: 285 mm, width 132 mm, thickness 70 mm.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Musée d'Aquitaine à Bordeaux

Acheulian hand axe, ca 400 000 BP, from Hoxne, England

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Acheulian hand axe, ca 400 000 BP, from Amiens, France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

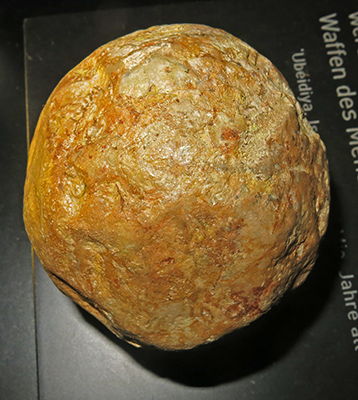

Hammerstone, used for knapping flint, ca 400 000 BP.

From Mühlheim-Kärlich, Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Quartz and quartzite tools in Travertine limestone, circa 330 000 BP - 310 000 BP.

The travertine was formed as the result of the solution and redeposition of existing limestone in a karst environment, and at least 25 well-identified stone tools have been found in the travertine, dating from the time of its formation 330 000 years ago, during a warm period of the middle Pleistocene.

Kartstein, Stadt Mechernich, Kreis Euskrichen

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Additional text: http://www.georallye.uni-bonn.de/kartstein_bei_satzvey

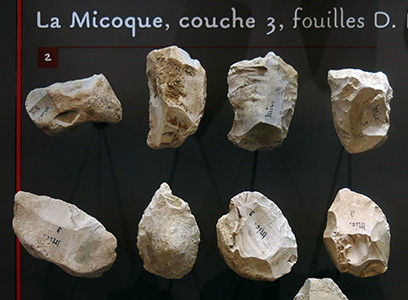

Racloirs, scrapers, circa 320 000 BP, from la Micoque, France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Originals, Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

Throwing stick. These are designed to rotate in the air when thrown, and are used to bring down small animals.

Schöningen, Niedersachsen, Germany, ca 300 000 BP.

Schöningen is famous for the Schöningen Spears, four ancient wooden spears found in an opencast lignite (brown coal) mine near the town. This environment helped preserve the wooden spears, which otherwise would have long ago rotted away. The spears are about 400 000 years old, making them the world's oldest human-made wooden artefacts, as well as the oldest weapons, ever found.

Three of them were probably manufactured as projectile weapons, because the weight and tapered point is at the front of the spear making it fly straight in flight, similar to the design of a modern javelin. The fourth spear is shorter, with points at both ends and is thought to be a thrusting spear or a throwing stick. They were found in combination with the remains of about 20 wild horses, whose bones contain numerous butchery marks, including one pelvis that still had a spear sticking out of it. This is considered proof that early humans were active hunters with specialised tool kits.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Additional text: Wikipedia

Photograph of one of the Schöningen spears when first found during the 1990s. It was initially proposed that these spears represented the earliest known simple projectile weapons found, since they were dated to 300 000 BP. This proposition places the timing of their emergence with the existence of Homo heidelbergensis.

(Note that the wooden spear has been deformed somewhat by the weight of sediments above it over hundreds of thousands of years. It would, presumably, have initially been straight, with any kinks in the original shaft being taken out by bending while passing it over a fire - Don )

Recently, however, a number of studies have shown that these spears were most probably not used as projectile weapons. In one such study, the size of the tip of the spear was found to be too large to be thrown. The study found that if they had been projected, they could not have been thrown far enough to offer a significant hunting advantage.

(I find this difficult to believe. The pilum was a javelin used by the Roman army. It was generally about 2 metres, well over six feet in length overall, about the same as the spear shown here, and weighed anywhere from 2 to 5 kilograms, 4½ to 11 pounds. The spear shown here would have been lighter than the Roman pilum, which had a heavy iron tip and shank attached to a wooden shaft, and which had a maximum range of approximately 33 metres (100 ft), although the effective accurate range was more like 15–20 m (50–70 ft). This is certainly a good enough range for hunting animals, just as it was for bringing down opposing soldiers for the Roman army - Don )

Photo and text: https://dansimcha.wordpress.com/2012/11/06/initial-schoningen-spear-theory-questioned/

Additional text: Wikipedia

Additional reference: Conard et al. (2015)

A more detailed page on the Schöningen Spears.

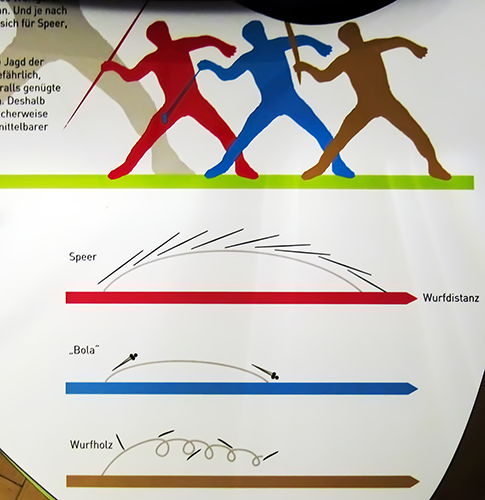

This diagram shows clearly the flight paths, and relative distances attained when thrown, for the spear, bola, and throwing stick.

