Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

Mesolithic sites in northern Europe

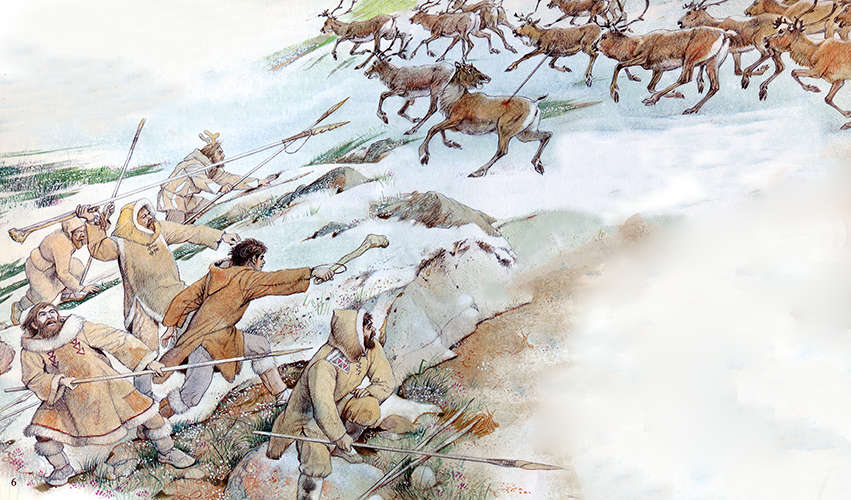

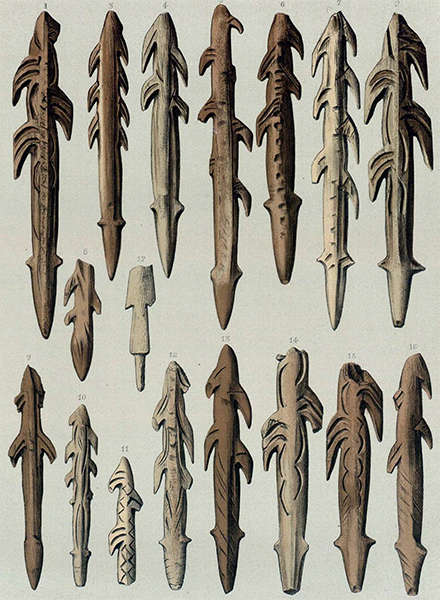

When hunting reindeer, the band cooperated closely. Their long, thin and flexible darts were launched from a spear thrower or atlatl, which was a lever which allowed the hunters to get a much greater range and force for their shafts. The darts were armed with both flint blades, especially the characteristic shouldered or tanged points of the Havelte type, and with barbed antler harpoons.

Reindeer antler is a strong, tough material, much stronger than, for example, red deer antler, and could be made into harpoon heads which were quite capable of bringing down an adult reindeer with one shot, a good cast blasting a hole through the shoulder blade of the reindeer, and immobilising the joint. This allowed the hunters to close with the animal, and finish it off.

The hunters aimed for the lifeline, a line connecting the heart and the mouth, and any spear which hit in that area would likely drop the reindeer in its tracks.

The animal would be dressed on the spot, with the abdominal cavity cleaned out and left for scavengers, and only the high value parts of the reindeer carried back to camp, with the load distributed amongst the hunting band.

We think of harpoons (that is, barbed bone or antler spear points) as being used for fish and large sea animals such as seals and whales, but they were first developed for reindeer hunting, and only later adapted for use with fish and marine mammals.

Photo and text: Adapted from Caselli (1985)

Additional text: Bibby (1956)

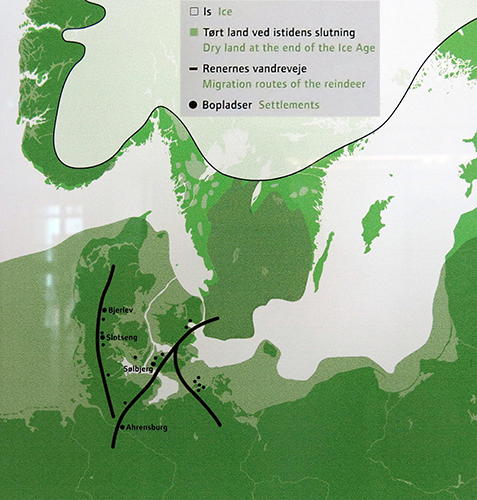

Northern Europe about 17 000 BP. The ice-cap has drawn back from all but the northern fringe of Germany, from the greater part of Denmark, and from the coasts of Norway. The sea, swollen by the melting ice, is creeping across the North Sea Plain to meet the Reindeer Hunters, whose summer camps at Meiendorf and Stellmoor may well have been less than 30 miles from the eternal ice.

Photo and text: Bibby (1956)

The darts and spear thrower were carefully made. The head of the spear often had a harpoon carved from reindeer antler instead of a flint point, with the harpoon mounted in such a way that it parted company with the shaft when the reindeer was struck, and there was less chance of either being broken.

The spear thrower gave much greater speed and distance to the spear because of the extra leverage gained.

A broken point or harpoon could be easily replaced in the field, but a dart was a big investment of time and effort, and was difficult to replace when there were few trees around, as was the case in the summer grazing grounds in the tundra.

One big advantage given by the development of the bow and arrow was that the shafts of the arrows were much shorter and thinner than darts, and very much easier to replace.

In addition, instead of just two or three unwieldy spears carried in the hand, dozens of arrows could be carried in a quiver on the back of the hunter, and the bow and arrow combination allowed the hunter to move into position quickly and easily, and to fire multiple shafts in a few seconds.

Photo: Caselli (1985)

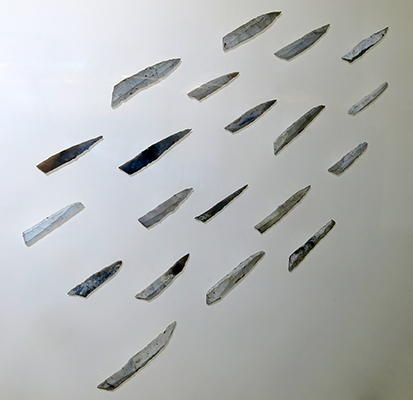

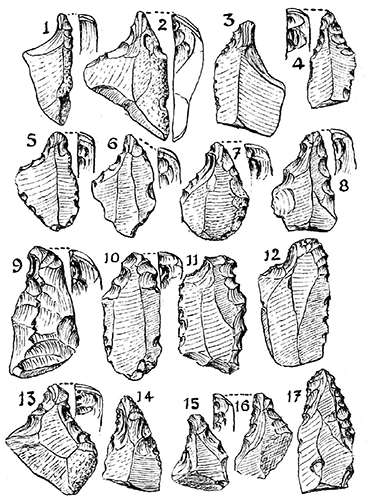

This is by far the most beautiful display of flint tools I have ever seen. It is a work of art in itself, and a tribute to the staff of the museum.

