Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

The Ishtar Gate at Babylon

The Ishtar Gate at Babylon

Ancient Mesopotamia

Ancient Mesopotamia

The Neo-Assyrian

Artefacts from the Neo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was a powerful state that existed in the ancient Near East from 911 BC to 609 BC. It was the largest empire in the world at the time and covered much of modern-day Iraq, Syria, and parts of Iran, Turkey, and Egypt. The Neo-Assyrians were known for their military might, efficient administration, and innovative use of technology, including the development of siege warfare and the use of iron weapons. They also had a well-organised system of government, with a king who had absolute power and a bureaucracy that helped him govern.

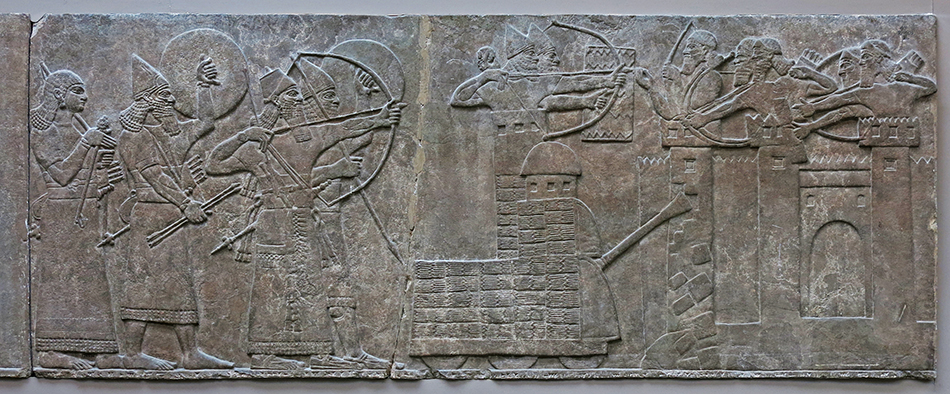

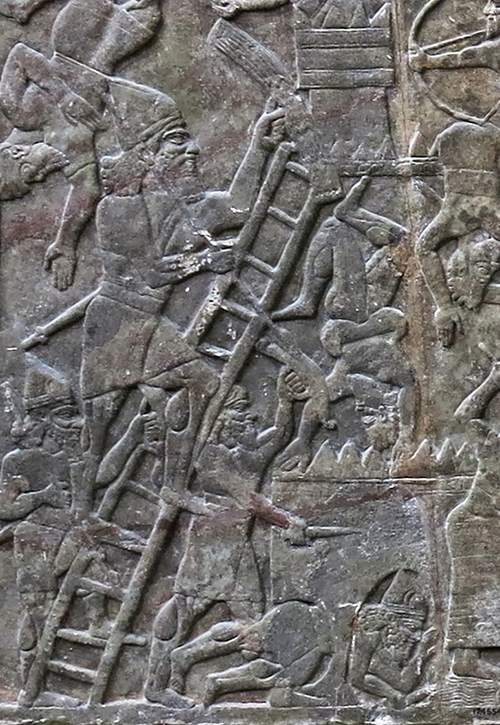

One of the most notable achievements of the Neo-Assyrians was their expansion of the empire through military conquest. They employed a standing army, which was one of the largest and most well-trained in the ancient world. The army was divided into specialised units, such as archers, infantry, and charioteers, and was equipped with advanced weapons and tactics. The Neo-Assyrians also developed a reputation for their brutal treatment of conquered peoples, often employing mass deportations and massacres to ensure obedience.

Despite their military might, the Neo-Assyrians were also known for their cultural achievements, particularly in the fields of art, literature, and science. They were great patrons of the arts and architecture, and built impressive structures such as the palace of King Sargon II at Dur-Sharrukin. They also produced great works of literature, including the epic of Gilgamesh, and made significant advances in science and medicine, with scholars producing important works on astronomy, mathematics, and the human body.

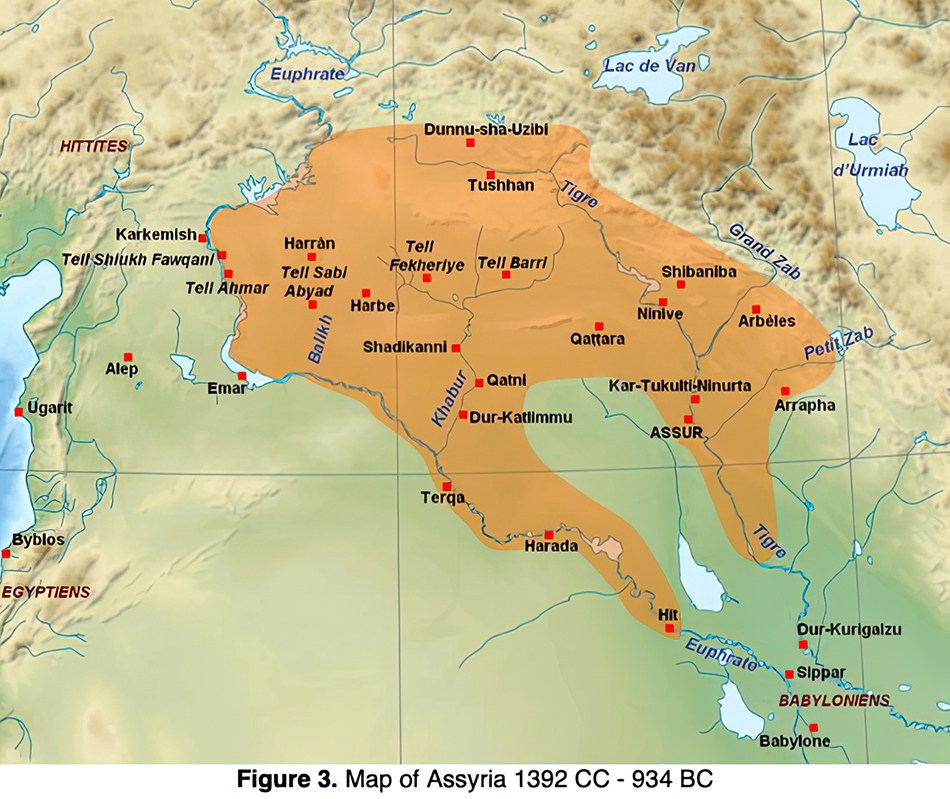

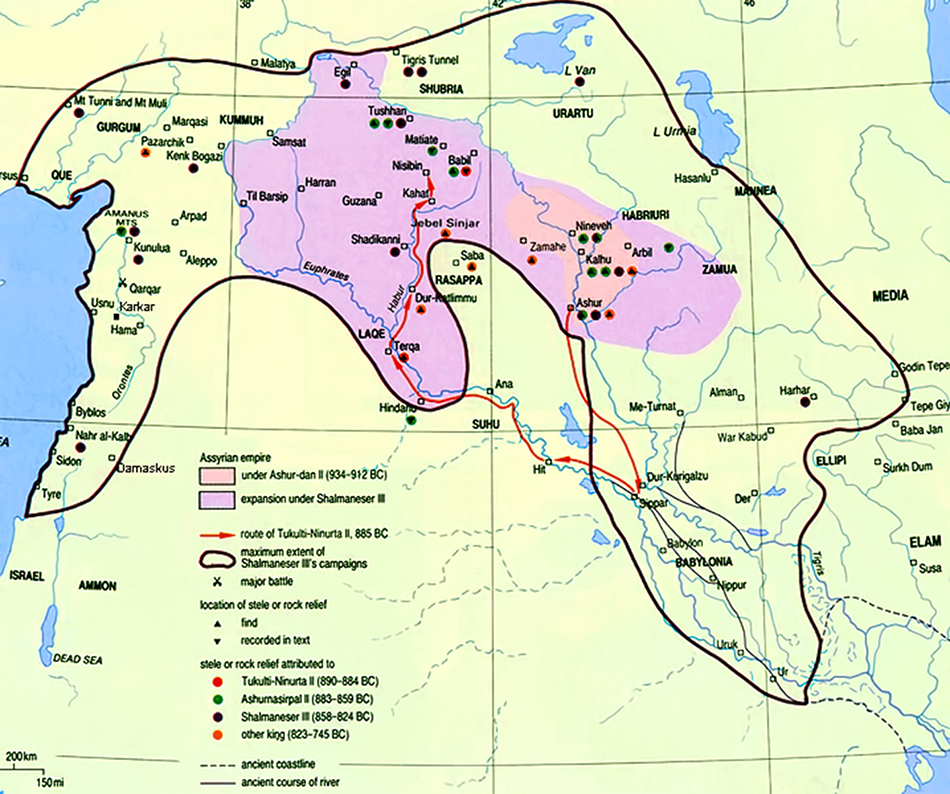

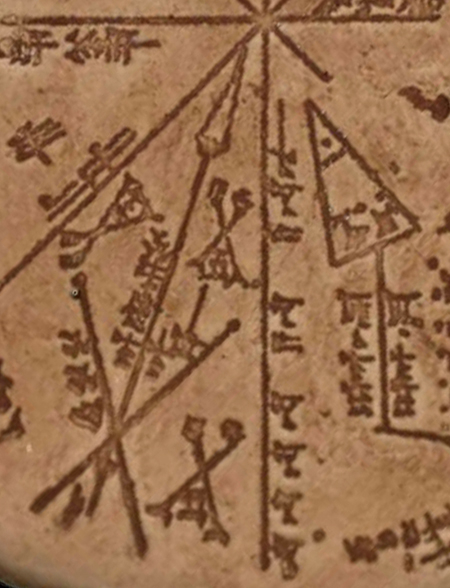

Map of the area of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Vorderasiatisches Museum, Ausführung: Christoph Forster, datalina

Source: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Pergamonmuseum

| Kings of Neo-Assyria | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Clickable Image |

Years | Dates | Comments |

| Ashur-dan II |  |

23 | 934 BC - 912 BC | Ashur-Dan II, son of Tiglath Pileser II, was the earliest king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He was best known for recapturing previously held Assyrian territory and restoring Assyria to its natural borders, from Tur Abdin (southeast Turkey) to the foothills beyond Arbel (Iraq). The reclaimed territory through his conquest was fortified with horses, ploughs, and grain stores. His military and economic expansions benefited four subsequent generations of kings that replicated his model. Ashur-Dan was the first king to conduct regular military campaigns in over a century. His military campaigns primarily focused on northern territories along mountainous terrain that made controlling it problematic. These areas were vital because they lay close to the Assyrian heartland and thus were vulnerable to enemy attacks. |

| Adad-nirari II |  |

21 | 911 BC - 891 BC | Adad-nirari firmly subjugated the areas previously under only nominal Assyrian vassalage, conquering and deporting troublesome Arameans. After subduing Neo-Hittite and Hurrian populations in the north, Adad-nirari II then twice attacked and defeated Shamash-mudammiq of Babylonia. He also campaigned to the west, subjugating the Aramean cities of Kadmuh and Nisibin. Along with vast amounts of treasure collected, he also secured the Kabur river region. His reign was a period of returning prosperity to the Middle East region following expansion of Phoenician and Aramaean trade routes, linking Anatolia, Egypt under the Libyan 22nd Dynasty, Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean. |

| Tukulti-Ninurta II |  |

7 | 890 BC - 884 BC | Tukulti-Ninurta consolidated the gains made by his father over the Neo-Hittites, Babylonians and Arameans, and successfully campaigned in the Zagros Mountains of Iran, subjugating the newly arrived Iranian peoples of the area, the Persians and Medes, during his brief reign. Tukulti-Ninurta II was victorious over Ammi-Ba'al, the king of Bit-Zamani, and then entered into a treaty with him, as a result of which Bit-Zamani became an ally, and in fact a vassal of Assyria. Tukulti-Ninurta II developed both Nineveh and Assur, in which he improved the city walls, built palaces and temples and decorated the gardens with scenes of his military achievements. |

| Ashurnasirpal II |  |

25 | 883 BC - 859 BC | During his reign he embarked on a vast program of expansion, first conquering the peoples to the north in Asia Minor as far as Nairi and exacting tribute from Phrygia, then invading Aram (modern Syria), conquering the Aramaeans and Neo-Hittites between the Khabur and the Euphrates Rivers. His harshness prompted a revolt that he crushed decisively in a pitched, two-day battle. The palaces, temples and other buildings raised by him bear witness to a considerable development of wealth and art. He was renowned for his brutality, using enslaved captives to build a new Assyrian capital at Kalhu (Nimrud) in Mesopotamia where he built many impressive monuments. He was also a shrewd administrator, who realised that he could gain greater control over his empire by installing Assyrian governors, rather than depending on local client rulers paying tribute. |

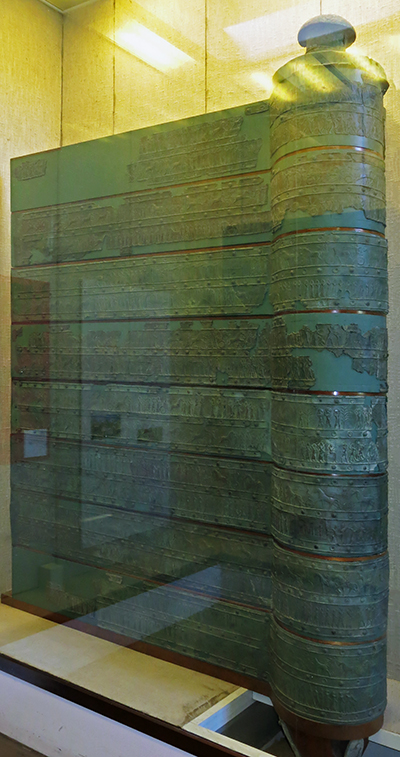

| Shalmaneser III |  |

35 | 858 BC - 824 BC | Shalmaneser III expanded the Assyrian Empire to include parts of modern-day Turkey, Iran, and Syria. He was known for his military campaigns, which he recorded on the Black Obelisk, a monument that lists the kings he defeated and tribute he received. One of Shalmaneser's most significant military campaigns was against the state of Urartu, located in modern-day Armenia. He attacked Urartu several times, almost every year of his reign, and eventually defeated the Urartian king Sarduri II in 843 BC. Shalmaneser also campaigned against the Aramaean states, including Damascus and Israel. He besieged Damascus twice but was unable to capture it. However, his campaigns weakened the Aramaean states and allowed Assyria to gain control over them. Shalmaneser was also known for his building projects, including the construction of the Central Palace at Nimrud. The palace was decorated with reliefs depicting scenes from Shalmaneser's military campaigns and showed his power and authority as the king of Assyria. He also built several temples in his honour, including the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu. |

| Shamshi-Adad V |  |

13 | 823 BC - 811 BC | The first years of Shamshi-Adad's reign saw a serious struggle for the succession of the aged Shalmaneser. The revolt was led by Shamshi-Adad's brother Assur-danin-pal, and had broken out already by 826 BC. The rebellious brother, according to Shamshi-Adad's own inscriptions, succeeded in bringing to his side 27 important cities, including Nineveh. The rebellion lasted until 820 BC, weakening the Assyrian empire and its ruler. Later in his reign, Shamshi-Adad campaigned against Southern Mesopotamia, and signed a treaty with the Babylonian king Marduk-zakir-shumi I. In 814 BC, he won the Battle of Dur-Papsukkal against the Babylonian king Marduk-balassu-iqbi, and a few Aramean tribes settled in Babylonia. The extent of Shamshi-Adad's victory was such that he obtained the submission of the Babylonian king and, after obtaining booty from several Babylonian cities, he returned to Assyria with palace treasures and sacred statues of gods. |

| Adad-nirari II |  |

28 | 810 BC - 783 BC | Adad-nirari's youth at the time of his ascension to the throne, and the struggles his father had faced early in his reign, caused a serious weakening of Assyrian rulership over their indigenous Mesopotamia, and made way for the ambitions of officers, governors, and local rulers. He led several military campaigns with the purpose of regaining the strength Assyria enjoyed in the times of his grandfather Shalmaneser III. He was the builder of the temple of Nabu at Nineveh. Among his actions was a siege of Damascus in the time of Ben-Hadad III in 796 BC, which led to the eclipse of the Aramaean Kingdom of Damascus and allowed the recovery of Israel under Jehoash (who paid the Assyrian king tribute at this time) and Jeroboam II. Despite Adad-nirari's vigour, Assyria entered a several decades long period of weakness following his death. |

| Shalmaneser IV |  |

10 | 782 BC - 773 BC | The accession of Shalmaneser IV marks the beginning of an obscure period in Assyrian history, from which little information survives. This period also extends throughout the reigns of his two immediate successors, his brothers Ashur-dan III and Ashur-nirari V. By the end of Adad-nirari III's reign, the Neo-Assyrian Empire was declining. In particular, the power of the king himself was being threatened due to the emergence of extraordinarily powerful officials, whom while they accepted the authority of the Assyrian monarch in practice acted with supreme authority themselves and began to issue their own inscriptions, similar to those of the kings. This arrangement continued during the reign of Shalmaneser and his immediate successors, a time from which inscriptions from such officials are more common than inscriptions by the kings themselves. At the same time, the enemies of Assyria grew stronger and more threatening. This period of Assyrian decline coincided with the peak of the northern Kingdom of Urartu. |

| Ashur-dan III |  |

18 | 772 BC - 755 BC | Ashur-dan ruled during a period of Assyrian decline from which few sources survive. As such, his reign, other than the broad political developments, is poorly known. At this time, the Assyrian officials were becoming increasingly powerful relative to the king and at the same time, Assyria's enemies were growing more dangerous. Ashur-dan's reign was a particularly difficult one as he was faced with two outbreaks of plague and five of his eighteen years as king were devoted to putting down revolts. |

| Ashur-nirari V |  |

10 | 754 BC - 745 BC | Like his predecessor, Ashur-nirari ruled during a period of Assyrian decline from which few sources survive. An unusually small share of Ashur-nirari's reign was devoted to campaigns against foreign enemies, perhaps suggesting domestic political instability within Assyria. In 746 or 745 BC, there are records of a revolt in Nimrud, the Assyrian capital. |

| Tiglath-pileser III |

|

18 | 744 BC - 727 BC | Tiglath-pileser was one of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings. He ended a period of Assyrian stagnation, introduced numerous political and military reforms and more than doubled the lands under Assyrian control. Because of the massive expansion and centralisation of Assyrian territory and establishment of a standing army, some researchers consider Tiglath-Pileser's reign to mark the true transition of Assyria into an empire. The reforms and methods of control introduced under Tiglath-Pileser laid the groundwork for policies enacted not only by later Assyrian kings but also by later empires for millennia after his death. Tiglath-Pileser early on increased royal power and authority through curbing the influence of prominent officials and generals. After securing some minor victories in 744 and 743, he defeated the Urartian king Sarduri II in battle near Arpad in 743. After defeating Sarduri, Tiglath-Pileser turned his attention to the Levant. Over the course of several years, Tiglath-Pileser conquered most of the Levant, defeating and then either annexing or subjugating previously influential kingdoms, notably ending the kingdom of Aram-Damascus. Tiglath-Pileser's activities in the Levant were recorded in the Hebrew Bible. After a few years of conflict, Tiglath-Pileser conquered Babylonia in 729, becoming the first king to rule as both king of Assyria and king of Babylon. |

| Shalmaneser V |

|

5 | 726 BC - 722 BC | Shalmaneser campaigned extensively in the lands west of the Assyrian heartland, warring not only against the Israelites, but also against the Phoenician city-states and against kingdoms in Anatolia. Though he successfully annexed some lands to the Assyrian Empire, his campaigns resulted in long and drawn-out sieges lasting several years, some being unresolved at the end of his reign. The circumstances of his deposition and death are not clear, though they were likely violent, and it is unlikely that Sargon II was his legitimate heir. It is possible that Sargon II was entirely unrelated, which would make Shalmaneser V the final king of the Adaside dynasty, which had ruled Assyria for almost a thousand years. |