Photo of Display: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Acheulean Hand Axe

Cordiform (heart shaped) Profile.

Palaeolithic, circa 500 000 BP

This is a classic quartzite Acheulean handaxe from North Africa, found in a dry watercourse, a small tributary of the Draa river, near Tan Tan,

at N 28.23233, W 10.59947.

Dimensions 220 mm x 115 mm x 60 mm.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2016

Source: Private collection

Dry wadi from which the handaxe above was retrieved.

It is a small tributary of the Draa river, near Tan Tan,

at N 28.23233, W 10.59947.

It is thought that an exceptional flood deposited all these stones here at once.

Photos: © Corry Zuurdeeg

Bifacial flint hand axes, 300 000 BP.

From France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Bifacial flint hand axes, 300 000 BP, from France. These are the same specimens as the two in the photo above.

Although developed more than one million years ago in Africa, the hand axe spread throughout Europe over time. The early handaxe industry of Western Europe is named after the site of Saint Acheul near Amiens, as Acheulian.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Acheulian hand axes, 300 000 BP, from la Micoque, France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Spear point, 300 000 BP - 250 000 BP, from the Belvédère loess and gravel quarry, near Maastricht, Netherlands.

In 1980 archaeologists discovered a Neanderthal site in the Belvédère loess and gravel quarry, near Maastricht. Twelve concentrations of flint and bone material were excavated. Some of the 'encampments', situated on the banks of the Meuse (Maas) River at that time, date from a warm period before the last ice age, over 250 000 years ago.

The densely wooded region overlooked a sluggish, widely meandering river. Deciduous forests surrounded the old river channels. Higher up, the land was more open. The sites were covered with sediment when the Meuse flooded its banks, preserving everything more or less intact. By refitting pieces of flint debris and tools, we can learn more about the activities of Neanderthals. We find that they often visited the banks briefly, to make or repair tools and search for flint. Some tools were taken elsewhere, while others were used in the direct vicinity.

The wooded, watery region of the Meuse (Maas) valley abounds in foods such as fruits, nuts and fish. As keen meat eaters, the Neanderthals hunted game. Animals like rhinoceros, forest elephant, bison, roe deer, and giant deer liked to graze and drink on the banks of the Meuse, making this an ideal hunting ground.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Lupemban-style flake used as a scraping tool by Homo heidelbergensis or early Homo sapiens.

From Kalambo Falls, Tanzania/Zambia border, around 300 000 BP to 200 000 BP.

Catalog: E3647

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

Backed knife, flint, site G, 300 000 BP - 250 000 BP, from the Belvédère loess and gravel quarry, near Maastricht, Netherlands.

Neanderthals were excellent hunters. Their weapons and technical prowess, and above all their communication, planning and intelligence put them at the top of the food chain. But how can flint provide the proof for this? Much can be learned by microscopically examining the traces of wear on flint and reproducing these in experiments.

Traces found on one knife resemble those made when slaughtering a thick-skinned animal or pachyderm. The knife in question was found among the remains of two young rhinoceroses.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Six quartzite handaxes from the Sahara, circa 200 000 BP.

Handaxes are a characteristic tool of the ancient palaeolithic. Typical are the round base and the opposite point. Handaxes were made without a handle, and were held and used in the fist.

On their surface, the pieces typically show the so-called 'desert lacquer', a patina which is formed by their time on the surface of the desert.

Catalog: Inv. No. 2008 / 835-840

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Flint handaxe, 200 000 BP - 150 000 BP.

( This is a quite sophisticated tool for the time. Certainly it is fairly thick, but it is much longer than it is wide, unusual for a handaxe, and it has been beautifully finished with careful and skilled retouching on the faces and edges, in the style of a much later era. - Don )

Rheindahlen, Stadt Mönchengladbach

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Broad quartzite handaxe, location unknown.

Old Palaeolithic

The piece is distinguished by its oval shape, compared with the more normal pointed shape. No doubt the piece has been extensively reworked after much use.

Its desert lacquer patination came from spending some time on the surface of the ground.

Catalog: Inv. No. C 735

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Quartzite handaxe from the old Palaeolithic of East Africa.

These were used for cutting, stabbing, drilling, scraping and striking. They were thus an optimal tool for cutting up animals after hunting. Because of the wide range of uses, the handaxe is also known as the 'Swiss Pocket Knife of Prehistory'.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Hand axes from North Africa.

200 000 BP.

These are of a coarse grained material, possibly quartzite.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Flint spear tips, circa 200 000 BP - 150 000 BP.