The Cro-Magnons hunted with light spears thrown with atlatls, propulseurs. Bows and arrows only came later - when is uncertain - but at the end of the Ice Age we find arrow shafts with notches for bowstrings in the Ahrensburg Culture, ca 11 000 BP.

Throwing spears and arrows had sharp flint points shaped according to changing fashions; the soil still contains relics of 10 000 years of hunting - the small arrowheads of flint that made the hunters' weapons so fatally effective.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Flint points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Microblades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Trapezoidal microblades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Trapezoidal microblades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Flint points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Flint points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Trapezoidal microblades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Micriblades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Flint points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Trapezoidal microblades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Flint points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Flint point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered point with a very distinct 'tang'.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Flint points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Microliths. These are remarkably similar in shape to Australian 'Adelaide' points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Trapezoid microliths.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Microliths.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Trapezoid microliths.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Trapezoid microlith.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Shouldered point.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source : Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Towards the end of the Ice Age birch forests grew up. The last refuge of the now-extinct giant deer was the young forest landscape - ideal too for elk (moose) which ate the aquatic plants in the extensive wetlands. Hunters also gathered at the lakes, using harpoons to kill animals trying to swim away. After the quarry had been cut up the bones were sunk in the lake as hunting sacrifices. In a lake at Koelbjerg on Funen a woman drowned 10 000 years ago. She is the oldest known Dane.

This skull of the woman from Koelbjerg on Funen is typically Cro-Magnon. 10 500 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Facsimile, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

A wounded elk (moose) sank exhausted to the bottom of a lake at Tåderup on Falster 8700 years ago. In 1922 the skeleton was found in a peat bog. Among the bones was a broken bone point that may have been used in the hunt. Later a harpoon was found in the same peat bog.

Several kinds of tools and weapons were made from the large animals' antlers and slender bones. The hunting was so intensive that the species was wiped out in Zealand ca 8500 years ago. However the elk still played an important role in the hunters; mythology. Tooth beads, and tools of elk antler and bone were valuable barter objects.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark, on loan from Zoologisk Museum.

Bone harpoon, found near the elk skeleton. Tåderup, Falster, ca 8700 BP.

Bone point, broken, found among the elk's remains. Tåderup, Falster, ca 8700 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Apparently facsimiles, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark, on loan from Lolland-Falsters Stiftsmuseum.

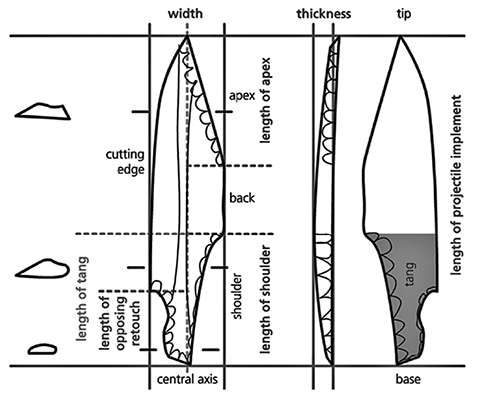

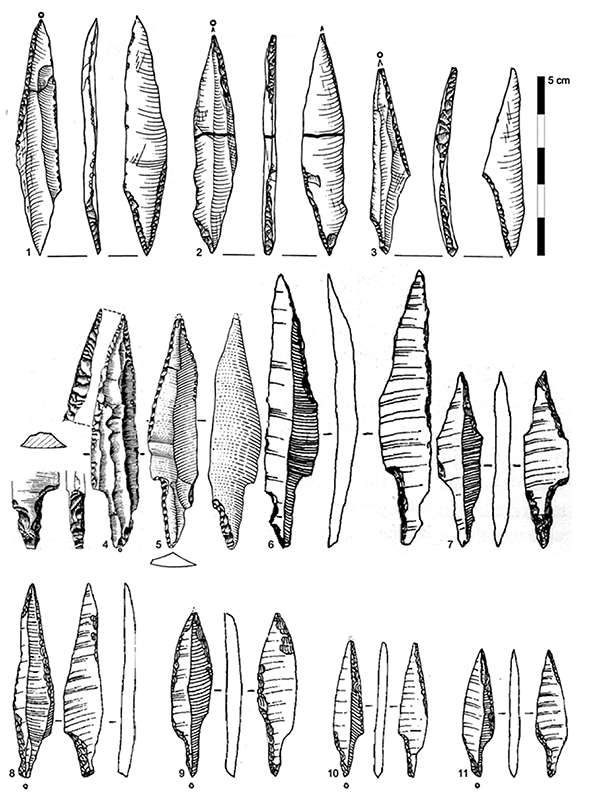

Kerfspitsen van het type Havelte - Shouldered or Tanged points of the Havelte type.

Idealised Havelte point with metric terms indicated.

The tang is here defined as the lower, articulated part of the

point and its length is consequently defined as the maximum length of the lower retouches.

Photo: Drawn by S.B. Grimm, in Grimm et al. (2012)

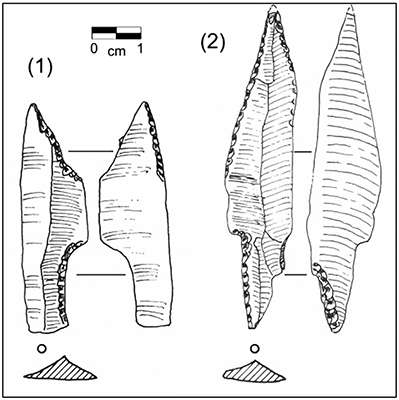

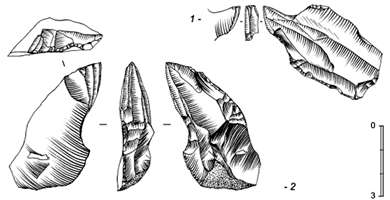

1. 'Classic' Hamburgian shouldered point.

2. Havelte shouldered point.

Photo and text: Riede (2010)

Havelte points have been dated to the late Hamburgian, and were most probably attached to arrows rather than darts ( Niekus et al., 2012 ).

Darts, arrows, spear throwers and bows would all have been most easily fabricated during winter in the margins of the forests at the far, southern end of the reindeer migration paths, where the forests began.

Wood suitable for arrow and spear or dart shafts would have been very difficult to obtain in the summer grazing areas in the tundra not very far from the ice sheets. Some small trees would have grown in sheltered positions, but the reindeer hunters would have brought most of their weapons with them, although flint for replacement points and other tools may have been available in the glacial till.

Photo: Instituut voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium (Zellik) (1994)

Artist: © Benoit Clarys

Examples of Havelte tanged points from Oldeholtwolde (nos. 1-3), Havelte-Holtingerzand (no. 4), Dörgener Moor (no. 5), Slotseng c

(nos. 6 & 7) and Jels 2 (nos. 8-11)

The actual use of Havelte tanged points as projectile implements was indicated by impact patterns and traces on certain specimens from different Havelte Group sites.