| Sargon II |

|

17 | 721 BC - 705 BC | Modelling his reign on the legends of the ancient rulers Sargon of Akkad, from whom Sargon II likely took his regnal name, and Gilgamesh, Sargon aspired to conquer the known world, initiate a golden age and a new world order, and be remembered and revered by future generations. Over the course of his seventeen-year reign, Sargon substantially expanded Assyrian territory and enacted important political and military reforms. An accomplished warrior-king and military strategist, Sargon personally led his troops into battle. By the end of his reign, all of his major enemies and rivals had been either defeated or pacified. Among Sargon's greatest accomplishments were the stabilisation of Assyrian control over the Levant, the weakening of the northern kingdom of Urartu, and the reconquest of Babylonia. From 717 to 707, Sargon constructed a new Assyrian capital named after himself, Dur-Sharrukin ('Fort Sargon'), which he made his official residence in 706. |

| Sennacherib |

|

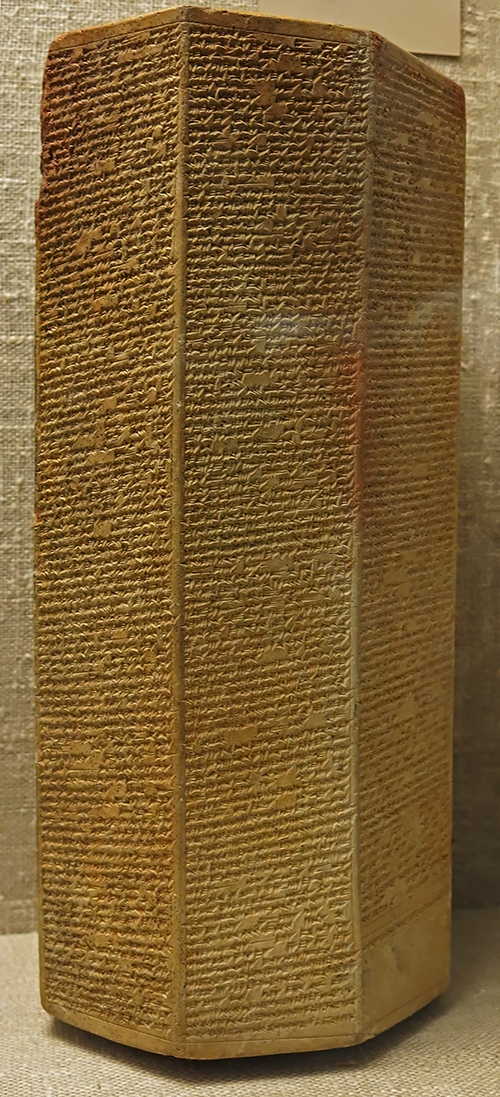

24 | 704 BC - 681 BC | The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous Assyrian kings for the role he plays in the Hebrew Bible, which describes his campaign in the Levant. (II Kings, II Chronicles, and Isaiah). Although Sennacherib was one of the most powerful and wide-ranging Assyrian kings, he faced considerable difficulty in controlling Babylonia, which formed the southern portion of his empire. Because Babylon, had been the target of most of his military campaigns and had caused the death of his son, Sennacherib destroyed the city in 689 BC. Sennacherib transferred the capital of Assyria to Nineveh, where he had spent most of his time as crown prince. To transform Nineveh into a capital worthy of his empire, he launched one of the most ambitious building projects in ancient history. He expanded the size of the city and constructed great city walls, numerous temples and a royal garden. His most famous work in the city is the Southwest Palace, which Sennacherib named his 'Palace without Rival'. In 681 BC, he was murdered by two of his sons who hoped to seize the throne, but another son, Esarhaddon raised an army and seized Nineveh, installing himself as king as intended by Sennacherib. |

| Esarhaddon |

|

12 | 680 BC - 669 BC | Esarhaddon is most famous for his conquest of Egypt in 671 BC, which made his empire the largest the world had ever seen, and for his reconstruction of Babylon, which had been destroyed by his father. After a very difficult ascension to the throne, Esarhaddon was plagued by paranoia and mistrust for his officials, governors and male family members until the end of his reign. As a result of this paranoia, most of the palaces used by Esarhaddon were high-security fortifications located outside of the major population centres of the cities. Also perhaps resulting from his mistrust for his male relatives, Esarhaddon's female relatives, such as his mother Naqiʾa and his daughter Serua-eterat, were allowed to wield considerably more influence and political power during his reign than women had been allowed in any previous period of Assyrian history. Despite a relatively short and difficult reign, and being plagued by paranoia, depression and constant illness, Esarhaddon remains recognised as one of the greatest and most successful Assyrian kings. He quickly defeated his brothers in 680, completed ambitious and large-scale building projects in both Assyria and Babylonia, successfully campaigned in Media, the Arabian Peninsula, Anatolia, the Caucasus, and the Levant, defeated and conquered Lower Egypt, and ensured a peaceful transition of power to his Ashurbanipal after his death. |

| Ashurbanipal |

|

38 | 668 BC - 631 BC | Ashurbanipal is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Inheriting the throne as the favoured heir of his father Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal's 38-year reign was among the longest of any Assyrian king. Though sometimes regarded as the apogee of ancient Assyria, his reign also marked the last time Assyrian armies waged war throughout the ancient Near East and the beginning of the end of Assyrian dominion over the region. Much of the early years of Ashurbanipal's reign was spent fighting rebellions in Egypt, which had been conquered by his father. Much of Ashurbanipal's late reign is poorly known. Ashurbanipal is chiefly remembered today for his cultural efforts. A patron of artwork and literature, Ashurbanipal was deeply interested in the ancient literary culture of Mesopotamia. Over the course of his long reign, Ashurbanipal utilised the massive resources at his disposal to construct the Library of Ashurbanipal, a collection of texts and documents of various different genres. Perhaps comprising over 100 000 texts at its height, the Library of Ashurbanipal was not surpassed until the construction of the Library of Alexandria. |

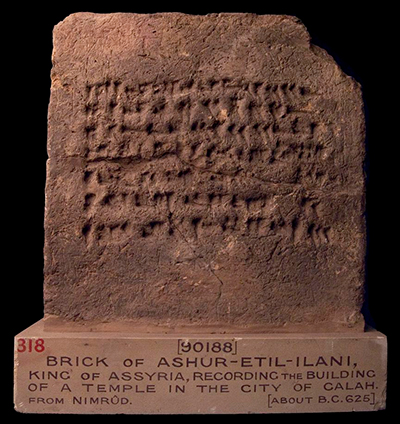

| Ashur-etil-ilani |

|

8 | 630 BC - 623 BC | The spread of inscriptions by Ashur-etil-ilani in Babylonia suggest that he exercised the same amount of control in the southern provinces as his father Ashurbanipal had, having a vassal king (Kandalanu) but exercising actual political and military power there himself. His inscriptions are known from all the major cities, including Babylon, Dilbat, Sippar and Nippur. Too few inscriptions of Ashur-etil-ilani survive to make any certain assumptions about his character. Excavations of his palace at Kalhu, one of the more important cities in the empire and a former capital, may indicate that he was less boastful than his father as it had no reliefs or statues similar to those that his predecessors had used to illustrate their strength and success. There are no records of Aššur-etil-ilāni ever conducting a military campaign or going on a hunt. His Kalhu palace was quite small with unusually small rooms by Assyrian royal standards. |

| Sin-shar-ishkun |

|

11 | 622 BC - 612 BC | On taking the throne, Sin-shar-ishkun was immediately faced by the revolt of one of his brother's chief generals, who attempted unsuccessfully to usurp the throne for himself. This failed attempt on the throne contributed to instability, and Sin-shar-ishkun lost control of Babylonia to Nabopolassar, who consolidated his power and formed the Neo-Babylonian Empire, restoring Babylonian independence after more than a century of Assyrian rule. This Neo-Babylonian Empire, and the newly formed Median Empire under Cyaxares, then invaded the Assyrian heartland. In 614 BC, the Medes captured and sacked Assur, the ceremonial and religious heart of the Assyrian Empire, and in 612 BC their combined armies attacked, brutally sacked, and razed Nineveh, the Assyrian capital. What doomed Assyria might have been the lack of an effective defensive plan for the Assyrian heartland, which had not been invaded in five hundred years, combined with having to face an enemy which aimed to outright destroy Assyria rather than simply conquer it. |

| Ashur-uballit II |

|

3 | 612 BC - 609 BC | Ashur-uballit II was the final ruler of Assyria, ruling from his predecessor Sin-shar-ishkun's death at the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC to his own defeat at Harran in 609 BC. He was possibly the son of Sin-shar-ishkun and likely the same person as a crown prince mentioned in inscriptions at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in 626 and 623 BC. Over the course of Sin-shar-ishkun's reign, the Neo-Assyrian Empire had been irreversibly weakened. However, Ashur-uballit rallied what remained of the Assyrian army at Harran where, bolstered by an alliance with Egypt, he ruled for three years. His identification as 'king of Assyria' comes from Babylonian sources. Contemporary Assyrian inscriptions suggest that the Assyrians saw Ashur-uballit as their legitimate ruler, but continued to refer to him as 'crown prince' seeing as he could not undergo the traditional Assyrian coronation ceremony at Assur and thus hadn't formally been bestowed with the kingship by the Assyrian chief deity, Ashur. His rule at Harran came to an end when the city was seized by Medo-Babylonian forces in 610 BC. Ashur-uballit's attempt at retaking it in 609 BC was repulsed whereafter he is no longer mentioned in contemporary chronicles, signalling the end of the ancient Assyrian monarchy. |

King Ashur-dan II

Map of Assyria 1392 CC - 934 BC

This map shows the extent of the Assyrian Empire when King Ashur-dan II came to the throne. He began the process of greatly extending the Empire.

Photo: Nel Weggelaar and Jan Kort, Amsterdam, repositorio.uca.edu.ar/bitstream/123456789/16108/1/assyrian-king-list.pdf

Reign of King Ashur-dan II (?) (934 BC - 912 BC)

Bronze statue

Bronze statue with inscription of King Ashur-dan, dedicated by a scribe of Ishtar of Arbeles, Shamshi-Bel. Tunic, shawl, fringe, belt, dagger.

The identity of the king is disputed: Deller and Grayson (RIMA 1 A.0.83.2001) identify him with Ashur-dan I (1178-1133 BC). The Louvre cartel indicated Ashur-dan II (933-912 BC) when the picture was taken. The Louvre database https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010120461 does not decide between Assurdan I, II or III.

Translation in RIMA 1 (pp. 307-308): 'To the goddess Ištar, the great mistress who dwells in Egašankalamma, mistress of Arbail, [his] mistress: For the life of Aššur-dān, king of [Assyria], his [lord], Šamšī-bēl, temple scribe, son of Nergal-nädin-ahi (who was) also scribe, for his life, his well-being, and the well-being of his eldest son, dedicated and devoted (this) copper statue weighing x minas. The name of this statue is: 'O goddess Istar, to you my ear (is directed)!'.

Details on the object: Statue of Ashurdan I, II or III (?), whose arms and head have disappeared. The king is standing, dressed in a long tunic and a fringed shawl, a dagger held in his belt; inscription on the bottom of the garment.

Height 295 mm, width 103 mm, thickness 53 mm.

Catalog: Urmiah region

Photo: Zunkir

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

King Adad-nirari II

Reign of King Adad-nirari II (911 BC - 891 BC)

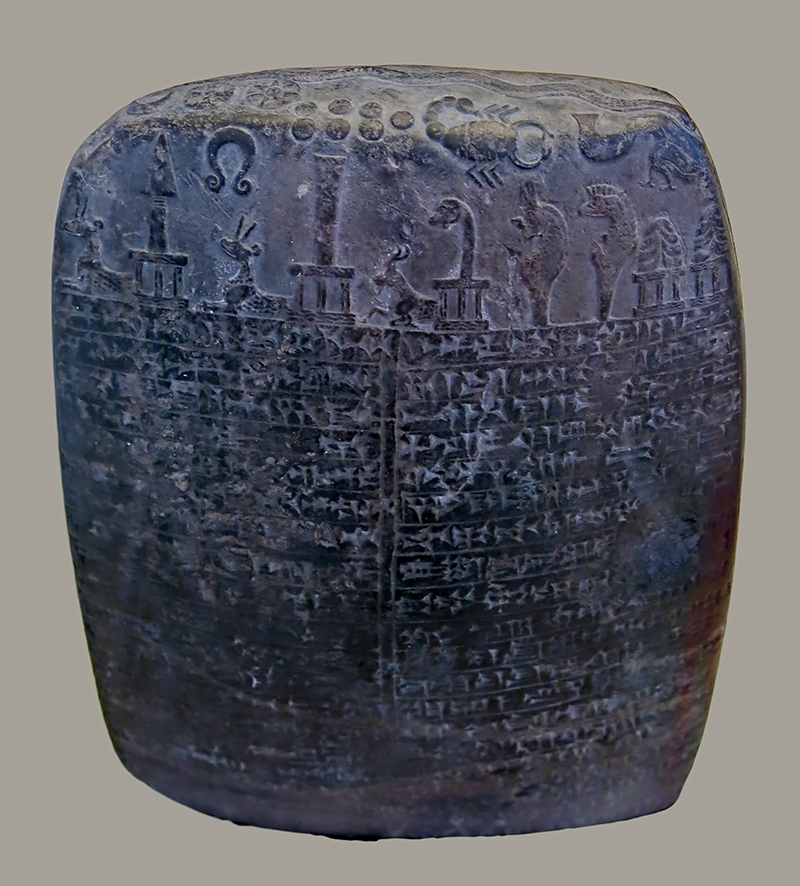

Basalt Pedestal

Basalt pedestal inscribed with name and titles of Adad-nirari II; probably supported a sacred pole in front of one of the temple shrines; hollow cylindrical column; inscribed.

Circa 900 BC.

Height 415 mm, width 285 mm, depth 270 mm.

Catalog: Basalt, Kouyunjik, BM/Big number 90853

Photo: Original, British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Stela, Middle Babylonian, 900 BC - 800 BC

Commemorative stone stela in the form of a boundary-stone (kudurru). The stela consists of a small boulder, on one face of which a fiat panel has been sunk, leaving figures and symbols standing out within it in low relief. The greater part of the inscription has been carved upon the flat surface of the panel, but the last seven lines extend below the panel to the base of the stone.

The stela is set up in honour of Adad-etir, the dagger-bearer of Marduk, by his eldest son. The name Marduk-balatsu-ikbi, which occurs in l. 4, is that of Adad-etir's son, not the name of the king to whom Adad-etir owed allegiance; and the two figures standing on the lower ledge of the panel represent Adad-etir and his eldest son, not Adad-etir and the king. The stele is closely related to a kudurru, since it is protected by carved symbols and by the addition of imprecatory clauses to the text. These symbols include (1) winged solar disc; (2) crescent; and (3) lion-headed mace upon a pedestal.

Findspot: Marduk Temple (Babylon)

Diameter 127 mm, height 380 mm, thickness 127 mm, width 270 mm.

Inscription translation of cuneiform: (1) (This) image of Adad-etir, the dagger-bearer of Marduk, (2) adorned by Sin, Shamash, and Nergal, (3) who fears Nabu and Marduk, who owes allegiance (4) to the king, his lord, Marduk-balatsu-ikbi, (5) his eldest son, has fashioned, (6) and for future days, (7) for his seed and his posterity, (8) has set up. (9) Whosoever in days to come (10) the image (11 f.) or this memorial-stone (13) shall destroy, (14) or by means of (15) a crafty device shall cause them to disappear, (16) may Marduk, the great lord, in anger (17) look upon him, and his name and his seed (18) may he cause to disappear! May Nabu, the scribe of all, (19) curtail the long number of his days! (20) But may the man who protects it be satisfied with the fulness of life!

Inscription note: Dedication in honour of Adad-etir, dagger-bearer of Marduk, by his son Marduk-balassu-iqbi; the text invokes curses on anyone who may deface it.

Curator's comments:

Commemorative stone stela; this object has some of the characteristics of a kudurru, including curses on anyone who may deface it, but it was set up in honour of a private individual, an official in the Marduk temple, by his son. The figures represent father and son together, and their shaven heads show that they are both priests, it being normal in ancient Mesopotamia for a son to adopt his father's profession

There are three divine symbols above the two priests: a winged solar disc representing the sun-god Shamash, a crescent of the moon-god Sin and a lion-headed mace on a pedestal.

The cuneiform inscription includes curses on anyone who may deface the stela. It translates: 'May Marduk, the great lord, in anger look upon him, and his name and his seed may he cause to disappear. May Nabu, the scribe of all, curtail the number of his days. But may the man who protects it be satisfied with the fullness of life.'

Since the fourth line of the inscription, taken from its context, contains the words 'the king his lord Marduk-balatsu-ikbi,' the stele has been traditionally assigned to the reign of Marduk-balatsu-ikbi, king of Babylon about 830 B.C.

That the two figures do not represent Adad-etir paying homage to his king is sufficiently obvious, from the absence of any royal headdress and other royal insignia from the taller figure. Further, the phrase 'ka-rib šarri-šu' is simply a descriptive title, on a par with 'si-mat (ilu)Sin (ilu)Šamaš u (ilu)Nergal' and 'pa-liḫ (ilu)Nabû u (ilu)Marduk'; the three phrases describe Adad-etir's personal endowments and his correct attitude towards divine and human authority. The writer merely refers to Adad-etir's loyalty: the name of the reigning king is immaterial and is therefore omitted.

On the other hand, Adad-etir's eldest son, who set up the stele as an act of piety, was not likely to omit his own name; and in the sculptured figures he represents himself paying homage to his father. It may be noted that the figures are dressed precisely alike, the only difference being that the father is taller than the son. Each raises one hand and rests the other on the handle of the dagger in his belt.

This stela comes from the Temple of Marduk in Babylon. It is a commemorative monument set up in honour of a private individual called Adad-etir. He was an official in the temple, known as 'the dagger bearer', and this stela was erected by his son Marduk-balassu-iqbi. The figures carved in relief on the front represent the father and son together. Their shaven heads show that they are both priests, it being normal in ancient Mesopotamia for a son to adopt his father's profession. There are three divine symbols above the two priests: a winged solar disc representing the sun-god Shamash, a crescent of the moon-god Sin and a lion-headed mace on a pedestal.