Rheindahlen, Stadt Mönchengladbach.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Additional text: http://www.georallye.uni-bonn.de/kartstein_bei_satzvey

Acheulian hand axe.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Aquitaine à Bordeaux

Levallois Point, in flint.

From Therdonne, France

Circa 178 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Handaxe, Soissons, France.

Circa 120 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

On loan from the Löbbecke Museum, Düsseldorf.

Handaxe, France.

Circa 120 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

On loan from the Löbbecke Museum, Düsseldorf.

Handaxe, France.

Circa 120 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

On loan from the Löbbecke Museum, Düsseldorf.

Legacies of the Neanderthals

These handaxes and flake tools are made to a large extent from chert coming from deposits in the area near Stuttgart.

Various stone tools from Heidenschmiede, Heidenheim, district Heidenheim, circa 120 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

(left) Point, radiolarite

(centre) Hand axe, Jurahornstein, Jurassic chert.

(right) Faustkeilblatt, flat or leaf hand axe, chert.

Circa 120 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Along the southwestern bulwark of the castle in Heidenheim, the rock face 35 metres above the valley floor forms a small overhang just large enough to create an 8 square metre abri, or rock shelter. Together with the open space in front of it, the cave has a usable area of some 30 square metres.

In spite of its small size, this so-called Heidenschmiede, or heathen's forge, rock shelter was a place our ancestors went to time and again. This may have been because of the splendid view across the wide, open valley of the Brenz River, which provided an excellent hunting ground.

Heidenheim is about 100 km to the east of Stuttgart.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015, 2018

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

The later flint tools of the Neanderthals were made of flakes struck from specially prepared cores. This Levallois technique takes its name from a site at Levallois in western France.

(left) Levallois flake from Vailly-sur-Aisne, western France, 100 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

(right) Levallois core and flake from Montières, western France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Closeups of the tools above:

(left) Levallois flake from Vailly-sur-Aisne, western France, 100 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

(right) Levallois flake from Montières, western France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

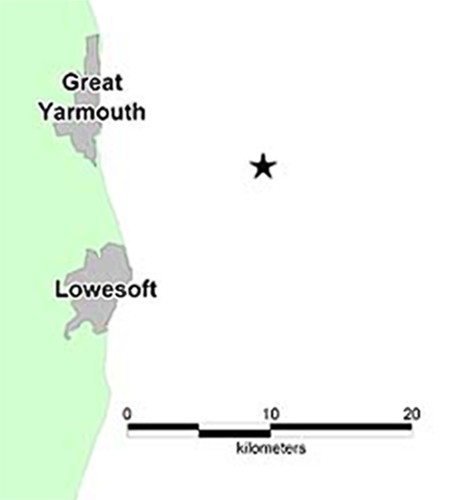

Four Neanderthal handaxes, recovered from the bed of the North Sea offshore from Yarmouth by dredging.

An amazing haul of 28 flint hand-axes, dated by archaeologists as around 100 000 years old, have been recovered off the coast of Norfolk.

The remarkable find was made by a Dutch amateur archaeologist, Jan Meulmeester, who sifted through gravel unearthed from a licensed marine aggregate dredging area 13km off Great Yarmouth and delivered to a wharf in southern Holland.

Reckoned to be the finest hand-axes that experts are certain come from English waters, the rare finds show that deep in the Ice Age, mammoth hunters roamed across land that is now submerged beneath the sea.

'These finds are massively important', said Ice Age expert Phil Harding of Wessex Archaeology and Channel 4’s Time Team. 'In the Ice Age the cold conditions meant that water was locked up in the ice caps. The sea level was lower then, so in some places what is now the seabed was dry land.'

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden, on loan from the Meulmeester Collection

Text: http://www.culture24.org.uk/history-and-heritage/archaeology/art55043

Flint handaxes from Vailly-sur-Aisne, western France, 100 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Eight flint points, the back and middle rows and the two left in the front row, perhaps for spears, Le Moustier. 100 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

Front row right: Flint point, perhaps for a spear, Pech de l'Azé.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Retouched flakes and scrapers, La Ferrassie, 100 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Hand axes from France.

90 000 - 36 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Bifacial flint hand axes, Middle Palaeolithic, circa 90 000 BP.

Le Moustier and Moulin-Truignon/Somme

(the first three of these are the same as in the handaxes immediately above, rotated 180°)

In the course of development handaxes became smaller and smaller.

In the Middle Palaeolithic - the time of the Neanderthals - flakes began to displace the old Paleolithic nuclear tools. The tools became more specific and versatile.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Flint (jasper) tool from Freiburg. Mousterian culture, circa 80 000 BP.

Small Mousterian ovate hand axe / scraper.

Note the large flake taken out for a thumb grip. There are many neanderthal tools (and even some upper palaeolithic tools) with this feature.

The blank was struck from a flint (jasper) core and bifacially worked in the handaxe tradition.