Whether Havelte tanged points armed spears or arrows remains a matter of debate. However, considering the weight of these examples, Havelte tanged points were more likely to be arrow points than spear points.

At the Danish Havelte Group site Slotseng a detailed botanical analysis was conducted on samples from the kettle hole where a horizon with humanly modified reindeer remains was found. This horizon was correlated with a maximum of pollen of buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides), which is a typical pioneer plant. Comparable to the pollen, the macrofossils indicated a cold and open landscape with Dryas octopetala and first indicators of dwarf birch Betula nana as well as some remains of willow, Salix sp. However, the vegetation in this central part of Denmark must be described as sparse, reflecting an environment comparable to an arctic tundra at the time the reindeer were hunted there. The faunal remains from the kettle hole in Slotseng were comprised of bones and antlers of some 12 reindeer and some 14C dated samples attributed the assemblage to the Early Late Glacial Interstadial, with a weighted average date of ~14 000 BP.

According to the seasonal indications, the hunting occurred most likely around early November. Whether these remains originated from a single hunting event or recurrent episodes of seasonal hunts cannot be finally decided from the archaeological record. In the vicinity two concentrations of Havelte Group material (Slotseng a and c) as well as two further concentrations attributed to the Curve Backed Point (CBP) Groups were found. No other faunal assemblage is associated with a Havelte Group site and, consequently, little can be assumed about the Havelte Group subsistence strategies in general.

Photo and text: Grimm et al. (2012)

'Classic' Hamburgian shouldered point from Robin Hood Cave, Britain, Cat. +.7939

The point lacks a proximal end due to an ancient break. There is a tiny scalar retouch on the oblique left edge below the distal end which accentuates the point. There is an abrupt, scalar retouch extending from the distal end to above the midline which forms a shoulder on the left edge. The piece is fresh, with slight patination.

Findspot: Robin Hood Cave, Creswell Crags.

Length: 46.4 millimetres, Width: 16.4 millimetres, Thickness: 3.7 millimetres, Weight: 3 grams

Donated by: Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks

Excavated by: Rev John Magens Mello

Acquisition date: 1883

Photo and text: http://www.britishmuseum.org/

Harpoons of the Hamburgian and Ahrensburgian culture, made in reindeer antler.

1. Meiendorf

2. Stellmoor

3. Skaftelev

Photo and text: Clark (1966)

Harpoons in reindeer antler, barbed on both sides. Grotte de Lorthet (Hautes-Pyrénées).

Although these harpoons were found a long distance south from the Hamburgian culture sites, and are many thousands of years younger, they serve to show the effort that was put into making a simple weapon into a work of art.

Photo and text: Piette (1907)

Basale fragmenten kerfspitsen - Basal fragments of kerfspits, or shouldered points

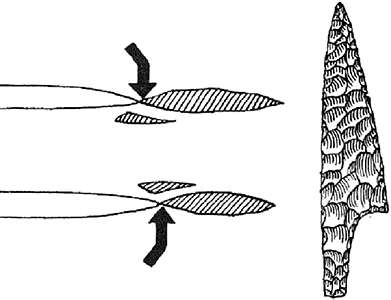

Two views of a Pointe à cran, or shouldered point.

Date: between 22 000 and 17 000 BP, Upper Paleolithic (Solutrean)

Dimensions: 42 x 11 x 4 mm (1.7 × 0.4 × 0.2 in) - 1.3g

Current location: Museum of Toulouse

Accession number: MHNT.PRE.2009.0.226.2

Place of discovery: Grotte de L’église, Saint-Martin near Excideuil, Dordogne, France – Former collection of J. & P. Parrot.

Photo: Didier Descouens, 31 December 2010

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

End-on views of pressure-flaking show how force is applied to the tool edge itself to make the shoulder of a shouldered point. Controlled fracturing with this method results in finer flakes and finer tools, like the leaf point at right.

Photo and text: Howell (1965), drawings by Lowell Hess.

Burins and scrapers and knives were essential tools in the life of the reindeer hunters.

Southern Europe below the Scandinavian Peninsula is fortunate in having vast deposits of limestone and the flint nodules that are often found in them.

Photo: Caselli (1985)

Krombekstekers - Curved tip beaked burins - Parrot Beak Burins

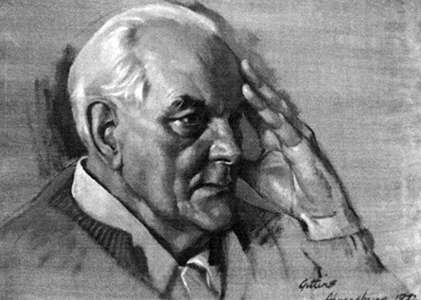

Alfred Rust, a pioneer in the study of the Reindeer Hunters was the first to identify this type of burin in the tool set of what became known as the Hamburg Culture, and lightheartedly wanted to call it the 'Papageienschnabelklingenendhohlkratzerbohrerschraber ' or Parrot-beak-blade-end-groove-scratcher-bore-scraper. He had found it first in the Ahrensburg valley in a meadow called Meiendorf, and recognised it in the collections of Dr Albrecht of Kiel University, who had collected it in a field a little north of Hamburg.

Rust found close by his original ploughed field of Meindorf a site which had been a lake, and into which all manner of detritus had been thrown by the Reindeer Hunters who had camped by its shores. It was what he had been searching for, a stratified site, not a ploughed field which was where all the previous discoveries had been made. When he excavated to the original lake bed, he found what he was looking for - a four foot (120 cm) long reindeer antler, from which a sliver eighteen inches (50 cm) in length had been cut out.

It was at once clear that the purpose of the parrot-beak-groove-scratcher was as a tool to be used to cut out slivers of reindeer antler for fashioning into pins and arrowheads and flint-flakers.

With hard work and the spirit of innovation, Rust used new methods (soil coring, excavation in floodplains with drainage by pumps) to examine the layers of peat around the areas left by the melting of the ice sheet which currently form the Meiendorfer Ahrensburg valley, near Hamburg.

Rust showed (which was denied at the time) that groups of hunter-gatherers frequented the tundra stretching to the foot of the huge glaciers that covered northern Europe during the Ice Age. He found numerous flint tools (awls, scrapers, chisels for working bone and antler, pairs of blades for mounting on a pair of scissors) and carved stone, wood or bone weapons (spears). He also discovered the bones of sacrificed animals, especially deer, found intact except for a large stone which was placed intentionally in the thorax of each animal.

Among his other notable discoveries were an amber plate with a hole and engraved figures (horse, bird, fish), a finely carved and incised stick, and a baton decorated with a large pair of reindeer antlers.