Associated names:

Named in inscription: Adad-Etir (temple official)

Named in inscription: Marduk-balassu-iqbi (Dedicator of stela)

Named in inscription: Marduk

Named in inscription: Nabu

Named in inscription: Sin

Named in inscription: Shamash

Associated places

Named in inscription: Marduk Temple (Babylon)

Asia: Middle East: Iraq: Iraq, South: Marduk Temple (Babylon)

Catalog: Diorite or granite, ME 90834

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: © Card with the display at the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

King Tukulti-Ninurta II

Reign of King Tukulti-Ninurta II (890 BC - 884 BC)

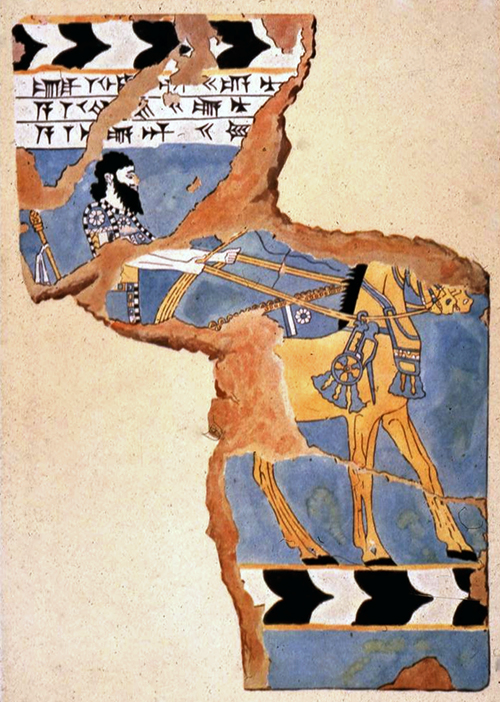

Wall-tile

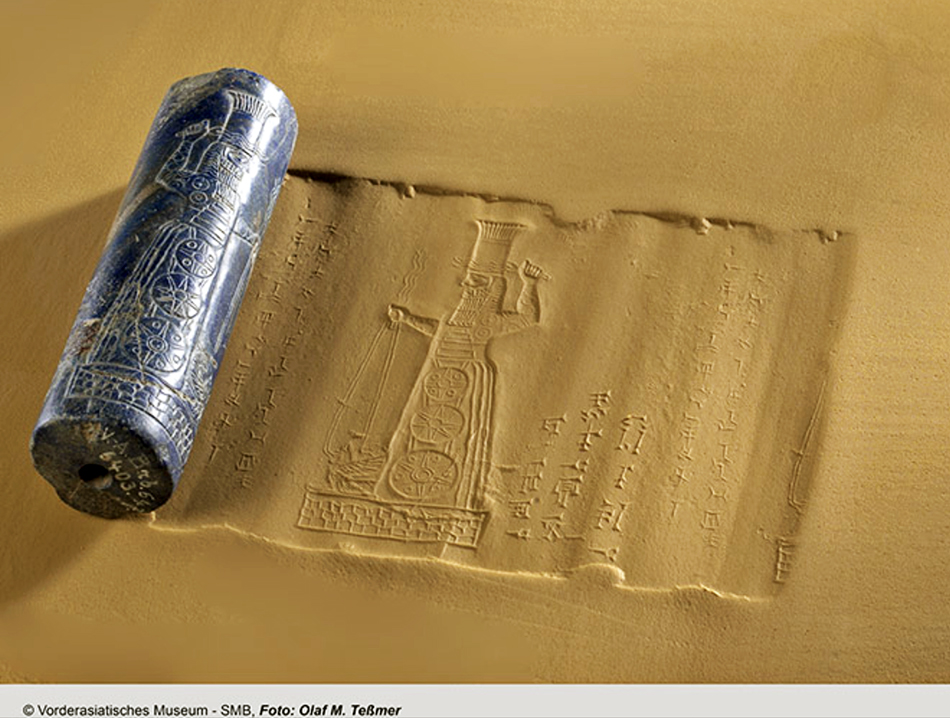

Glazed wall-tile of fired clay showing a charioteer. There is a border of chevrons top and bottom and a cuneiform inscription.

Length 665 mm, width 465 mm, thickness 65 mm.

There is a painted inscription containing the titles and genealogy of King Tukulti-Ninurta II.

Tukulti-Ninurta consolidated the gains made by his father over the Neo-Hittites, Babylonians and Arameans, and successfully campaigned in the Zagros Mountains of Iran, subjugating the newly arrived Iranian peoples of the area, the Persians and Medes, during his brief reign. Tukulti-Ninurta II was victorious over Ammi-Ba'al, the king of Bit-Zamani, and then entered into a treaty with him, as a result of which Bit-Zamani became an ally, and in fact a vassal of Assyria. Tukulti-Ninurta II developed both Nineveh and Assur, in which he improved the city walls, built palaces and temples and decorated the gardens with scenes of his military achievements.

Catalog: Glazed pottery, Ashur, BM/Big number 115705

Photo: Original, British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Additional text: Wikipedia

Assyrian Palaces

Artist’s impression of Assyrian palaces from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853.

Nineveh, also known in early modern times as Kouyunjik, was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern bank of the Tigris River and was the capital and largest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, as well as the largest city in the world for several decades. Today, it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and the country's Nineveh Governorate takes its name from it.

It was the largest city in the world for approximately fifty years until the year 612 BC when, after a bitter period of civil war in Assyria, it was sacked by a coalition of its former subject peoples including the Babylonians, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. The city was never again a political or administrative centre, but by Late Antiquity it was the seat of a Christian bishop. It declined relative to Mosul during the Middle Ages and was mostly abandoned by the 13th century AD.

Its ruins lie across the river from the historical city center of Mosul, in Iraq's Nineveh Governorate. The two main tells, or mound-ruins, within the walls are Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell Nabī Yūnus, site of a shrine to Jonah, the prophet who preached to Nineveh. Large amounts of Assyrian sculpture and other artifacts have been excavated there, and are now located in museums around the world.

Photo: Layard (1853) from a sketch by James Fergusson (1808–1886)

Proximal source: New York Public Library

Text: Wikipedia

Restoration of a hall in an Assyrian Palace.

Photo: Layard (1849)

Proximal source: New York Public Library

Nineveh - Mashki Gate

The reconstructed Mashki Gate of Nineveh. It has since been destroyed by the Islamic State.

Photo: Omar Siddeeq Yousif

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

Proximal Source: Wikipedia

King Ashurnasirpal II

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Head of King Ashurnasirpal II

Assyrian, about 883 - 859 BC. From Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room S, door e, panel 1.

Circa 865 BC - 860 BC

Wall panel of the head of king Ashurnasirpal II.

Height 597 mm, width 660 mm

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city (original Assyrian name Kalhu, biblical name Calah) located in Iraq, 30 kilometres south of the city of Mosul, and 5 kilometres south of the village of Selamiyah, in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a major Assyrian city between approximately 1350 BC and 610 BC.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, Nimrud, North-West Palace BM/Big number 135156

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Additional text: Wikipedia

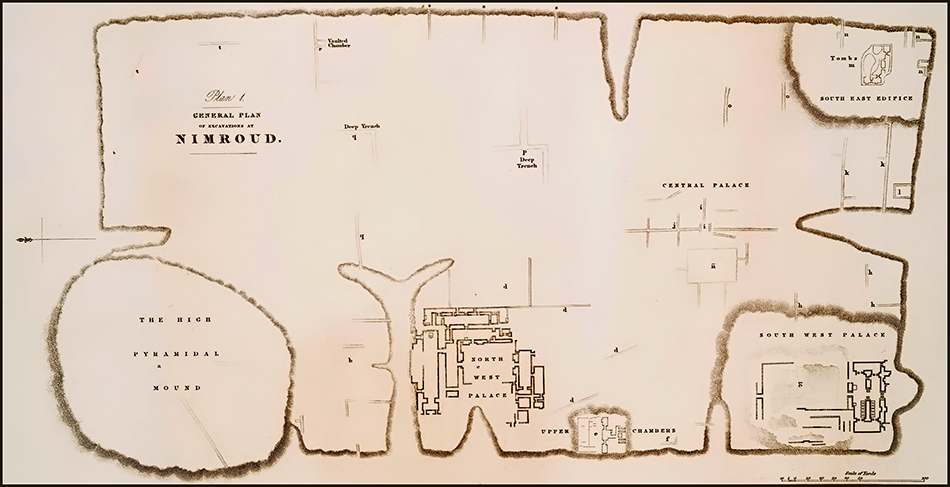

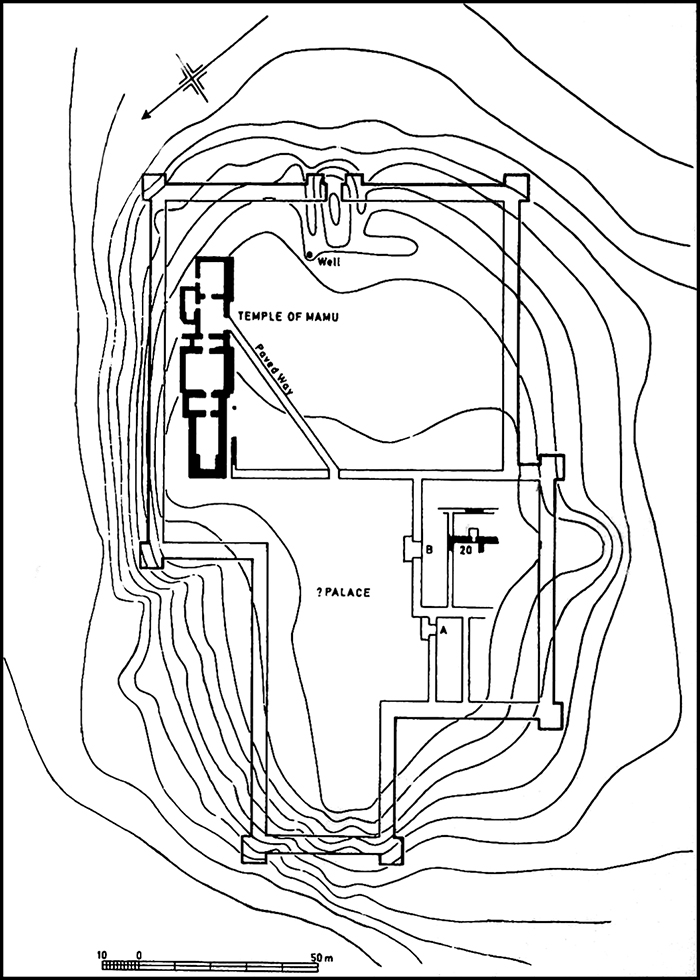

Plan I, General Plan, Nimrud.

Photo: Layard (1849)

Proximal source: New York Public Library

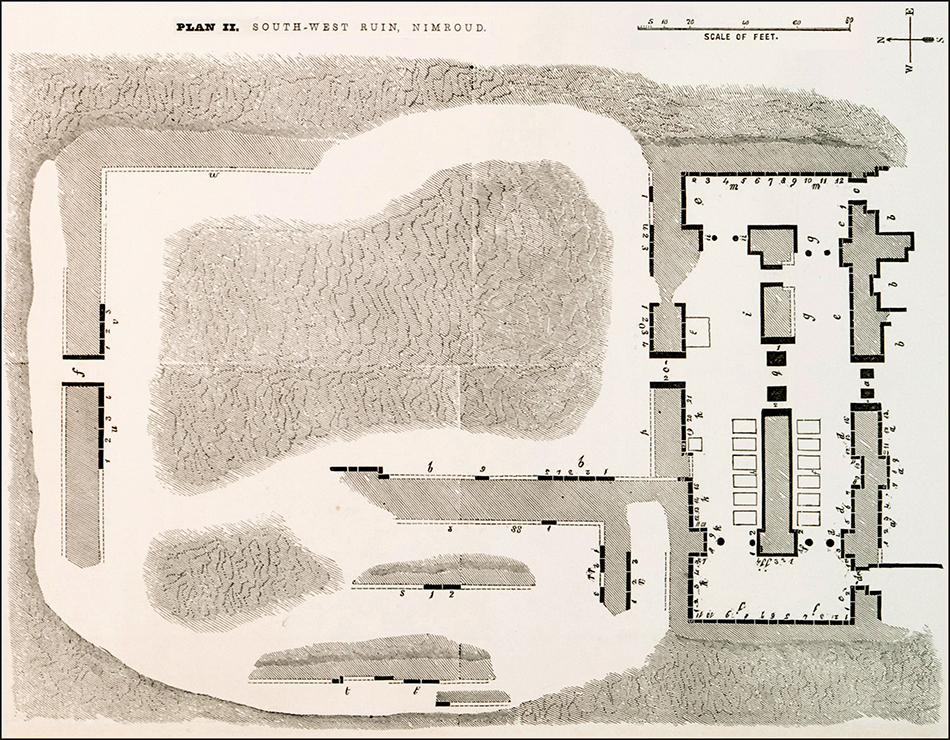

Plan II, South West Ruin / Palace, Nimrud.

( This image has been rotated 180 ° to agree with the general plan above - Don )

Photo: Layard (1849)

Proximal source: New York Public Library

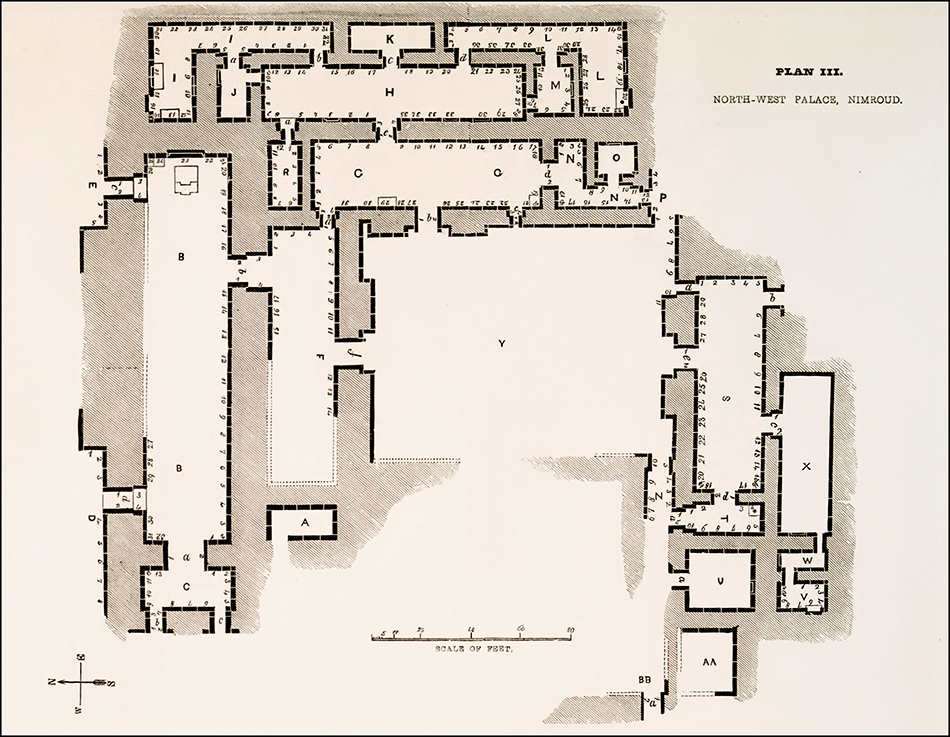

Plan III, North-West Palace, Nimrud.

Photo: Layard (1849)

Proximal source: New York Public Library

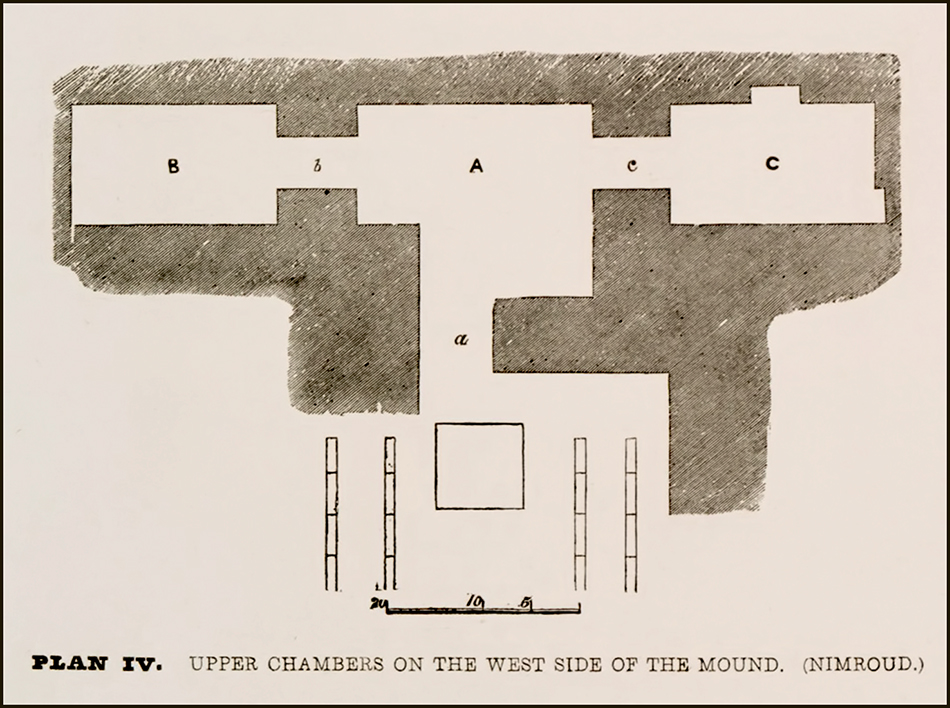

Plan IV, Upper Chambers on the West Side of the Mound, Nimrud.

Photo: Layard (1849)

Proximal source: New York Public Library

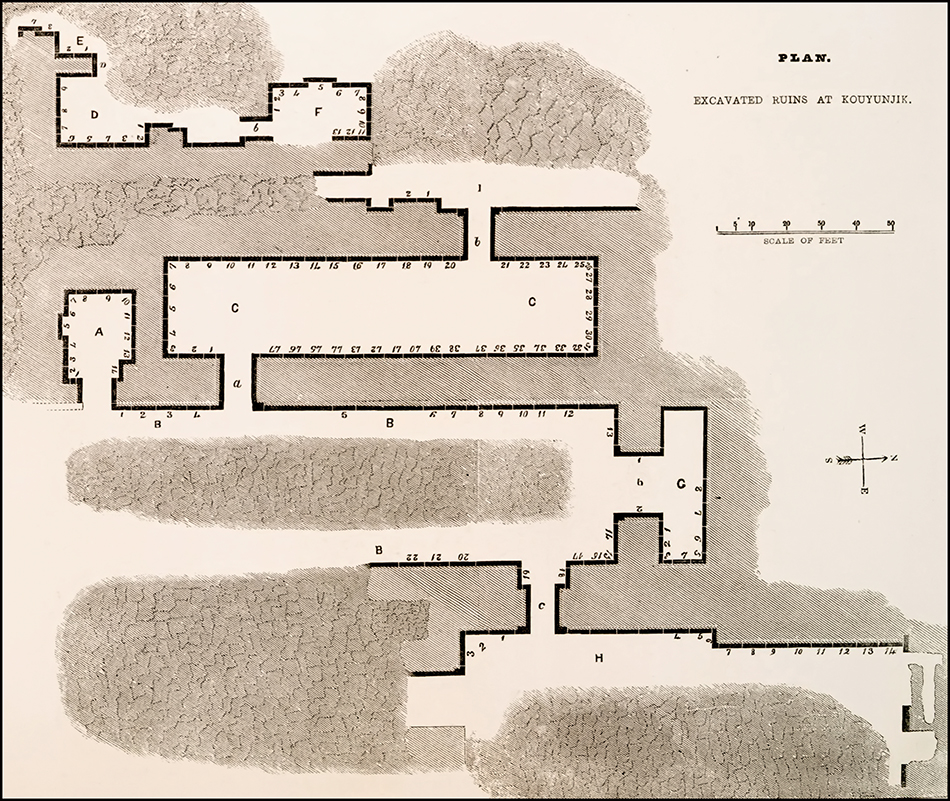

Plan, Excavated ruins at Nineveh (Kouyunjik).

Photo: Layard (1849)

Proximal source: New York Public Library

9th century BC (late Assyrian)

Inlay of a Cow Suckling a Calf

Some of the most elaborate ivory works have been discovered in the Kalhu (present-day Nimrud). These objects were brought from Syrian and Phoenician workshops to the Neo-Assyrian court. Egyptianising style and Egyptian motifs were quite popular among those artists. Large quantities of such ivory works were excavated in special store rooms in Nimrud, particularly in Fort Shalmaneser. This inlay displays a typical Egyptian motif, which may be related to Hathor, the Egyptian goddess who often took the form of a cow and suckled royal infants. The proportions and compact composition are characteristic of the ivory-carving schools of northern Syria.

Dimensions 5 × 10 × 2 cm.

Photo: Walters Art Museum

Proximal source: Wikipedia

Permission: This work is free and may be used by anyone for any purpose

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Winged human headed lion.

Assyrian, about 883 - 859 BC. From Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room G, door b, panel 2.

This protective spirit guarded the entrance into what may have been a banquet hall. The pair to it is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York ( see below - Don ).

Gypsum alabaster wall panel relief; winged human headed lion facing right; protective spirit; guarded entrance; inscription.

( The three 'horns' encircling the crown indicate that the wearer was of god-like status - Don )

Gypsum alabaster is a fine-grained, massive gypsum that has been used for centuries for statuary, carvings, and other ornaments. It normally is snow-white and translucent but can be artificially dyed; it may be made opaque and similar in appearance to marble by heat treatment.

Height 3170 mm, length 2810 mm.