Worked on both sides, this piece still stands in the long tradition of early handaxes, but is characterised by careful restoration of a flat surface. It may have been used as both a scraper and a handaxe.

In the case of fairly small tools such as this, it is often difficult to determine if it is primarily a Breitschaber / Blattschaber (wide / blade scraper) or Faustkeil (hand axe).

It may have been used as a handaxe in the morning, and a scraper that afternoon. Not for nothing is the classic handaxe known as the 'Swiss Army Knife' of Palaeolithic tools. Many millions were made, and used for many purposes - cutting, scraping, smashing bones to obtain the marrow, or choppers for cutting up carcasses or cutting down small trees.

Similar tools are also known from other European sites and are referred to as the Mousterian culture after the French site of 'Le Moustier' (Dordogne / France). This culture was of Neanderthal origin.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008, 2015

Source: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Racloir, in jasper, from Fontmaure (Vellèches), France

Middle Palaeolithic.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Musée d'Archéologie nationale - Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Two small bifaces from Fontmaure (Vellèches), France

(left): Flint

(right): Jasper

Middle Palaeolithic.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Musée d'Archéologie mationale - Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Mousterian point from Fontmaure (Vellèches), France

Jasper.

Middle Palaeolithic.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Collections du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Micoquien quartzite hand axe from Bruchsal, district Karlsruhe, Middle Palaeolithic, circa 80 000 BP.

Despite its relatively young age, the tool belongs to the development series of the Palaeolithic hand axes. It belongs to the Neandertal stone industry described as the 'Micoquien' according to the reference to the site of La Micoque in France. Contrary to the often crude representation of the Neanderthals, their tools testify to enormous skill.

( note that the shape of this handaxe is not of the type generally ascribed to the Micoquien. I can only assume that it has been ascribed to the Micoquien industry because of its possible asymmetry between front and back faces, another characteristic of the (as originally described) Micoquien industry. It may also be placed in this industry because of being part of the wider culture known as Micoquian/Keilmessergruppen - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Catalog: lnv.-Nr. 2008/628

Source and text: Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe Germany

Scrapers and a point from La Micoque, 80 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neues Museum, Germany

Text: © Card at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DE)

Small hand axes or points from La Micoque, 80 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neues Museum, Germany

Text: © Card at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DE)

Levallois point and scrapers from La Micoque, 80 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neues Museum, Germany

Text: © Card at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DE)

Hand axes from La Micoque, 80 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

( note that in both these examples, the whole face has not been worked, and there are parts of the original cortex remaining - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Neues Museum, Germany

Text: © Card at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 DE)

Blade, in flint.

From Bettencourt-Saint-Eaux, France

Circa 75 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Collections du Musée national de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Levallois nucleus/core from the region of Bergerac.

This is superb quality flint, worked by a master craftsman.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Catalog: 2006.17.16.1

Source: Original, Musée d'Aquitaine à Bordeaux

Mousterian biface hand axe, made of flint. This is an important piece from the Department Vienne near Châtellerault (La Belle Indienne), as may be seen from the inscription on the axe.

Length 172 mm, width 126 mm, thickness 27 mm.

This handaxe is seen by many collectors as the non-plus-ultra for the Moustérien de tradition acheuléenne (MTA) bifaces.

Note that at the time of writing the catalog of the museum is in error regarding its origin, ascribing it to Fontmaure (Vienne). My thanks to Katzman of http://www.aggsbach.de/ for the heads up about this important discrepancy. See http://www.aggsbach.de/2016/10/the-ordinary-and-the-special-triangular-handaxes-bifaces/

Katzman writes (p.c.) that about 2006 an American collector bought a similar piece at a French auction house for $14 000 USD.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Additional text and access to Bordes (1979): Katzman of http://www.aggsbach.de/

Catalog: 60.1563.1

Source: Original, Musée d'Aquitaine à Bordeaux

These are the drawings of the piece above by Bordes from his text Typologie du Paleolithique ancien et moyen, 1979.

Photo: Bordes (1979)

Neanderthals were master stone knappers. They possessed a sense of aesthetics and an intuition for the right material, as may be seen from their handaxes.

In Heidenschmiede there were numerous stone tools made from fresh water quartzite. This is a material very similar to flint, and outcrops only a few kilometres from the site.

Four views of a handaxe, freshwater quartzite, Heidenschmiede, Heidenheim, district Heidenheim.

Because of its asymmetry, this handaxe might well be ascribed to the Micoquien culture.

Circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Length 148 mm, width 71 mm.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

Small handaxe, circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

Jurahornstein, Jurassic chert.

Heidenschmiede, Heidenheim, Kreis Heidenheim.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

Rich Booty

Around 1600 artefacts from Neanderthals have been recovered in Wittlingen so far. It is the only large open-air station in the Swabian Alb from this era. Tools were mainly made of flakes. All that remained at the site was production waste, which could not be used any further.