Rust, through his discoveries in the field excavations at Meiendorf, showed that reindeer hunters belonging to the Hamburg culture in the late Palaeolithic were hunting in this region about 15 000 years ago. During a period of warmer climate, about 13 400 years ago, hunters belonging to the Magdalenian culture also lived at the foot of glaciers until a new cold period, 12 700 years ago, after which appeared the reindeer hunting Ahrensburg culture.

Photo: http://www.pkaj.dk/stellmoor_lokaliteten.asp

Text above adapted from Bibby (1956) and Wikipedia

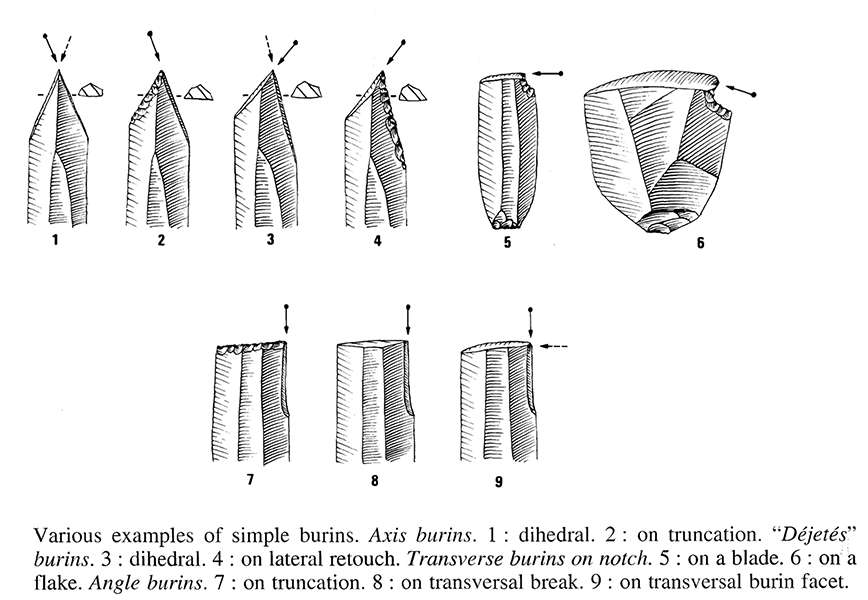

Definitions and knapping techniques for Burins

Readers should note that some Dutch language terms for stone tools have entered the literature as abbreviations, and are used widely in English language journals and books.

One of these is the 'A burin', which comes from the Dutch, Afslag (blade or flake, mostly on transversal break). In fact most burins are made by a transversal break on small blades.

Another is the RA burin, which comes from the Dutch, Retouche - Afslag (Retouch - blade / flake on truncation).

RA burins are made by breaking the end off a blade, blunting it, then using the coup de burin, the burin blow, to detach the burin spall by striking the blunted platform.

The AA burin is also Dutch, Afslag - Afslag (blade / blade or flake / flake, dihedral).

AA burins are thus dihedral burins, or in French, Becs de flûte.

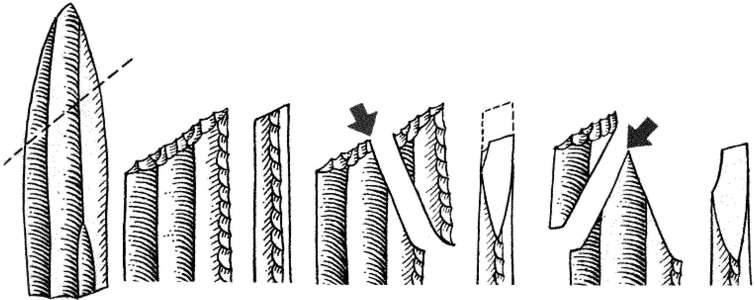

One method of making either:

Blunted Burin - an RA Steker

or

Dihedral Burin - AA Steker - Bec-de-Flûte

Starting with a blade, the toolmaker first snaps the pointed end at an oblique angle (left).

Next, using a wood or antler hammer, they chip the broken end to make a striking platform, then dull one edge (two views, second drawing).

The toolmaker may now make either a single blunted burin, i.e. an RA Steker, or a Dihedral Burin, i.e. an AA Steker, as in the third and fourth drawings.

Photo: Howell (1965), drawings by Lowell Hess.

Text: adapted from Howell (1965)

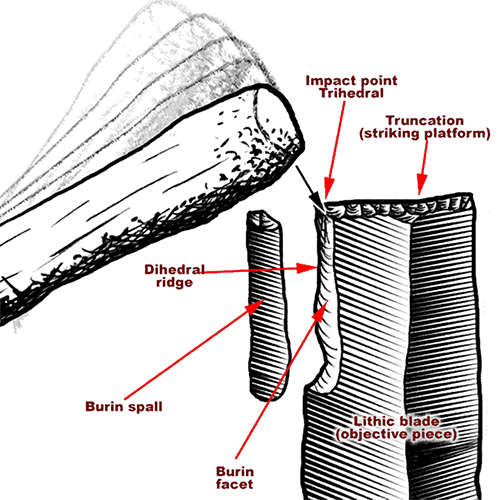

The classic 'Burin Blow' or 'Coup de Burin' is made by first blunting the end of the flake or blade. The blunted edge is then struck with a wooden or antler implement, and a burin spall is detached from the tool. This leaves a cutting edge that shaves razor-like at the bottom and edges of a groove when the burin is drawn edgewise toward the user.

This tool is the blunted burin, or RA Steker. The diagram on the right shows how the burin blow creates the razor sharp edges on each side of a trough or groove, which are so effective in carving materials such as wood, antler and bone.

Photo (left): José-Manuel Benito Álvarez

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license.

Photo (right): Don Hitchcock 2014

Text: Adapted from J.L. Giddings, http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic9-4-229.pdf

Once hunting commenced, a constant supply of hides provided the raw materials for repair of tents, new clothes, plaited ropes, and carrying bags of all kinds. The hides had to be scraped clean of all the membranes and fats and flesh, and then worked to ensure that they stayed pliable and useful.

Huge amounts of time and tools were expended on this task, for it was essential to the continued existence of the reindeer hunters.

The most important flint tools for the reindeer hunters apart from spear points were burins, for carving bone and antler into harpoons and many other useful tools, and scrapers, for working hides.

The average band of perhaps twenty people hunted and butchered a reindeer on average every second day over the four months of summer, from June to September, so that the demands of food and clothing and replacement of tools could be met.

One large reindeer could provide up to 100 lbs, or 45 kg of meat. The reindeer hunters lived well in good times, with plenty to eat and no lack of resources for their lives.

