Back to Don's Maps

Dinosaurs and other ancient animals

Dinosaurs, or Terrible Lizards, were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates for over 160 million years

This is Eoraptor, a typical dinosaur.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Eoraptor was one of the world's earliest dinosaurs. It was a two-legged carnivorous theropod that lived around 228 million years ago, in what is now the northwestern region of Argentina. The type species is Eoraptor lunensis, which means 'dawn plunderer from the Valley of the Moon', denoting where it was originally discovered. Paleontologists believe the Eoraptor resembles the common ancestor of all dinosaurs. It is known from several well-preserved skeletons.

It had a thin body that grew to about 1 metre (3 ft) in length, with an estimated weight of about 10 kilograms (22 lb), and stood as high as a man's knee. It ran upright on its hind legs. Its fore limbs were only half the length of its hind limbs and it had five digits on each 'hand'. Three of those digits, the longest of the five, ended in large claws and were presumably used to handle prey. Scientists have surmised that the fourth and fifth digits were too tiny to be of any use in hunting.

Eoraptor is thought to have eaten mostly small animals. It was a swift sprinter and, upon catching its prey, it would use claws and teeth to tear the prey apart. However, it had both carnivore-type and herbivore-type teeth, so it could possibly have been omnivorous.

Text: Wikipedia

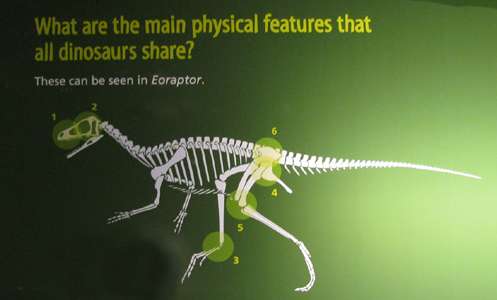

All dinosaurs share some main physical features, exemplified here by Eoraptor:

1. A hole in the skull between the eye socket and the nostril.

2. Two holes in the skull behind the eye socket.

3. An ankle that bends in a single plane like a hinge.

4. A hip socket with a hole in the centre.

5. Limbs held directly under the body.

6. Three or more sacral (located near the pelvis) vertebrae.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Tyrannosaurus rex head.

Built to crush bone, T. rex may have had the strongest bite of any animal ever.

Tyrannosaurus, from the Greek meaning 'tyrant lizard', is a genus of theropod dinosaur. The species Tyrannosaurus rex (rex meaning 'king' in Latin), commonly abbreviated to T. rex, is a fixture in popular culture. It lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the Maastrichtian age of the upper Cretaceous Period, 67 to 65.5 million years ago. It was among the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist prior to the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event.

Like other tyrannosaurids, Tyrannosaurus was a bipedal carnivore with a massive skull balanced by a long, heavy tail. Relative to the large and powerful hindlimbs, Tyrannosaurus forelimbs were small, though unusually powerful for their size, and bore two clawed digits. Although other theropods rivalled or exceeded Tyrannosaurus rex in size, it was the largest known tyrannosaurid and one of the largest known land predators, measuring up to 12.8 m (42 ft) in length, up to 4 metres (13 ft) tall at the hips, and up to 6.8 metric tons in weight. By far the largest carnivore in its environment, Tyrannosaurus rex may have been an apex predator, preying upon hadrosaurs and ceratopsians, although some experts have suggested it was primarily a scavenger. The debate over Tyrannosaurus as apex predator or scavenger is among the longest running debates in paleontology.

More than 30 specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex have been identified, some of which are nearly complete skeletons. Soft tissue and proteins have been reported in at least one of these specimens. The abundance of fossil material has allowed significant research into many aspects of its biology, including life history and biomechanics. The feeding habits, physiology and potential speed of Tyrannosaurus rex are a few subjects of debate. Its taxonomy is also controversial, with some scientists considering Tarbosaurus bataar from Asia to represent a second species of Tyrannosaurus and others maintaining Tarbosaurus as a separate genus.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney, with additional text from Wikipedia.

Sue, the T. rex.

Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago

Sue Hendrickson, amateur paleontologist, discovered the most complete (approximately 85%) and, until 2001, the largest, Tyrannosaurus fossil skeleton known in the Hell Creek Formation near Faith, South Dakota, on 12 August 1990. This Tyrannosaurus, nicknamed "Sue" in her honor, was the object of a legal battle over its ownership. In 1997 this was settled in favor of Maurice Williams, the original land owner.

The fossil collection was purchased by the Field Museum of Natural History at auction for USD 7.6 million, making it the most expensive dinosaur skeleton to date. From 1998 to 1999 Field Museum of Natural History preparators spent over 25 000 man-hours taking the rock off each of the bones. The bones were then shipped off to New Jersey where the mount was made. The finished mount was then taken apart, and along with the bones, shipped back to Chicago for the final assembly. The mounted skeleton opened to the public on May 17, 2000 in the great hall (Stanley Field Hall) at the Field Museum of Natural History.

A study of this specimen's fossilised bones showed that "Sue" reached full size at age 19 and died at age 28, the longest any tyrannosaur is known to have lived. Early speculation that Sue may have died from a bite to the back of the head was not confirmed. Though subsequent study showed many pathologies in the skeleton, no bite marks were found. Damage to the back of the skull may have been caused by post-mortem trampling. Recent speculation indicates that "Sue" may have died of starvation after contracting a parasitic infection from eating diseased meat; the resulting infection would have caused inflammation in the throat, ultimately leading "Sue" to starve because she could no longer swallow food. This hypothesis is substantiated by smooth-edged holes in her skull which are similar to those caused in modern-day birds that contract the same parasite.