From previous observations at other locations, and from the study of original flint deposits nearby, there is evidence that completed tools were carried to the site, which were then used here in Wittlingen until they became useless. The original deposits of the material used for these artefacts lie 50 to 100 km from Wittlingen.

Two leaf points and a blade, circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

Artefacts struck from Wittlinger chert, Bad Urach, Wittlingen, Kreis Reutlingen, about 30 km south east of Stuttgart.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015, 2018

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

On loan from the Archäologischen Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg

Points, circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

Artefacts struck from Wittlinger chert, Bad Urach, Wittlingen, Kreis Reutlingen, about 30 km south east of Stuttgart.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

On loan from the Archäologischen Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg

Wide scraper in siliceous slate, from Bad Urach, Wittlingen, Kreis Reutlingen.

Circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

On loan from the Archäologischen Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg

Scraper, Muschelkalkhornstein, Middle Triassic chert, from Bad Urach, Wittlingen, Kreis Reutlingen.

Circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

On loan from the Archäologischen Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg

Scraper, red radiolarian chert, from Bad Urach, Wittlingen, Kreis Reutlingen.

Circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

On loan from the Archäologischen Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg

Scraper, green radiolarian chert, from Bad Urach, Wittlingen, Kreis Reutlingen.

Circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

On loan from the Archäologischen Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg

Residual core of Wittlinger Jurassic chert, Bad Urach, Wittlingen, circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

On loan from the Archäologischen Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg

Flint racloirs, or side scrapers, from Abri Reignoux (Abilly), France.

Original, circa 70 000 BP - 50 000 BP.

( note that both these scrapers have had a flake taken out on the right, presumably for the thumb to more easily grasp the tool. This feature is not uncommon in Neanderthal tools designed to be held in the hand - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Collections des Amis du musée de Grand-Pressigny, Musée de la Préhistoire du Grand-Pressigny

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

Flint handaxe, circa 50 000 BP.

Dülken-Hausen, Kreis Viersen.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Flint handaxes, circa 50 000 BP.

Erkrath, Kreis Mettman.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Modern reconstruction of a leaf-shaped scraper attached with birch pitch to a wooden handle.

As used in the late Middle Palaeolithic, i.e. circa 50 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Leaf shaped scraper.

Flint, circa 50 000 BP.

Weeze, Kreis Kleve.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Flint handaxe, circa 50 000 BP.

Elmpt, Gemeinde Niederkrüchten, Kreis Viersen.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Biface, in flint, from Saint-Amand-les-Eaux, France, circa 49 200 BP.

( This is a superb piece of work, worthy of pride of place in any art gallery in the world, yet such masterpieces were produced in their millions. Sometimes when I am putting up these photographs, I am struck by the love of symmetry and beauty in all humans.

We make things better and more perfect than they need to be, just because of the way we are. We take far more time and effort and skill to create useful things than they logically require. We take pride in our work, and make things as well as we are capable of, whether the object requires such accuracy and care or not.

A simple chopper, made in a minute or two from a pebble in a stream bed, would have performed most of the tasks demanded of this beautiful tool.

The creator of this handaxe died nearly fifty thousand years ago, but this artefact they left behind gives us a small though imperfect window through which to see the things that were important to them in their daily lives, and their pride in good workmanship for its own sake - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Musée de l'Homme, Paris

The invention of the bow and arrow

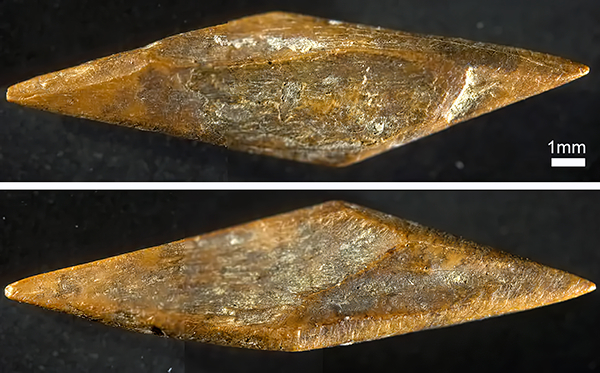

Michelle Langley, Senior Research Fellow, Griffith University, Oshan Wedage Researcher, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, and Patrick Roberts, Research Group Leader, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History have published evidence for the use of bow and arrow technology from 48 000 BP in the forests of Sri Lanka.

Reference: Langley et. al. (2020)

One of the small bone points discovered at Fa-Hien Lena, in Sri Lanka, circa 48 000 BP

Photo: © M. C. Langley

Source and text: https://theconversation.com/48-000-year-old-arrowheads-reveal-early-human-innovation-in-the-sri-lankan-rainforest-139989

( It would seem to me that the bow and arrow is a hunting technique dependent on the existence of forests. It was apparently not invented in Europe until conditions became warm enough for extensive forests, and the earliest evidence we have from there is circa 18 000 BP.

