Back to Don's Maps

Grotte de la Vache in the Pyrenees was home for the artists of Niaux Cave

La Grotte de la Vache is important for the complete camp of Magdalenian hunters found, and may be seen almost as it was 12 000 to 15 000 years ago. Weapons, tools, typical game and artworks have been recovered from this small but important site. It was the living quarters for the artists of Niaux Cave, or la Grotte de Niaux.

Panorama of the meeting room, the Salle Monique at Grotte de la Vache

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Note - Use this pdf file if you wish to print this map on a single sheet of paper.

Photo: Don Hitchcock version 2012/05/26

The sign beside the path to the Grotte de la Vache.

Photo: Ralph Frenken 2019

The path to Grotte de la Vache, with the entrance just coming into view.

Photo: Courtesy Elise Meyer 2011

Entrance to Grotte de la Vache. The name, Cave of the Cow, is due to a natural sculpture near the entrance to the cave which looks something like a cow.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Grotte de la Vache faces south east. It would have been a lovely place to come out of on a sunny day, into the sunshine, even in the middle of winter. Certainly the valley would have kept it shaded very early in the morning in winter, but the sun would soon have swung over the valley walls and down the broad valley to the Grotte de la Vache, even in winter.

The photos taken of the entrance, above, were at ten am (summer time) in August, and it was a very pleasant place to ramble around the area while I waited for the first tour. If you mentally subtract the shade from the trees, which would have been stunted if they had been there at the time of the Magdalenian hunters, or more likely non-existent, you can get some idea of the ideal aspect of the cave entrance. Even in the middle of winter, and the inhabitants spent the winter here, feasting on the ibex which came down from their summer pastures in the high peaks and valleys to graze on the broad grassy floor of the Vicdessos valley, there would have been sunshine in the middle of the day.

For Grotte de Niaux and Grotte de la Vache:

Latitude : 42.8167N

Longitude : 1.5833E

As seen here in a photo taken from Grotte de la Vache, Grotte de Niaux is just across the Vicdessos valley, about 500 metres away.

The Niaux cave entrance is behind the brown sculpture visible in the middle of the cliff face, in line with the approach road.

The paintings of Grotte de Niaux were almost certainly done by the people who made Grotte de la Vache their winter home. There is no evidence of occupation of Grotte de Niaux, which would have been comparatively cold and drafty and dark compared with Grotte de la Vache.

Photo: http://www.prehistoirepassion.com/grotte%20la%20vache.htm

In this photo we can see that both cave entrances are now obscured from direct sight because of the trees at both sites, at least in summer.

Photo: Courtesy Elise Meyer 2011

A panorama of the view down the valley of the Vic-Dessos from near the entrance to Grotte de la Vache, taken from the path about thirty metres before the entrance to the cave. The brown steel triangle at the entrance to Grotte de Niaux may be seen towards the upper right of this photo. (click to expand)

Photo: Courtesy Elise Meyer 2011

The entrance to Niaux faces more north west, but it is so large that west is close enough, especially given the enormous flat entry porch - a wonderful vantage point for looking for game. Even in winter, the setting sun, to the south west, would flood the entrance way with light.

Approximate maximum and minimum times of sunrise and sunset, if we make noon at the middle of the day:

Summer 04.30h to 19.30h, or 4.30 am to 7.30 pm, 15 hours of sunshine per day.

Winter 07.30h to 16.30h, or 7.30 am to 4.30 pm, 9 hours of sunshine per day.

North has an azimuth value of 0 degrees, east is 90 degrees, south is 180 degrees, and west is 270 degrees.

The sun rises and sets in summer with azimuths of 56° and 304° - this means that the sun rises at NE by E in summer, and sets at NW by W.

The sun rises and sets in winter with azimuths of 122° and 238° - this means that the sun rises at SE by E in winter, and sets at SW by W.

Photo: http://ahoy.tk-jk.net/macslog/BoxingtheCompas.html

Looking north, down the Vicdessos valley to the lowlands beyond. Note in particular the broad and relatively flat area upstream of Grotte de la Vache which would have provided excellent grazing for Ibex during the winter months, when the herbage in the mountains to the south was covered in snow.

Photo: Google Earth

Looking south, up the Vicdessos valley to the Pyrenees beyond. This view shows clearly the favoured position of Grotte de la Vache with good grazing for Ibex in winter, with north facing slopes in the mountains nearby, which would not have lost their snow even in summer, 13 000 years ago. The snow line at that time was at 1300 metres.

The toe of the Vicdessos glacier was certainly no more than three kilometres away during the Magdalenian, and may have been closer to Grotte de la Vache and Grotte de Niaux than that.

The two caves are approximately 500 metres apart, on opposite sides of the valley.

Photo: Google Earth

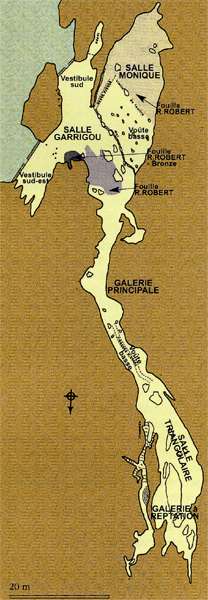

Plan of the Grotte de la Vache.

Plan by the caving club of Haut-Sabarthez, revised and completed by R. Gailli.