Photo: Steve Richmond from Columbus

Permission: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

Edmontosaurus annectens

Order: Ornithischia

Suborder: Cerapoda

Infraorder: Ornithopoda

Diet: plants

Weight: approx. 3-4 tons

Length: approx. 10 metres

Age: 75-65 million years (Upper Cretaceous)

Fossil site: Wyoming (USA)

at Senckenberg: original

The only original skeleton of an Edmontosaurus in Europe is this one. In this specimen, even the structure of the skin has been preserved by a fossilised imprint. Worldwide, there are only two examples

in this state of preservation! The neck and front legs are sharply curved backward. It can be surmised from the cramped bodily posture of the animal, that these dinosaurs had already been dried up like mummies, before the body was covered up by sandy deposits. This way, the hardened skin could make an impression on the sediment and be preserved as a fossil imprint.

The mouth of the Edmontosaurus was surrounded by a horny beak. Its dentition was equipped with several hundred teeth. Together they formed a striking surface used to effectively crush the plants it took in.

To date, only a few dinosaurs have been found which still contained the fossilized stomach contents. In the uniquely well-preserved 'petrified mummy' in the Senckenberg Museum, in 1921 Prof. Kräusel discovered this animal's last meal. It consisted of needles of a common tree of the Cretaceous period, numerous small seeds and fruits, as well as the remains of twigs from conifers and deciduous trees.

The skin imprints on the feet show that Edmontosaurus ran on the balls of its feet, which is reminiscent of the modern camel. The Edmontosaurus was a representative of the widespread family of hadrosaurus. Previously, it was also known by the name Anatosaurus or Trachodon.

Gift of Arthur von Weinberg

Photo: Ralph Frenken 2012

Source: Senckenberg Naturmuseum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Triceratops elatus

Order: Ornithischia

Suborder: Cerapoda

Infraorder: Marginocephalia

Diet: plants

Weight: approx. 5 tons

Length: up to approx. 9 metres

Age: 70-65 million years (Upper Cretaceous)

Fossil site Montana (USA)

Everyone knows the Triceratops as an emblem of the Senckenberg Museum. Triceratops is the best known and largest representative of the widespread Cretaceous era family of Ceratopsidae. They are named for the three typical, up to a metre long, bony horns, which, in the living animal, were covered with a layer of horn. They could be used for defence against carnivorous dinosaurs. The mighty neck shield gave protection against neck bites. A ball joint at the back of his head made the Triceratops skull very mobile – a major advantage for defence with their dangerous horns.

Like all Ceratopsidae, Triceratops had a curved horny beak with which it could pinch off branches. The plant pieces were cut into small pieces in the mouth by the razor-sharp teeth, as with a pair of scissors, and then swallowed. Under each tooth were more replacement teeth, which could be put to use immediately when a tooth was worn out.

Fossilized footprints indicate that the animals lived in herds. Their arrangement also suggests that in case of danger, the young animals were brought into the centre of the herd for their protection. Some fossil skulls show damage. They are seen as having been wounded in disputes over rank in the herd. In at least one case there are traces of bites from the teeth of Tyrannosaurus.

The two skulls of Triceratops prorsus also in the collection are rare original pieces that were recovered in 1910 by Sternberg in the Laramie strata of Wyoming and offered for sale. In the same year, Braunfels made the acquisition of the two skulls possible for the Senckenberg Museum by a donation of 5 000 gold marks. After three years of preparation and assembly, the complete skull was exhibited as the 'first on the European continent'.

1911, Gift of O. Braunfels

Photo: Ralph Frenken 2012

Source: Senckenberg Naturmuseum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Quetzalcoatlus northropi

Suborder: Pterodactyloidae

Family: Azhdarchidae

Diet: probably fish

Wingspan: approx. 11 metres

Age: 70 million years (Upper Cretaceous)

Fossil site: Texas (USA)

At Senckenberg: cast (Original at the University of Texas, Austin/USA)

The reconstruction of the Quetzalcoatlus in the Senckenberg Museum is based on the original specimens, which are in the collections of the University of Texas at Austin, USA. The fossils found are only a number of neck vertebrae, the remains of a leg bone, skull fragments, and a nearly complete flying arm.

This may sound like very little, but together with other skeletal remains, which come from young animals, a fairly accurate picture of the skeletal anatomy of the Quetzalcoatlus can be reconstructed. The unpronounceable name of this Pterosaur genus is derived from the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl – 'Feathered Serpent'. It obtained the species name Northropi in honour of the brilliant aircraft designer, John K. Northrop.

Quetzalcoatlus northropi was probably a soarer, because the breast musculature necessary for active flight, must otherwise have reached enormous proportions. Despite its lightweight construction and the hollow, air-filled bones, a body weight of at least 75 kg must be assumed. Calculations showed that to be able to fly actively with so much weight, it would require in principle a breast muscle cross-section of 1 m diameter. For this, the body weight could no longer remain at 75 kg, making an even vaster muscle mass necessary, which would in turn increase the total weight, and so on.

If the animal could only soar, it was probably not able to actively launch itself. It is therefore assumed that the animal landed only rarely and then only on raised areas, such as high cliffs, where it would be easy to launch itself again. For the albatross, which weigh less than 10 kg, it is already very difficult start flying. Accordingly, they spend about 90% of their lives in the air. Therefore, we assume that Quetzalcoatlus northropi also remained almost continuously aloft, and took its food in flight. It remains unclear, what its prey might have been. It is possible that it fished, gliding just above the water and taking fish from the sea with its big toothless beak. However, the fossil bones were not found in marine sediments, but rather on the mainland.

Although knowledge about Pterosaurs has increased greatly in recent years, much still remains a mystery up to the present.

Photo: Ralph Frenken 2012

Source: Senckenberg Naturmuseum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Aurornis xui

Aurornis, a chicken-sized creature from Jurassic deposits in China, is every palaeontologist’s dream. The single exquisite fossil preserves virtually every bone in its natural position, including the tips of the tail, fingers and toes. Its anatomy demonstrates that it is one of the most bird-like dinosaurs yet discovered: in fact, it looks rather much like Archaeopteryx, but with shorter arms and hands, suggesting it had less developed wings.