Photo and text: Adapted from Caselli (1985)

Additional text: Bibby (1956) and http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=caribouhunting.main

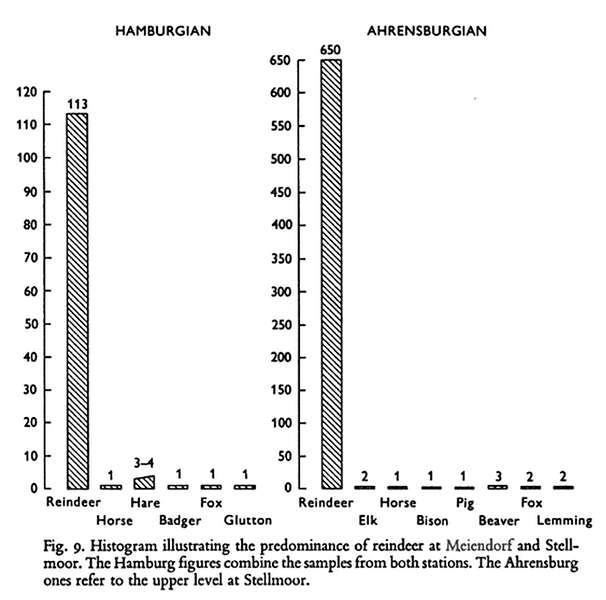

These graphs demonstrate the near total reliance on reindeer for sustenance and materials by both the Hamburgian and the Ahrensburg cultures.

Photo: Clark (1966)

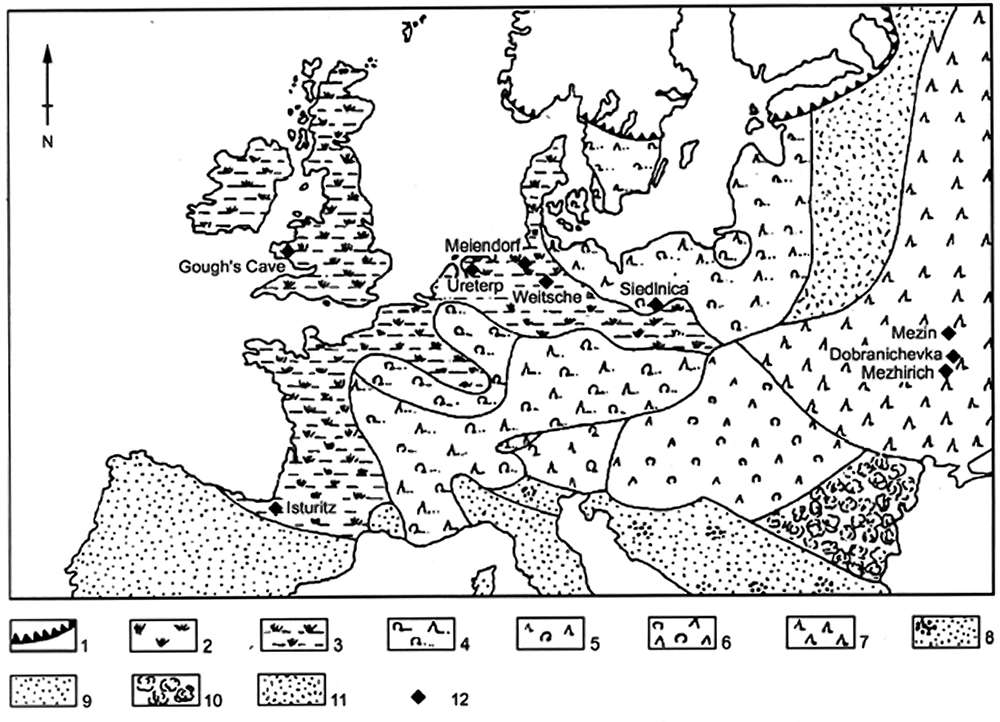

Map of the vegetation in Europe between 13 000 BP and 12 000 BP.

1 - Ice sheet

2 - Tundra

3 - Tundra 'xeric' variant (i.e. dry tundra)

4 - Birch-Pine forest

5 - Mixed forest

6 - Northern mixed conifer-deciduous forest

7 - Spruce dominated forest

8 - Steppe with Gramineae (now called Poaceae)

9 - Steppe (i.e. vast semi-arid grass-covered plain, as found in southeast Europe, Siberia, and central North America)

10 - Mixed-deciduous forest

11 - Mixed forest

12 - Sites with amber artefacts

Photo: Burdukeiwicz (1999)

Hunting on the tundra

The Cro-Magnons came to Europe in a mild climatic period. Their settlements were scattered all over central Europe. Slowly the climate got colder. When Ice Age glaciers covered northern Europe around 20 000 BP, man had moved further south. In southern Europe the hunting culture survived the coldest period of the Ice Age. When the climate improved people quickly moved north. Wild horses and mammoths lived on the tundra, but it was mainly reindeer hunting that brought humans to Denmark 14 000 years ago. Here the hunters pitched their tents on windswept hills with a view of the migration routes of the reindeer.

Sea level was still low at the end of the Ice Age, ca 9 000 BP. The Baltic Sea was full of meltwater that ran into the sea via a river in the Øresund. The reindeer had fixed migration routes on the tundra, and the hunters' settlements lay along these routes.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Stekers - Burins

A burin is a special type of lithic flake with a chisel-like edge which prehistoric humans used for engraving or for carving wood or bone. Burins exhibit a feature called a 'burin spall', in which toolmakers strike a small flake obliquely from the edge of the burin flake in order to form the graving edge. Burin usage is diagnostic of Upper Palaeolithic cultures in Europe.Text above: Wikipedia

Dubbele Stekers - Double Burins

Simple types of burins.

Photo: Inizan et al. (1999)

RA Stekers - RA type Burins - Blunted Burins

RA burins are made by breaking the end off a blade, blunting it, then using the coup de burin, the burin blow, to detach the burin spall by striking the blunted platform.Hamburgian Culture

The Hamburg culture or Hamburgian (15 500 - 13 100 BP) was a Late Upper Paleolithic culture of reindeer hunters in northwestern Europe during the last part of the Weichsel Glaciation beginning during the Bölling Interstatial. Sites are found close to the ice caps of the time.The Hamburg Culture has been identified at many places, for example, the settlement at Meiendorf and Ahrensburg north of Hamburg, Germany. It is characterised by shouldered points and zinken tools, which were used as burins when working with horns. In later periods tanged Havelte-type points appear, sometimes described as most of all a northwestern phenomenon. Notwithstanding the spread over a large geographical area in which a homogeneous development is not to be expected, the definition of the Hamburgian as a technological complex of its own has not recently been questioned.

The culture spread from northern France to southern Scandinavia in the north and to Poland in the east. In the early 1980s, the first find from the culture in Scandinavia was excavated at Jels in Sønderjylland. Recently, new finds have been discovered at, for example, Finja in northern Skåne. The latest findings (2005) have shown that these people traveled far north along the Norwegian coast dryshod during the summer, since the sea level was 50m lower than today.

In northern Germany, camps with layers of detritus have been found. In the layers, there is a great deal of horn and bone, and it appears that the reindeer was an important prey. The distribution of the finds in the settlements show that the settlements were small and only inhabited by a small group of people. At a few settlements, archaeologists have discovered circles of stones, interpreted as weights for a tent covering.