Discovered by Layard at the beginning of 1847. It was placed on a raft and despatched from Nimrud towards the end of April 1847. It arrived at Basra, Iraq's main port with river access to the Persian Gulf, before the end of May. It was too heavy for further transport until loaded onto the Lynch & Co. sailing-ship 'Apprentice', arriving in London at the end of September 1850.

Catalog: Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room G, door b, panel 2. BM/Big number 118873

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Additional text: Encyclopedia Britannica

( I have rounded all the dimensions on this page to the nearest whole unit. Many of the dimensions were originally in British Imperial Units, and were transformed into Metric units at some point, which introduced spurious digits - Don )

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Winged human headed lion.

Assyrian, about 883 - 859 BC. From Nimrud.

This protective spirit guarded the entrance into what may have been a banquet hall.

This sculpture is the pair to the one in the British Museum, above.

From the ninth to the seventh century B.C., the kings of Assyria ruled over a vast empire centred in northern Iraq. The great Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 BC), undertook a vast building program at Nimrud, ancient Kalhu. Until it became the capital city under Ashurnasirpal, Nimrud had been no more than a provincial town.

The new capital occupied an area of about nine hundred acres, around which Ashurnasirpal constructed a mudbrick wall that was 120 feet thick, 42 feet high, and five miles long. In the southwest corner of this enclosure was the acropolis, where the temples, palaces, and administrative offices of the empire were located. In 879 BC Ashurnasirpal held a festival

for 69 574 people to celebrate the construction of the new capital, and the event was documented by an inscription that read: 'the happy people of all the lands together with the people of Kalhu — for ten days I feasted, wined, bathed, and honoured them and sent them back to their homes in peace and joy.'

The so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the surface of most of the reliefs described Ashurnasirpal's palace: 'I built thereon [a palace with] halls of cedar, cypress, juniper, boxwood, teak, terebinth, and tamarisk as my royal dwelling and for the enduring leisure life of my lordship.' The inscription continues: 'Beasts of the mountains and the seas, which I had fashioned out of white limestone and alabaster, I had set up in its gates. I made it [the palace] fittingly imposing.'

Among such stone beasts is the human-headed, winged lion (lamassu) pictured here. The horned cap attests to its divinity, and the belt signifies its power. The sculptor gave these guardian figures five legs so that they appear to be standing firmly when viewed from the front but striding forward when seen from the side. Lamassu protected and supported important doorways in Assyrian palaces.

Dimensions: 311 x 62 x 277 cm, 7257 kg

Catalog: Medium: Gypsum alabaster, Accession Number: 32.143.2

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932

Photo and text: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322609

Permission: Public Domain

Source: Original, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Winged human headed bull.

Assyrian, about 883 - 859 BC. From Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room S, door e, panel 1.

This protective spirit of a winged human headed bull facing left guarded the entrance into what may have been the king's private apartments. The pair to it is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. ( see below - Don ).

Height 309 cm, length 315 cm. An inscription records the name, titles and conquests of Ashurnasirpal II.

Catalog: Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room S, door e, panel 1. BM/Big number 118872

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Winged human headed bull (lamassu).

Assyrian, about 883 - 859 BC. From Nimrud, the North-West Palace.

From the ninth to the seventh century B.C., the kings of Assyria ruled over a vast empire centred in northern Iraq. The great Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 BC), undertook a vast building program at Nimrud, ancient Kalhu. Until it became the capital city under Ashurnasirpal, Nimrud had been no more than a provincial town.

The new capital occupied an area of about nine hundred acres, around which Ashurnasirpal constructed a mudbrick wall that was 120 feet thick, 42 feet high, and five miles long. In the southwest corner of this enclosure was the acropolis, where the temples, palaces, and administrative offices of the empire were located. In 879 B.C. Ashurnasirpal held a festival for 69 574 people to celebrate the construction of the new capital, and the event was documented by an inscription that read: 'the happy people of all the lands together with the people of Kalhu—for ten days I feasted, wined, bathed, and honoured them and sent them back to their home in peace and joy.'

The so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the surface of most of the reliefs described Ashurnasirpal's palace: 'I built thereon [a palace with] halls of cedar, cypress, juniper, boxwood, teak, terebinth, and tamarisk [?] as my royal dwelling and for the enduring leisure life of my lordship.' The inscription continues: 'Beasts of the mountains and the seas, which I had fashioned out of white limestone and alabaster, I had set up in its gates. I made it [the palace] fittingly imposing.'

Among such stone beasts is the human-headed, winged bull pictured here. The horned cap attests to its divinity, and the belt signifies its power. The sculptor gave these guardian figures five legs so that they appear to be standing firmly when viewed from the front but striding forward when seen from the side. Lamassu protected and supported important doorways in Assyrian palaces.

Dimensions 314 x 67 x 310 cm, 7257 kg.

Catalog: Medium: Gypsum alabaster, Accession Number: 32.143.1

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932

Photo and text: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322608

Permission: Public Domain

Source: Original, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

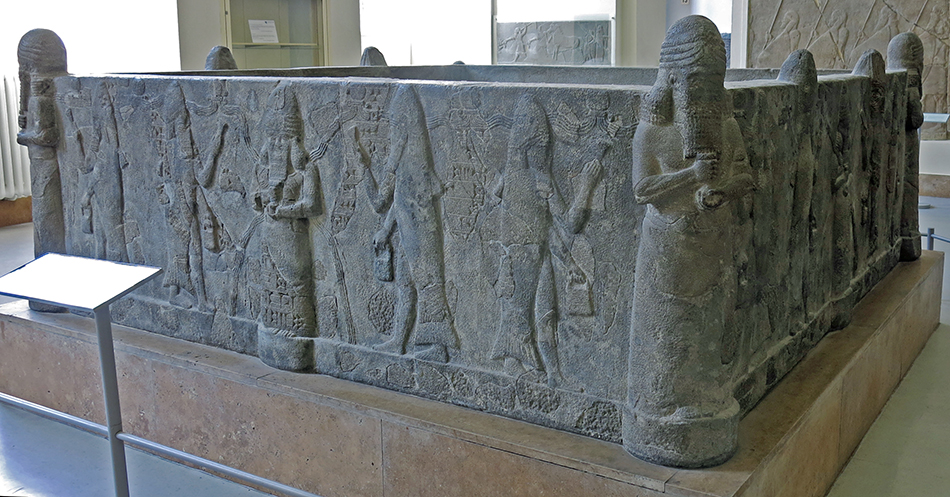

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Winged human headed lions.

Assyrian, about 883 - 859 BC. From Nimrud.

The human-headed, winged lion sculptures in the Pergamon Museum, known as Lamassu, are remarkable examples of Assyrian art and architecture.

Each Lamassu features a human head, typically depicted with a regal beard and a high, elaborate headdress. The human head is often portrayed with a serene and dignified expression, symbolising divine protection and wisdom.

The body of the Lamassu is that of a lion, symbolising strength and courage. The lion’s muscular form is powerfully rendered, showcasing the artist’s skill in representing physicality and grace.

The Lamassu is adorned with large, intricately detailed wings. The wings are spread wide, adding to the sculpture’s sense of majesty and divine authority. The feathers are carefully carved, demonstrating the craftsmanship of Assyrian artists.

The creature typically has the legs of a lion, as here, but in some depictions, it stands on a pair of legs that combine that of a lion and sometimes even a human-like structure, giving the sculpture a sense of movement and stability.

The sculptures are often highly detailed with elaborate patterns and motifs, including intricate carvings on the wings and body. These details reflect the high level of artistry and the importance of the Lamassu as protective figures.

Lamassu statues served as protective deities and were placed at the entrances of palaces and important buildings. They were intended to ward off evil and ensure the safety and sanctity of the spaces they guarded. Their imposing size and elaborate design conveyed the power and authority of the Assyrian rulers who commissioned them.

The Lamassu sculptures in the Pergamon Museum come from the Assyrian city of Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), which was established by King Sargon II. The city and its art were designed to project the king’s power and divine favor. The Lamassu are part of the museum's extensive collection of Assyrian artefacts, providing valuable insight into ancient Near Eastern culture and artistry.

These statues are celebrated for their grandeur and the skill with which they were crafted, making them a highlight of the Pergamon Museum’s collection.

Note that the sculptures were meant to be seen from one side or from straight ahead, so that from some perspectives five legs can be seen.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Pergamon Museum, Berlin

Text: Various sources

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Winged human headed lion.

These are a pair of lions, 118802 above, and 118801 below, that flanked a doorway in the throne room of Ashurnasirpal II (883 BC - 859 BC). They provided magical protection for the building and they wear ropes, like other protective lions. The five legs suggest that they were intended to be viewed from the front or the side, not from an angle.

These gypsum statues, circa 865 BC - 860 BC of a human headed winged lion, flanked the doorway of the throne room of the North West palace of Ashurnasirpal in Nimrud. They helped provide magical protection.

118802: Height 3500 mm, length 3710 mm.

118801: Height: 3500 mm, length 3630 mm.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Catalog: BM/Big numbers 118801, 118802

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

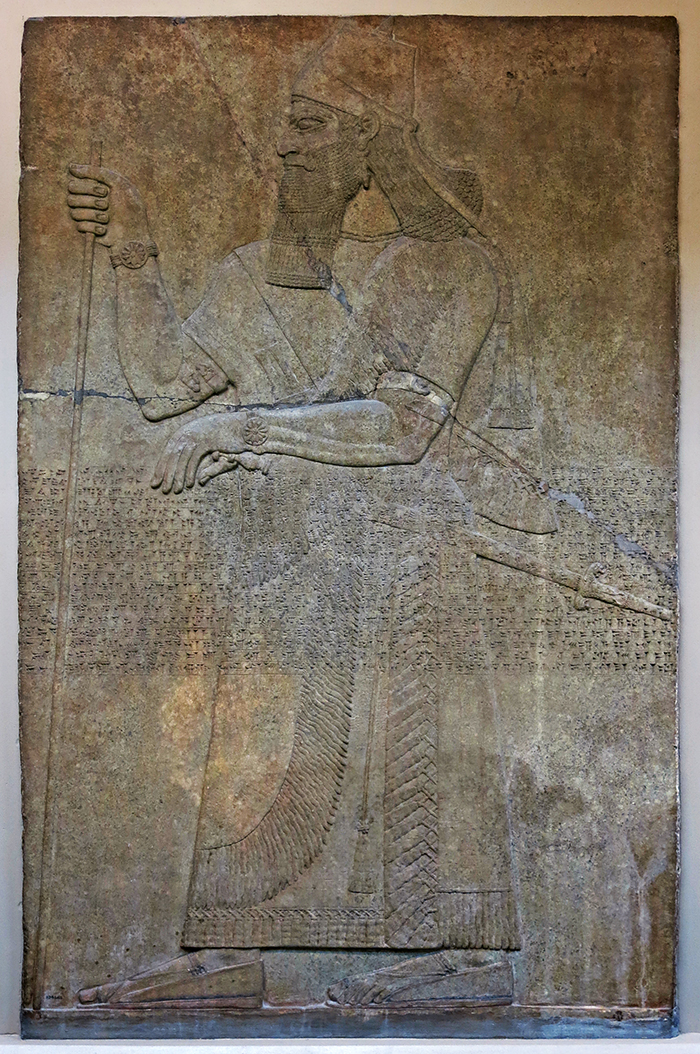

King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

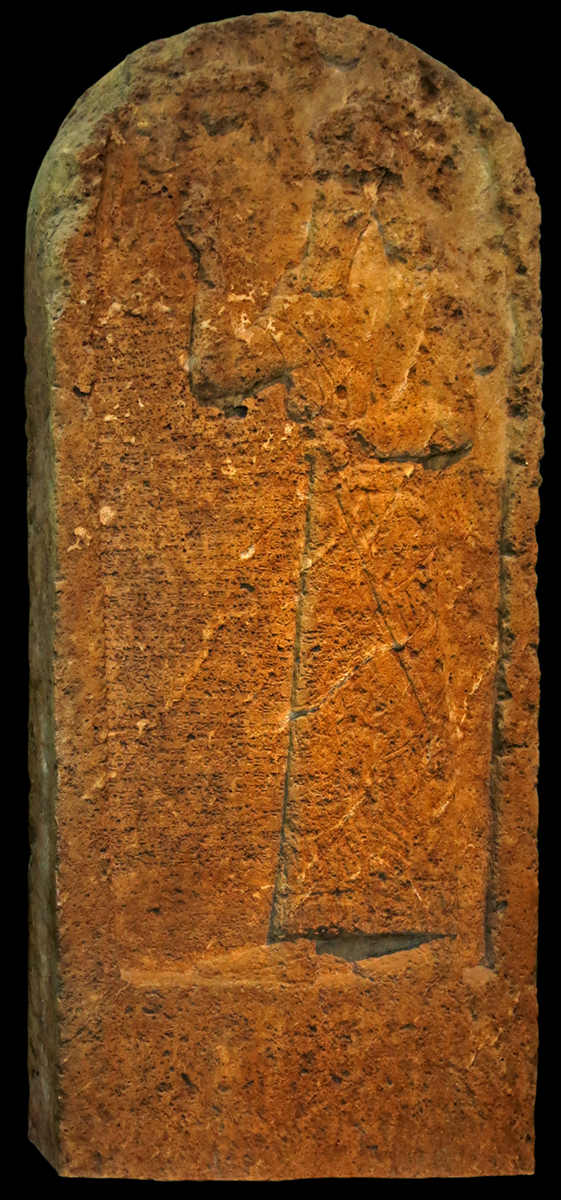

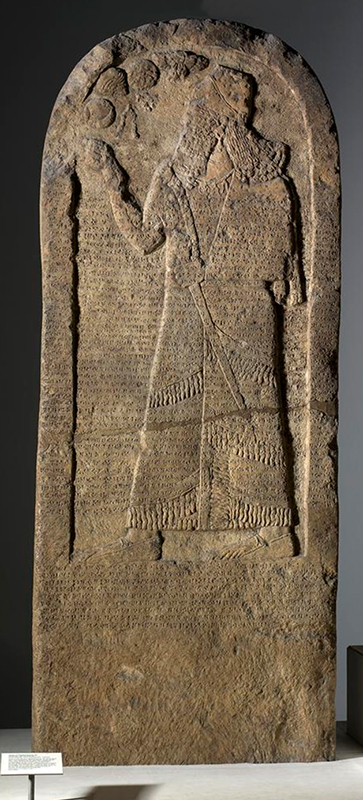

Stela

This stela shows the king worshipping, with his right hand raised to the symbols of his gods.

The text describes his attack around the upper Tigris river in 879 BC, near Diyarbakir. This stela was probably then raised in one of the Assyrian ruled towns. Ashurnasirpal's son also set up a stela at Kurkh.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Catalog: BM/Big number 11883

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

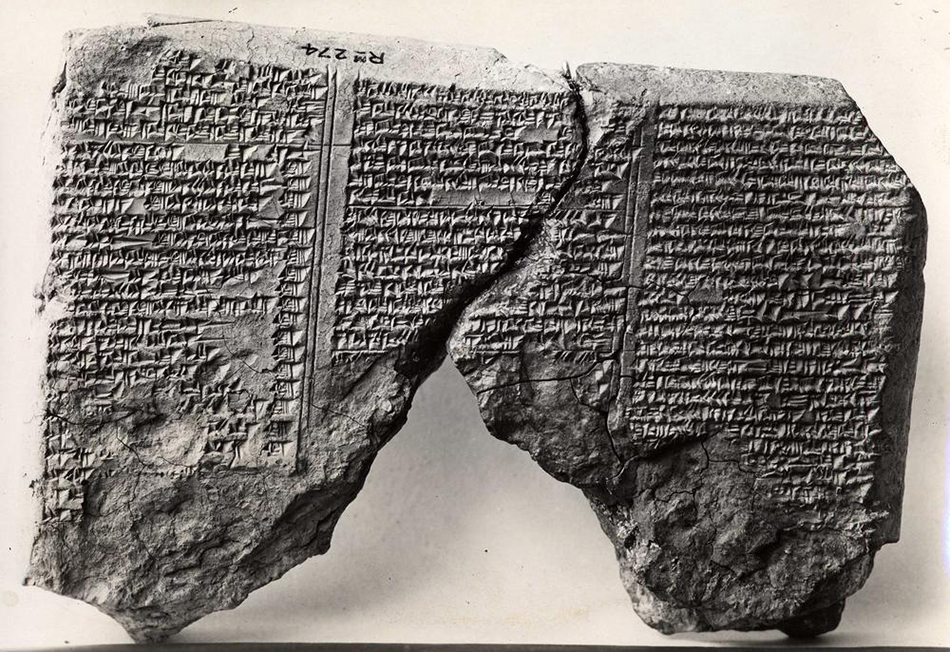

The Standard Inscription of Ahurnasirpal

The so-called Standard Inscription of Ashurnasirpal was carved across the centre of every wall panel in the North-West Palace, forming a decorative band around each room. Occasionally, on narrow panels, part of the text was omitted. Otherwise there was no significant variation and the catalogue of royal titles, claims and achievements was simply repeated over and over again.

Palace of Ashurnasirpal, priest of Ashur, favourite of Enlil and Ninurtya, beloved of Anu and Dagan, the weapon of the great gods, the mighty king, king of the world, king of Assyria; son of Tukulti-Ninurta, the great king, the mighty king, king of the world, king of Assyria; the valiant man, who acts with the support of Ashur, his lord, and has no equal among the princes of the four quarters of the world; the wonderful shepherd who is not afraid of battle; the great flood which none can oppose; the king who makes those who makes those who are not subject to him submissive; who has subjugated all mankind; the mighty warrior who treads on the neck of his enemies, tramples down all foes, and shatters the forces of the proud; the king who acts with the support of the great gods, and whose hand has conquered all lands, who has subjugated all the mountains and received their tribute, taking hostages and establishing his power over all countries.Text above: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

When Ashur, the lord who called me by name and has made my kingdom great, entrusted his merciless weapon to my lordly arms, I overthrew the widespread troops of the land of Lullume in battle. With the assistance of Shamash and Adad, the gods who help me, I thundered like Adad the destroyer over troops of the Nairi lands, Habhi, Shubaru, and Nirib. I am the king who has brought into submission at his feet the lands from beyond the Tigris to Mount Lebanon and the Great Sea (the Mediterranean), the whole of the land of Laqe, the land of Suhi as far as Rapiqu, and whose hand has conquered from the source of the river Subnat to the land of Urartu.

The area from the mountain passes of Kirruri to the land of Gilzanu, from beyond the Lower Zab to the city of Til-sha-Zabdani, Hirimu and Harutu, fortresses of the land of Karduniash (Babylonia), I have restored to the borders of my land. From the mountain passes of Babite to the land of Hashmar I have counted the inhabitants of my land. Over the lands which I have subjugated I have appointed my governors, and they do obeisance.

I am Ashurnasirpal, the celebrated prince, who reveres the great gods, the fierce dragon, conqueror of the cities and mountains to their furthest extent, king of rulers who has tamed the stiff-necked peoples, who is crowned with splendour, who is not afraid of battle, the merciless champion who shakes resistance, the glorious king, the shepherd, the protection of the whole world, the king, the word of whose mouth destroys mountains and seas, who by his lordly attack has forced fierce and merciless kings from the rising to the setting sun to acknowledge one rule.

The former city of Kalhu (Nimrud) which Shalmaneser king of Assyria, a prince who preceded me, had built, that city had fallen into ruins and lay deserted. That city I built anew. I took the peoples from whom my hand had conquered from the lands which I had subjugated, from the land of Suhi, from the whole of the land of Laqe, from the city of Sirqu on the other side of the Euphrates, from the furthest extent of the land of Zamua, from teh Bit-Adini and the land of Hatte, and from Lubarna, king of the island of Patina, and made them settle there.

I removed the ancient mound and dug down to the water level. I sank the foundations 120 brick courses deep. A palace with walls of cedar, cypress, juniper, box-wood, meskannu-wood (Dalbergia sissoo, terbinth (Pistacia terebinthus) and tamarisk, I founded my royal residence for my lordly pleasure forever.