But the nature of the flight feathers (if any) remains a mystery, as only a few patches of downy feathers are preserved. Nevertheless, Aurornis almost totally closes the gap between dinosaurs and birds. When the team re-analysed the evolutionary tree of dinosaurs and birds, adding Aurornis and examining more than twice as many anatomical traits as previous analyses, they found that Aurornis sat just below birds, with Archaeopteryx at the base of all birds.

Thus, the 160-million year old Aurornis and the 150-million-year-old Archaeopteryx provide excellent 'before' and 'after' snapshots of the evolution of bird flight. Furthermore, bird flight only evolved once, in an Archaeopteryx-like ancestor which gave rise ultimately to all other birds. There is now overwhelming evidence that birds evolved from bipedal, carnivorous dinosaurs, thanks largely to the wealth of feathered transitional fossils from China, which began emerging around 1998.

Fine volcanic ash instantly preserved these fossils with such fidelity that even their colour patterns can often be determined, based on pigment spots (melanosomes) in the feathers.

The full name of the new fossil (Aurornis xui) is both appropriate and slightly cheeky. It is named in honour of Xu Xing, the leading palaeontologist who has described many of these exceptional fossils, and aired the idea Archaeopteryx might not be a true bird (a proposal contradicted by the new fossil and analysis).

But there are many other important feathered fossils sitting in museums still to be described from China, and even more in the ground waiting to be discovered. Future work will undoubtedly further refine the smaller branches of the evolutionary tree between dinosaurs to birds.

Photo (fossil): © Thierry Hubin/IRSNB

Source: http://theconversation.com/

Photo (reconstruction): © Masato Hattori

Source: http://www.nature.com/news/new-contender-for-first-bird-1.13088

Text: Mike Lee, Senior Research Scientist, Evolutionary Biology at University of Adelaide

Source: http://theconversation.com/

Caudipteryx zoui

Like the stuff of nightmares, this superbly made dinosaur recreation is nevertheless based on fact. This dinosaur could not fly, but probably used its feathers for sexual display, and hence the brightly coloured plumage that was chosen by the artisan.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Caudipteryx zoui

The recreation is based on fossils from China. The dinosaur was alive in the Early Cretaceous, 130 - 125 million years ago.

Caudipteryx zoui was a small, bird-like theropod called an oviraptorisaurid, a group of nonavian theropod dinosaurs that occurred in Asia and Australia during the Cretaceous.

Caudipteryx means 'tail wing', referring to the tail plume that this non-avian dinosaur may have fanned out for display. The rest of the body was covered in short primitive feathers on its arms and tail.

Classification: Theropoda, Oviraptorosauria.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

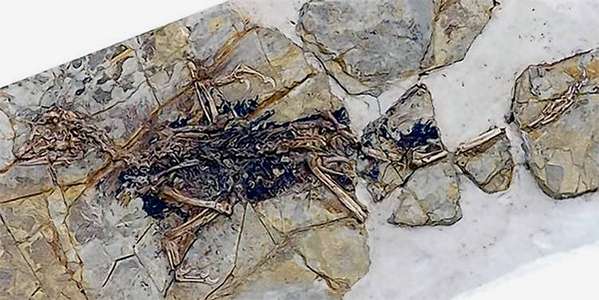

Caudipteryx zoui

This is one of the wonderfully well preserved fossils that was used in the reconstruction of the bird above.

It must have taken many hundreds or even thousands of hours to free this fossil from its matrix, then to painstakingly put it all together again for a stunning display.

This fossil is identified in catalogues as NGMC 97 9 A.

Gastroliths were found in this specimen. A gastrolith, also called a stomach stone or gizzard stones, is a rock held inside a gastrointestinal tract. Gastroliths are retained in the muscular gizzard and used to grind food in animals lacking suitable grinding teeth. The grain size depends upon the size of the animal and the gastrolith's role in digestion. Other species use gastroliths as ballast. Particles ranging in size from sand to cobbles have been documented.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Facsimile, display at the Australian Museum, Sydney

Text: Partially adapted from Wikipedia.

Archaeopteryx lithographica

Late Jurassic, 155 - 150 million years ago. This individual is the smallest Archaeopteryx found so far and is considered a juvenile. It was discovered in Germany in the 1950s.

Although this is a cast, the quality is wonderful, with beautiful colouring. Even the characteristic dendrites of black manganese dioxide which grow over millions of years in such conditions have been added to the cast. Modern museum facsimiles are often superbly made and presented, sometimes they are hard to distinguish from an original, which enhances their value as a teaching and research tool.

Classification: Theropoda, Aves.

It was found at a famous fossil site called Solnhofen in Germany.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Facsimile, cast, display at the Australian Museum, Sydney

Archaeopteryx lithographica

A beautifully made model in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

Photo: Ballista

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Source: Oxford University Museum of Natural History

Archaeopteryx lithographica

This image displays the tail of Archaeopteryx to advantage.

Photo: Ballista

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Source: Oxford University Museum of Natural History

Xiaotingia

A chicken-sized dinosaur fossil found in China may have overturned a long-held theory about the origin of birds. For 150 years, a species called Archaeopteryx has been regarded as the first true bird, representing a major evolutionary step away from dinosaurs, but the new fossil suggests this creature was just another feathery dinosaur and not the significant link that palaeontologists had believed.

The authors of the report in the journal Nature argue that three other species named in the past decade might now be serious contenders for the title of 'the oldest bird'. Archaeopteryx has a hallowed place in science, long hailed as not just the first bird but as one of the clearest examples of evolution in action. Discovered in Bavaria in 1861 just two years after the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, the fossil seemed to blend attributes of both reptiles and birds and was quickly accepted as the 'original bird'.

Photo: http://ultimosegundo.ig.com.br/

Text adapted from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-14307985

Xiaotingia

But in recent years, doubts have arisen as older fossils with similar bird-like features such as feathers and wishbones and three fingered hands were discovered. Now, renowned Chinese palaeontologist Professor Xu Xing believes his new discovery has finally knocked Archaeopteryx off its perch. His team has detailed the discovery of a similar species named Xiaotingia which dates back 155 million years to the Jurassic Period.