Text above: Wikipedia

Numerous reindeer standing on patches of snow during summer to avoid blood-sucking mosquitoes and gadflies. Reindeer migrate to summer pastures not just for the grazing, but to avoid the worst of the insects.

Photo: Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Text: adapted from Wikipedia

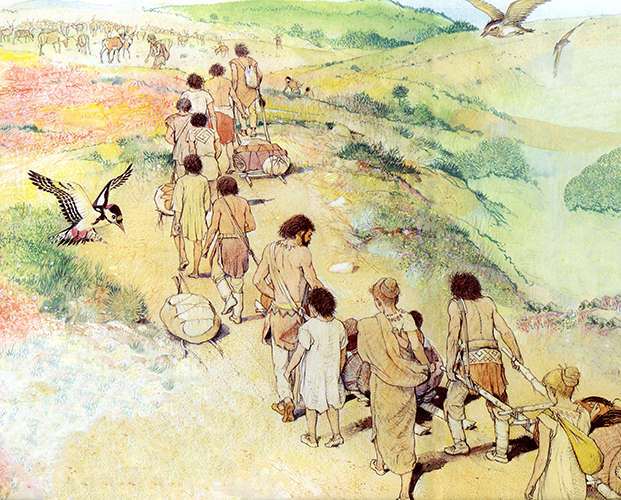

For weeks in the spring, the youngsters in the hunting band had been watching the reindeer in their winter, southern feeding grounds, and now the reindeer became restless, and began to move north to summer pastures. Their excited reports transformed the camp, which had been ready for this for a long time, and within a few hours everything was packed and in readiness for the long trek to the north, following the reindeer.

The reindeer mostly followed much the same path, but that was not always the case, and the life of the hunters was based around reindeer. Their main food was reindeer meat, though they varied it where possible, and their clothing, tools, weapons and tents were totally dependent on the harvest of reindeer.

The route taken by the huge herd of reindeer was easy to follow, but they never let the reindeer get too far ahead. The journey took a long time, but eventually they arrived in the north where the reindeer spread out on the tundra to graze, and the hunters set up camp near a good supply of water such as one of the glacial lakes that dotted the confused drainage of the tundra, and settled in for summer.

Photo and text: Adapted from Caselli (1985)

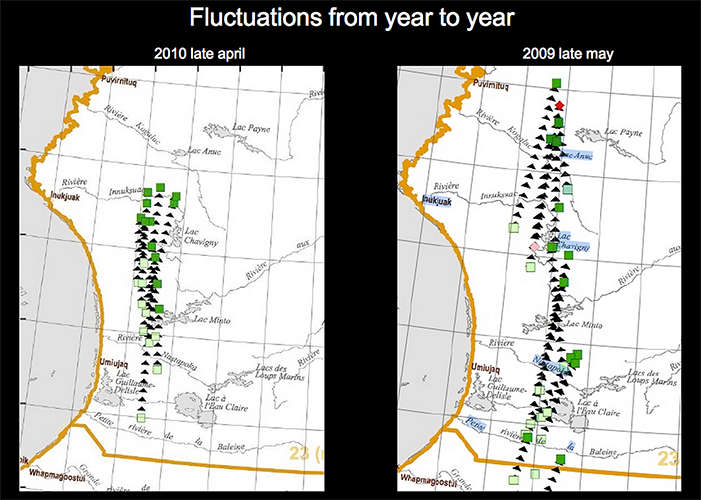

The reindeer hunters may have had to be flexible so far as meeting up with the migrations of the reindeer was concerned, depending on local conditions.

Migration paths were not necessarily fixed in stone, as these maps of the variation in caribou (reindeer) migrations on the shores of Hudson Bay, Canada, demonstrate.

Photo: Pedersen (2013)

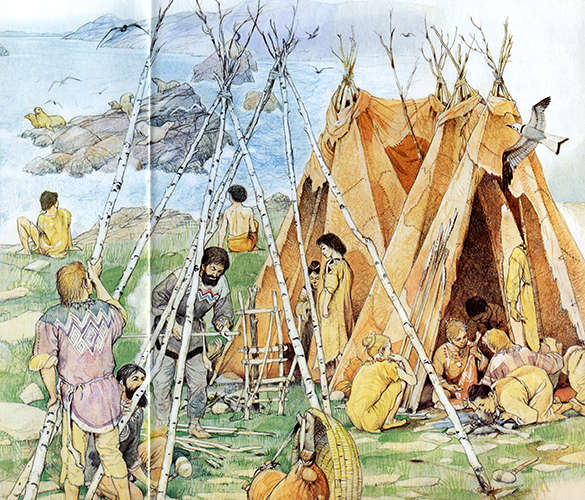

The people of the Hamburgian and Ahrensburg culture moved with the herds. Reindeer were their prime sustenance, for food, clothing, hides and weapons. This painting is more slanted to the Ahrensburg culture of Stellmoor, since the Hamburgian culture of Meiendorf mostly used spears thrown by spear throwers, and apparently did not have dogs, and the Ahrensburg mostly used bows and arrows, and had at least partly domesticated the dog. Both were summer camps to hunt reindeer, both were located by small lakes, and the two sites were only separated by 1300 metres.

Both had similar toolkit and cultural practices, including sacrificing the first prime reindeer of the season by sewing rocks in its abdominal cavity, and casting it into the lake. There was one such reindeer at the Hamburgian culture type site at Meiendorf, a site which was probably only used for one season, and more than thirty at the Ahrensburg culture at Stellmoor, a site which was used for a generation.

A reasonable hypothesis is that the Hamburgian culture typified by Meiendorf lasted from about 15 500 to 13 000 BP, and the Ahrensburg typified by Stellmoor existed from about 12 500 to 11 000 BP.

Photo: http://www.pkaj.dk/stellmoor_lokaliteten.asp

Bekstekers - Beaked Burins - Zinken

The beaked burin is especially common in the Middle Aurignacian. In appearance it rather resembles the prow of a ship turned upside down; the working edge is convex, being formed by a flat graver facet on one side, and a series of convex graver facets up the prow; this produces a keeled scraper made on the breadth of a blade. There are two sub-varieties, one with a notch to prevent the little convex graver facets from going too far down the blade, and the other without. Burkitt (1925)

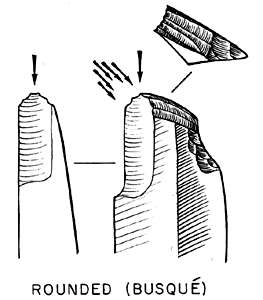

Burin busqué - the Beaked Burin

Burin busqué, n°1 : shelter 2, layer 2 and burin busqué of the Vachons type, n°2 : shelter 1, layer 2 (drawings D. Pesesse).