Creatures of the mountains and seas I fashioned in white limestone and alabaster, and set them up at its gates. I adorned it, and made it glorious, and set ornamental knobs of bronze around it. I fixed doors of cedar, cypress, juniper and meskannu-wood in its gates. I took in great quantities, and placed there, silver, gold, tin, bronze and iron, booty taken by my hands from the lands which I had conquered.

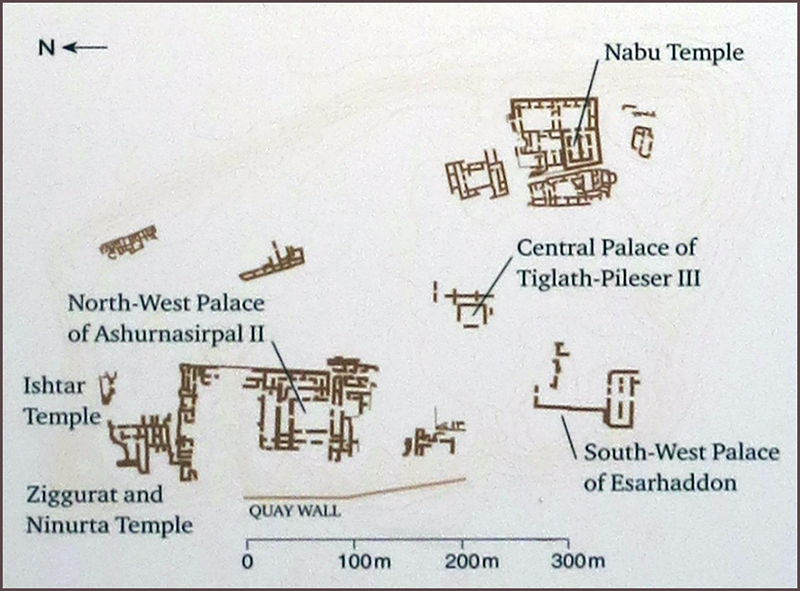

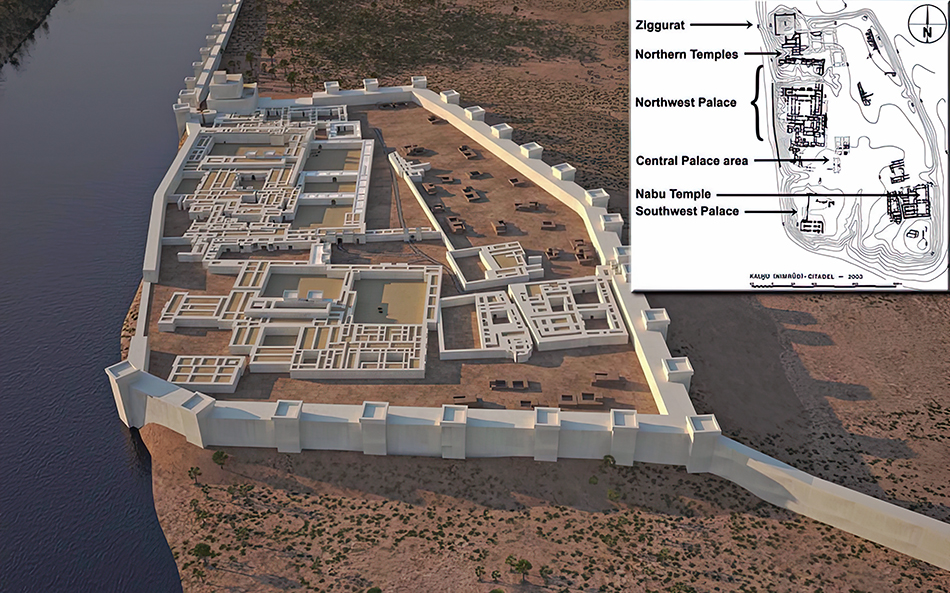

Plan of the citadel of Nimrud.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Poster with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Citadel of Nimrud.

Rendering of the citadel at Nimrud, extracted from the virtual world of the citadel created by Learning Sites; inset is a traditional plan of the same site.

Photo: © 2015 Learning Sites, Inc.

Source: Sanders (2015)

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883 BC - 859 BC)

Colossal Lion

Gypsum wall-panel relief showing a colossal lion, one of a pair, much damaged by fire, which guarded the entrance to the temple of Ishtar Sharrat-niphi; inscribed.

Circa 865 BC - 860 BC.

Height 2590 mm, length 3960 mm.

Records the name, titles and conquests of Ashurnasirpal II.

Guarded entrance to temple of Ishtar Sharrat-Niphu (Belit-Mati according to the record card)

Catalog: Gypsum, Temple of Ishtar Sharrat-niphi, 118895

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The largest and most extravagant party ever held

When Ashurnasirpal, king of Assyria, inaugurated the palace of Calah, a palace of joy and [erected with] great ingenuity, he invited into it Ashur, the great lord and the gods of his entire country, [he prepared a banquet of] 1000 fattened head of cattle, 1000 calves, 10000 stable sheep, 15000 lambs — for my lady Ishtar [alone] 200 head of cattle [and] 1000 sihhu-sheep — 1000 spring lambs, 500 stages, 500 gazelles, 1000 ducks, 500 geese, 500 kurku-geese, 1000 mesuku-birds, 1000 qaribu-birds, 10000 doves, 10000 sukanunu-doves, 10000 other [assorted] small birds, 10000 [assorted] fish, 10000 jerboa, 10000 [assorted] eggs,…10000 [jars of] beer, 10000 skins with wine, …1000 wood crates with vegetables, 300 [containers with] oil, …100 [containers with] fine mixed beer, …100 pistachio cones, ….

When I inaugurated the palace at Calah I treated for ten days with food and drink 47074 persons, men and women, who were bid to come from across my entire country, [also] 5000 important persons, delegates from the country Suhu, from Hindana, Hattina, Hatti, Tyre, Sidon, Gurguma, Malida, Hubushka, Gilzana, Kuma [and] Musasir, [also] 16000 inhabitants of Calah from all ways of life, 1500 officials of all my palaces, altogether 69574 invited guests from all the [mentioned] countries including the people of Calah; I [furthermore] provided them with the means to clean and anoint themselves. I did them due honors and sent them back, healthy and happy, to their own countries.

Source: “The Banquet of Ashurnasirpal II,” translated by A. Leo Oppenheim, in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed. with Supplement, edited by James B. Pritchard (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 558-561.

Taken from the following Internet site, now unavailable (28 Sept. 2004):

www.bol.ucla.edu/~szuchman/banquet_inscription.htm

Image: AI image using openart.ai

Text below from the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

The ancient state of Assyria lay in what is now northern Iraq. The sculptures above are from the reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 BC), a king whose military expeditions to the west reached the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, and helped lay the foundations for an empire that came to dominate the Near Eastern political landscape from the ninth through seventh centuries B.C. The king himself is depicted on one of the reliefs (32.143.4). Ashurnasirpal moved from the traditional Assyrian capital, Ashur, to Nimrud, and there built a new and spectacular palace, today called the Northwest Palace for its position on the site’s citadel. Texts survive describing the palace’s completion and inauguration, involving a banquet for almost 70 000 people. The number is probably exaggerated, but there is no doubt that this was a huge festival.

The inscription was discovered in a recess of courtyard E of the North-West Palace during the third season of the Nimrud excavations in 1951. A full account of the discovery is given in Chap. IV of Mallowan's Nimrud and its Remains. For the text and a first discussion of the stele one turns to the edition of D. J. Wiseman published in Vol. XIV of this Journal.

Since the publication of the stele in 1952, three new translations have appeared, namely, those of Jorgan Laessøe, A. L. Oppenheim, and A. K. Grayson, and a number of improvements to the text and interpretation have been made by Wolfgang Schramm, and, following collation, by J. N. Postgate. Despite these attentions, however, many problems still remain.

Text in the two paragraphs immediately above: adapted from www.cambridge.org/

Text below from Martha Carlin, sites.uwm.edu/carlin/ashurnasirpal-iis-banquet-inscription/

Ashurnasirpal II’s Banquet Inscription

Found near throne room in Northwest Palace of Kalhu

[This is] the palace of Ashurnasirpal, the high priest of Ashur, chosen by Enlil and Ninurta, the favorite of Anu and Dagan [who is] destruction personified among all the great gods – the legitimate king, the king of the world, the king of Assyria, son of Tukult-Ninurta, great king, ligitimate king, king of the world, king of Assyria [who was] the son of Adad-nirari, likewise great king, legitimate king, king of the world and king of Assyria – the heroic warrior who always acts upon trust- inspiring signs given by his lord Ashur and [therefore] has no rival among the rulers of the four quarters [of the world]; the shepherd of all mortals, not afraid of battle [but] an onrushing flood which brooks no resistance; the king who subdues the unsubmissive [and] rules over all mankind; the king who always acts upon trust-inspiring signs given by his lords, the great gods, and therefore has personally conquered all countries; who has acquired dominion over the mountain regions and received their tribute; he takes hostages, triumphs over all the countries from beyond the Tigris to the Lebanon and the Great Sea, he has brought into submission the entire country of Laqe and the region of Suhu as far as the town of Rapiqu; personally he conquered [the region] from the source of the Subnat River to Urartu.

I returned to the territory of my own country [the regions] from the pass [which leads to] the country Kirrure as far as Gilzani, from beyond the Lower Zab River to the town of Til-bari which is upstream of the land of Zamua – from Til-sha-abtani to Til-sha-sabtani – [also] Hirimu and Harrutu [in] the fortified border region of Babylonia [Karduniash]. I listed as inhabitants of my own country [the people living] from the pass of Mt. Babite to the land of Hashmar.

Ashur, the Great Lord, has chosen me and made a prounouncement concerning my world rule with his own holy mouth [as follows]: Ashurnasirpal is the king whose fame is power!

I took over again the city of Calah in that wisdom of mine, the knowledge which Ea, the king of the subterranean waters, has bestowed upon me, I removed the old hill of rubble: I dug down to the water level; I heaped up a [new] terrace [measuring] from the water level to the upper edge 120 layers of bricks; upon that I erected as my royal seat and for my personal enjoyment 7 beautiful halls [roofed with] boxwood, Magan-ash, cedar, cypress, juniper, boxwood and Magan-ash with bands of bronze; I hung them in their doorways; I surrounded them [the doors] with decorative bronze bolts; to proclaim my heroic deeds I painted on [the palaces’] walls with vivid blue paint how I have marched across the mountain ranges, the foreign countries and the seas, my conquests in all countries; I had lapis lazuli colored glazed bricks made and set [them in the wall] above their gates. I brought in people from the countries over which I rule, those who were conquered by me personally, [that is] from the country Suhi [those of] the town Great [?], from the entire land of Zamua, the countries Bit-Zamani and [Kir]rure, the town of Sirqu with is across the Euphrates, and many inhabitants of Laqe, of Syria and [who are subjects] of Lubarna, the ruler of Hattina; I settled them therein [the city of Calah].

I dug a canal from the Upper Zab River; I cut [for this purpose] straight through the mountains[s]; I called it Patti- hegalli [“Channel-of-Abundance”]; I provided the lowlands along the Tigris with irrigation; I planted orchards at [the city’s] outskirts, with all sorts of fruit trees.

I pressed the grapes and offered [them] as first fruits in a libation to my lord Ashur and to all the sanctuaries of my country. I [then] dedicated that city to my lord Ashur.

[I collected and planted in my garden] from the countries through which I marched and the mountains which I crossed, the trees [and plants raised from] seeds from wherever I discovered [them, such as]: cedars, cypress, simmesallu-perfume trees, burasu-junipers, myrrh-producing trees, dapranu-junipers, nut- bearing trees, date palms, ebony, Magan-ash, olive trees, tamarind, oaks, tarpi’u-terebinth trees, luddu-nut-bearing trees, pistachio and cornel-trees, mehru-trees, semur-trees, tijatu- trees, Kanish oaks, willows, sadanu-trees, pomegranates, plum trees, fir trees, ingirasu-trees, kamesseru-pear trees, supurgillu-bearing trees, fig trees, grape vines, angasu-pear trees, aromatic sumlalu-trees, titip-trees…. In the gardens in [Calah] they vied with each other in fragrance; the paths [in the garden were well kept], the irrigation weirs [distributed the water evenly]; its pomegranates glow in the pleasure garden like the stars in the sky, they are interwoven like grapes on the vine; …in the pleasure garden…in the garden of happiness flourished like [cedar trees]….

I erected in Calah, the center of my overlordship, temples such as those of Enlil and Ninurta which did not exist there before; I rebuilt in it the [following] temples of the great gods…. In them I established the [sacred] pedestals of these, my divine lords. I decorated them splendidly; I roofed them with cedar beams, made large cedar doors, sheathed them with bands of bronze, placed them in their doorways. I placed representations made of shining bronze in their doorways. I made [the images of] their great godheads sumptuous with red gold and shining stones. I presented them with golden jewelry and many other precious objects which I had won as booty.

I lined the inner shrine of my lord Ninurta with gold and lapis lazuli, I placed at his pedestal fierce ushumgallu-dragons of gold. I performed his festival in the months Shabatu and Ululu. I arranged for them [the materials needed for] scatter and incense offerings so that his festival in Shabatu should be one of great display. I fashioned a statue of myself as king in the likeness of my own features out of red gold and polished stones and placed it before my lord Ninurta.

I organised the abandoned towns which during the rule of my fathers had become hills of rubble, and had many people settle therein; I rebuilt the old palaces across my entire country in due splendour; I stored in them barley and straw.

Ninurta and Palil, who love me as [their] high priest, handed over to me all the wild animals and ordered me to hunt [them]. I killed 450 big lions; I killed 390 wild bulls from my open chariots in direct assault as befits a ruler; I cut off the heads of 200 ostriches as if they were caged birds; I caught 30 elephants in pitfalls. I caught alive 50 wild bulls, 140 ostriches [and] 20 big lions with my own…

I received five live elephants as tribute from the governor of Suhu [the Middle Euphrates region] and the governor of Lubda [SE Assyria toward Babylonia]; they used to travel with me on my campaigns. I organised herds of wild bulls, lions, ostriches and male and female monkys and had them breed like flocks [of domestic animals].

I added land to the land of Assyria, many people to its people.

Like most ancient Near Eastern palaces, the Northwest Palace was made of mud brick. Ashurnasirpal seems to have been the first Assyrian king to line his palace walls with stone bas-reliefs, and his inscriptions boast of finding and utilising the stone that made it possible. This stone, which could be quarried locally, is a gypsum, sometimes called alabaster (it is almost white when first cut) and colloquially known as 'Mosul marble' after the nearby modern city. The slabs are extremely heavy, and simply quarrying and transporting the stone for use in the palace was a major undertaking. Once in position, the carving of the reliefs, with their carefully modelled figures and perfectly smooth backgrounds, represented another enormous task. An inscription describing the king’s achievements, today called the Standard Inscription was carved across the centre of each panel. It seems likely that the repetition of the inscription, like that of the reliefs’ imagery, formed part of the magical protection of the palace and the king. Finally, the reliefs were brightly painted. Some pigment can still be seen in rare cases (31.72.1), and analysis of microscopic traces can sometimes reveal the original colours even when no paint is visible. Many of the figures in the reliefs wear clothes with embroidered patterns, rendered on the stone as fine engraving (1982.1188.4); these would originally have been picked out in contrasting colours.

Map of the central area of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Vorderasiatisches Museum, Ausführung: Christoph Forster, datalina

Source: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Pergamonmuseum

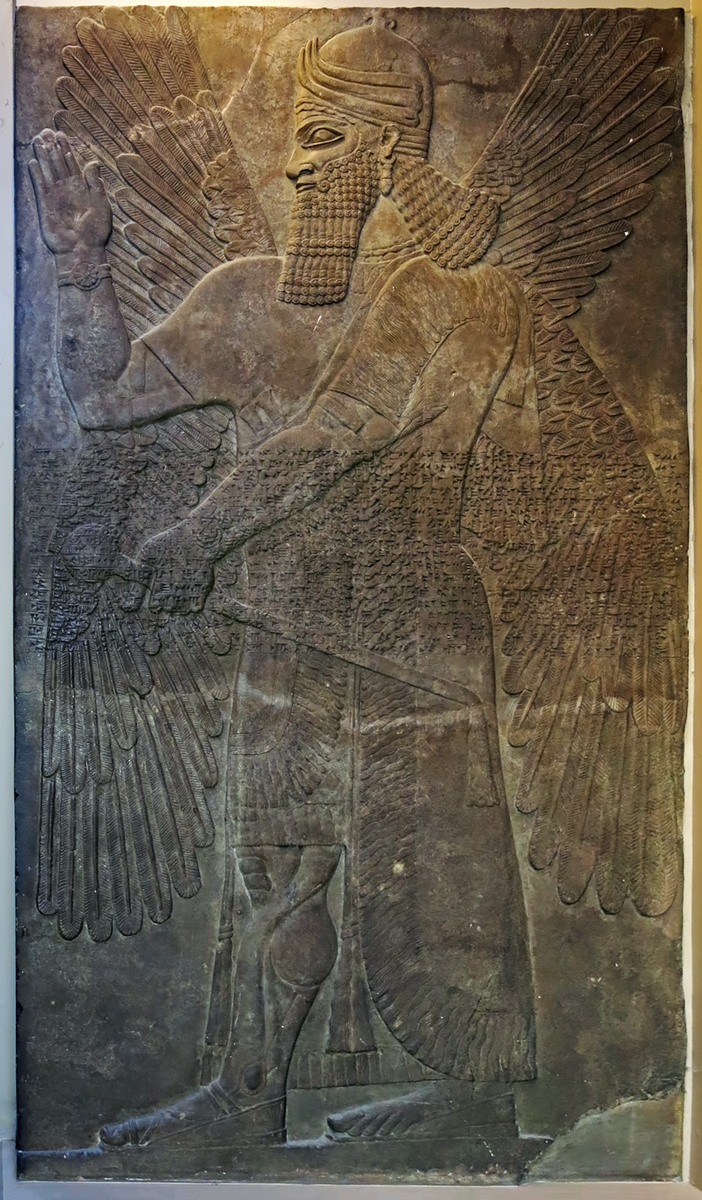

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Spirit

865 BC - 860 BC

Gypsum wall panel relief, of a winged human-headed horned protective spirit with right hand raised and a branch in the left hand, facing right. It guarded the door into what may have been royal bedroom.

Height 2286 mm, width 1067 mm, thickness 203 mm.

Catalog: Nimrud, North-West Palace, Assyrian Transept West, BM/Big number 118803

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Spirit

865 BC - 860 BC

Gypsum wall panel relief showing a four-winged protective spirit facing left, wearing a three-horned cap and holding a mace. It may be performing an act of worship. This wall panel guarded one of the doors into the royal throne room. It bears the Standard Inscription of Ashurnasirpal II.

Height 2311 mm, width 1321 mm.