By carefully analysing and comparing the bony bumps and grooves of this new chicken-sized fossil, Prof Xu now believes that both Archaeopteryx and Xiaotingia are in fact feathery dinosaurs and not birds at all.

'There are many, many features that suggest that Xiaotingia and Archaeopteryx are a type of dinosaur called Deinonychosaurs rather than birds. For example, both have a large hole in front of the eye; this big hole is only seen in these species and is not present in any other birds.

Photo: http://ultimosegundo.ig.com.br/

Text adapted from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-14307985

Xiaotingia fossil

The origins of the new fossil are a little murky having originally been purchased from a dealer. Prof Xu first saw the specimen at the Shandong Tianyu Museum. He knew right away it was special.

'When I visited the museum which houses more than 1 000 feathery dinosaur skeletons, I saw this specimen and immediately recognised that it was something new, very interesting; but I did not expect it would have such a big impact on the origin of birds.'

Photo: http://www.latimes.com/

'Archaeopteryx and Xiaotingia are very, very similar to other Deinonychosaurs in having a quite interesting feature - the whole group is categorised by a highly specialised second pedo-digit which is highly extensible, and both Archaeopteryx and Xiaotingia show initial development of this feature.'

Several species discovered in the past decade could now become contenders for the title of most basal fossil bird:

Epidexipteryx - a very small feathered dinosaur discovered in China and first reported in 2008. It had four long tail feathers but there is little evidence that it could fly.

Jeholornis - this creature lived 120 million years ago in the Cretaceous. It was a relatively large bird, about the size of a turkey. First discovered in China, and reported in 2002.

Sapeornis - lived 110 to 120 million years ago. Another small primitive bird about 33 centimetres in length. It was discovered in China and was first reported in 2002.

Other scientists agree that the discovery could fundamentally change our understanding of birds. Prof Lawrence Witmer from Ohio University has written a commentary on the finding.

'Since Archaeopteryx was found 150 years ago, it has been the most primitive bird and consequently every theory about the beginnings of birds - how they evolved flight, what their diet was like - were viewed through the lens of Archaeopteryx So, if we don't view birds through this we might have a different set of hypotheses.' There is a great deal of confusion in the field says Prof Witmer as scientists try to understand where dinosaurs end and where birds begin.

'It's kind of a nightmare for those of us trying to understand it. When we go back into the late Jurassic, 150-160 million years ago, all the primitive members of these different species are all very similar. So, on the one hand, it's really frustrating trying to tease apart the threads of this evolutionary knot, but it's really a very exciting thing to be working on and taking apart this evolutionary origin.'

When Professor Xu saw this skeleton of Xiaotingia zhengi in a museum, he knew right away it was special.

Such are the similarities between these transition species of reptiles and birds that other scientists believe that the new finding certainly will not mean the end of the argument.

Prof Mike Benton from the University of Bristol, UK, agrees that the new fossil is about the closest relative to Archaeopteryx that has yet been found. But he argues that it is far from certain that the new finding dethrones its claim to be the first bird.

'Professor Xu and his colleagues show that the evolutionary pattern varies according to their different analyses. Some show Archaeopteryx as the basal bird; others show it hopped sideways into the Deinonychosaurs. New fossils like Xiaotingia can make it harder to be 100% sure of the exact pattern of relationships.'

According to Prof Witmer, little is certain in trying to determine the earliest bird and new findings can rapidly change perspectives.

'The reality is, that next fossil find could kick Archaeopteryx right back into birds. That's the thing that's really exciting about all of this.'

Text above adapted from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-14307985

And from the delightful, inimitable and thankfully irrepressible P.Z. Meyers, a biologist and associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Morris, and author of the Pharyngula blog:

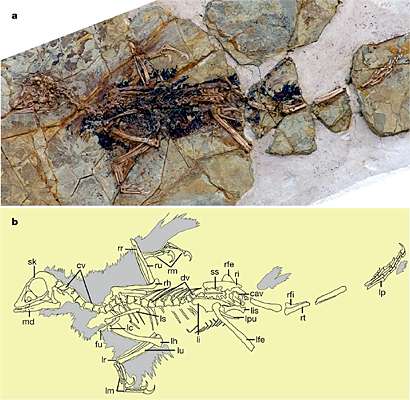

Xiaotingia zhengi

a, b, Photograph (a) and line drawing (b). Integumentary structures in b are coloured grey. cav, caudal vertebra; cv, cervical vertebra; dv, dorsal vertebra; fu, furcula; lc, left coracoid; lfe, left femur; lh, left humerus; li, left ilium; lis, left ischium; lm, left manus; lp, left pes; lpu, left pubis; lr, left radius; ls, left scapula; lu, left ulna; md, mandible; rfe, right femur; rfi, right fibula; rh, right humerus; ri, right ilium; rm, right manus; rr, right radius; rt, right tibiotarsus; ru, right ulna; sk, skull; ss, synsacrum.

A lovely new dinosaur fossil from China is described in Nature today: it's named Xiaotingia zhengi, and it was a small chicken-sized, feathered, Archaeopteryx-like beast that lived about 155 million years ago. It shares some features with Archaeopteryx, and also with some other feathered dinosaurs.

Now here's why this particular fossil has some paleontologists in a dither. Systematics uses a set of objective, computer-based tools to objectively build phylogenetic trees: you plug a set of character parameters for a set of organisms into it, and it analyzes them and determines the most likely or most parsimonious tree to describe their relationships. Plugging in data from modern birds, Archaeopteryx, and dromeosaurs, for instance, generates trees in which Archaeopteryx clusters with the birds, and not the dromeosaurs. Archaeopteryx was not a direct ancestor of modern birds, but was thought to be related to the basal avians — so it was a kind of close cousin.

When Xiaotingia's data is tossed into the calculation, though, the results change. Xiaotingia doesn't cluster so tightly with birds; it's a more distant relative. However, Archaeopteryx shares enough significant features with Xiaotingia that they now cluster together, pulling Archaeopteryx out of the basal Aves and into a new classification. It says that Archaeopteryx is now a kind of second cousin, a little less closely related to the birds than previously thought.