Photo: Gailli (2008)

Salle Triangulaire

The guide took us first to the Salle triangulaire. This is almost at the end of the cave, which is not a huge place. The name is apt because of the very flat and steeply angled left wall as you approach, which combined with the sloping though uneven right wall gives the impression of an old fashioned tent, or an attic, with a triangular roof section. The apex of the roof is about five or six metres above the floor of the cave, and the Salle triangulaire is about twenty or so metres long.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Recently discovered on the left, sloping flat side of the Salle Triangulaire, at 2.4 metres above the floor, are these digital sketches which it is believed are prehistoric. A large boulder was used to allow access to the wall.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Text: Translated and adapted from Gailli (2008) by Don Hitchcock

This panel is about 60 cm square, with classic but almost straight "macaroni" type marks, using four fingers of one hand, in a curving pattern downwards and to the right. On the right and above these, one finger has traced a multiple spiral, reminiscent of the head of a figure, but not interpretable as such.

It was only after electrification of the cave, with a spot light at an oblique angle, that these marks were discovered. They are invisible if one shines a light such as a hand held flashlight at the wall, which is why they were undiscovered for so long.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Text: Translated and adapted from Gailli (2008) by Don Hitchcock

Another area in the Salle Triangulaire, shown here, with markings of a similar nature is much less obvious, and it is not known what the marks signify.

Further, there is no way of discovering how old these traces are. They may be very old, or they may be relatively recent.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Text: Translated and adapted from Gailli (2008) by Don Hitchcock

At the end of the Salle triangulaire, beyond the pillars we can see the Galerie à Reptation, the Winding or Creeping Gallery.

So far as I am aware, this gallery is a sterile area with no wall markings. It is not accessible to the public, since the ceiling is so low. It gives access to some much smaller passages where one must crawl to proceed, but none of the passages goes very far into the rest of the hill.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

This is one of those passages, which ends in a blank wall. The whole floor of the cave is remarkably flat. There is an intermittent rain of fine particles from the ceiling of the cave, and when the cave occasionally gets water covering the floor, the clay and limestone particles settle out in a flat layer.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

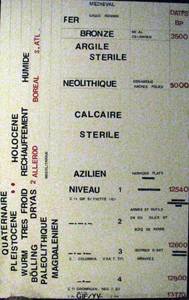

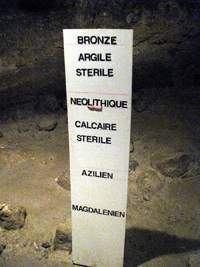

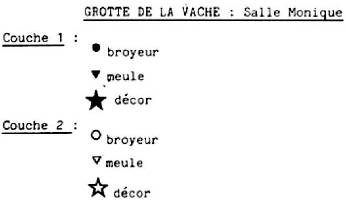

Table of the sediments in Grotte de la Vache.

In the Magdalenian, 13 000 years ago, this area was very cold indeed.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Panorama of the meeting room, the Salle Monique, at Grotte de La Vache. The cave would have been a relatively warm refuge from the rigours of the chase during the Magdalenian, in an alpine area subject to sudden changes of weather even today. The cave maintains a steady temperature of 13°C throughout the year.

The whole area was covered at the time of its modern discovery with a metre or more of sediments from the rain of very fine particles flaking off the roof over thirteen thousand years. The level of the original floor of the cave before excavation down to the Magdalenian level can be seen as a distinct line on the far wall of this room.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

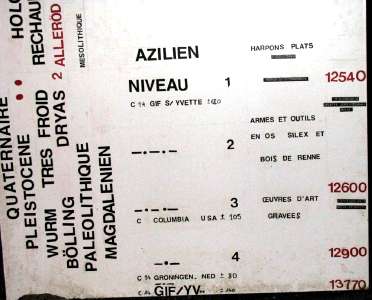

A simplified indication of the depth, type, and ages of sediments previously in the Salle Monique, before they were excavated by Romain Robert, after its discovery by his young daughter, Monique, in 1952.

Dating

The following dates are from Pailhaugue (1998)

Two carbon-14 dates on charcoal were performed by the laboratory of Groningue at the request of R. Robert:

Gr 2025: 12 540 ± 105 BP Layer II

Gr 2026: 12 850 ± 140 BP layer IV

A new dating performed at our request by the laboratory of Gif-sur-Yvette on a lot of bones confirmed the previous ones:

Gif. 7603: 12 800 ± 140 BP layer II

Recently, we have obtained dates produced by the particle accelerator laboratory in Gif-sur-Yvette:

Square 269, depth 109 cm: 13 490 ± 120 BP

Square 71, depth 59.5 cm: 13 770BP ± 140

Square 71 depth 115 cm: 13 650BP ± 130

Note that these dates agree very well with the dates for the paintings in Grotte Niaux just across the valley.

No artefacts apart from a bone needle have been found in the Grotte Niaux. There are no remains of meals or evidence of habitation there at all.

It would appear that Grotte Vache was used as a living area, and Niaux was used exclusively for artworks, by the same people.

Salle Monique. There are many hearths here with their stone surrounds still in place.