Catalog: Nimrud, North-West Palace, BM/Big number 124530

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

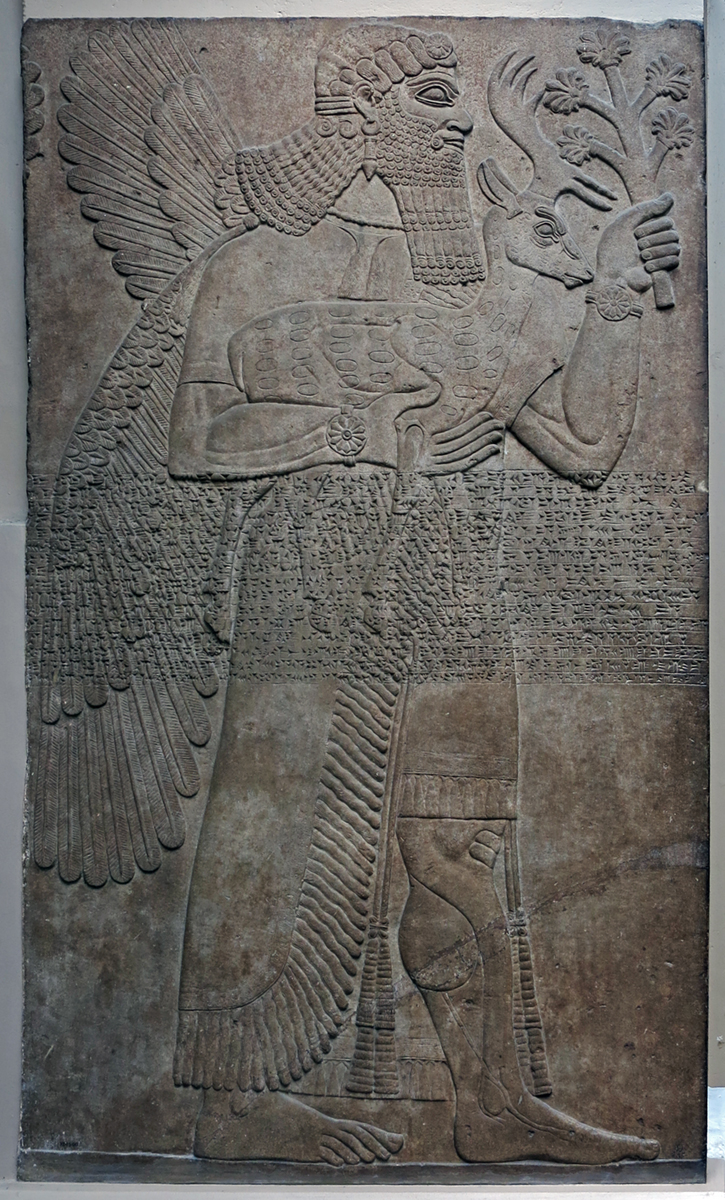

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Spirit

865 BC - 860 BC

Gypsum wall panel in relief. A winged eagle-headed protective spirit between sacred trees facing left, with an inscription.

The Sacred Trees were completed on adjoining panels. The one on the right is in Dresden, while the one on the left is lost.

Height 2134 mm, width 2184 mm, thickness 203 mm.

( Note that at the time of writing, May 2024, there is no image of this object available on the BM website - Don )

Catalog: From Nimrud, North-West Palace, Room F, panel 8. BM/Big number 118804

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Protective Spirit

Gypsum wall panel relief showing a protective spirit carrying a deer and a palm branch. This panel once guarded the door to the royal throne room. There is an inscription written in cuneiform script.

Circa 865 BC - 860 BC.

Height 2250 mm, width 1350 mm.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, Nimrud, North West Palace, Room B, Panel 30, BM/Big number 124560

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Don Hitchcock

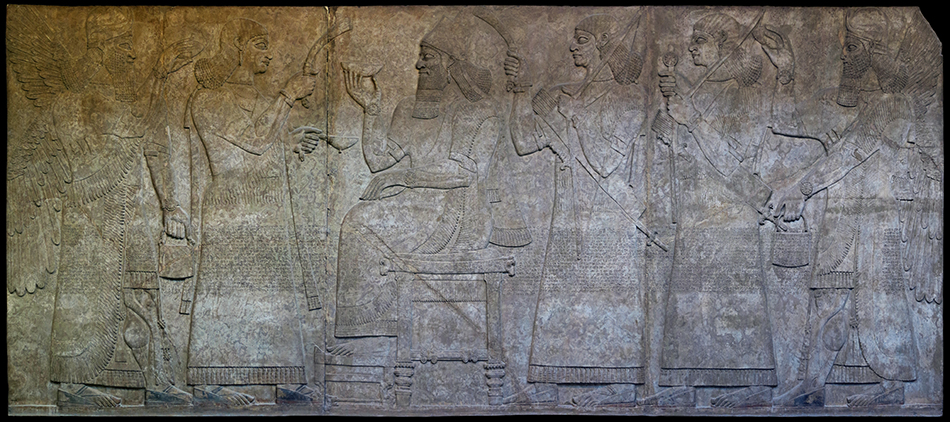

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Wall panel; gypsum alabaster relief from the North West Palace of Nimrud.

King Ashurnasirpal appears twice, dressed in ritual robes and holding the mace symbolising authority. In front of him there is a Sacred Tree, possibly symbolising life, and he makes a gesture of worship to a god in a winged disc. The god, who may be the sun god Shamash, has a ring in one hand; this is an ancient Mesopotamian symbol of god-given kingship.

There are protective spirits on either side behind the king. This symmetrical scene, heavy with symbolism, was placed behind the royal throne. There was another opposite the main door of the throne room, and similar scenes occupied prominent positions in other Assyrian palaces; they were also embroidered on the royal clothes. Traces of colour pigment were noted on the sandals at the time of excavation, i.e. red soles and black uppers.

Circa 883 BC - 859 BC.

Height 195 centimetres (in total), width in total 433 cm.

There was another of these opposite the main door of throne room and in other palaces and the scene would have been represented on royal clothes.

In set with 1849,1222.4-5

In set with 1850,1228.24-26

Found by Layard, May 1846; packed into five cases on a raft despatched from Nimrud April 1847; three cases were shipped on the Indian Navy sloop 'Clive' June 1848, reaching Bombay in October that year and then brought to England on H.M.S. Meeanee in August 1849; the two remaining cases were shipped direct to England on the 'Apprentice' in August 1848, arriving January 1849.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, pigmented, Nimrud, BM/Big number 124531

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

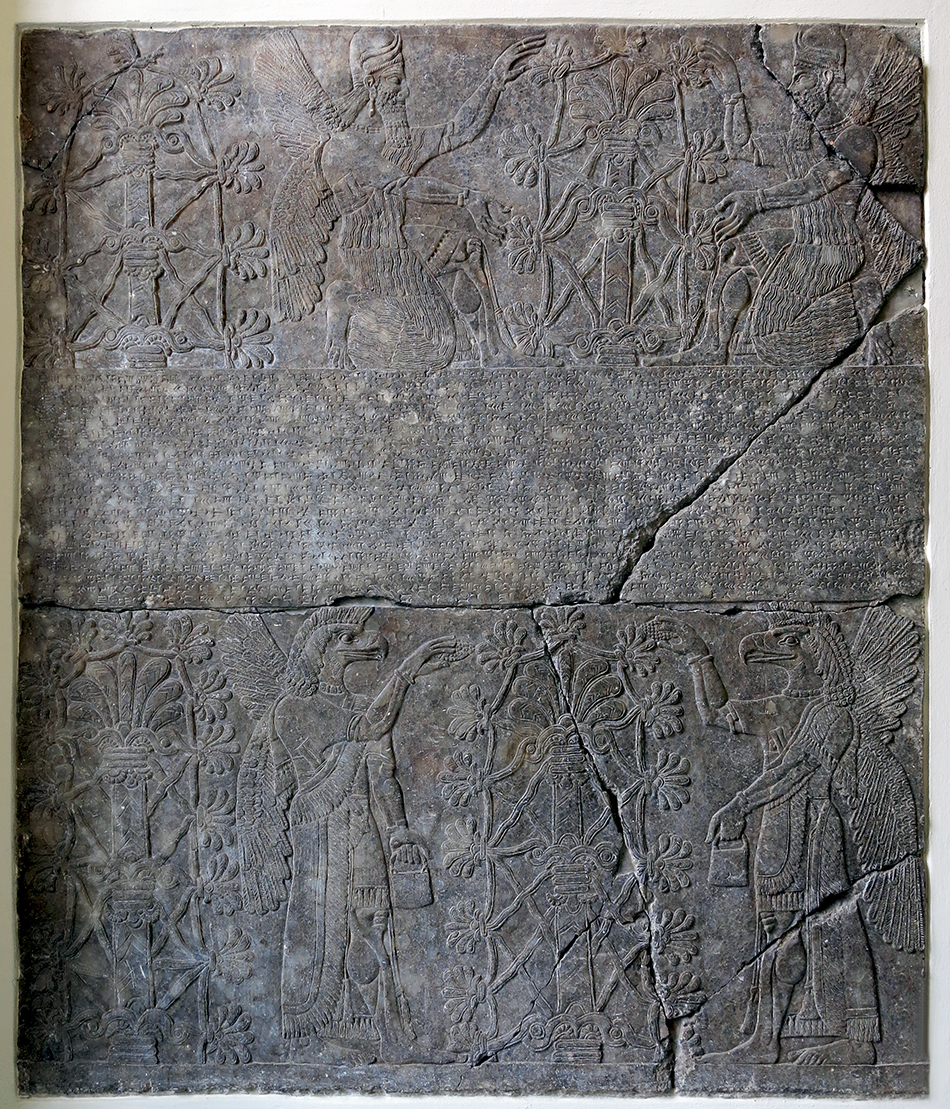

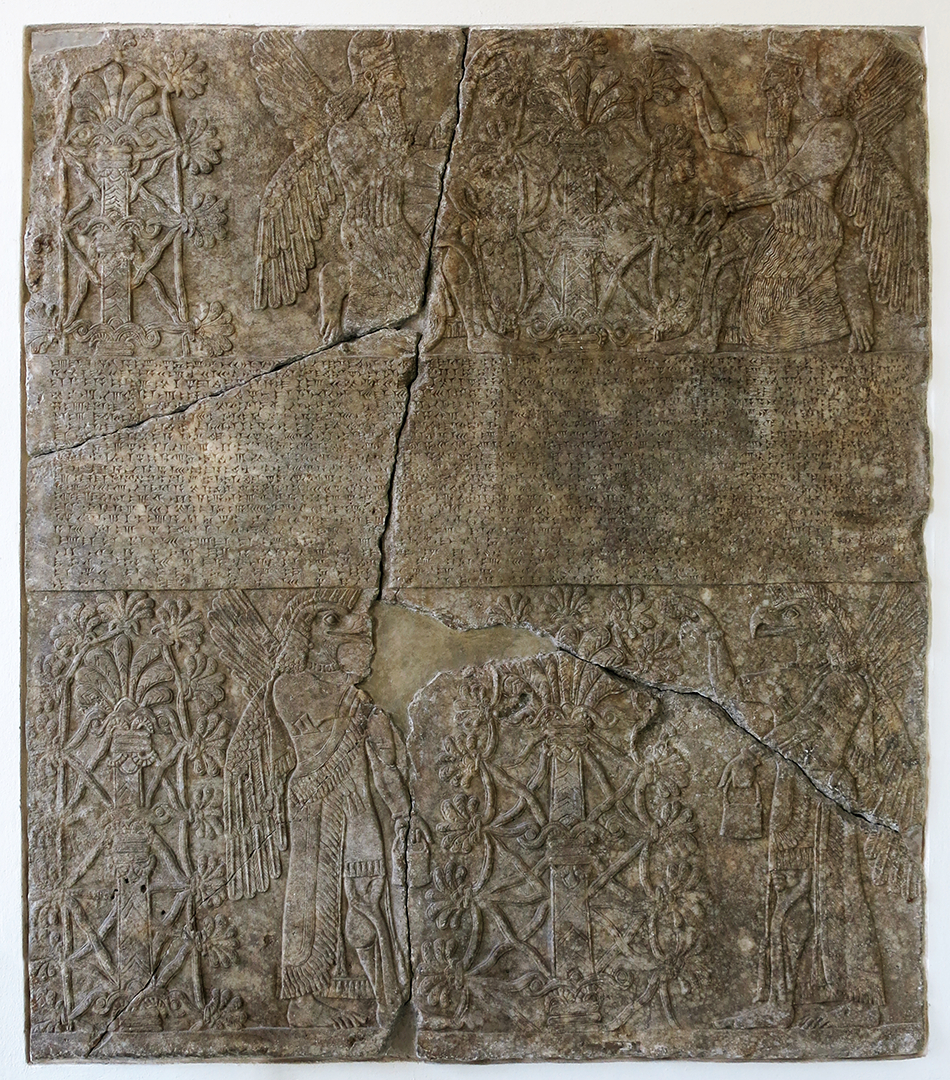

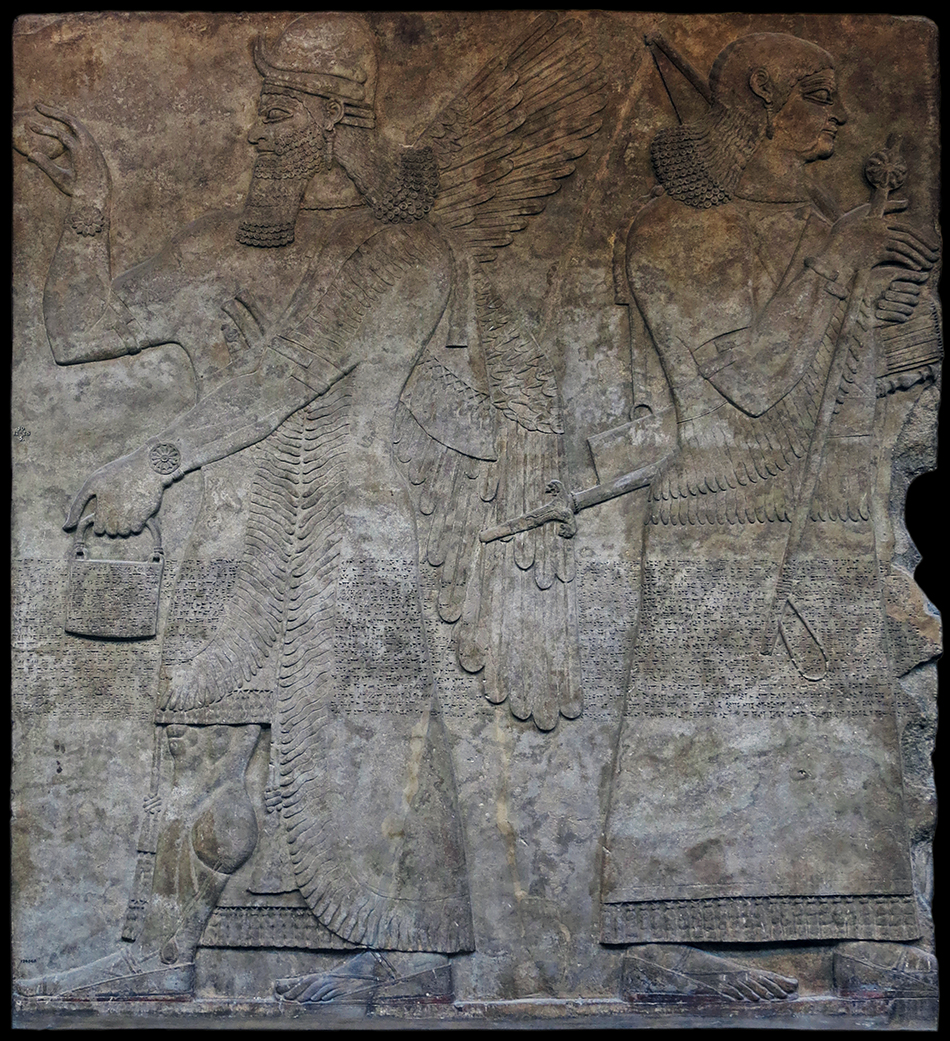

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Wall panel; gypsum alabaster relief from the North West Palace of Nimrud.

This is a three-part representation with genii in front of a palmette tree ( a palmette is

an ornament of radiating petals that resemble the leaflets of a palm - Don )

and the standard inscription.

Height 2300 mm, width 1980 mm, depth 110 mm, weight 1430 kg.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, Nimrud, VA 00949

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Pergamon Museum, Berlin, www.smb-digital.de/

Permalink: id.smb.museum/object/1743976/dreiteilige-darstellung-mit-genien-vor-einem-palmettenbaum-und-standardinschrift

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Bull Hunt wall panel / orthostat.

Gypsum alabaster relief from the North West Palace of Nimrud.

Height 790 mm, width 660 mm, depth 110 mm, weight 160 kg.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, Nimrud, VA 00962

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Pergamon Museum, Berlin, www.smb-digital.de/

Permalink: id.smb.museum/object/1743974/orthostat-mit-darstellung-einer-stierjagd

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Relief of a prisoner of war.

Gypsum alabaster relief from the North West Palace of Nimrud.

Height 1150 mm, width 710 mm, depth 110 mm, weight 250 kg.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, Nimrud, VA 08747

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Pergamon Museum, Berlin, www.smb-digital.de/

Permalink: id.smb.museum/object/1743981/relief-eines-unterworfenen

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Wall panel; gypsum alabaster relief from the North West Palace Room I of Nimrud.

This is a three-part representation with genii in front of a palmette tree ( a palmette is

an ornament of radiating petals that resemble the leaflets of a palm - Don )

and the standard inscription.

Height 2250 mm, width 2030 mm, depth 110 mm, weight 1430 kg.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, Nimrud, VA 00950

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Pergamon Museum, Berlin, www.smb-digital.de/

Permalink: id.smb.museum/object/1743991/dreiteilige-darstellung-mit-genien-vor-einem-palmettenbaum-und-standardinschrift

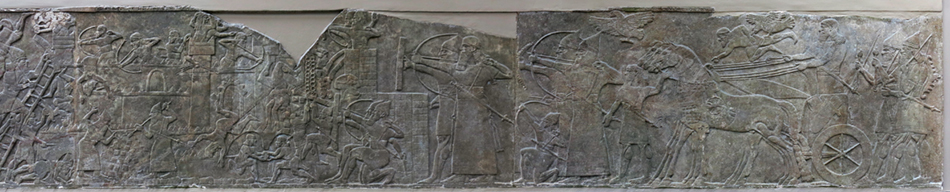

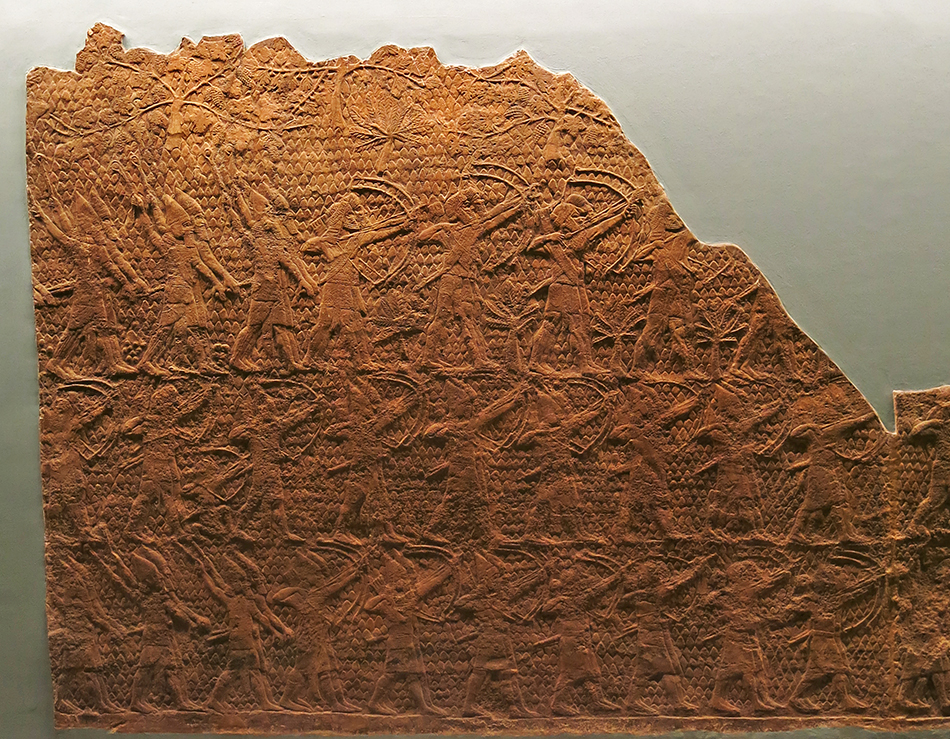

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

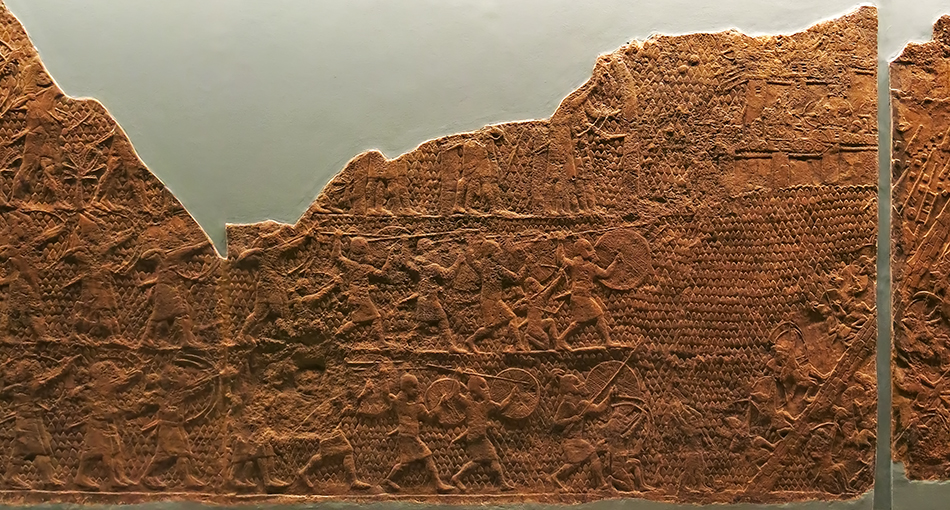

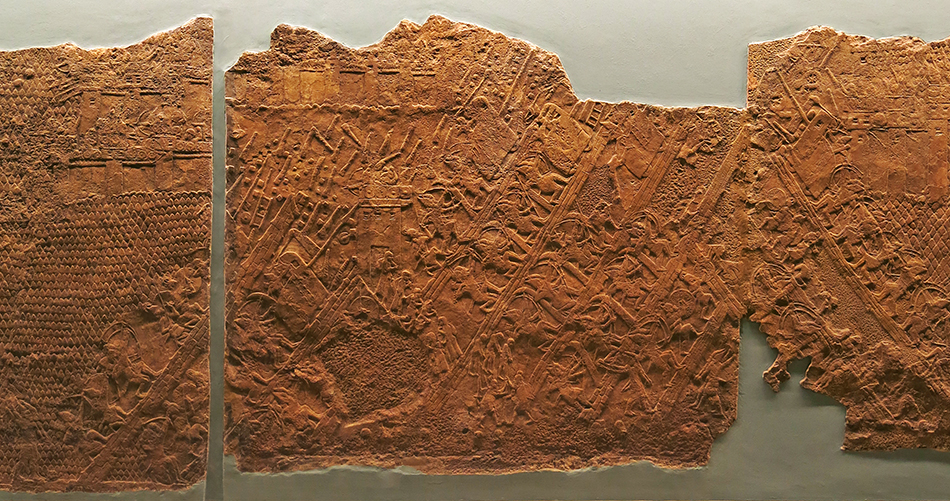

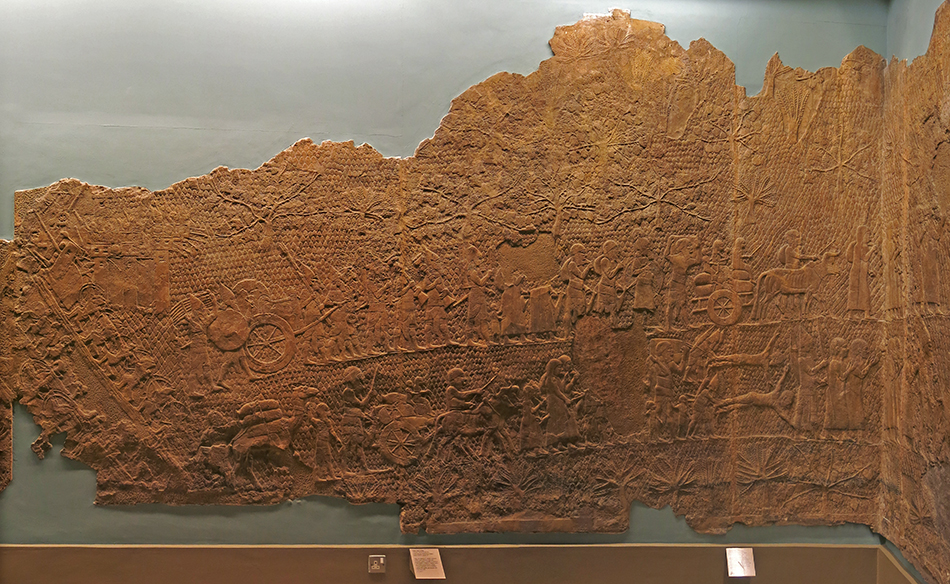

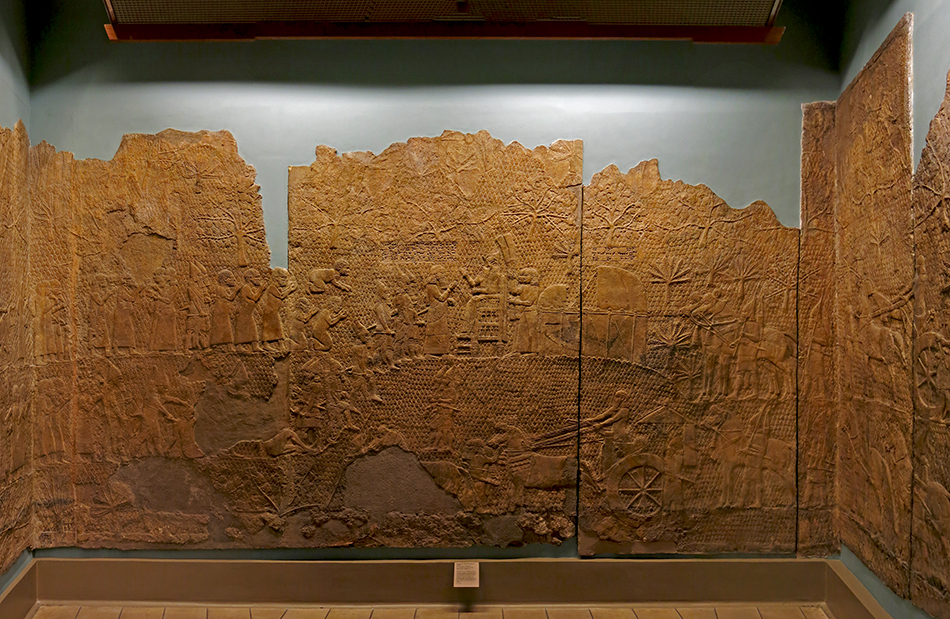

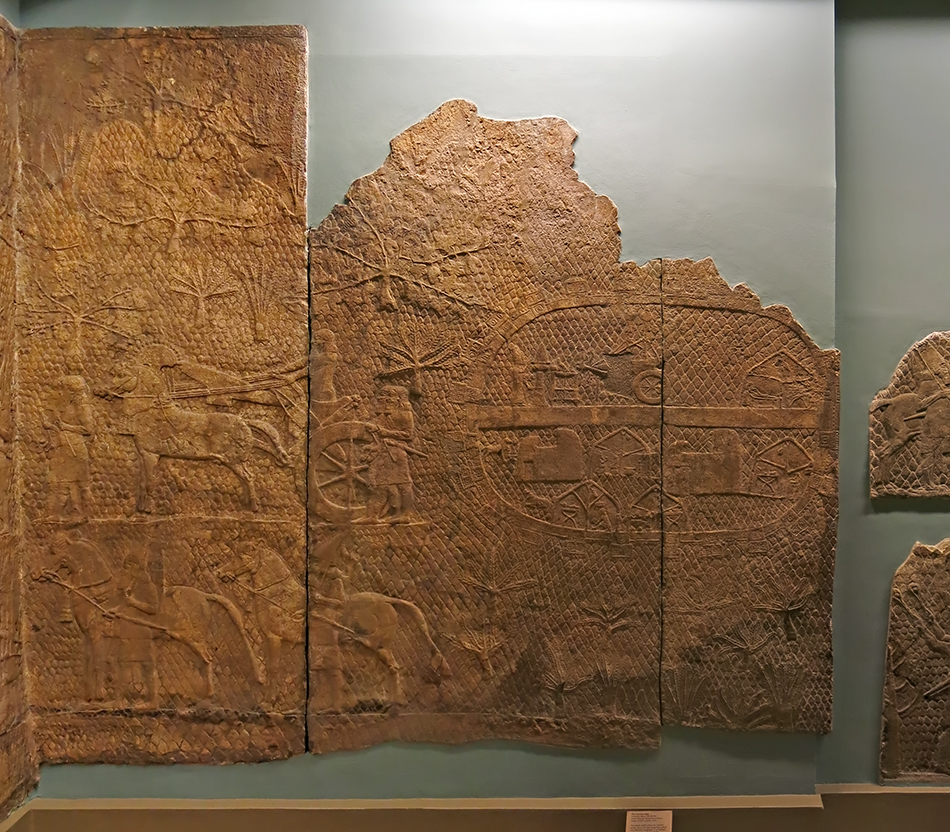

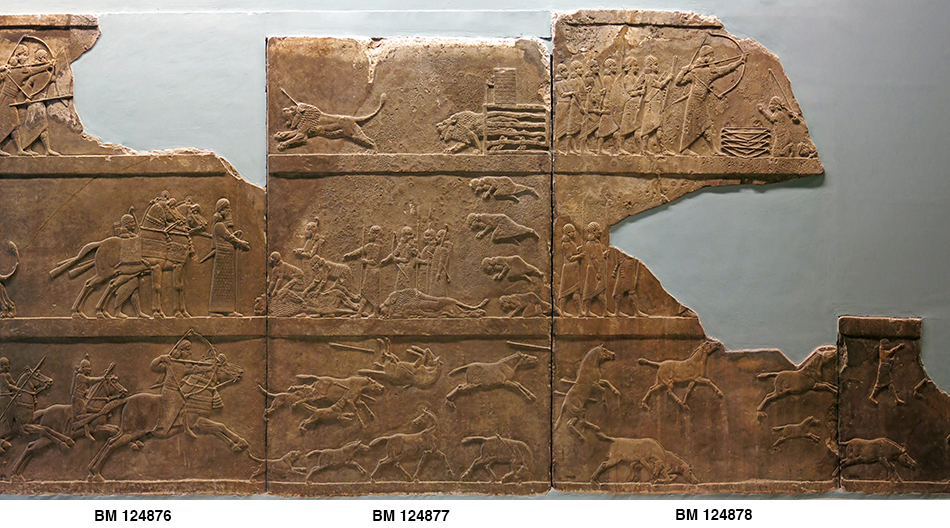

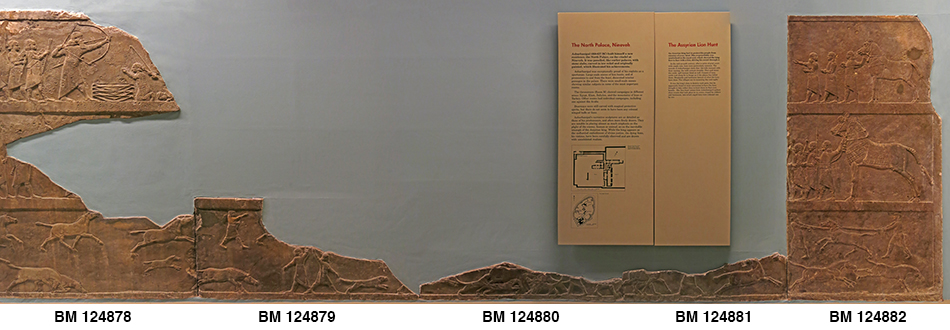

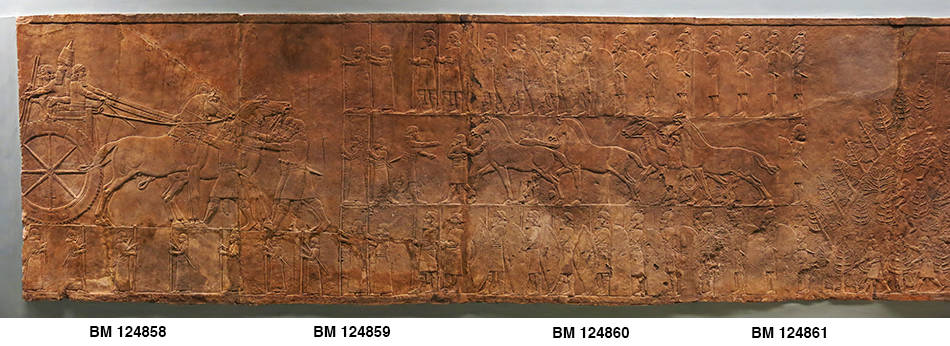

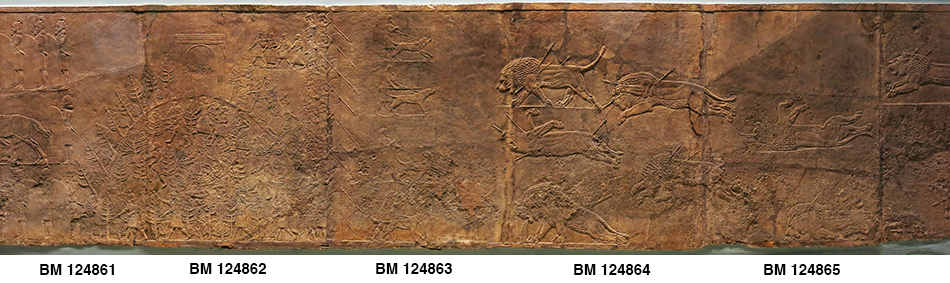

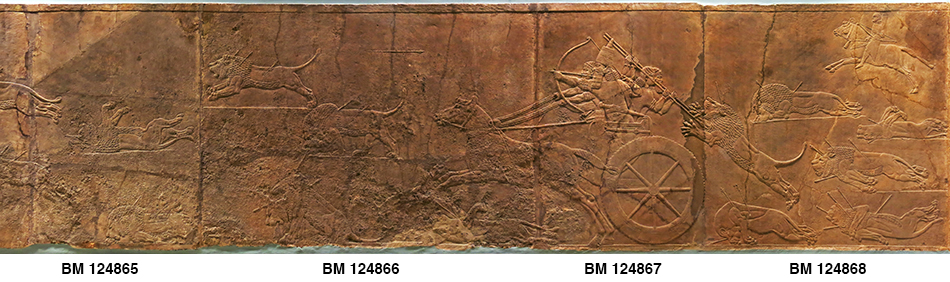

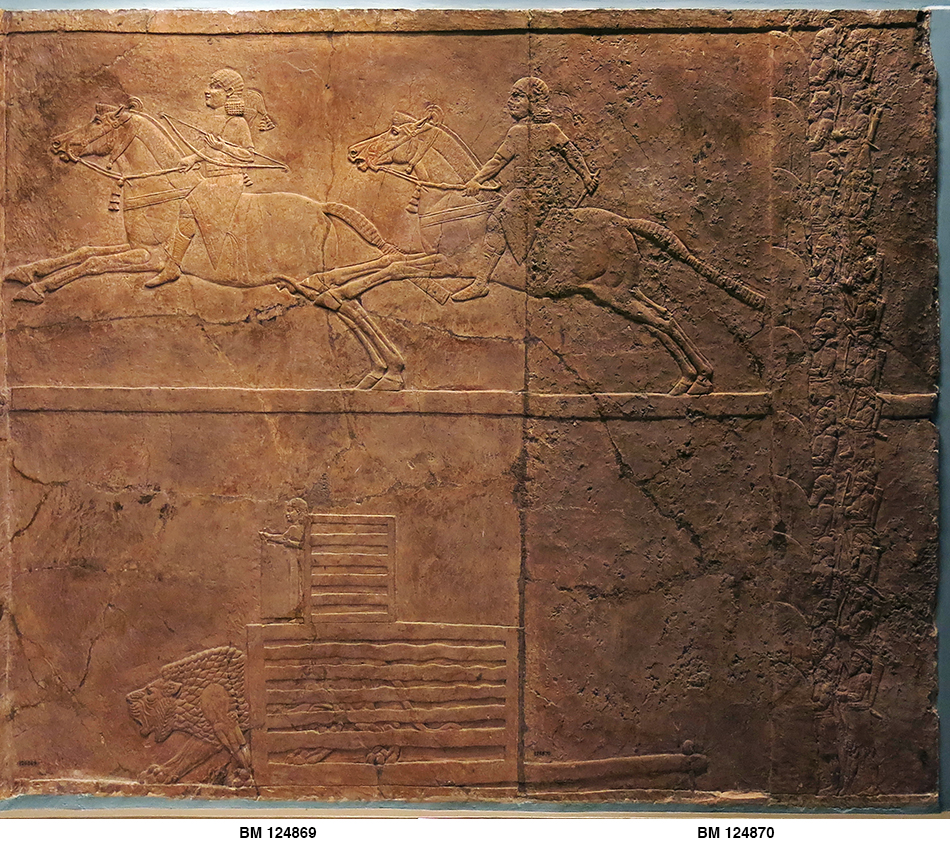

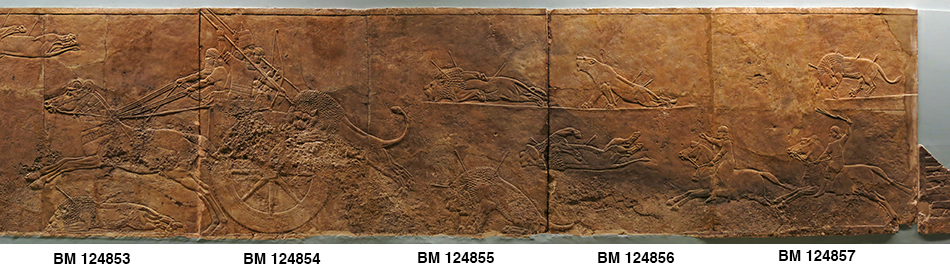

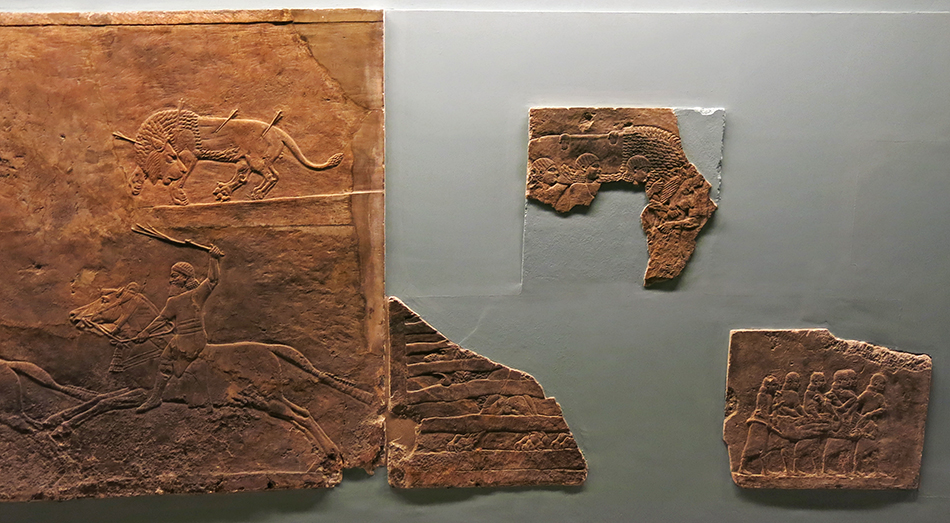

Relief depicting a lion hunt, North West Palace, Nimrud.

This Lion Hunt Relief came from the western wing of Northwest Palace of the Royal Residence of King Ashurbanipal in Nimrud, present-day Iraq. The relief shows the king, standing on a light hunting chariot, which is guided by a charioteer and pulled by three horses. Three arrows have hit the lion. The King once again aims an arrow at the lion. The lion has turned its head back and seems to roar at its attacker in pain.

The royal lion hunt is a symbol of the King overcoming the dangers and challenges to the Assyrian state by its ruler.