Archaeopteryx has historically been regarded as the most basal bird (avialan), but the discovery of the closely related Xiaotingia led Xu et al.(2011) to pull these archaeopterygids out of avialans (birds) and into deinonychosaurs along with dromaeosaurids and troodontids. This new grouping better accounts for the evolution of feeding strategies among bird-like dinosaurs. Previous research suggested that herbivory was common among this group, as reflected in the tall, boxy skulls of oviraptorosaurs and basal avialans such as Epidexipteryx. The triangular, sharp-toothed skull of Archaeopteryx was incongruous among basal avialans, but fits better among the carnivorous dromaeosaurids and troodontids.

I have to say that I think it's extremely cool that we have a new fossil from down around the roots of the bird family tree, and it does sharpen our knowledge of what was going on down there in the middle and late Jurassic. There was a whole assortment of delicate-boned, feathered, bipedal dinosaurs that were flourishing and diversifying in that window of time, and we've now got enough data that we can distinguish details in the family tree, which is absolutely fabulous.

However, a lot of the fuss over the specimen as somehow radically changing the importance of Archaeopteryx is a bit overblown. The relative status of Archaeopteryx and Xiaotingia is a bit of taxonomic detail — important details in working out the specific history of life — but it's the equivalent of deciding that a fossil belongs in one pigeonhole rather than the pigeonhole next to it. Its shift in status means that there's a bigger gap in the early history of the true birds than we thought, and it also means that there was a greater diversity of bird-like forms than we expected in the Jurassic. One other suggestion is that removing the carnivorous Archaeopteryx from the base of the bird family tree opens up the possibility that modern birds might have descended from the vegetarian side of the family — if the last common ancestor of birds was an herbivore, that has interesting implications for the paths evolution took.

But don't worry, Archaeopteryx still represents a beautiful example of a transitional form. This new fossil is just another transitional form discovered. Creationists cannot take any consolation from it: Archaeopteryx isn't suddenly gone, it's become a part of a richer picture of bird evolution.

Posted by PZ Myers at 2:10 PM 28th July 2011

Photo and text: http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/

Source: Xu et al.(2011)

Muttaburrasaurus langdoni

Name derived from: Muttaburra, site of its discovery.

Pronounced: mutta-burra-SAWR-us

Lifestyle: This large plant-eater probably ate cycads, which were common at the time, and also club-mosses, ferns, and podocarps. It may have lived in herds.

Features: Muttaburrasaurus had an unusual skull with a bony lump on the snout. The skin over the snout may have inflated to make loud calls or could have been brightly coloured and used for display purposes. Muttaburrasaurus could have walked on two or four limbs, and probably stood on its back legs to reach food.

Classification: Ornithopoda; Iguanodontia

Lived: Early Cretaceous, 112-100 million years ago.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Muttaburrasaurus langdoni

The name Muttaburrasaurus langdoni is on honour of Doug Landon, the grazier who first discovered the fossils near Muttaburra in Queensland in 1963.

Interestingly, here may have been more than one species of Muttaburrasaurus. Fossils from north-central Queensland and Lightning Ridge, NSW, differ slightly from the original Muttaburra specimens.

Photo: Muttaburrasaurus statue in Hughenden, outback Queensland, Australia

Date: 17 July 2007 by GondwanaGirl

This work has been released into the public domain

Muttaburrasaurus langdoni skull at the Australian Museum, Sydney.

Date: 20 April 2008 by Matt Martyniuk (Dinoguy2)

Permission: Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2

Pterosaur

Rhamphorynchus muenseri

Germany

Late Jurassic, 150 - 140 million years ago

Rhamphorynchus was a long-tailed and small-bodied pterosaur. This group of pterosaurs dominated the skies in the Triassic and Jurassic. The tail was thickened with thick bony rods and was probably used for steering. They were related to the dinosaurs.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Pterosaurs, often referred to as pterodactyls, were flying reptiles of the clade or order Pterosauria. They existed from the late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous Period (220 to 65.5 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight. Their wings were formed by a membrane of skin, muscle, and other tissues stretching from the legs to a dramatically lengthened fourth finger. Early species had long, fully-toothed jaws and long tails, while later forms had a highly reduced tail, and some lacked teeth. Many sported furry coats made up of hair-like filaments known as pycnofibres, which covered their bodies and parts of their wings. Pterosaurs spanned a wide range of adult sizes, from the very small Nemicolopterus to the largest known flying creatures of all time, including Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx.

Pterosaurs are sometimes referred to in the popular media as dinosaurs, but this is incorrect. The term "dinosaur" is properly restricted to a certain group of terrestrial reptiles with a unique upright stance (superorder Dinosauria), and therefore excludes the pterosaurs, as well as the various groups of extinct marine reptiles, such as ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs.

Text: Wikipedia

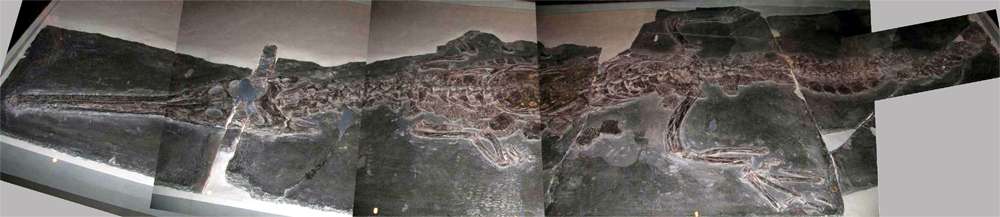

Ichthyosaur

Stenopterygius quadriscissus

Middle Jurassic, 183 - 176 million years ago

Stenopterygius was an icthyosaur, a fish-like marine reptile. Ichthyosaurs first appeared in the Triassic and became extinct in the Cretaceous.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Marine crocodilian