I could not help imagining the laughter, song and feasting that must have taken place during the time of its occupation. This would have been a magic place, secure from the howling, icy wind outside, where outer clothing could be removed, and long stories of bravery and treachery could be told around the campfires.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

This is a flint tool from the time of the occupation of the Grotte de la Vache. Good quality flint like this was sometimes carried hundreds of kilometres from the quarry where it was unearthed.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Tools from Grotte de la Vache.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Museum, Alliat, Ariège

This is a recent small dig in one corner of the Salle Monique near the entrance, which has turned up some interesting finds.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Many bones are easily identifiable, even in this photo. Some have been cracked open to extract the fat-rich marrow.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

These horns of a Bouquetin, or Ibex, were from a hunted and gutted animal, brought back to the cave otherwise entire. The faunal remains indicate (Pailhaugue,1998) that this was the normal procedure for the deposits analysed at La Salle Monique.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Ibex, border area Switzerland-Austria-Liechtenstein, 11th August 2008.

Photo: Wikimedia

Author: Nudelbraut

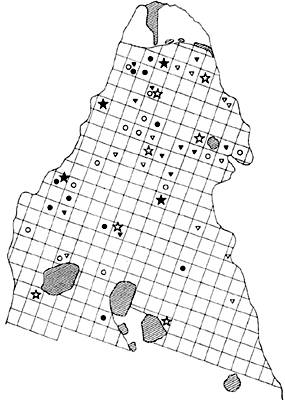

Plan of Salle Monique, showing the distribution of objects carrying traces of colouring agents such as iron oxide and manganese dioxide. All such colouring agents were associated with biotite, a black or dark green mineral of the mica group, found in igneous and metamorphic rocks. The biotite was added because it gave the paint more opacity, since it is one of the micas, and the tiny flakes reflect light back to the viewer.

Broyeur - pestle

Meule - mortar

Décor - decorated object

Photo: Pinçon et al (1989)

Os gravé figurant une frise de lions, a famous piece showing a line of cave lions with what might be construed as a happy expression!

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Os gravé figurant deux loups affrontés

Engraved bone depicting two wolves facing one another.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Os gravé figurant deux rennes se flairent, engraved bone showing two reindeer, one sniffing the other.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

As above, two reindeer in line. The artist has captured the animals with the eye of a hunter who has observed nature closely.

Photo: Delporte (1993)

Os gravé figurant des bouquetins de face et de profil, Engraved bone showing ibex in profile and face on.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

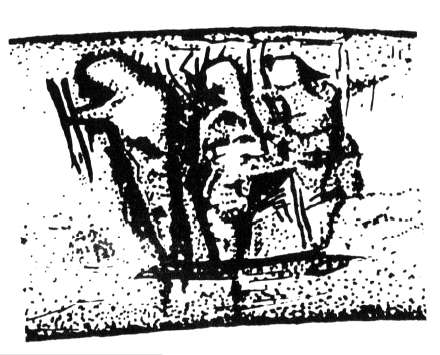

Ellipse gravée figurant deux silhouettes humaines et des signes, Engraved oval showing two human silhouttes and some symbols.

(note that these are very similar in form to the two women on the Isturitz plaque - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Bâton percé sculpté figurant une tête d'herbivore, spear straightener showing the head of a herbivore.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

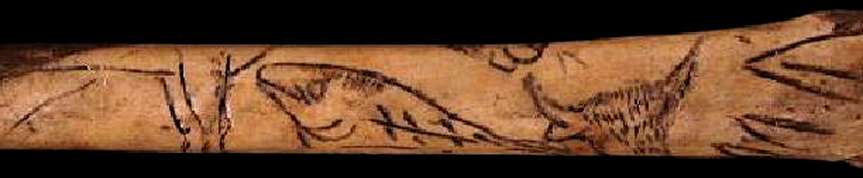

Os gravé figurant une biche et deux poissons.

Engraved bone depicting a doe and two fish.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Os gravé figurant deux chevaux se flairant. Engraved bone depicting two horses, one sniffing the other.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Os gravé figurant des bouquetins de profil. Engraved bone showing the profiles of several ibexes.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

A file of Ibex, as above. This is a very sophisticated work. Grotte de la Vache was home to some fine artists.

Photo: Delporte (1993)

Bâton percé sculpté figurant une chasse à l'aurochs. Spear straightener featuring the hunting of an aurochs.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Le bâton percé de la 'chasse à l'aurochs' provenant de la grotte de La Vache, en Ariège constitue donc un objet exceptionnel. Sculpté dans un bois de renne, il porte à son extrémité une tête animale en relief et en ronde-bosse, probablement une tête de bouquetin vue de haut, et sur sa longeur une scène de chasse en relief, opposant un aurochs à trois chasseurs. Le premier chasseur a le bras tendu et la tête penchée vers l'avant, peut-être dans une position de visée, les traits parallèles au bout du bras figurant alors des sagaies.French text above from the display at the Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye.

This spear straightener known as 'the aurochs hunt' which comes from la grotte de La Vache in Ariège is an exceptional object. Carved in reindeer antler, it has at one end an animal head in relief and in the round, probably an ibex head seen from above, and along its length is depicted a hunting scene in relief of three hunters pursuing an aurochs. The first hunter has his arm outstretched and head tilted forward, perhaps to see more clearly, while the parallel lines in his hand appear to be representations of spears.

This is a beautiful piece of work, with the Aurochs and the hunters done in bas relief, a most unusual technique.

An artist's impression of the hunters is at the left.

The hole in the piece indicates that this is a spear straightener, or bâton percé.

Photo: Delporte (1993)

Another version of the spear straightener.