Before that time, the spear thrower, or atlatl, was an invention which greatly increased the distance that a spear could be thrown, but it performs best in open country, where the hunter has room to throw the spear. It is far less useful in forests, which is where the bow and arrow comes into its own. The hunter can more easily get closer to the prey without being seen, and the bow and arrow is very accurate at those shorter distances.

However evidence has now been found for the use of the bow and arrow in Sri Lankan rainforests about 48 000 years ago. - Don )

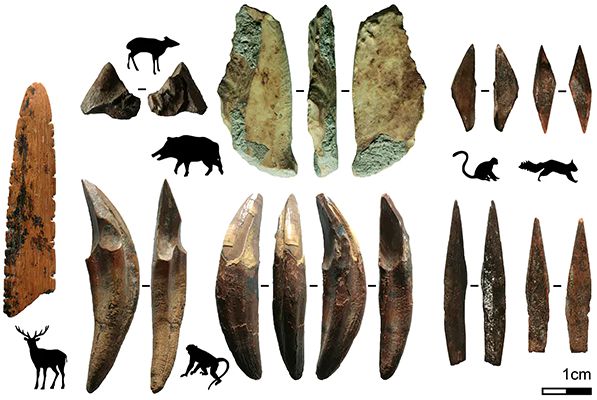

Bone technology of Fa-Hien Lena. Tools made from bone and teeth of monkeys and smaller mammals recovered from Fa-Hien Lena, Sri Lanka. This technology included small bone arrow points (bottom right), and skin or plant-working tools.

Photo: © M. C. Langley

Source and text: https://theconversation.com/48-000-year-old-arrowheads-reveal-early-human-innovation-in-the-sri-lankan-rainforest-139989

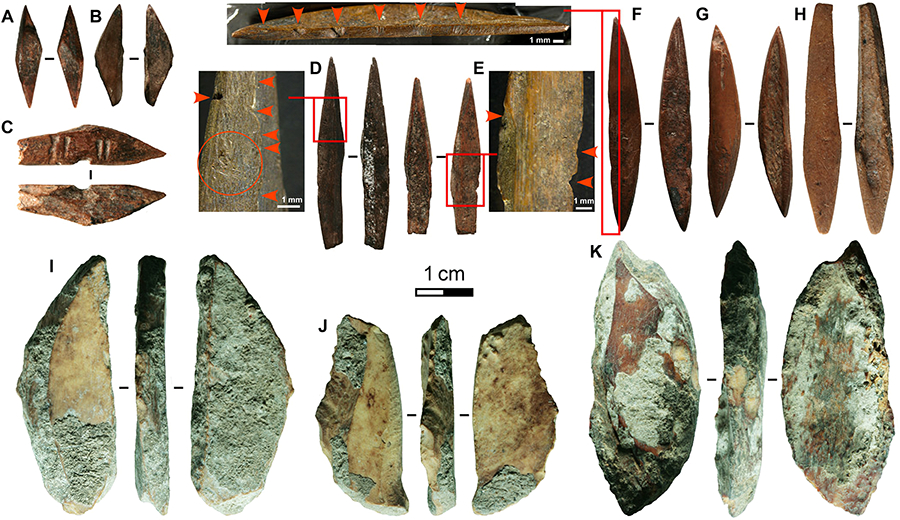

Pointed bone technologies of Fa-Hien Lena.

Bone projectile points (A to H) and scrapers (I to K) from Fa-Hien Lena. (A and B) Geometric bipoints, with (B) coming from phase D context 146; (C and F) hilted bipoint, red arrows indicate cut notches; (D and E) hilted unipoints, red arrows and red circle indicate wear indicating fixed hafting; (G and H) symmetrical bipoints.

Photo: © M. C. Langley

Source and text: Langley et. al. (2020)

Blattspitz, Leaf Point, France.

38 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

On loan from the Löbbecke Museum, Düsseldorf.

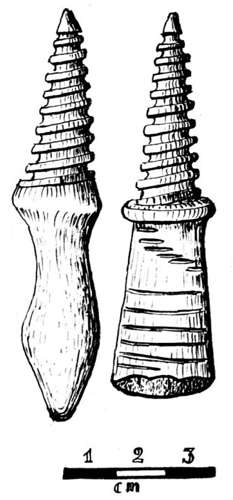

Screw Thread Corks

These are the most delightful tools I have ever seen. They are from the Perigordian IV, which is 30 000 BP to 28 000 BP.

They are called 'goat skin corks' which have a hand cut screw thread!

I was staggered when I saw them, I was looking for something else, and came across them by chance. You don't expect to find a screw thread in the Palaeolithic!

It would be a great way to get a watertight seal for a wineskin or waterskin. One should never underestimate the ingenuity of the human race. It was a palaeolithic Einstein who came up with that one - and a tour de force for the artisan who actually made it! Think of the special tool that would have been made in order to get it perfect….. It looks like a teamwork job to me, somebody to think of it, a group of people to create the tools necessary, and decide on the materials - wood? bone? ivory? and a long process in order to make it, ironing out the inevitable problems as they occurred.