Steneosaurus bollensis

Early Jurassic, 183 - 176 million years ago

Steneosauruslooked very similar to modern crocodiles, except for its small front legs. It belonged to the teleosaurid family of crocodilians that became extinct about 130 million years ago.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

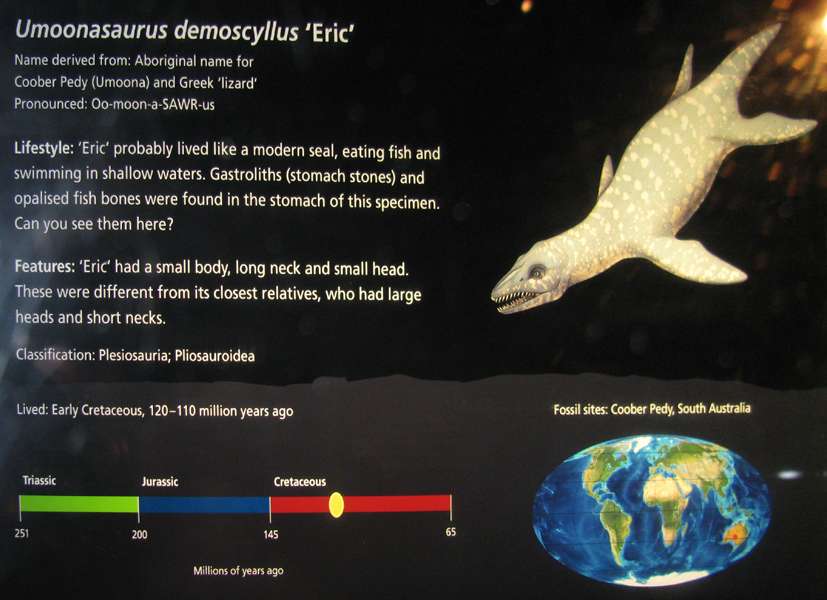

Eric

Umoonasaurus demoscyllus 'Eric'

Name derived from: Aboriginal name for Coober Pedy (Umoona) and Greek 'lizard', pronounced: Oo-moon-a-SAWR-us

Lifestyle: 'Eric' probably lived like a modern seal, eating fish and swimming in shallow waters. Gastroliths (stomach stones) and opalised fish bones were found in the stomach of this specimen.

Can you see them in the photo of the skeleton above?

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Original, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Text below from http://home.alphalink.com.au/~dannj/eric.htm

In 1993 there were rumours that Eric was to be sold overseas. To keep it in Australia the science program "Quantum", in association with the Australian Museum in Sydney, asked for public donations. Around 30 000 people responded, raising $450 000 Australian. Eric's opal content alone was estimated at $25 000 AU. The unprepared and fragmented skeleton was initially bought by a developer for $125 000. The "Quantum" appeal money bought the skeleton for $320 000 when the developer went bankrupt, with the rest of the money raised put into a fund for future purchases.

Features: 'Eric' had a small body, long neck and small head. These were different to its closest relatives, who had large heads and short necks.

'Eric' was named after a Monty Python sketch in which all the animals were called Eric.

This important specimen was found by an opal miner in 1987. It became part of the Australian Museum collections in 1993 after it was bought with donations from Akubra and the school children of Australia.

Classification: Plesiosauria; Pliosauroidea

Lived: Early Cretaceous, 120 - 11- million years ago

Fossil site: Coober Pedy, South Australia

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Mesosaur, Brazilosaurus sanpauloensis

Brazil, Permian, 253 million years ago.

Fossils of this freshwater reptile have been found in Africa and South America.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Display at Australian Museum, Sydney

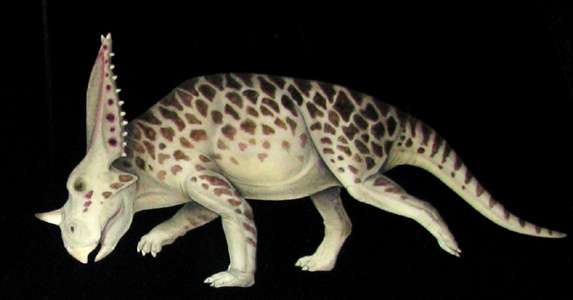

Chasmosaurus belli

Name derived from the Greek, 'Opening Lizard'

Lifestyle: Chasmosaurus lived in large herds. Bone-beds containing the remains of 200 - 300 animals have been found.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Chasmosaurus belli

Features: This species belongs to the long-frilled group of ceratopsians. The two large holes, or fenestrae (windows) in the skull were covered with skin and may not have been suitable for defence. Fossilised skin impressions show the body was at least partially covered with bony knobs.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Chasmosaurus belli

Classification: Marginocephalia; Ceratopsia.

Lived: Late Cretaceous, 76 - 71 million years ago.

Fossil sites: Canada, North America.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney

Fulgurotherium australe is the smaller blue dinosaur, the other two are Dromaeosaur-like theropods, full size dinosaurs,

© www.studiooxmox.com

Fulgurotherium australe was a small ornithopod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Australia. Fulgurotherium, known from Lightning Ridge in New South Wales and perhaps from Victoria, was one of the first Australian dinosaurs to be scientifically described.

Lightning Ridge was on or near the palaeo-Antarctic Circle during the Early Cretaceous, and Fulgurotherium would have been adapted to survive in this extreme environment. The status of Fulgurotherium is uncertain both because of its fragmentary nature and because the relationships of all Australian ornithopods are poorly understood.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney, additional text from http://australianmuseum.net.au

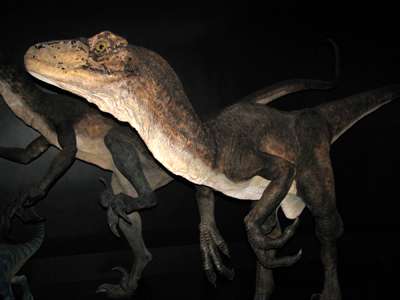

Dromaeosaur-like theropod, © www.studiooxmox.com

Dromaeosauridae is a family of bird-like theropod dinosaurs. They were small- to medium-sized feathered carnivores that flourished in the Cretaceous Period. The name Dromaeosauridae means 'running lizards', from the Greek dromeus meaning 'runner' and sauros meaning 'lizard'. In informal usage they are often called raptors (after Velociraptor), a term popularised by the film Jurassic Park; a few types include the term 'raptor' directly in their name and have come to emphasise their supposed bird-like habits.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney, additional text from Wikipedia.