Photo: http://www.arretetonchar.fr/

Os gravé figurant une frise de bisons. Carved bone depicting a line of bisons.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Os gravé figurant un bovidé et une tête de bouquetin. Engraved bone depicting an aurochs and the head of an ibex.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Os gravé figurant un aurochs.

Engraved bone depicting an aurochs (or bison).

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Os gravé figurant un aurochs.

Engraved bone depicting an aurochs (or bison).

Height 180 mm, width 79 mm, thickness 6 mm.

Photo: © RMN (National Archaeological Museum) - Thierry Le Mage

Source: http://www.photo.rmn.fr/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult&IID=2C6NU0TDPYG9

Bois de cervidé sculpté figurant un poisson, un cervidé et une tête d'oiseau. Deer antler sculpture showing a fish, a deer and the head of a bird.

This piece is known as 'the sceptre'.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Ellipse gravée figurant deux têtes de cervidés, un cheval et des signes. An oval shape depicting two deer heads, a horse and some symbols.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

An unusual aspect of some pieces found at the Grotte de la Vache is that they were not only carved, they were stained with both red and black pigments, which demonstrates that this was an intentional act.

Out of a total of 225 pieces, only 16 were coloured, consisting of spears and "chisels" or scrapers, made of deer antler. There were 39 mortars and 44 pestles used for grinding up the colours, and there were colouring agents on 371 flint tools. These objects were more numerous in beds one and two.

Text translated and adapted from: Pinçon et al (1989)

In the case of this "ellipse", or arc, above, the colour affects the entire surface of the piece, and is found in the incisions, as well as the cells of the spongiosa, the centre of the bone. The oxides in the incisions can be seen in the closeup (left).

(It appears to be a scraper or stretcher or burnisher used in the preparation of hides. Note the left hand end which has been very carefully shaped, and is highly polished from much use. This was obviously a highly valued tool of great sentimental value, evidenced from the care and skill of its shaping and decoration - Don)

Photo and text translated and adapted from: Pinçon et al (1989)

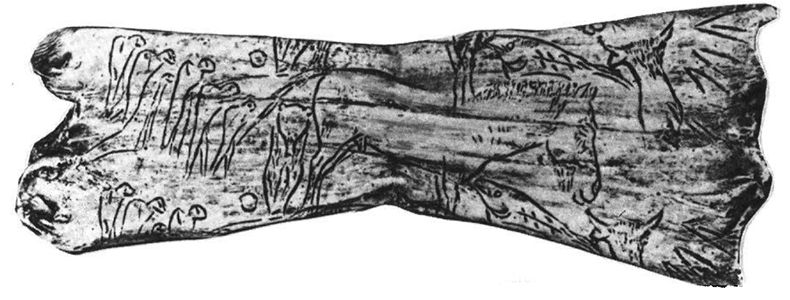

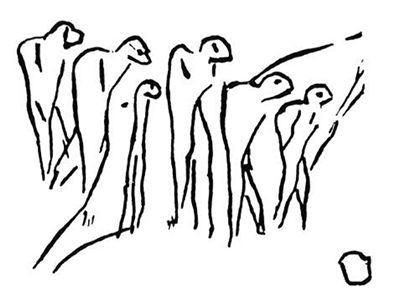

Os d'oiseau gravé figurant six humains, un ours de face, un cheval, un poisson et une tête de bison vue de face. An engraved bird bone depicting six people, a bear from the front, a horse, a fish, and the head of a bison seen from the front.

This is known as 'The Initiation Scene'.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Engraved bird bone

"La scène d'initiation"

Cat 455

Origin : La Vache cave, Ariège

Photo: © photo - Loïc Hamon, Musée des Antiquités nationales, Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Photo Source: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/app/eng/inits.htm

Initiation bone, with the carving unrolled.

Photo: Delporte (1993)

Group of people on the 'initiation' piece.

Photo: Delporte (1993)

Pebble showing much evidence of usage, notably those characteristic of pestles or grinders of oxide colouring agents such as iron and manganese oxides.

Photo and translated text adapted from: Pinçon et al (1989)

Two ibex facing each other. Again, a beautifully realised piece of art.

Photo: Delporte (1993)

(left): Magdalenian harpoon with one barb, from la grotte de La Vache, in reindeer antler.

Dimensions: 89 mm long, 8 mm wide, 6 mm thick.

Catalog: MAN83643

(centre): Magdalenian harpoon with two barbs on one side, from la grotte de La Vache, in reindeer antler.

Dimensions: 86 mm long, 10 mm wide, 6 mm thick.

Catalog: MAN83062.46

(right): Magdalenian harpoon with three barbs on one side, from la grotte de La Vache, in reindeer antler.

Dimensions: 110 mm long, 12 mm wide, 7 mm thick.

Catalog: MAN83641.VIC54

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: https://www.photo.rmn.fr

(left): Magdalenian one sided harpoon originally with four barbs, of which three remain, from la grotte de La Vache, in reindeer antler.

Dimensions according to the catalog: 139 mm long, 140 mm wide, 70 mm thick.

( Likely actual dimensions: 139 mm long, 14 mm wide, 7 mm thick - Don )

Catalog: MAN83642CXLIII C 62

(right): Magdalenian two sided harpoon with ten barbs, from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length 105 mm, width 14 mm, thickness 9 mm.

Catalog: MAN83640.C.40

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: https://www.photo.rmn.fr

(left): Magdalenian foëne or fish spear from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length 61 mm, width 19 mm, thickness 5 mm.

Catalog: MAN83641CLXC61

(right): Magdalenian foëne or fish spear from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length 71 mm, width 21 mm, thickness 8 mm.

Catalog: MAN83640.CXLIIIC43

These are points of reindeer antler which were attached to a long shaft, used for catching flatfish, particularly while wading in shallow waters. Its handle could be equipped with a cord, enabling the spear to be retrieved when thrown at a fish. In particular, foëne were often used for eel fishing, the extra points making it possible to catch these fish, which are slippery and difficult to catch otherwise.

It is speculated that they may have been used to take down birds as well.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: https://www.photo.rmn.fr

Additional text: Wikipedia

Magdalenian spear point with a trimmed base, from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length 96 mm, width 8 mm, thickness 7 mm.

Catalog: MAN83642

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: https://www.photo.rmn.fr

(left) Magdalenian spear point with a double bevel in reindeer antler from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length ? mm, width 9 mm, thickness 7 mm.

Catalog: MAN83642.XLID114

(right) Magdalenian spear point with a double bevel in reindeer antler from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length 76 mm, width 8 mm, thickness 6 mm.

Catalog: MAN83643.XXXVID124

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: https://www.photo.rmn.fr

(left): Magdalenian grooved bone from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length 74 mm, width 16 mm, thickness 7 mm.

Catalog: MAN83062.484

(right): Magdalenian eyed needle in bone from la grotte de La Vache.

Dimensions: length 36 mm, width 3 mm, thickness 2 mm.

Catalog: MAN83642.CCLR7

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: https://www.photo.rmn.fr

Magdalenian bone eyed needles from la grotte de la Vache.

(left): Dimensions: length 55 mm, width 3 mm, thickness 2 mm.

Catalog: MAN83640R71

(centre): Dimensions: length 46 mm, width 3 mm, thickness 2 mm.

Catalog: MAN83062.3

(right): Dimensions: length 31 mm, width 3 mm, thickness 2 mm.

Catalog: MAN83643CLXXR3

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: https://www.photo.rmn.fr

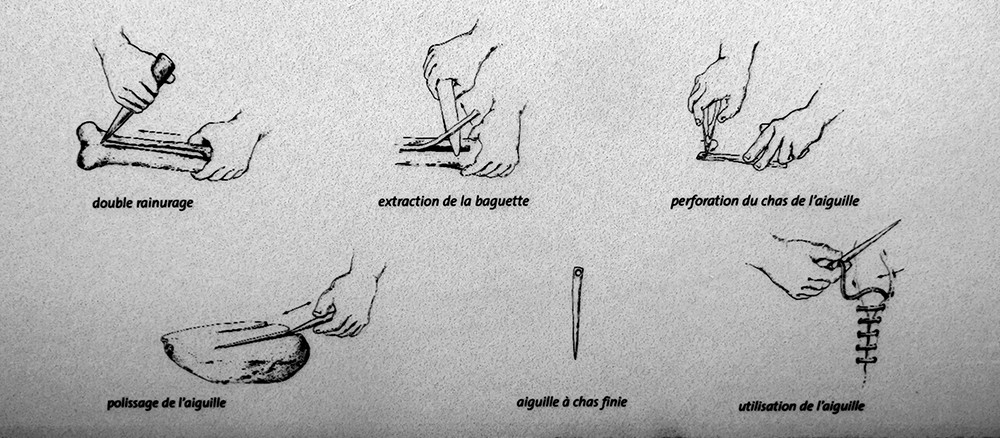

Making a needle

First, two long grooves were made in a suitable long bone using a burin, with two short grooves at either end, completing a long thin rectangle.

This was then split using a wedge or ciseau, to break open the grooves made in the hollow bone, and the rectangle was carefully levered out. This is why reindeer antler was rarely used for this purpose, since it was easier to make it from bone, which is hollow, and takes a very sharp point.

The eye was then put into the rectangular piece of bone at this point, while there was still plenty of 'meat' around the hole being made, and the needle was then carefully sanded and polished into shape.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: poster, artist unknown, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Text: Don Hitchcock

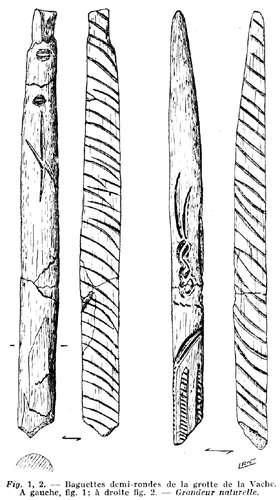

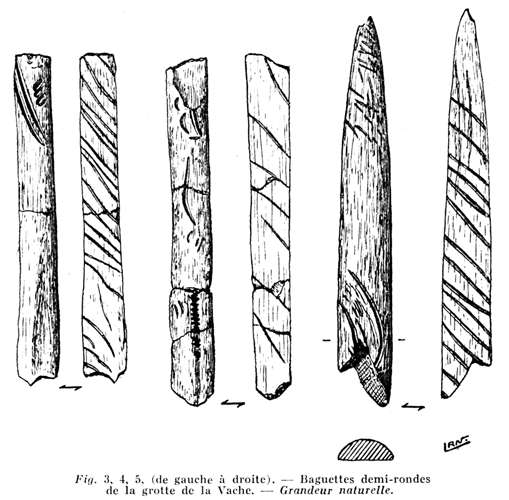

Baguettes demi-rondes from the Grotte de la Vache.

Note the carved decorations on the convex side, and the oblique grooves on the planar or slightly concave side.

The baguette demi-ronde on the right has what appears to be a stylised Ibex head carved into it.

Photo: Breuil et Robert (1951)

Baguettes demi-rondes from the Grotte de la Vache.

Photo: Breuil et Robert (1951)

Baguettes demi-rondes from the Grotte de la Vache.

Photo: Breuil et Robert (1951)

(As far as I can make out, baguette demi-rondes were fixed to a shaft, (somehow!) and the reason for the half round shape, i.e. round on one side, flat on the other, is that they were tied together around a flint (or bone or ivory) projectile point, with the flat sides against the point and each other, the round shape towards the outside.

Thus the two round sides made a roughly cylindrical shape, which could then be, say, inserted in a socket in the spear shaft and secured in some way. The end of the spear shaft could also have been whittled down to a tongue shape, flat on both sides, around which the two baguette demi-rondes were placed and secured with cord. If I was doing it, that's what I would try first. The darts weren't really of a large enough diameter to be able to carve a hole to accept the baguette demi-ronde. Harpoon shafts for fishing, however, were used more as thrusting spears as far as I can work out, so they could be of a much larger diameter, into which you could carve a socket.

Birch bark glue may have been used, and the glue would also have been used to strengthen the cords holding the two halves together. Birch bark glue is a very difficult glue to make, but the technique was well understood at that time.

The advantage is that if the flint is broken by impact with the ground or a bone, you can simply insert another flint head, attach it with cord or a leather thong, and you are ready to hunt again. You then only have to carry a few spear shafts and many light and easily packed flints when you go on a hunt, apart from the other things you need.

I emphasise that this is all conjecture on my part, I have been unable to get anything more than very unsatisfactory allusions to the technique.

However the idea of a fore-shaft is one that was used in a number of cases, and especially for harpoon heads. Methods were needed to attach bone or ivory harpoon heads to the shaft of the harpoon, and I've heard of sockets being used in that instance.

In the abstract of Pearson (1999) you will find this, in reference to north american hunting methods:

Based on the compiled information, a new hafting method for Clovis points is put forth that links the attributes of bi-beveled rods to a specific role within this system. This new hypothesis suggests that bi-beveled rods were tied facing each other around a Clovis point and a main shaft as part of composite clothes pin-like foreshafts.

The spears used are more properly referred to as darts, they were not the strong thrusting spear as used by, say, the Romans, but a long, thin, whippy piece of wood. The ability to bend is an integral part of why they are able to be thrown such long distances. The bend stores up energy which is released in the form of extra speed as it leaves the spear thrower, and the spear straightens.

- Don)

Dr Clark, Dr Sahly, Miss Boyl, Abbé Breuil, Romain Robert and F. Denjean at the entrance to the Grotte de la Vache (11th August 1958). Livre Préhistoire Ariégeoise 1985.

Photo and text translated from: http://www2.ac-toulouse.fr/eco-primaire-pradelet-tarascon/spip.php?article558

L’Abbé Breuil, undated photograph in the book Livre Préhistoire Ariégeoise (1985).

Photo: http://www2.ac-toulouse.fr/eco-primaire-pradelet-tarascon/spip.php?article558

| Composition of colouring agents used at Grotte de la Vache | ||

| Compound | Formula | Morphology |

| Calcite | CaCO3 | varnish or glaze, some micrometres |

| Black pigment | MnO2 | needle-like grains, five to twenty micrometres |

| Red pigment | Fe2O3 | grains and plates or scales, about five micrometres |

| Quartz | SiO2 | irregular grains, some micrometres |

| Biotite | Black mica, a ferro-magnesium compound | flakes |

Table adapted and translated from: Pinçon et al (1989)

| Colouring agents in various Paleolithic Caves | ||

| Cave | Red | Black |

| Niaux | wood charcoal | |

| Lascaux | Hematite, Goethite | Oxides of Manganese, wood charcoal |

| Altamira | Iron Oxides | Oxides of Manganese, wood charcoal |

| Quercy | Oxides of Manganese and Barium, wood charcoal | |

| La Vache | Oxides of iron, and biotite | Oxides of Manganese, and biotite |

Table adapted and translated from: Pinçon et al (1989)

| Percentages at Grotte de la Vache of various species in remains of animals eaten and as decorations | ||

| Species | Food | Figures |

| Reindeer | 3.85% | |

| Deer and other Cervids | 4.96% | 11.54% |

| Bovids | 0.24% | 16.67% |

| Chamois | 4.99% | |

| Ibex | 88.25% | 17.95% |

| Saiga Antelope | 2.56% | |

| Horse | 0.01% | 25.64% |

| Bear | 8.97% | |

| Wolf | 5.13% | |

| Lion | 6.41% | |

| Seal? | 1.28% | |

| Hare | 0.96% | |

Table adapted and translated from: Delporte (1993)

Human migration using DNA analysis

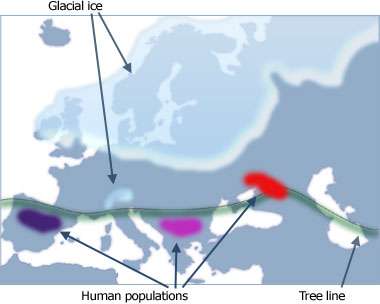

It is instructive to look at the groupings of DNA in modern human populations in order to discover where they originated from. During the glacial maximum about 20 000 ago, there were three main groups of anatomically modern humans in warmer climates, utilising the warmer temperatures in the Iberian (spanish) peninsula, the Balkans, and the area north-west of the Black Sea, the present day Ukraine.

This does not show that there were no humans between the tree line and the ice - there were. However there was a movement from these refugia in warmer climes to the productive lands of present day France, Germany, Hungary and so on as they came out of the grip of the worst of the ice age, and became more productive - Don

This image shows Palaeolithic Europe 18 000 years ago in the grip of the last ice age. Glacial ice 2km thick covers much of Northern Europe and the Alps. Sea levels are approx. 125m lower than today and the coastline differs slightly from the present day. For example, Britain and Ireland would have been connected to continental Europe (not shown on map).

The air would have been on average 10-12 degrees cooler and much more arid. In between the ice and the tree line, drought-tolerant grasses and loess dunes would have dominated the landscape.

The Neanderthals would have died out around 14 000 years ago leaving the nomadic hunter-gatherer Cro-Magnon (modern man) to pursue the animals of the time. Due to the cold and the need for food, the populations of the day waited the ice age out in the three locations shown on the map. These were the Iberian Peninsula, the Balkans and Ukraine.

These people were skilled in flint-knapping techniques and various tools such as end-scrapers for animal skins and burins for working wood and engraving were common. Cave painting using charcoal had been around for a couple of thousand years although at this time they were now more subtle than mere outline drawings. These artistic expressions are significant as it shows that people are able to obtain some leisure time. Whether this is ‘art for art’s sake’ or objects of ritual is not known.

Photo and text: http://www.dnaheritage.com/masterclass2.asp

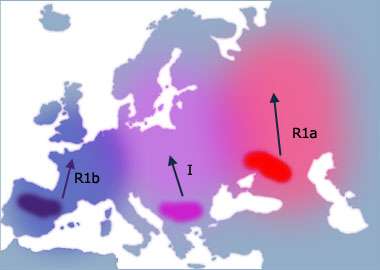

If we fast forward to 12 000 years ago as shown here, the ice has retreated and the land has become much more supportive to life. Many animal species have returned to inhabit the land, although the snake, harvest mouse and mole never made it as far as Ireland before the land bridges re-flooded (ever wondered why there are no snakes in Ireland?).

This map shows the spread of Haplogroups R1b, I and R1a (12nbsp;000 years ago).

Photo and text: http://www.dnaheritage.com/masterclass2.asp

The three groups of humans had taken refuge for so long that their DNA had naturally picked up mutations, and consequently can be defined into different haplogroups. As they spread from these refuges, Haplogroups R1b, I and R1a propagated across Europe.

- Haplogroup R1b is common on the western Atlantic coast as far as Scotland.

- Haplogroup I is common across central Europe and up into Scandinavia.

- Haplogroup R1a is common in eastern Europe and has also spread across into central Asia and as far as India and Pakistan.

These three major haplogroups account for approx 80% of Europe's present-day population.

(Readers who wish to follow this topic further, may be interested in http://www.roperld.com/HomoSapienEvents.htm -Don)

Text: http://www.dnaheritage.com/masterclass2.asp

From Wikipedia:

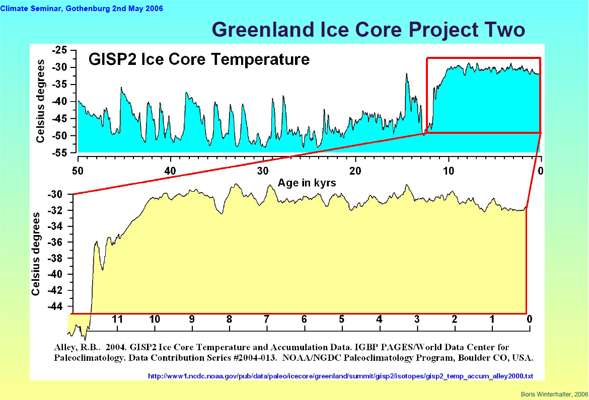

The Allerød period was a warm and moist global interstadial that occurred at the end of the last glacial period. The Allerød oscillation raised temperatures (in the northern Atlantic region to almost present-day levels), before they declined again in the succeeding Younger Dryas period, which was followed by the present interglacial period. The Greenland Oxygen isotope record shows the warming identified with the Allerød to be after about 14 100 BP and before about 12 900 BP.

(Note that this is the period during which La Grotte de la Vache was inhabited, and the paintings were created at Niaux Cave - a warm period before the cold of the Younger Dryas (12 800 to 11 500 years ago) which was the last gasp of the last ice age - Don)

Climate Seminar, Gothenburg 2nd May 2006

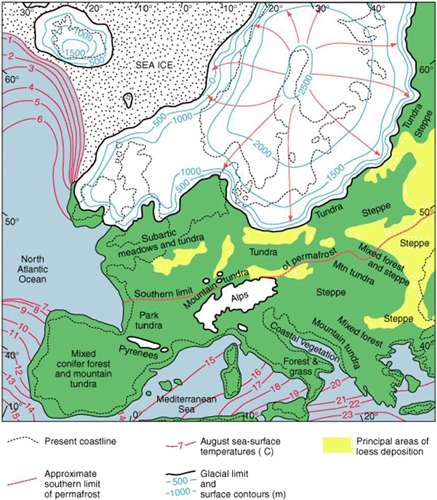

Continental Ice Sheet

Extent of the continental ice

sheet that covered northern

Europe 20 000 years ago, and

summer sea-surface

temperatures.

Central Europe had a climate

comparable to northern

Siberia, and southern Europe was forested.

About 10 000 years ago the ice

melted and the Holocene, a

period of pleasant climate,

began.

Photo and text adapted from: http://www.kolumbus.fi/boris.winterhalter/LEOprize/ClimateTalkOH.pdf

Climate Seminar, Gothenburg 2nd May 2006

This is a very useful graph for determining relative temperatures over the last 50 000 years, using ice core data as a proxy for global temperatures.

Photo: http://www.kolumbus.fi/boris.winterhalter/LEOprize/ClimateTalkOH.pdf

When I arrived, I found that there was a considerable wait before the next tour, so I occupied my time by investigating some side walks I had seen on the way in. These were very interesting.

In particular, I was fascinated by the fortified cave known as "Spoulga d'Alliat", about one hundred metres from the grotte de la Vache. It served as a refuge during the war of the Albigenses.

The fortification can now be accessed only by rope. At the time it was in use, it would have had rope ladders or light wooden ladders which could be pulled up after everyone was safe in the fortification. They would have needed a lot of food, water and other supplies if there had been an extended occupation of the area by enemy forces, and the safety of the occupants would have depended on their location being secret. An occupying army could have soon breached the defences of this little place of refuge, if only by seige.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Text below adapted from Wikipedia:

The Albigensian Crusade or Cathar Crusade (1209–1229) was a 20-year military campaign initiated by the Catholic Church to eliminate the Cathar heresy in Languedoc. Pope Innocent III declared a crusade against Languedoc, offering the lands of the schismatics to any French nobleman willing to take up arms. The violence led to France's acquisition of lands with closer cultural and linguistic ties to Catalonia. An estimated 200 000 to 1 000 000 people were massacred during the crusade.

Sign pointing to Grottes des Fées (Fairies Cave)

Grottes des Fées (Fairies Cave)

The European wall lizard, Podarcis muralis, is a small lizard whose scales are highly variable in colour and pattern.

This one moved around very quickly, and was difficult to photograph. It is a little bit unusual in that it has a pronounced blue/green colour, whereas most are shades of brown.

They are common in France, and grow to about 15 cm to 20 cm long, of which more than half is tail.

They can live for seven years, and eat insects and other invertebrates, and are themselves hunted by snakes.

Grottes des Fées (Fairies Cave)

References

- Breuil, H., Robert R., 1951: Les baguettes demi-rondes de la grotte de la Vache (Ariège). Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, 1951, tome 48, No. 9-10. pp. 453-457

- Delporte, H. , 1993: L'art mobilier de la Grotte de la Vache : premier essai de vue générale, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, Année 1993, Volume 90, Numéro 2 p. 131 - 136

- Gailli, R. , 2008: La Grotte Préhistorique de la Vache, Éditions Larrey CDL, 2008. ISBN-10: 2-908622-05-X ISBN-13: 978-2-908622-05-8

- Pailhaugue, N. , 1998: Faune et saisons d'occupation de la salle Monique au Magdalénien Pyrénéen, Grotte de la Vache (Alliat, Ariège, France), Quaternaire Volume 9, Numéro 4, 1998. pp. 385-400

- Pearson, G., 1999: North American Paleoindian Bi-Beveled Bone and Ivory Rods: A New Interpretation, North American Archaeologist, Volume 20, Number 2 / 1999 pp 81 - 103

- Pinçon, G., Walter Ph., Menu, M., Buisson D., 1989: Les objets colorés du Paléolithique supérieur : cas de la grotte de La Vache (Ariège), Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, Année 1989, Volume 86, Numéro 6 p. 183 - 192

Niaux Cave, or la Grotte de Niaux is one of the most famous prehistoric caves in Europe. It lies in the northern foothills of the Pyrenees, and is located in Ariège, in the valley of Vicdessos, across the valley from the smaller Grotte de la Vache, in an area rich with prehistoric sites. The huge cave entrance, 55 metres high and 50 metres wide, is at 678 metres above sea level. There are more than two kilometres of galleries, with a hundred or more superb paintings from Magdalenian times, most of which are in the famous 'Salon Noir', 800 metres from the entrance. Many of the paintings are done in the classic style of the Magdalenian, outlined in black or red pigment, mostly haematite or manganese dioxide respectively.

Niaux Cave, or la Grotte de Niaux is one of the most famous prehistoric caves in Europe. It lies in the northern foothills of the Pyrenees, and is located in Ariège, in the valley of Vicdessos, across the valley from the smaller Grotte de la Vache, in an area rich with prehistoric sites. The huge cave entrance, 55 metres high and 50 metres wide, is at 678 metres above sea level. There are more than two kilometres of galleries, with a hundred or more superb paintings from Magdalenian times, most of which are in the famous 'Salon Noir', 800 metres from the entrance. Many of the paintings are done in the classic style of the Magdalenian, outlined in black or red pigment, mostly haematite or manganese dioxide respectively.