Particularly noteworthy is in the initially coloured bas-relief of detail, such as in hunting chariots and weapons, as well as in the richly decorated horses with their teeth.

This section of the relief is only the lower part of a three-walled wall relief, the total height of which was about 2300 mm.

While the upper register with another narrative relief is lost, only a few remnants of two lines of cuneiform have been preserved from the middle register, which bore the king’s standard inscription.

An almost identical representation, now in the British Museum in London, shows the bow-shooting king, who has just killed a male lion.

Nimrud has been one of the primary sources of Assyrian sculpture, including the famous palace reliefs.

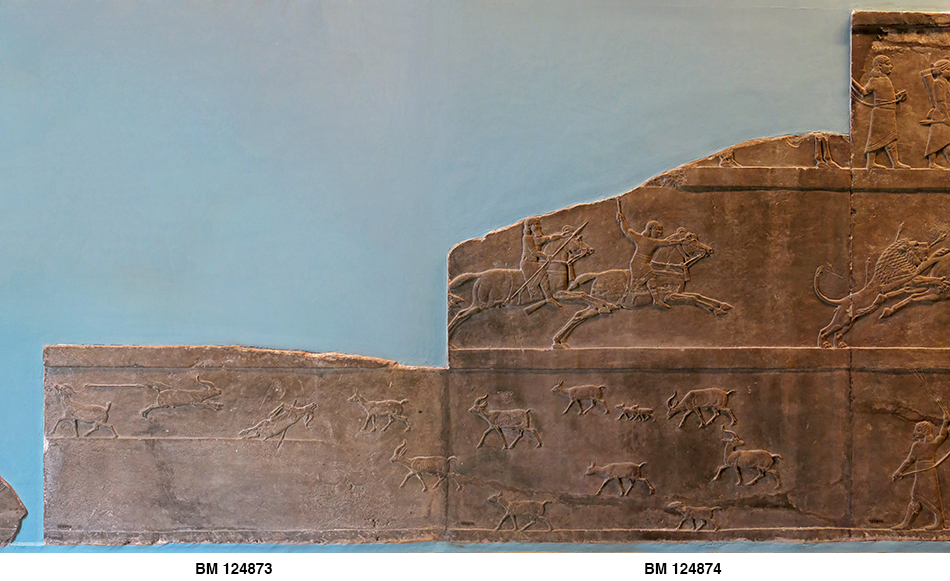

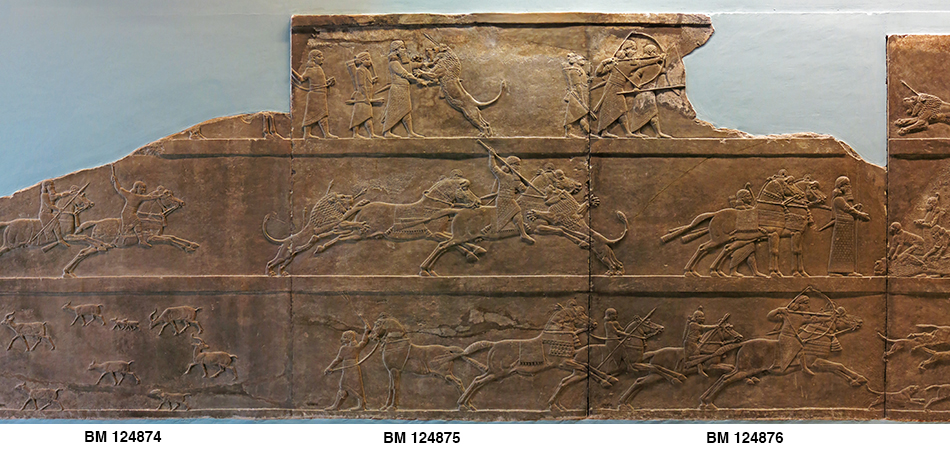

A series of the distinctive Assyrian shallow reliefs were removed from the palaces, and sections are now found in several museums, in particular, the British Museum and the Pergamon Museums. These show scenes of hunting, warfare, ritual, and processions. There are about two dozen sets of scenes of lion hunting in surviving Assyrian palace reliefs.

Neo-Assyrian palaces were very extensively decorated with such reliefs, carved in shallow reliefs on slabs that are mostly of gypsum alabaster, which was plentiful in northern Iraq.

Other animals were also shown being hunted, and the main subject for narrative reliefs was the war campaigns of the king who built the palace. Other reliefs showed the king, his court, and 'winged genie' and lamassu protective minor deities.

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located 30 kilometres (20 mi) south of the city of Mosul, in the Nineveh plains in Upper Mesopotamia.

It was a major Assyrian city between about 1350 BC and 610 BC. The city is located in strategic position north of the point that the river Tigris meets its tributary, the Great Zab.

In the mid 19th century, biblical archaeologists proposed the Biblical name of Kalhu (Calah), based on a description in Genesis 10. The city gained fame when king Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC) made it his capital at the expense of Assur.

He built a large palace and temples in the city, which fell into disrepair during the Bronze Age Collapse of the mid-11th to mid-10th centuries BC.

Archaeological excavations at the site began in 1845, and many vital artifacts were discovered, with most being moved to museums in Iraq and abroad. Historical artefacts from Nimrud can now be found in over 76 museums worldwide, including 36 in the United States and 13 in the United Kingdom. In 2015, the terrorist organization, the Islāmic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), destroyed much of the site. The excavated remains were damaged because of its Assyrian history.

The relief from the western wing of the so-called Northwest Palace of the royal residence in Kalchu (today Nimrud/Iraq) is only the lower part of a three-register wall relief, the total height of which was approx. 2300 mm. The king is depicted standing on a light hunting chariot, which is led by a driver and drawn by three horses.

Height 970 mm, width 1830 mm, depth 110 mm, weight 555 kg.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, Nimrud, VA 00959

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Pergamon Museum, Berlin, www.smb-digital.de/

Permalink: id.smb.museum/object/1743971/relief-mit-darstellung-einer-l%C3%B6wenjagd

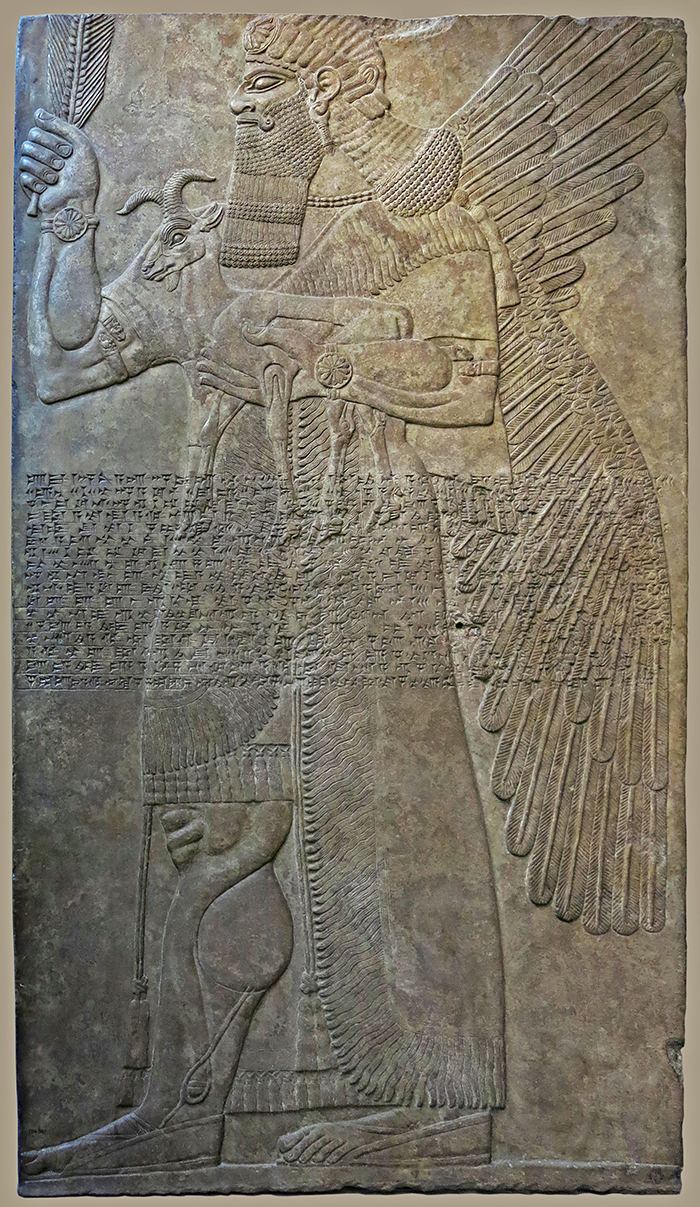

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

Wall panel; gypsum alabaster relief from the North West Palace of Nimrud.

Circa 883 BC - 859 BC.

Gypsum alabaster wall panel depicting a protective spirit in relief: this figure, a man with wings like an angel, is a protective spirit, probably an 'apkallu'. He carries a goat and a giant ear of corn ( i.e. wheat or barley - Don ), possibly symbolic of fertility though their precise significance is uncertain.

He wears a kilt with long tassels hanging from it, indicating his semi-divine status, and a fringed robe, embroidered with clusters of dates, which is drawn round the body and thrown over his shoulder, leaving the right leg exposed. There are sandals on his feet. A bead necklace round his neck is held in position by a tassel at the back. His armlets have animal-head terminals, and there are rosettes on his wristlets and on his diadem.

He has the magnificent curled moustache and long curled beard and hair typical of ninth-century figures. The musculature of his leg is exaggeratedly drawn, with a prominent vein encircling his ankle.

Across his body runs the standard inscription. This was incised after the carving of the figure was complete, and it cuts through some of the fine details of decoration on the dress.

Height 224 cm, width 127 cm, thickness 12 cm.

This figure was probably one of a pair which guarded an entrance into the private quarters of the king. It was previously described on a label as from Room Z rather than T.

Shipped by the excavator, Sir Austen Henry Layard, on the 'Apprentice'; arrived January 1849.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, pigmented, Nimrud, BM/Big number 124561

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card with the display at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

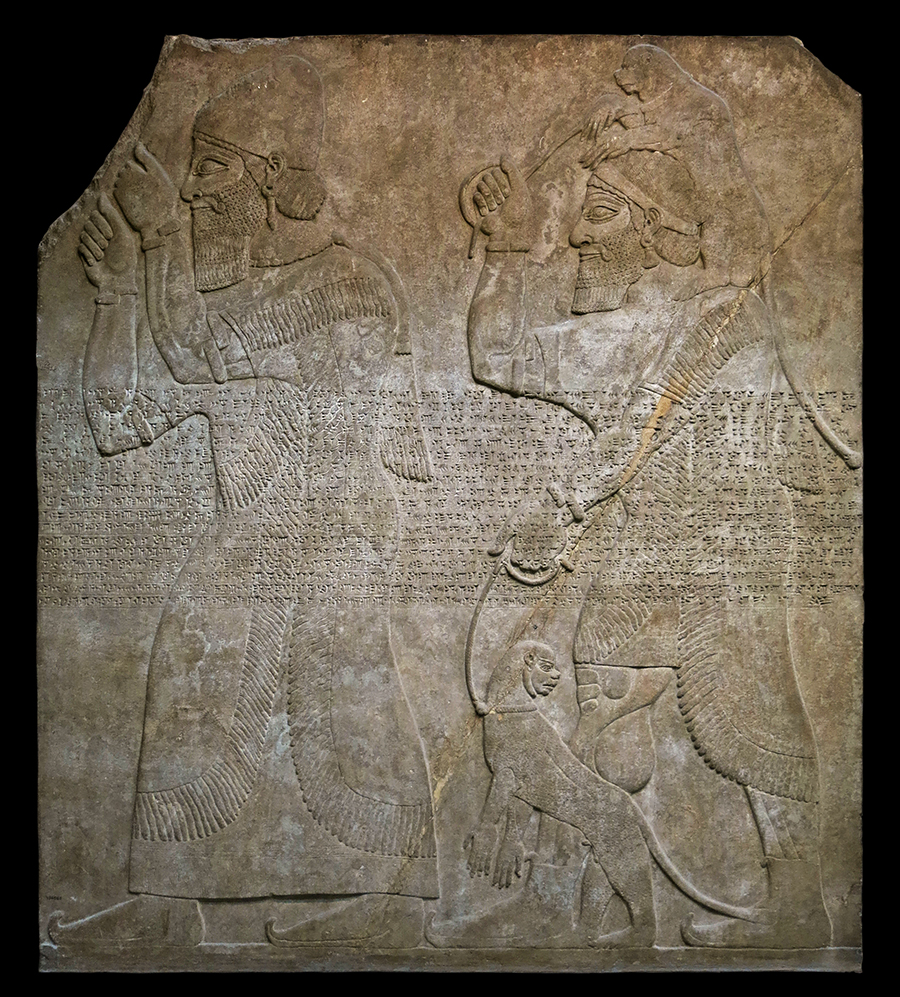

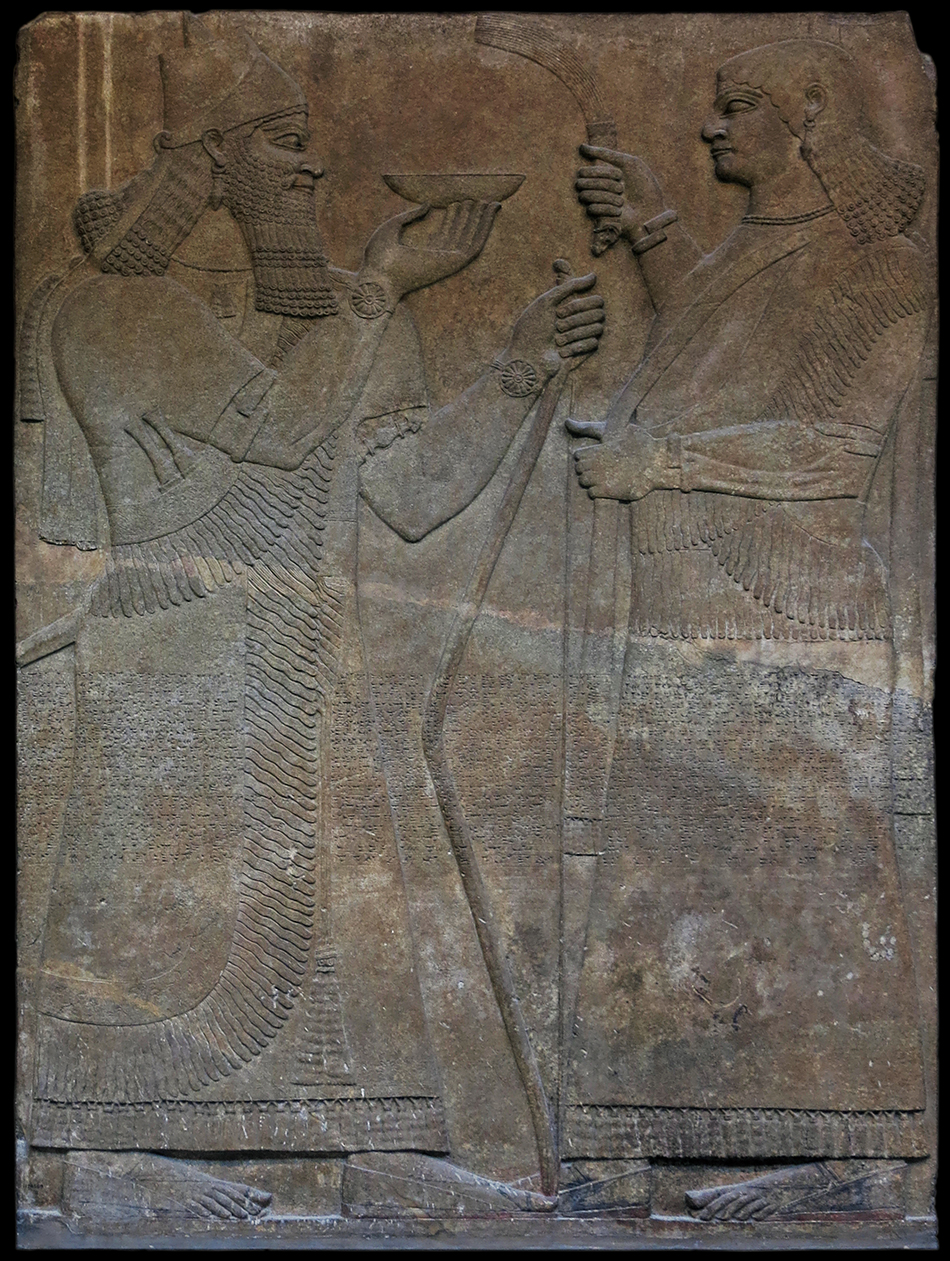

Reign of King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC)

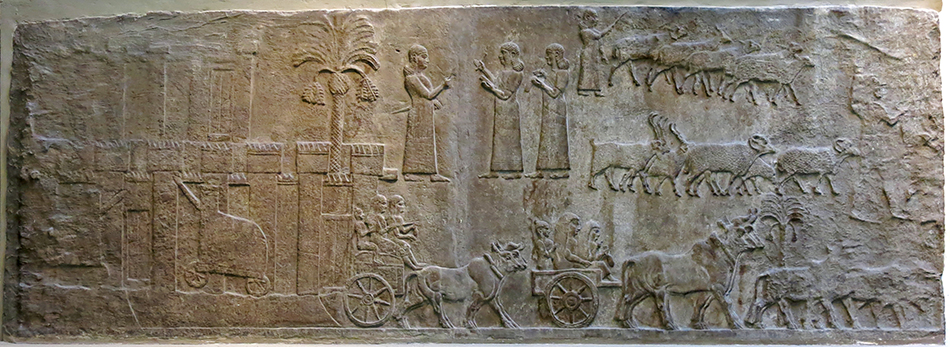

Tribute Bearers

Circa 883 BC - 859 BC.

Gypsum wall panel relief from the North West Palace of Nimrud, carved and showing tribute bearers. One has a North West Syrian type turban and raises clenched hands in token of submission; the second may be Phoenician and brings a pair of apes.

There is an inscription written in cuneiform script with partial white infilling in some of the signs. The panel originally had traces of black paint at the top.

Height 263 cm, width 259 cm.

This panel was part of the façade of the throne room. Layard (1849, 'Nineveh and its Remains', vol. I, p. 118) refers to how at the time of discovery there were extensive traces of black pigment covering the face of the man with the monkeys, and he speculated that this was either from a deliberate attempt to depict a negro or that the paint had washed down from the man's hair. No traces of this are now visible to the naked eye (2008).

Layard refers to the survival at the time of excavation of pigment on selective portions of other sculptures at Nimrud, specifically on the hair, beards, eyes and sandals of some sculptures and the red-painted tongue of an eagle-headed genie (ibid., pp. 71-72, 126). The white infilling in the inscription on this particular scuplture may also be ancient and resembles a feature noted on Persepolitan (the capital of ancient Persia) inscriptions.

Catalog: Gypsum alabaster, pigmented, Nimrud, BM/Big number 124562

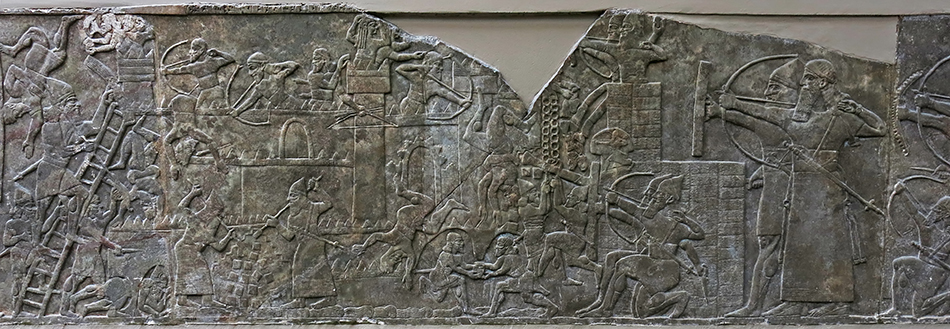

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015