Photo and text: Pesesse et Michel (2008)

Burin busqué - the Beaked Burin

Three or more fairly regular spalls, often removed from a Spall Removal Surface (SRS) of dihedral type, approximate a semicircle. An edge of this shape is sometimes described as the gouge or busqué or hooked type.

(This is an excellent diagram of what I think of as a "classic" beaked burin, as described by Burkitt (1925). Note the front vertical spall, and the notch taken out of the rear of the burin to make sharpening easier, so that a spall comes off easily when retouching - Don )

Photo and text: Movius et al (1968)

This is the view that the hunters of the Perdeck site strived for - reindeer close by, the wind in the right direction, and an unseen approach!

The Perdeck camp site was on a small, isolated rise. About a kilometre away, there was a nine kilometre long, one kilometre wide ridge running north-south, elevated just five metres above the swampy tundra, but which would have provided both good grazing and an obvious solid, dry path for the reindeer as they travelled to and from their summer pastures.

Photo: © Jeroen van Iddekinge

Source: http://www.treknature.com/gallery/Europe/Norway/photo65128.htm

Dubbele Krombeksteker - Double ended curved tip beaked burin

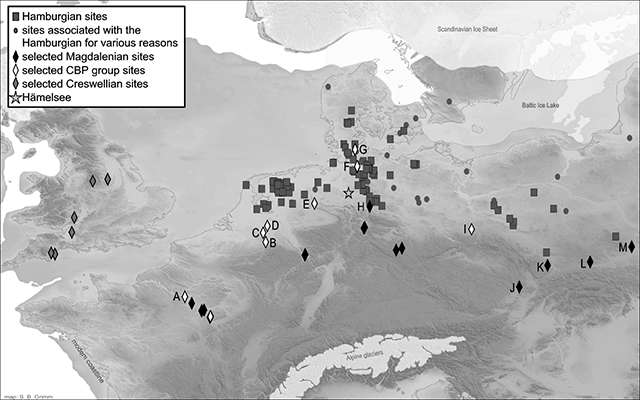

Distribution of the Hamburgian and sites associated with the Hamburgian in early Late glacial north-western Europe. Curve Backed Point (CBP) and Magdalenian sites labelled:

A – Le Closeau

B – Rekem

C – Budel

D - Milheeze-Hogeloop

E – Westerkappeln

F – Klein-Nordende

G - Alt Duvenstedt

H – Gadenstedt

I - Reichwalde,

J - Pekárna Cave

K - Dzierżysław 35

L - Maszycka Cave

M - Wilczyce

Photo and text: Grimm and Weber (2008)

On arrival at the summer camp site, which was often the same site as previous years, if the reindeer kept to their traditional path, the hunters erected their tents. If it was in the nearly treeless tundra, near the eternal ice, as was normal, they would have had to have taken the poles for the tents with them, perhaps using them lashed together and dragged behind the trudging men, doing double duty in holding their heavy loads of supplies for the journey, as well as clothes, weapons and tools. When they had served this purpose, they were reused for tent poles.

The camp site was always near a supply of fresh water, and in the confused drainage of the tundra, this was always available in the form of lakes which were ice free in the summer, and which provided a convenient place ( human nature has not changed much, after all! ) to toss all their defleshed bones, unwanted antlers, broken tools, and other rubbish, keeping the campsite itself clean and wholesome - a godsend for archaeologists many thousands of years later.

The first task on arrival was to make a fire, achieved by striking flint on a piece of pyrites, or marcasite, with the resultant sparks falling onto finely pounded willow bark, dried moss, or a fungus such as Fomes fomentarius. The embers thus created were then quickly blown into a fire with fine tinder, then larger diameter wood was added to get the campfire burning well.

Even in the tundra small trees sometimes grow in sheltered positions, but fuel would always have been a problem in these areas. Bone will burn, especially if it is old, dry bone, but it is not an ideal fuel, and is best used in conjunction with whatever wood can be scavenged (Äikäs et al., 2010).

This beautiful art work created by Giovanni Caselli shows them, however, camped beside the sea. Out of sight but close at hand would have been a convenient brook for fresh water.

Photo and text: Adapted from Caselli (1985)

Klingen - Blades

In archaeology a blade is a type of stone tool created by striking a long narrow flake from a stone core. Blades are defined as being flakes that are at least twice as long as they are wide and that have parallel or subparallel sides.Text above: adapted from Wikipedia

Additionally, a tool must be part of an intentional blade industry in order to properly be considered a blade; tools which show the characteristics of blades through variation but are not intentionally produced with those characteristics are not considered true blades. Blades became the favoured technology of the Upper Palaeolithic era, although they are occasionally found in earlier periods.

A soft punch or hammerstone is necessary in creating a blade and their long sharp edges made them useful for a variety of purposes. They were often worked to create scrapers or burins.

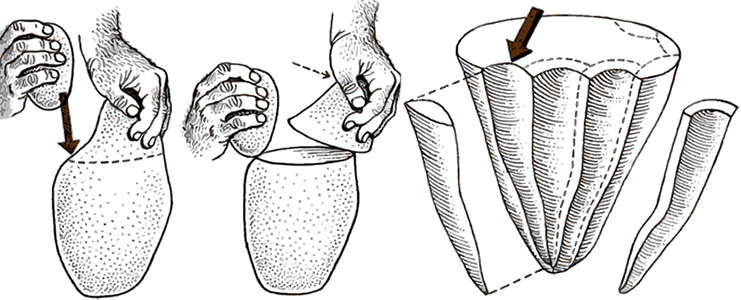

Blade Core Technique

A core for many blades is prepared by breaking a large flint nodule in two with a hammerstone. Using either piece, the maker then knocks long, thin flakes from the outside rim leaving a tapering fluted core. From this he produces a whole series of finished blades, striking them off one by one as he spirals around the nucleus.

By striking between ridges he will get a hollowed blade (top right). It has been estimated that a two-pound nucleus, flaked in this fashion, will yield some 25 yards of working edge, whereas a hand-axe shaped from the same stone would yield about four inches of effective edge.

Photo and text: Howell (1965), drawings by Lowell Hess.

Various Grattoirs-becs.

Photo and text: Delarue et Vignard (1959)

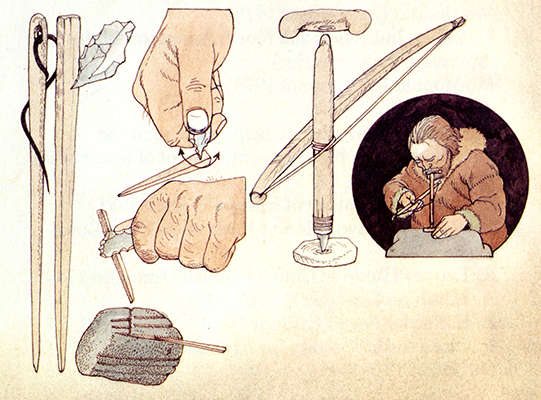

Drills were used as hand held tools and also hafted onto a handle to make them easier to use. Fine drills at the limit of the technology were needed to make holes in bone or antler needles to make the sewing of clothes easier. After the needles were created by scoring antler, the needles had a hole drilled in them, and were then fined down and rounded in grooves on pebbles of sandstone.