Dromaeosaur-like theropod, © www.studiooxmox.com

Dromaeosaurid fossils have been found in North America, Europe, Africa, Japan, China, Mongolia, Madagascar, Argentina, and Antarctica. They first appeared in the mid-Jurassic Period (late Bathonian stage, about 164 million years ago) and survived until the end of the Cretaceous (Maastrichtian stage, 65.5 million years ago), existing for 100 million years, up until the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event.

The presence of dromaeosaurs as early as the Middle Jurassic has been confirmed by the discovery of isolated fossil teeth, though no dromaeosaurid body fossils have been found from this epoch.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney, additional text from Wikipedia.

Qantassaurus probably relied on camouflage to escape hungry predators.

(Note that Qantas is Australia's national airline! - Don)

This is a life-sized reconstruction, based on fossils from Victoria, Australia.

Early Cretaceous, 106 million years ago.

Classification: Ornithopoda; Euornithopoda.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney.

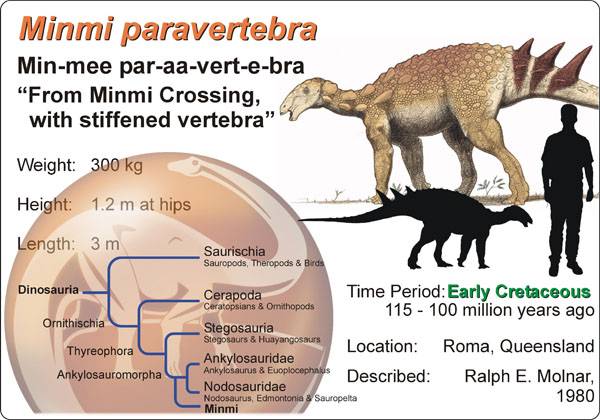

Minmi paravertebra (life sized reconstruction)

Name derived from: Site where first discovered, near Minmi Crossing, Queensland, Australia.

Pronounced: MIN-my

Lifestyle: There is no evidence that Minmi lived in herds. Fossilised gut contents show it ate seeds and leaves of flowering plants.

Features: Like all ankylosaurs, Minmi had longer back legs than front legs. This moved its centre of gravity forwards, providing extra stability when assuming a defensive posture. However, its legs were longer than other ankylosaurs so it may have moved faster. It lacked the tail-club of most ankylosaurids.

Classification: Thyreophora; Ankylosauria.

Lived: Early Cretaceous, 125 - 110 million years ago.

Fossil sites: Hughenden, Roma and Richmond, Queensland, Australia.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney.

Photo: © National Dinosaur Museum, Canberra

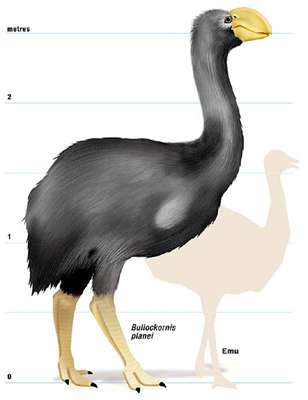

This giant bird goes by the name of 'Demon Duck of Doom'!

Bullockornis planei (Skull)

Bullockornis planei, nicknamed the Demon Duck of Doom, is an extinct flightless bird that lived in the Middle Miocene, approximately 15 million years ago, in what is now Australia.

This specimen comes Bullock Creek, Northern Territory.

Bullockornis planei stood approximately 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) tall. It may have weighed up to 300 kg. Features of Bullockornis's skull, including a very large beak suited to shearing, indicate that the bird may have been carnivorous. The bird's skull is larger than that of many small horses. Many paleontologists, including Peter Murray of the Central Australian Museum, believe that Bullockornis was related to geese and ducks. This, in addition to the bird's tremendous size and possible carnivorous habits, gave rise to its colourful nickname.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source: Possibly original, display at Australian Museum, Sydney, with additional text adapted from Wikipedia.

Bullockornis planei in Kings Park, Perth, Western Australia, and a representation of the giant bird from New Scientist.

Photo (left): Seanmack

Permission: GNU Free Documentation License.

Photo (right): New Scientist Magazine

Bullockornis belonged to a uniquely Australian family of extinct flightless birds called the dromornithids, or thunder birds. These huge birds were once some of the most conspicuous members of the Australian fauna. They lived on the continent from at least 24 million years ago until 50 000 years ago and perhaps more recently still. The last of the family, Genyornis newtoni, almost certainly overlapped with the first humans.

Towards the end of 1998, Peter Murray and Dirk Megirian, fossil experts from the Central Australian Museum in Alice Springs, provided the first glimpse of the face of one of Australia's long-dead giants. They had finally pieced together enough skull fragments to reconstruct Bullockornis's head and beak. Unlike emus or ostriches, which have tiny heads perched on long, sinuous necks, this bird's head was huge-almost half a metre long-and ended in a deep, curved beak.

Researchers Murray and Megirian decided that the bird's gigantic beak was a specialised cutting tool for shearing through the toughest parts of plants-twigs, leathery-coated fruits or seed pods or large nuts with hard shells. With its long legs and neck, they suggested, Bullockornis browsed in the lower branches of trees, 2 or 3 metres off the ground.

Steve Wroe, however, a palaeontologist at the University of Sydney and the Australian Museum, is in no doubt that this bird ate flesh. "The beak was a huge pair of secateurs that could scissor out chunks of meat," he says. "It could hook into your thigh and rip out a nice slab of meat quite easily." Wroe believes that the massive head and beak with industrial-strength muscles were adaptations for slicing through meat. "From the power generated in the bite, it's difficult to rationalise as something that cracked open seed pods or munched on leaves and suchlike," he says.

Text above adapted from New Scientist Magazine, 27 May 2000, by Stephanie Pain

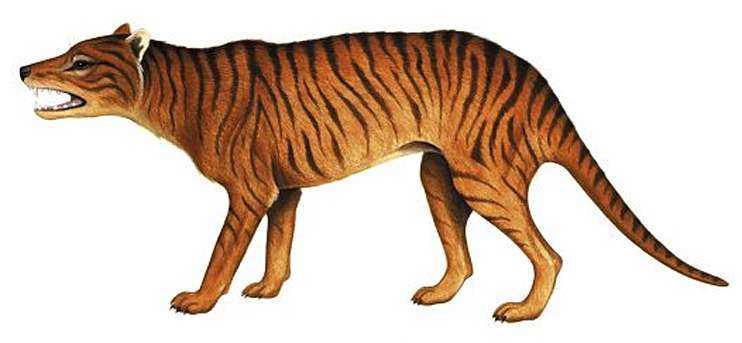

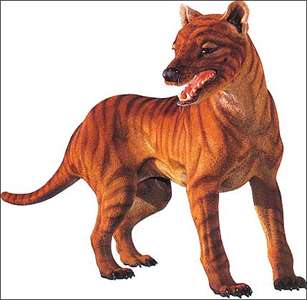

The Powerful Thylacine, Thylacinus potens

Thylacinus potens ("powerful thylacine") was the largest species of the family Thylacinidae, known from a single poorly preserved fossil discovered by Michael O. Woodburne in 1967 in a Late Miocene locality near Alice Springs, Northern Territory. It preceded the modern thylacine by 4–6 million years, was 5% bigger, was more robust and had a shorter, broader skull. Its size is estimated to be similar to that of a grey wolf; the head and body together were around 5 feet long, and its teeth were less adapted for shearing compared to those of the modern thylacine.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Facsimile, display at Australian Museum, Sydney, additional text from Wikipedia

The Powerful Thylacine lived during the Late Miocene, about seven to eight million years ago. It weighed up to 37 Kilograms, and was one of the largest thylacines to have ever lived. It had a robust jaw, giving it a powerful bite. Like other marsupials, it would have had a pouch.

It was a predator able to kill relatively large prey, and lived in dry, open forests. The only fossils of this thylacine were found at Alcoota in the Northern Territory. It is now extinct, but it is not clear how this happened, as there are so few fossils. Its closest living relatives are the Dasyurid marsupials such as Tasmanian Devils, Quolls, Antechinuses and Dunnarts.

Text above: Display, Australian Museum, Sydney, Australia.

The Powerful Thylacine, Thylacinus potens

Scientific classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Mammalia

Infraclass: Marsupialia

Order: Dasyuromorphia

Family: †Thylacinidae

Genus: †Thylacinus

Species: Thylacinus potens

Thylacinus potens ("powerful thylacine") was the largest species of the family Thylacinidae, known from a single poorly preserved fossil discovered by Michael O. Woodburne in 1967 in a Late Miocene locality near Alice Springs, Northern Territory. It preceded the modern thylacine by 4–6 million years, and was 5% bigger, was more robust and had a shorter, broader skull. Its size is estimated to be similar to that of a grey wolf; the head and body together were around 5 feet long, and its teeth were less adapted for shearing compared to those of the modern thylacine.

Lived: 8 million years ago (late Miocene)

Size: Length (head and body): 1.5m

Fossils: A partial skull of the Powerful Thylacine was found at Alcoota Station in the Northern Territory.

Photo: © Anne Musser

Source and text: http://australianmuseum.net.au, http://www.carnivoraforum.com/

The Powerful Thylacine, Thylacinus potens

A reconstruction of Thylacinus potens, a powerful predatory member of the thylacine family which lived 8 million years ago and was similar in size to a rottweiler.

Photo: © Dr Stephen Wroe, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Institute of Wildlife Research, school of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney.

Source: http://www.smh.com.au/

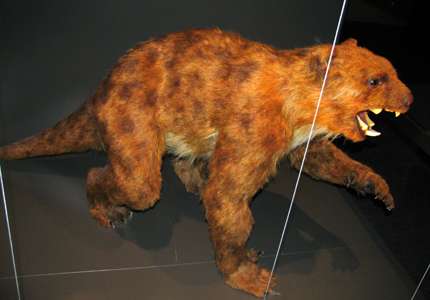

The largest of the marsupial lions, Thylacoleo carnifex.

It lived from about 1.8 million years ago, dying out about 30 000 years ago.

It had a heavy, muscular body weighing up to 130 kilograms! It had opposable thumbs, with large, curved claws like flick-knives. It had strong arms for gripping prey, and specialised teeth for stabbing and holding prey and for slicing through flesh. It had a robust, broad skill with a short snout, giving it a powerful bite.

Photo: (left) Don Hitchcock 2010, taken at the Australian Museum, Sydney

Photo: (right) Karora 2006, A skeleton of a Marsupial Lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) in the Victoria Fossil Cave, Naracoorte Caves National Park

Permission for the photo on the right: Public domain

Note the large incisors of the Marsupial Lion for stabbing prey, and the enormous, blade-like premolars for slicing through flesh in this photo of half the jaw of a marsupial lion.

It was carnivorous. Its enormous, blade-like teeth - ideal for slicing through flesh, hide, and sinew - indicate it was a meat-eater but not a bone cruncher (a predator rather than a scavenger).

It was widespread across Australia - its fossils are common all over the country. It may have become too specialised for its own good. While it was exceptionally good at grabbing, wrestling, biting and tearing, it may have been too bulky to run down fast, agile prey. As the large, slow-moving megafauna died out, so too did their most specialised predator.

Its closest living relatives are either wombats and koalas, or possums.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2010

Source and text: Australian Museum, Sydney

References

- Xu X., You H., Du K. Han F., 2011: An Archaeopteryx-like theropod from China and the origin of Avialae. Nature 475, 465-470.