It also indicates a large measure of affluence. People who live hand to mouth don't come up with a whimsical invention like this, and don't have the time, resources or energy to see the project through.

They are from two different sites, but the same time period. My bet is that both were made at one site, and traded to another. No two people come up with an intellectual leap like that independently, at the same time. It had to have been made by the same artisan or group of artisans, for sure. What is interesting, however, is that this was invented, but never became popular except in one general area at one time, about 30 000 years ago. I am reminded of the invention of ceramics at Dolni Vestonice, which flourished for a short time, then disappeared for tens of thousands of years.

The one on the left is from Roc de Combe-Capelle, and on the right from Fourneau du Diable. They are both in the Dordogne area, about 90 kilometres apart.

Notice that they are both right hand threads, showing that right handedness in humans has been around for a long time - though we knew that anyway because of the differences in arms on the right and the left of skeletons. Mungo Man had a wonky right elbow, either from using a spear thrower or a spear. It is given as evidence of a spear thrower 40 000 years ago, but it could just as well have been from throwing a spear.

The material of both is ivory. Hard to work, but it would be very durable. You are subjecting that thing to a lot of stress. Brass would have been better still……

Note that what follows is my version of how to use the stopper, not something that I know works, I've never actually made or used the complete set of equipment needed. But this thought experiment would be a good start, I reckon.

If I were going to make the whole shebang, I'd start with the complete hide of an animal such as an ibex. Pigs are good, I've drunk wine in spain (very ordinary wine I might add) that was stored in a complete pig's hide. I don't know how they did that, I assume they decided what they were going to do with the hide before they started, and made the smallest incisions possible to get out the squishy bits. The one I saw had only stumps of skin at the legs and neck, tied down firmly as you would expect. The advantage of a larger animal is that, of course, you can store a lot more liquid all at once.

OK, so imagine we've got a skin that is waterproof, an ibex skin say, with an outlet, let's say the front right leg of an ibex. This is a relatively large orifice, but it has a lot of loose skin flapping around. The other openings are folded over and tied down. One of these can be the filling hole, when ready for use as a water container you could untie it, fill the skin, then retie it.

You then take the femur (thighbone) of an aurochs or ibex, or rabbit, whatever you like, they are hollow because they are the repository of marrow, and are close to cylindrical.

Or a human thighbone if you aren't squeamish. Maybe that of your favourite aunt or your worst enemy.

Wood could be used, but it would probably split open very quickly, or immediately, probably, because of the stresses. That stopper is a wedge which would only be resisted by something very tough, like a femur. There are firewood splitters that actually work on the conical thread principle.

If available, I'd use an ibex femur, they average about 18 mm (female) to 22 mm (male) in diameter (Fernandez et al., 2006) at the smallest section of the diaphysis, the shaft of the femur. The lower, thickest part of those two screw threads is about 10 mm, so an ibex femur would be ideal.

All you'd do is circumscribe the bone at two convenient places near the middle where you are going to snap the rest of the bone off, either end.

Then circumscribe a few shallow (at least two) grooves in between the two deeper grooves. This provides a good method for securing the bone in the next step. Snap off the two ends at the two deeper grooves.

Wrap the loose skin of the wineskin at the orifice left unsealed around the bone cylinder, and make the junction waterproof by tying tightly with cords at the two (or more) grooves. This will form the pouring spout of the wineskin.

From a smaller animal, carefully remove the skin of a suitable part of the femur, but in a cylindrical state, not cut. Though I suspect you'd get away with just a rectangular piece of hide. I don't think it is critical that you have a cylindrical unbroken piece of hide, so long as what you had was soft.

Now you can start.

You have selected the cylindrical bit of skin so that it is about the same diameter, maybe a bit more, as the hole left by the marrow, which you have scooped out. Put this skin inside the thighbone.

Fill the 'wineskin' with water, (as above, you could instead use one of the other larger orifices in the hide, which you then fold over and tie down) and screw in the stopper.

The skin inside, between the stopper and the bone, forms a gasket so that water doesn't escape down the thread. The inside of the bone is compressible to a certain extent, and will soon conform to the thread of your stopper.

You need the screw thread to be conical because it allows you to use the same ivory stopper in a number of different sized femurs, and in any case, the conical shape means you can get the stopper really tight. The further in you screw the stopper, the tighter it presses against the inside of the femur. As the inside of the femur compresses with time ( it will! ) you just screw the stopper a little bit tighter. You might notice that the stopper goes a little further in every month or so for a while until the inside of the femur, and the leather cylinder 'washer' is compressed as far as it is going to go.

The threaded parts of the stoppers are about 35 - 40 mm (1.5 inches) long, the handle on the right is 40 mm (1.5 inches) long, the one on the left is 50 mm (2 inches) long. They are only small, about 90 mm (3.5 inches) long all up.

Photo: Lwoff (1962) after Peyrony

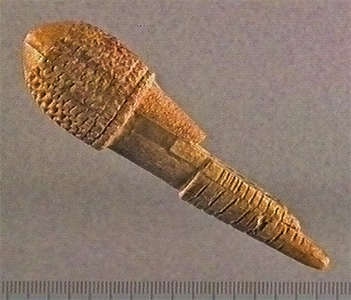

Ivory stopper for a leather water bottle, from Fourneau du Diable.

This is the original of the stopper on the right above. If you compare the drawing and the photo, it would appear that Peyrony (it is his original drawing, but was redrawn by Lwoff (1962)) has 'gilded the lily' more than a little with regard to the perfection of the screw thread. The thread is not nearly so deep, nor as perfectly helical, as he would have us believe. That's not like Peyrony. I regard him as the most important figure, apart from Breuil, of early French archaeology. I'd love to get a better photo from several angles of the original stopper.

Photo: Delluc & Delluc (1982)

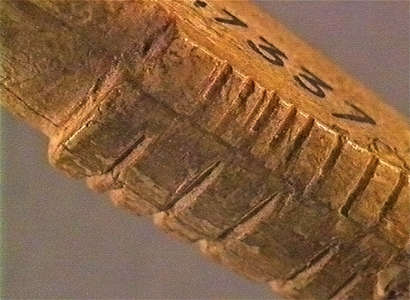

Ivory stopper for a leather water bottle, from Laugerie Haute Est

This version has a rounded helix.

(left) Photo and origin: Bordes (1959), Bordes (1978)

(right) Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

This is an ivory waterbag stopper from Brassempouy.

(this appears to be a museum quality facsimile - Don )

Photo: http://paleobox.forumactif.com/t2049p40-sortie-paleobox-le-29-septembre-au-man

Source: Display at Musée d'Archéologie nationale, Saint-Germain-en-Laye

This is the ivory waterbag stopper from Brassempouy.

(this appears to be the original - Don )

Photo: © Saint-Germain-en-Laye, musée des antiquités nationales, © Direction des musées de France, 2002

Source: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/

Aurignacian, deeply carved. The upper part of the object is smooth and rounded. It is followed by a cylindrical band fully decorated with rows of serpentine patterns.

The centre of the object is a wide band forming a constriction. The lower tapering part is decorated several rows of transverse incisions.

Photo: © Saint-Germain-en-Laye, musée des antiquités nationales, © Direction des musées de France, 2002

Source: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/

Length 91 mm, maximum diameter 25 mm

Photo: © Saint-Germain-en-Laye, musée des antiquités nationales, © Direction des musées de France, 2002

Source: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/

The concept of the helix, used in some of the water skin stoppers, was familiar to the stone age inhabitants through sea shells.

These non-pierced interior casts of fossil Turritella, L. max.: 2.60 cm Ø max. 1.05 cm, a total of 180 pieces, were found at Grottes de Goyet, Belgium, in Magdalenien layers, ca 12 000 BP.

They are believed to have been sewn onto a bib of leather to be hung on the chest.

Photo and text adapted from: Cattelain et al. (2012)

Tools from le Ruth, Aurignacian, 30 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

(left) Stielspitze, Shouldered Point, Laugerie-Haute, France.

(right) Stielspitze, Shouldered Point, Vézère valley, France.

22 000 BP - 18 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

(left) On loan from the Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Universität Tübingen

(right) On loan from the Löbbecke Museum, Düsseldorf.

Tools from Solutré, Solutrean, 18 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Limestone cliffs near Solutré, at the foot of which is the celebrated site of Cro-du-Charnier

Photo: Yelkrokoyade (2009)

Burins, Les Eyzies, France.

18 000 BP - 12 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

On loan from the Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Universität Tübingen

Scraper - burin, St.-Léon-sur-Vézère, France.

18 000 BP - 12 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

On loan from the Löbbecke Museum, Düsseldorf.

Projectile points of reindeer antler, originals.

( note that the bevels have had grooves cut in them in order to enhance adhesion when the points are glued with birch-bark glue to the spears - Don )

18 000 BP - 12 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

Mallet made of reindeer antler, 15 800 BP

Andernach-Martinsberg, district of Mayen, Koblenz, from the excavations of Hermann Schaaffhausen 1883.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Lender: Directorate General for Cultural Heritage Rhineland-Palatinate, Generaldirektion Kulturelles Erbe Rheinland-Pfalz

Quartzite burins, 15 800 BP

Andernach-Martinsberg, district of Mayen-Koblenz, from the excavations of Hermann Schaaffhausen 1883.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany

Quartzite scrapers, 15 800 BP

Andernach-Martinsberg, district of Mayen-Koblenz, from the excavations of Hermann Schaaffhausen 1883.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, Germany