Photo: Caselli (1985)

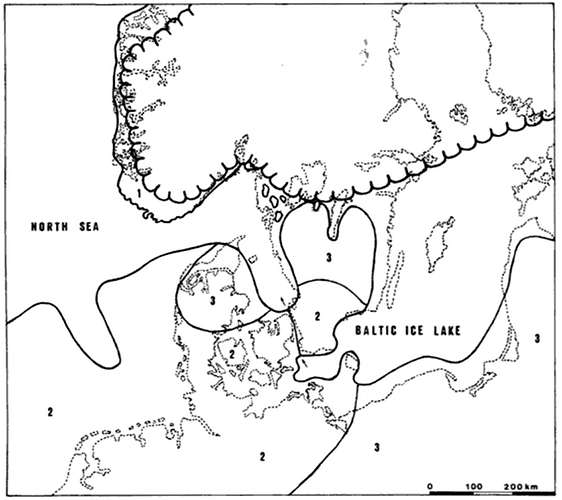

South Scandinavian land and sea configuration in Dryas III (ice margin at 10 000 BP)

1 - Tundra

2 - Park-Tundra with birch groves

3 - Sparse birch and pine forests

Readers may be interested in the dying stages of the last ice age, when reindeer hunters moved north onto the Scandinavian peninsula following the herds, in the process learning how to follow them across the fiords, and to invent the skin boats and adaptations of the spear and harpoon hunting tool kit necessary for this process, which then allowed them access to a hitherto untapped biome of fish and marine mammals.

This map shows the Baltic Ice Lake just before it joined with the North Sea, and the Vegetation Zones which were extant at that time.

Photo: Straus (1996)

References

- Äikäs, T., Vaneeckhout, S., Junno J., Puputti A., 2010: Prehistoric burned bone: use or refuse – results of a bone combustion experiment, Faravid, 2010/34: 7–15.

- Baron, D., Kufel-Diakowska, B., 2011: Written in Bones - Studies on technological and social contexts of past faunal skeletal remains, Uniwersytet Wrocławski,I nstytut Archeologii Wrocław 2011

- Baron, J., Michel, A., 2008: Le burin des Vachons : apports d’une relecture technologique à la compréhension de l’aurignacien récent du nord de l’Aquitaine et des Charentes, Paléo,18, 2008, 143-160

- Bibby, G., 1956: The Testimony of the Spade, Alfred A. Knopf, 424 pp.

- Burdukeiwicz, J., 1999: Late Palaeolithic Amber in Northern Europe, Investigations into Amber, Proceedings of the International Interdisciplinary Symposium, 2 - 6 September 1997 Gdansk, The Archaeological Museum Gdansk, Museum of Earth, Polish Academy of Sciences, Gdansk, 1999, pp 99-110.

- Caselli, G., 1985: The Everyday Life of an Ice Age Hunter, Macdonald & Co.

- Cheynier, A., 1963: Les burins, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France, 1963, tome 60, N. 11-12. pp. 791-803.

- Clark, G., 1966: Prehistoric Europe, Stanford University Press

- Delarue, R., Vignard E., 1959: Le grattoir-bec : un nouvel outil du Paléolithique supérieur, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France, 1959, tome 56, N. 5-6. pp. 358-363.

- Grimm, S., Jensen, D., and Weber, M., 2012: A lot of good points - Havelte points in the context of Late Glacial tanged points in Northwestern Europe, in A mind set on flint, Studies in honour of Dick Stapert. Groningen Archaeological Studies 16 (Groningen 2012), 251-266, Niekus, M. J. L. T., Barton, R. N. E, Street, M. & Terberger, T. (eds.)

- Grimm, S., and Weber, M., 2008: The chronological framework of the Hamburgian in the light of old and new 14C dates, Quartär, 55 (2008) : 17 - 40

- Howell, F., 1965: Early man, Life Nature Library. Time, Inc. New York 1965

- Inizan, M., Reduron-Ballinger, M., Roche H., Tixier J., 1999: Technology and Terminology of Knapped Stone, Préhistoire de la Pierre Taillée, CREP, Cercle de Recherches et d'Etudes Préhistoriques Maison de l'Archéologie et de l'Ethnologie (Boîte 3) 21, allée de l'Université - 92023 Nanterre Cedex - France Tome 5

- Instituut voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium (Zellik), 1994: Rekem, a Federmesser Camp on the Meuse River Bank, Volume II, Archeologie in Vlaanderen: Monografie, Leuven University Press, 1994, ISSN 1370-5768

- Movius H.L. Jr, David N., Bricker H., Clay B., 1968: The analysis of certain major classes of upper palaeolithic tools: Stratigraphy, American School of Prehistoric Research, Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Niekus, M., Street M., Barkhuis, T., 2012: A Mind Set on Flint: Studies in Honour of Dick Stapert, Groningen Archaeological Studies, 539 pp., ISBN -13: 9789491431135, ISSN: 1572-1760

- Pedersen, K., 2013: Humans and reindeer at Slotseng - 12 years after, Union Internationale des Sciences Préhistoriques et Protohistoriques,The Final Palaeolithic of Northern Eurasia, Schloss Gottorf, Event Date: Nov 6, 2013, https://www.academia.edu/5092764/Humans_and_reindeer_at_Slotseng_-_12_years_after

- Perdeck, M., 1993: Na 10 Jaar, APAN/EXTERN, 2 (1993).

- Pesesse, D., Michel A., 2008: Le burin des Vachons : apports d’une relecture technologique à la compréhension de l’aurignacien récent du nord de l’Aquitaine et des Charentes, Paléo, 18, 2008, 143-160

- Piette, E., 1907: L'art pendant l'Age du renne, Edouard Piette. - Paris: Masson & Cie., 1907. Pl. 60

- Riede, F., 2010: Hamburgian weapon delivery technology: a quantitative comparative approach, Before Farming, 2010, 1, ISSN 1476-4253

- Straus, L., 1996: Humans at the End of the Ice Age: The Archaeology of the Pleistocene-Holocene Transition, Springer, 30 Jun 1996 - History - pp. 378

- Weber, M., Grimm, S., 2007: Dating the Hamburgian in the Context of Lateglacial Chronology, Chapter One, Chronology and Evolution within the Mesolithic of North-West Europe: Proceedings of an International Meeting, Brussels, May 30th-June 1st 2007 , ed. Crombé P., Van Strydonck M., Sergant J., Boudin M., Bats M.

- Winick, C., 1956: Dictionary of Anthropology, Philosophical Library, 18 Dec 1956 - Social Science - 591 pages

Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites