Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

Ice Age Hunters become farmers: Schleswig-Holstein on the way to the Neolithic

An exhibition at the Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Towards the end of the ice age there was a short cold period when the glaciers advanced once more, but soon they began their final retreat, and the ice age was over.

The surface of this glacier just a few hundred years ago was hundreds of metres above the bare gravel surface from which I took this photo, and reached most of the way up the valley walls.

Photo: Franz Josef Glacier, NZ, Don Hitchcock 2007

Credits

A superb exhibition such as this depends on the people who put it together:

Scientific Responsibility: Jürgen Hoika, in collaboration with Klaus Bokelmann, Claus v. Carnap-Bornheim, Waller Dörfler, Pieter M. Grootes, Sönke Hartz, Dirk Heinrich, Helmut Kroll, Jutta Maurers-Balke, and lnge Sehröder

Exhibition Design: Hans-Joachim Mocka

Scenic design, models, replicas: Harm Paulsen

Graphic Design: Hans-Joachim Mocka, in collaboration with Atelier und Werkstatt Bokelmann, Flemming Bau, Reinhard Kühn, and Jörg Murawski

Digital Printing: CLC PrePress GmbH, Flansburg, EI Mundo, Süderbrarup

Photography: Claudia Franz, in collaboration with Mira Burgund and Sven Heinrich

Cinematography: Homann und Canham, Film · Ton · Installation, Hamburg

Catalogue, conservation, installation: Wulf-Dieter Freese, Ralner Hinriksen, Wolfgang Lage, Klaus Niendorf, Harm Paulsen, Otto Siebken, lnga Sommerfeld, Gerhard Stawlnoga, lngrid Ulbricht

In cooperation with: Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Institut für Haustierkunde, Institut für Anthropologie, Leibniz-Labor für Altersbestimmungen und Isotopenforschung, Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Universität zu Köln, Klaus-Peter Thom, Schleswig

With friendly support from: ARD-Studlo London, Dr. Joachim Wagner, Forstamt Schleswlg, Barnd Friedrichsdorf, Norddeutscher Rundfunk, ARD-Aktuall, Martina Hammerich, Hamburg, Staatliche Försterei ldstedt, Hans-Jürgen Malende, Gerd Walther, Fahrdorf-Loopstedt

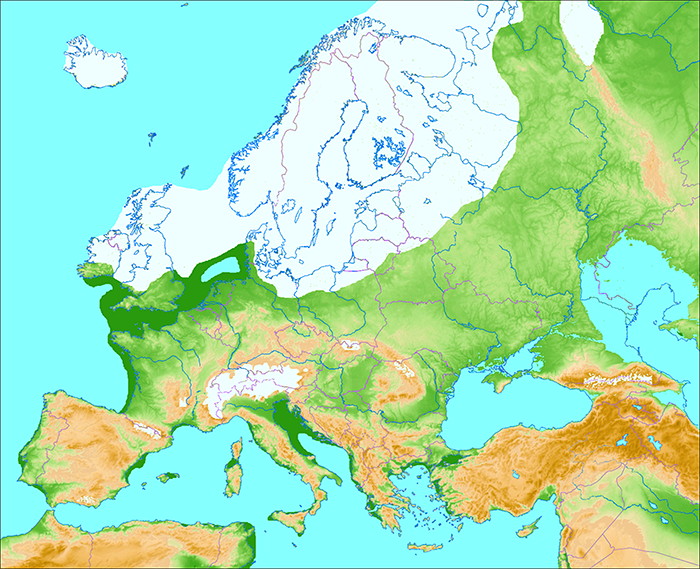

The End of the Last Ice Age - and What Came Next

Map showing the maximum extent of the ice in Europe during its last glaciation, called in northern Europe the Weichselian Glaciation, and in the Alpine Region the Würm Glaciation. The maximum shown here occurred at 20 000 BP.

The extent of glaciation, sea and lakes have been painted freehand according to www.diercke.de: Würm-/Weichseleiszeit (letzte Eiszeit) - Vergletscherung and File:Map of Alpine Glaciations.png

Source File: Europe topography map.png, 2 April 2006 by San Jose, based on the Generic Mapping Tools and ETOPO2

Photo: Ulamm

Permission: GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation

Source and text: Wikipedia

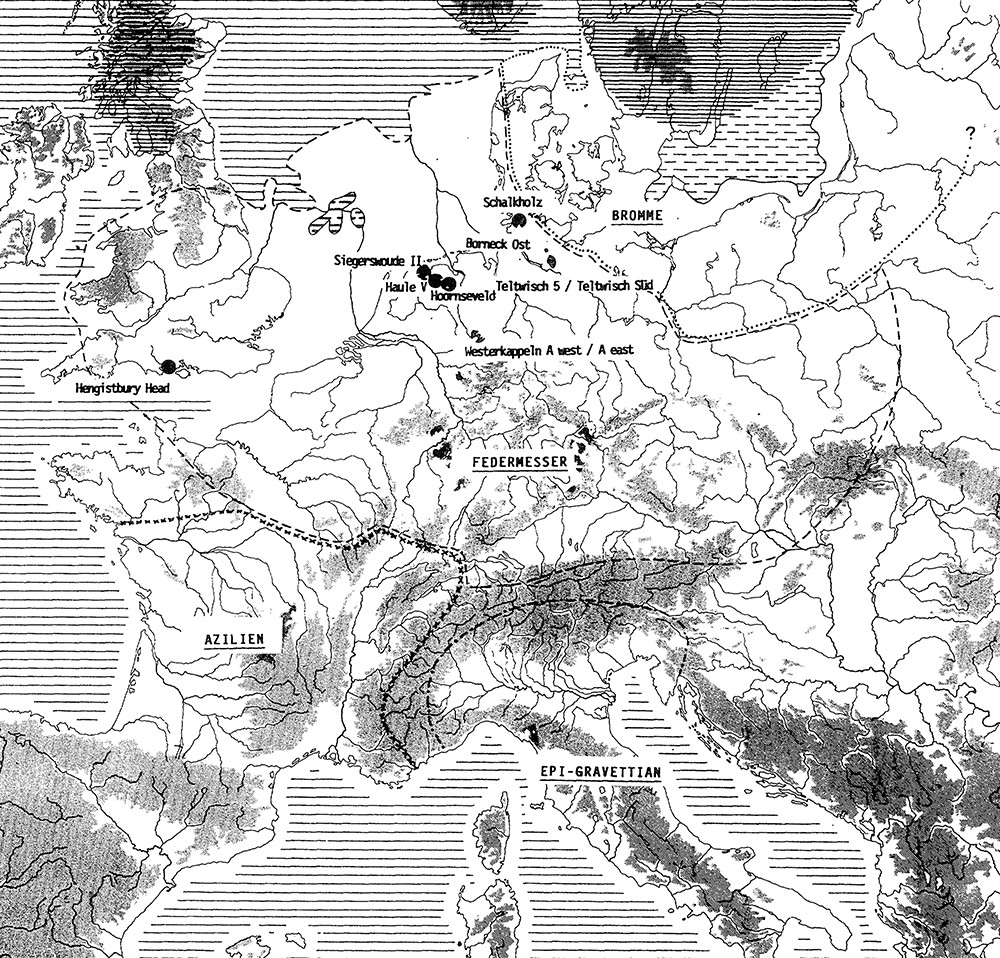

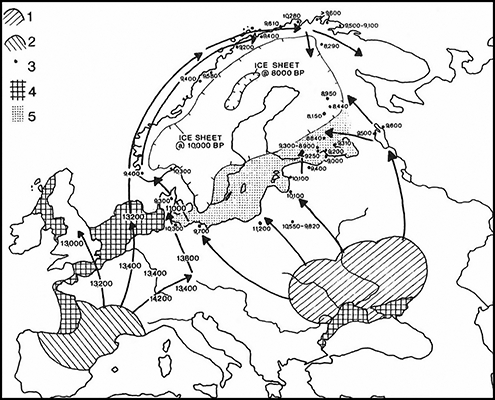

Routes taken for the reoccupation of land in Europe after the ice age.

1. Recolonisation of Eastern Europe.

2. Recolonisation of southwestern Europe.

3. Oldest regional settlement sites.

4. Shoreline towards the end of the ice age.

5. Yoldia Lake (before the breakthrough of the Baltic into the North Sea).

Photo: Haarmann (2016)

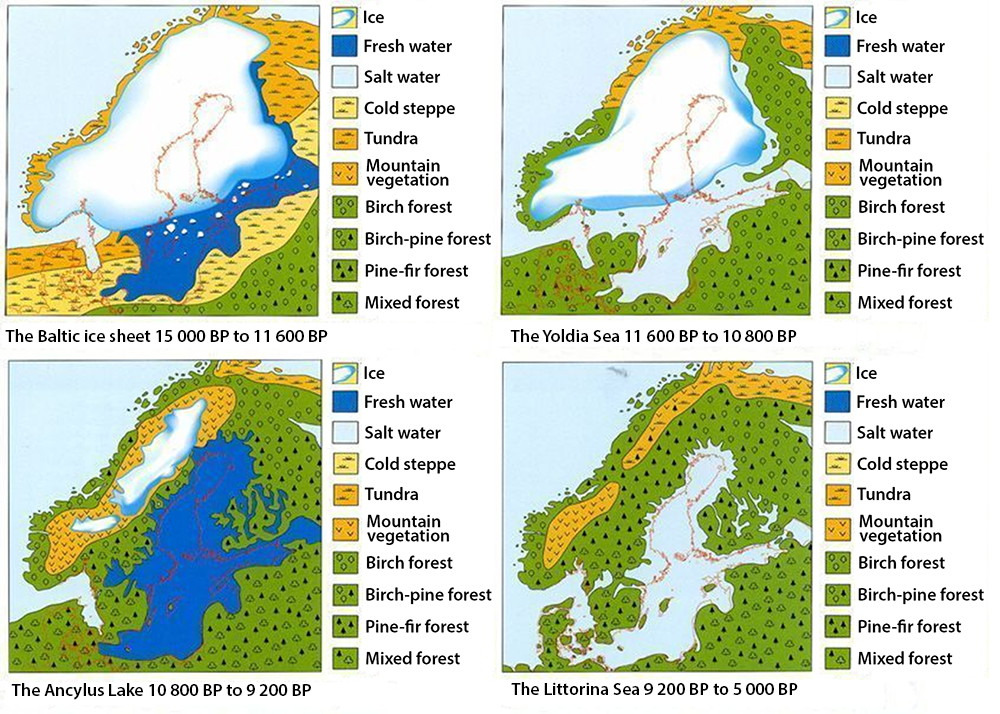

( note that the dates given here are only approximate, and different sources give slightly different dates for the various stages - Don )

Top left: The Baltic Ice Sheet, 15 000 BP to 11 600 BP, known in Danish as Den Baltiske Issø, The Baltic Island. Beside it and created by it was the Baltic ice lake, which was a large freshwater lake and predecessor to the Baltic Sea. It was created when the inland ice sheet gradually began to retreat to the north, and a freshwater reservoir was formed in the southern part of the Baltic Sea basin. The lake was dammed partly by the surrounding lands and partly by the inland Baltic Ice Sheet, was higher than the ocean, and had icebergs drifting on its surface.

Top right: The Yoldia Sea, 11 600 BP to 10 800 BP, dated by material from ancient sediments, shore lines, and from clay-varve chronology.

The Yoldia Sea is the name given by geologists to a variable brackish-water stage in the Baltic Sea basin that prevailed after the Baltic ice lake was drained to sea level. The name derives from the bivalve, Yoldia arctica, now known as Portlandia arctica, which requires cold saline water. Its presence indicates the middle phase of the Yoldia Sea, when saline water poured into the Baltic, before the acceleration of glacial melting.

Bottom left: The Ancylus Lake, 10 800 BP to 9 200 BP, which replaced the Yoldia Sea after the latter had been severed from its saline intake across a seaway along the Central Swedish lowland, roughly between Gothenburg and Stockholm. The cutoff was the result of isostatic rise, itself because of the removal by melting of the weight of several kilometres thickness of ice, being faster than the concurrent post-glacial sea level rise. In 1887 Henrik Munthe was the first geologist to draw the conclusion that the Baltic Sea must once have been a freshwater lake, after finding fossils of the fresh water snail Ancylus fluviatilis in sediments.

Bottom right: The Littorina Sea, 9 200 BP to 5 000 BP replaced the Ancylus lake when rising sea levels began to break through the Dana River valley. This transformation was gradual, and the salt-water that began to enter the lake resulted in episodic brackish water pulses. The proper end of the Ancylus Lake came however around 7 800 BP – 7 200 BP when the Øresund, or the Sound, the strait which forms the Danish–Swedish border, was completely breached by the sea, causing a massive inflow of salt-water. The Littorina Sea is named after the common periwinkle Littorina littorea, then a prevailing mollusc in the Baltic Sea, which indicates that the water was saline.

Source and text: http://www.dandebat.dk/eng-dk-historie5.htm

Additional text: Wikipedia, Wikivisually

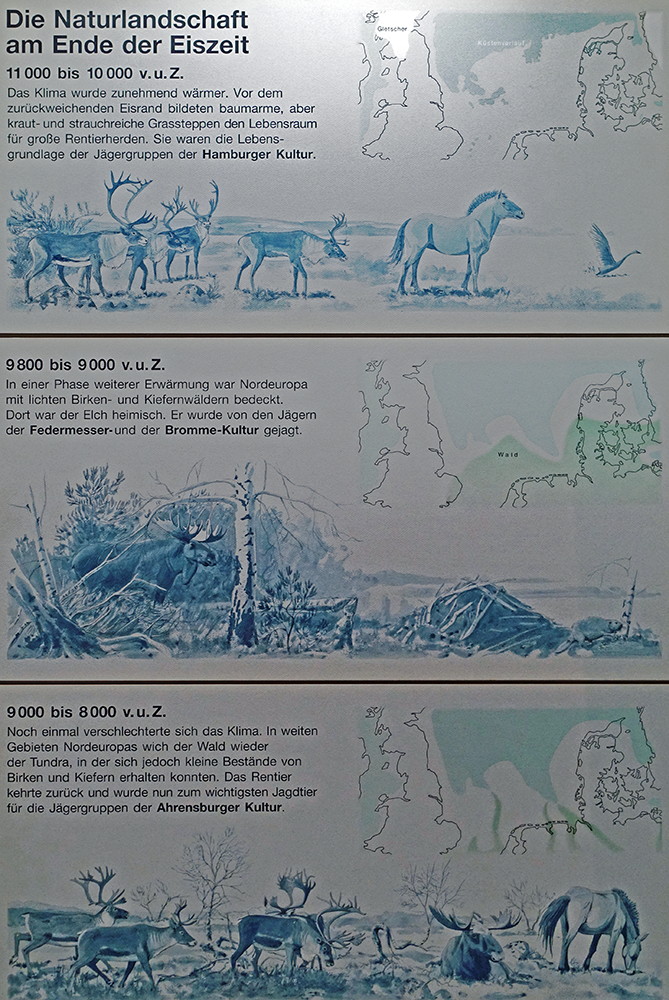

The natural landscape at the end of the ice age

Hamburg culture

13 000 BP to 12 000 BP

The climate became increasingly warm. In front of the receding ice edge, tree-poor, but herbaceous and shrubby grassy steppes formed the habitat for large reindeer and horse herds. They meant life for the hunter groups of the Hamburg culture.

Federmesser and Bromme cultures

11 800 BP to 11 000 BP

In a period of further warming, northern Europe was covered with sparse birch and pine forests.

Now the moose was at home, in forested areas where there was snow cover in the winter, and there were nearby lakes, bogs, swamps, streams and ponds. They were stalked by the hunters of the Federmesser and Bromme cultures.

Ahrensburg culture

13 000 BP to 12 000 BP

Once again the climate worsened with the onset of the Younger Dryas, the last cold snap of the Ice Age. In many areas of northern Europe, the forest retreated to the tundra, where small groups of birch and pine trees could be found. The reindeer returned and became the most important prey for the hunting groups of the Ahrensburg culture.

The Ahrensburg culture was a late Upper Palaeolithic nomadic hunter culture during the Younger Dryas, the last spell of cold at the end of the Weichsel glaciation resulting in deforestation and the formation of a tundra with bushy arctic white birch and rowan.

( The Federmesser (literally, feather knife) culture is named after a characteristic small knife, dubbed in English a penknife. Both terms refer to a small knife used to cut a pen from, typically, a goose quill. In common English usage it now means a small sharp knife which folds into its handle, kept in the pocket, sometimes called a pocket knife in fact, and used for minor tasks, though few users of the term now would be aware of its etymology.

The Bromme culture is named after a settlement at Bromme on western Zealand, and it is known from several settlements in Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein - Don )

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Wikipedia

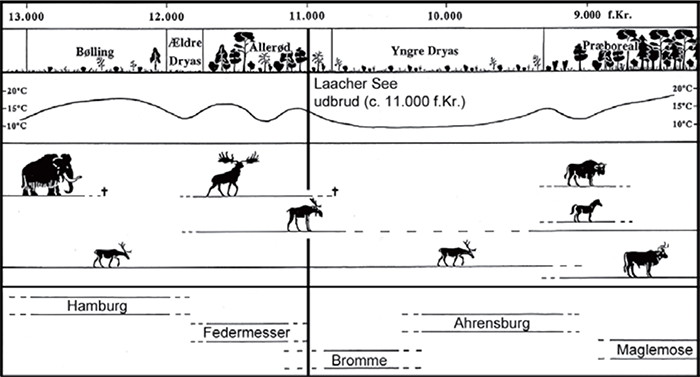

The changes in average temperature, flora and fauna during the Late Glacial in Southern Scandinavia.

The Laacher See eruption occurred around 13 000 BP and acts as a useful chronostratigraphic marker for this time.

Photo and text: Riede et al. (2011)

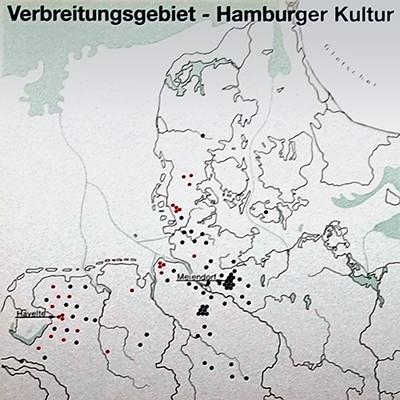

Hamburg culture

13 000 BP to 12 000 BP

Hamburg culture

Map showing sites of the Hamburg culture.

( Black dots indicate sites where 'classic' Hamburgian shouldered points were found, red dots indicate sites where the dominant point was the Havelte shouldered point, see below - Don )

Among the finds from the reindeer hunters' camps, flint tools predominate. The original hafts of wood, bone or antler are usually gone.

The characteristic stone implements were made of blades: shouldered points used as arrow or spear points, scrapers made on a blade for processing fur, borers and burins for the working of wood, antlers or bones.

Suitable flint was often found in the vicinity of the camps.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

The Hamburg culture or Hamburgian was a Late Upper Paleolithic culture of reindeer hunters in northwestern Europe during the last part of the Weichsel Glaciation beginning during the Bölling interstadial. Sites are found close to the ice caps of the time.Text above: Wikipedia

The Hamburg Culture has been identified at many places, for example, the settlement at Meiendorf and Ahrensburg north of Hamburg, Germany. It is characterised by shouldered points and borers, which were also used as burins when working with antler. In later periods tanged Havelte-type points appear, sometimes described as most of all a northwestern phenomenon.

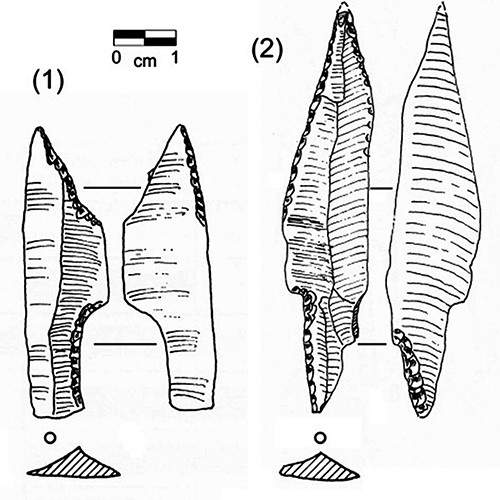

Hamburg culture

1. a 'classic' Hamburgian shouldered point

2. Havelte shouldered point.

Modified from Tromnau (1975b)

Source: Riede (2010)

Hamburg culture

Kerbspitzen / notched edge points / shouldered points / flint blades with a tang, typical of the Hamburgian culture.

Some points in this image are of the classic Hamburgian style, whilst others are those known as Havelte shouldered points.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Don Hitchcock

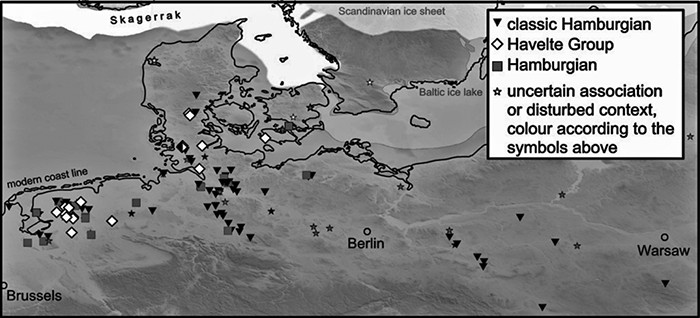

Hamburg culture

Distribution map of classic Hamburgian, Havelte Group and Hamburgian sites on the North European Plain at the beginning of the Lateglacial Interstadial.

Source and text: Grimm, Weber (2009)

Hamburg culture

Burins.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Hamburg culture

Double ended tools.

Stichel - burin, Kratzer - scraper, Zinken - awl or drill.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Hamburg culture

Scrapers.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

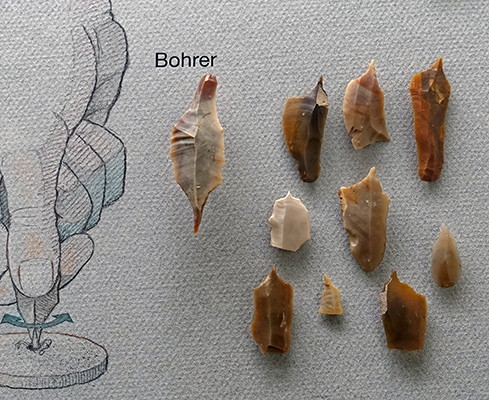

Hamburg culture

Awls.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Hamburg culture

Drills.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Hamburg culture

Tools of unknown function.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

The Bølling-Allerød interstadial

14 700 BP to 12 700 BP

The Bølling-Allerød interstadial was an abrupt warm and moist interstadial period that occurred during the final stages of the last glacial period. This warm period ran from circa 14 700 to 12 700 BP. It began with the end of the cold period known as the Oldest Dryas, and ended abruptly with the onset of the Younger Dryas, a cold period that reduced temperatures back to near-glacial levels within a decade.Text above: Wikipedia

In some regions, a cold period known as the Older Dryas can be detected in the middle of the Bølling-Allerød interstadial. In these regions the period is divided into the Bølling oscillation, which peaked around 14 500 BP, and the Allerød oscillation, which peaked closer to 13 000 BP.

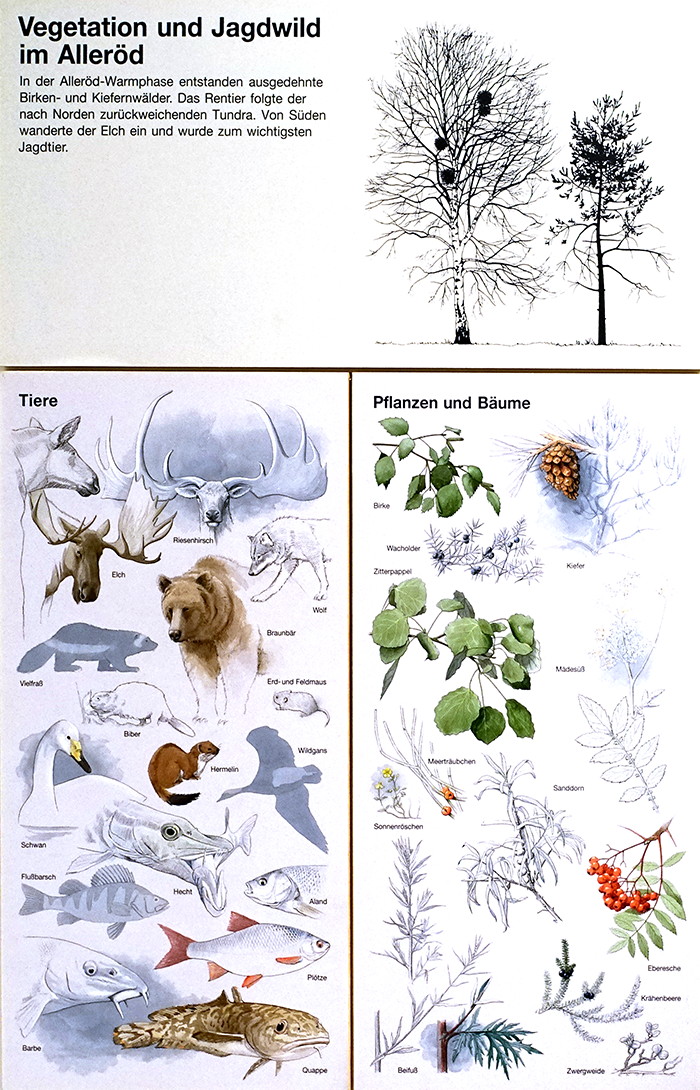

The Allerød Period

Vegetation and game hunted in the Allerød.

In the Allerød warm phase, extensive birch and pine forests were created. The reindeer followed the tundra, retreating to the north. Moose migrated from the south and became the most important hunting animal.

Fauna:

Megaloceros, Giant deer or Irish elk.

Moose.

Wolf.

Brown bear.

Wolverine

Beaver.

Field vole and Fieldmouse.

Ermine.

Wild geese.

Swan.

Pike.

Aland, Leuciscus idus, a type of carp.

Perch.

Roach.

Barbel.

Burbot, or freshwater ling.

Flora:

Birch.

Juniper.

Pine.

Aspen.

Meadowsweet.

Meerträubchen, Swiss Meydar.

Sea buckthorn.

Helianthemum, sunrose.

Rowan.

Crowberry.

Mugwort.

Dwarf willow.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser and Bromme Cultures

11 800 BP to 11 000 BP

The Federmesser and Bromme cultures were Hunting cultures of the Bølling-Allerød interstadial, an abrupt warm and moist period at the end of the Oldest Dryas cold period.

During the Bølling-Allerød warm phase, two cultures overlapped in Schleswig-Holstein, the South Scandinavian Bromme culture and the penknife culture of northern Germany. Both cultures are distinguished by characteristic flint tools, which are believed to indicate different hunting techniques.

The Final Palaeolithic cultural geography of the Allerød according to Newell & Constandse-Westermann (1996).

In their interesting and innovative analytical approach the Bromme culture is imbued with not only territorial and economic but also linguistic and ethnic significance ( Niekus, 1995).

Photo and text: Riede (2017)

Federmesser culture

Federmesser, after which the culture is named. These are small backed knives named after their similarity in shape and size to 'feather knives' or 'quill knives' or 'pen knives' which were used in much later times to cut a sharp point on (typically) a goose quill, which was then dipped in ink, and used for writing on parchment or paper.

Photo and text: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and identification: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser culture

Blades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser culture

Burins.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser culture

Burin spalls.

( these were often used as tools in their own right rather than being thrown away - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

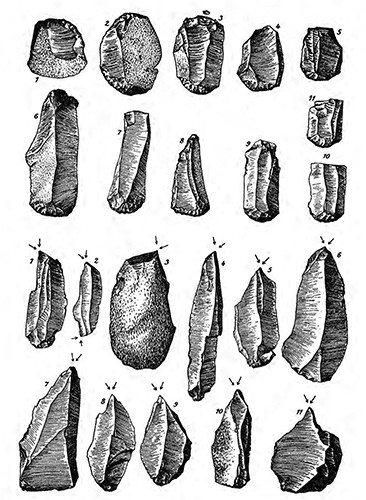

Federmesser culture

Cores or nuclei.

( the remainder of a piece of flint after as many tools as possible have been struck from it - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser culture

Scrapers.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser culture

Tools of unknown function.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser culture

Moose bone broken open for marrow extraction.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Federmesser culture

Antler and bone were scored by burins to decorate or split them into more suitable dimensions for tools.

In these two examples, the object of the exercise was for decoration.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

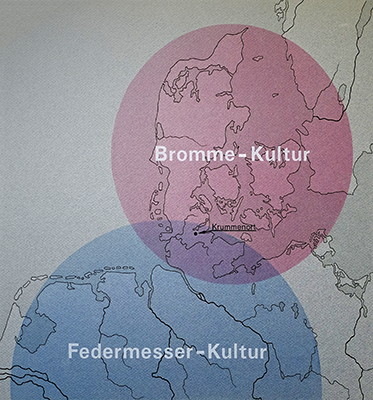

Map of the Federmesser and Bromme cultures in the Schleswig-Holstein general area.

The Federmesser and Bromme cultures overlapped somewhat, in both location and time, but with the Bromme culture starting (and ending) about 1000 years later than the Federmesser.

It may be that the more northerly Bromme culture developed as new lands opened up with the warming of the northern parts of the range.

Photo and explanatory text: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source for map and identification: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

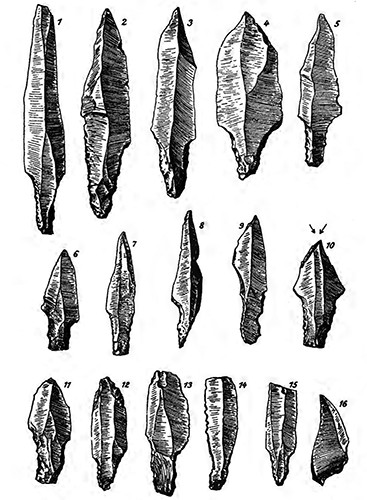

Bromme culture

Key types.

Bromme point, scraper, and burin.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

Bromme Point, and two Federmesser.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

(left) Bromme Points.

(right) Bromme scrapers and burins.

Photo: 'after Aarbøger 1946', de MoIyn (1954)

Bromme culture

Left to right: Federmesser (quill knife), scraper, and burin.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

Scraper.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

Burins.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

Retouched flakes.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

Blades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

Blades.

( note that the centre blade in this group of three has been retouched to form an end scraper, or grattoir. - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Bromme culture

Blades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

13 000 BP to 12 000 BP

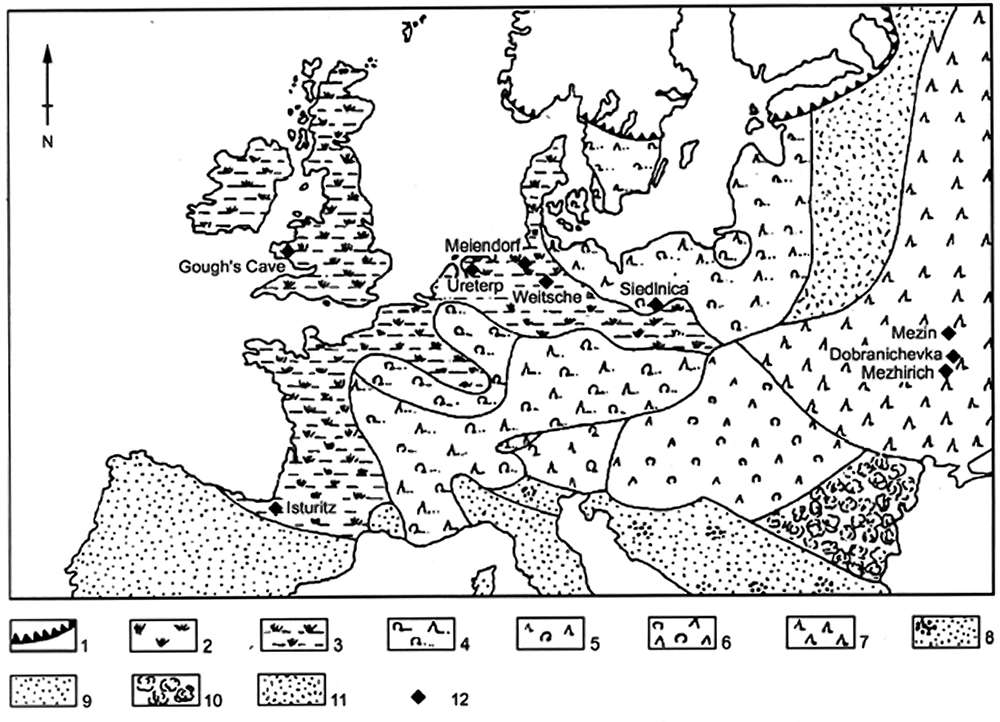

Map of the vegetation in Europe between 13 000 BP and 12 000 BP.

1 - Ice sheet

2 - Tundra

3 - Tundra 'xeric' variant (i.e. dry tundra)

4 - Birch-Pine forest

5 - Mixed forest

6 - Northern mixed conifer-deciduous forest

7 - Spruce dominated forest

8 - Steppe with Gramineae (now called Poaceae)

9 - Steppe (i.e. vast semi-arid grass-covered plain, as found in southeast Europe, Siberia, and central North America)

10 - Mixed-deciduous forest

11 - Mixed forest

12 - Sites with amber artefacts

Photo: Burdukeiwicz (1999)

Locations of Ahrensburg sites in the Schleswig-Holstein area.

( the important site of Stellmoor, where the Ahrensburger Tunnel Valley (see below) was situated, is marked on this map - Don )

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

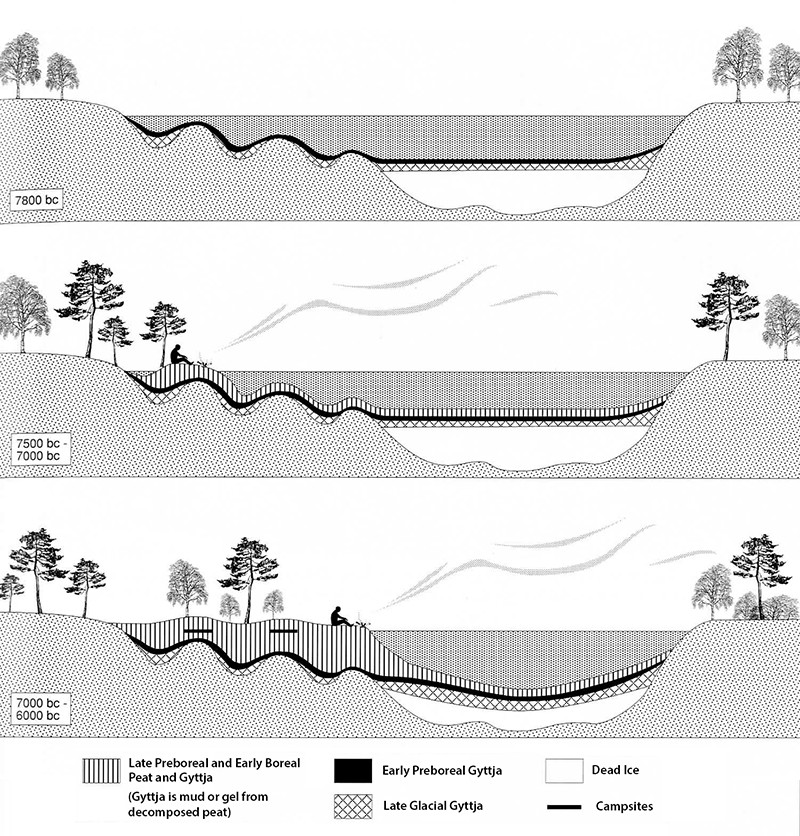

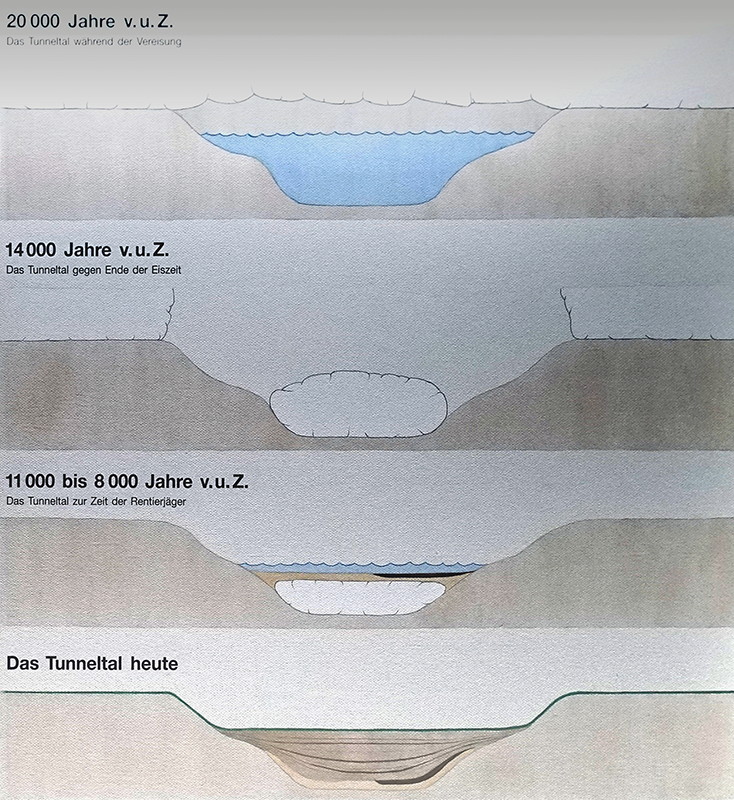

The Ahrensburg Tunnel Valley

Under the glaciers of the last ice age, meltwater carved out wide tunnels beneath the ice.

( This is happening in glacial valleys today as the glaciers melt, see photos below. Eventually the ice, being unsupported, collapses into the tunnel, and it is then covered by sediments carried by the shallow stream which now passes over the collapsed ice - Don )

Thus, although the glaciers eventually thawed completely, large blocks of ice, called dead ice, remained in low-lying areas under the sediments, and were protected from melting to some extent by these sediments.

The Ahrensburger Tunnel valley had to be crossed by migrating reindeer herds, and thus became a favoured area for the hunters of the Hamburg and the Ahrensburger culture.

The hunters' stations at Meiendorf and Stellmoor lay on the bank of a lake that had formed over the very slowly melting dead ice. In this lake, the bones and antlers of killed reindeer thrown into the lake have been well preserved because of the exclusion of air.

( the archaeological deposits are shown in black in the lower two panels of this painting - Don )

With the inevitable complete melting of the dead ice, the layers sank by several metres. Thus the discovery remained preserved until today.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Diorama of the hunting station at the tunnel valley.

Photo and text: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

This photograph shows clearly the way that the reindeer remains were preserved by the anaerobic conditions in the lake, and the swift burial of the objects.

Here we may also see the way that the originally horizontal deposits were tilted by the eventual melting of the dead ice, and the resultant collapse of the sediments into the void created.

Rephotography and additional text: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Meltwater pouring out from a tunnel beneath the Franz Josef Glacier in New Zealand.

Note the grey colour of the water from the rock flour suspended in it, made when the glacier grinds across its bed.

Photo and text: Don Hitchcock 2007

Left: Climbing dead ice in order to reach the active toe of the Fox Glacier in New Zealand.

Right: The toe of Fox Glacier. At this time, 2007, the glacier was advancing, temporarily and paradoxically, because of global warming.

Rising temperatures in the Tasman Sea to the west and the resulting increase in evaporation meant an increase of precipitation on the Southern Alps, which fell as snow, making the snow budget positive - the snow that fell more than replaced the ice that melted at the toe of the glacier.

By the following year, 2008, melting again got the upper hand despite the increased snowfall, and the glacier is now in rapid retreat, such that views and climbs like this are no longer possible, except by helicopter, since the glacier has retreated far up the valley.

Photo and text: Don Hitchcock 2007

The active toe of the Fox Glacier shown here (the low wall of fissured ice in the background of this image, reduced to just a few metres in thickness, and much further back up the valley in the scant six years from when I saw it last, and by then but a sad remnant of its former glory) is still connected to the rest of the glacier.

In the foreground of this image is dead ice, partially covered with sand, gravel, and rocks.

It is called dead ice, since it is no longer connected with the (moving) glacier proper, which is, in this case, like most others in the world, in retreat because of global warming. This shot, six years later, is taken a considerable distance further up the valley than the shots above, because of the retreat of the glacier.

The guides predicted at the time that in five years there would be no such 'glacier walks' available, and this has come to pass.

Photo and text: Don Hitchcock 2013

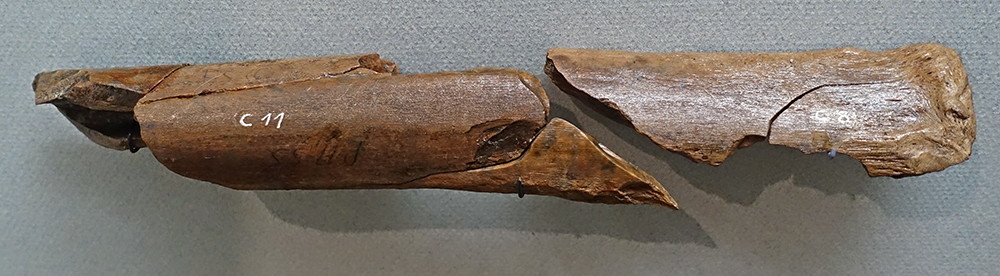

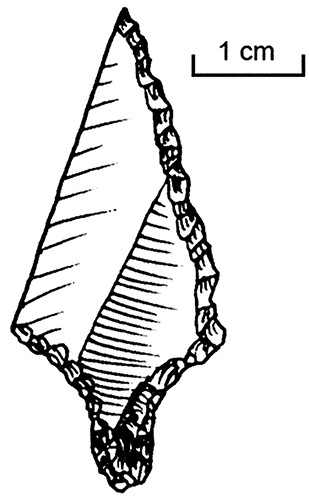

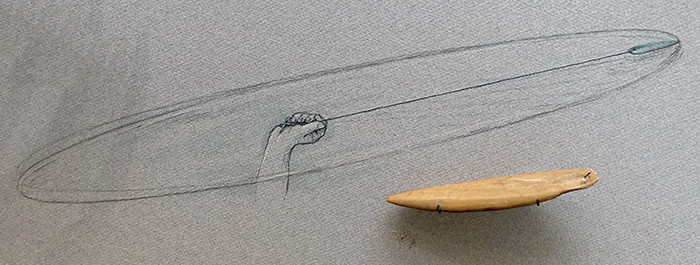

At the Stellmoor site, of the Ahrensburg culture, many pine arrow shafts were observed. They consisted of an approximately 80 cm long main shaft and a 15 cm long removable foreshaft.

These finds are the first sure evidence in Europe for bow and arrow hunting.

Among the wastes of the hunting stations at both Meiendorf and Stellmoor were found many skeletal remains of killed reindeer. In some bones, the fragments of flint arrowheads were discovered.

Stellmoor was a seasonal settlement inhabited primarily during October, and bones from 650 reindeer have been found there. The hunting tool was bow and arrow. From Stellmoor there are also well-preserved arrow shafts of pine intended for the culture's characteristic skaftunge (shaft tongue) arrowheads of flint. A number of intact reindeer skeletons, with arrowheads in the chest, has been found, and they were probably sacrifices to higher powers. At the settlements, archaeologists have found circles of stone, which probably were the foundations of hide teepees.

Photo: Rust (1943)

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Wikipedia

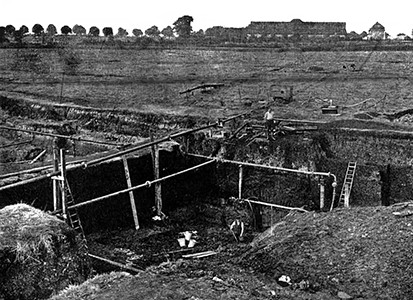

The site of Stellmoor during the excavation.

Top right the excavator Alfred Rust, taking a photograph of progress with a large glass plate camera steadied by a tripod. These glass negative cameras were used up until quite recent times because of their lack of distortion of the negative and resulting print.

( note the difficult, muddy conditions that the researchers had to contend with. The assistant's gumboots are deep in the mire - Don )

Photo: Rust (1943)

Rephotography and additional text: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

The site of Stellmoor during the excavation.

Stellmoor is an archaeological site of the late Palaeolithic near the Meiendorf area not far from Hamburg. The archaeologist Alfred Rust carried out excavations there in a silted late ice age lake in the years 1934 to 1936. There were two cultural layers.

At a depth of 650 cm, artefacts of the Upper Palaeolithic Hamburg culture were discovered: stone implements , animal bones (especially from reindeer ) and reindeer antlers, as well as two reindeer weighted with stones.

At a depth of 400 cm, there was a rich find with artefacts from the late Palaeolithic Ahrensburg culture. In addition to stone, bone and antler artefacts and wooden arrows, the remains of 650 reindeer were found. Twelve reindeer had been sacrificed. In addition, there was a cult object, which consisted of a two metres long pine wood pole, on which was mounted a reindeer skull with large antlers. This has been interpreted as a cult object.

Photo: Rust (1943)

Proximal source: http://mennesketsoprindelse.dk/beroemte-lokaliteter/europa/tyskland/ahrensburg-tunneldal-tyskland-stellmoor-og-meiendorf/

Text: Wikipedia

Ancient Scandinavia: An Archaeological History from the First Humans to the Vikings Front Cover T. Douglas Price Oxford University Press, 12 Jun 2015 - History - 416 pages

The site of Stellmoor during the excavation.

( It was a huge and expensive feat of engineering. Apart from the thousands of cubic metres excavated, the whole dig had to be kept clear of water as much as possible, as shown here by the pipes and pumping system - Don )

Photo: Rust (1943)

Proximal source: http://mennesketsoprindelse.dk/beroemte-lokaliteter/europa/tyskland/ahrensburg-tunneldal-tyskland-stellmoor-og-meiendorf/

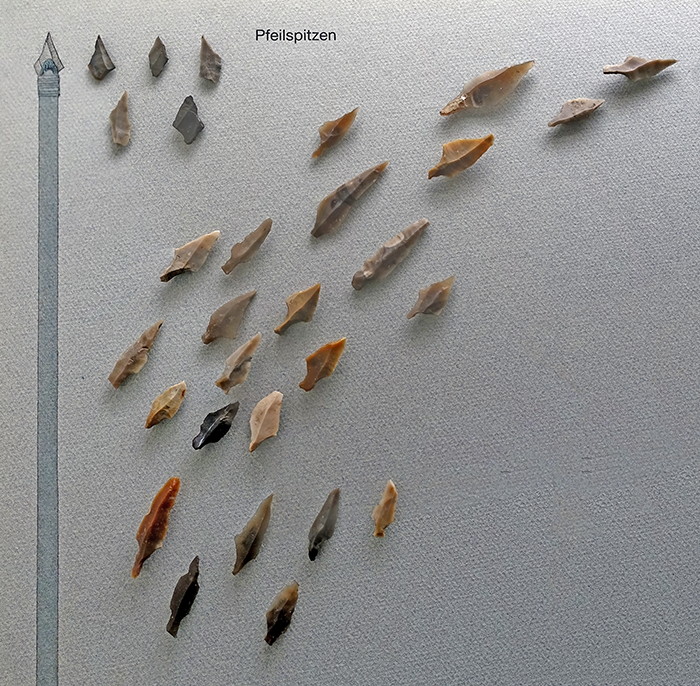

Ahrensburg culture

Key types of the stone tools of the last reindeer hunters

The typical tools are short, squat scrapers. Awls, typical of the Hamburg culture, are missing entirely, but there were flint arrowheads.

The antlers, wood and bones used for other tools were cut with burins and large, sharp blades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Using a large, sharp blade to cut an antler or bone into a useable size. It is likely that the maker of the tool simply scored right around the outside of the antler, and snapped it at the score mark, since that is the fastest and easiest way to do it.

Photo and text: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Sharp knife on a large blade.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Sharp knife on a large blade.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Sharp knife on a large blade.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Tools of unknown function.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

End scrapers on blades, grattoirs.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Short scrapers.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Arrow heads.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

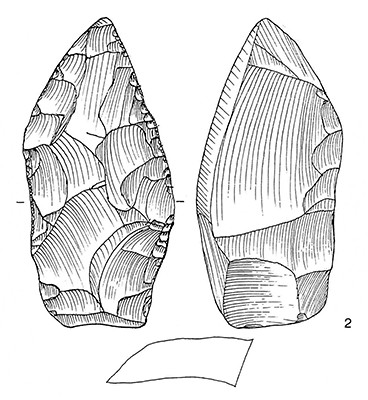

Ahrensburg culture

Skaftunge (shaft tongue) Ahrensburg culture arrowhead.

Arrowheads of this type may be seen in the image above.

Photo: http://www.wikiwand.com/en/Ahrensburg_culture

Ahrensburg culture

Arrow heads.

( The arrowheads were thin and small enough to be able to mounted on an arrow shaft, in a slot carved for them, secured with black birch bark glue and sinew - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Arrow heads.

( As always in this exhibition, the artefacts were superbly mounted, artistically displayed, and supported by very well executed and aesthetically pleasing watercolour illustrations. It was a joy to visit this museum - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Way of Life

An important characteristic of reindeer hunter communities is their high mobility.

During the warmer months, they moved from the larger autumn and winter camps in small groups to the summer hunting grounds. Here, besides reindeer, other game including fish and birds were hunted.

Perhaps the many scattered sites outside the Ahrensburg Tunnel Valley were such short-lived hunting stations.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

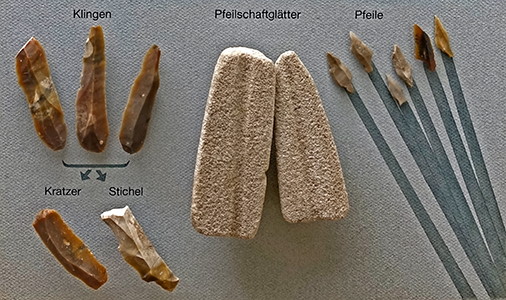

Ahrensburg culture

Equipment of a reindeer hunter

Flint debitage and the flint tools of a find site often do not match. Apparently not all the necessary equipment of the reindeer hunters was made locally, but a small basic assortment was brought along with them ( including the arrow shaft smoother shown here, essential for replacing broken arrow shafts - Don ).

( note here the illustration that shows the basic first step of the creation of a blade from a core being used for many purposes, including end scrapers (grattoirs) and burins. No doubt the debitage from burins in particular, because of the way they are made, was used to create the much smaller arrow heads with the minimum of extra effort - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

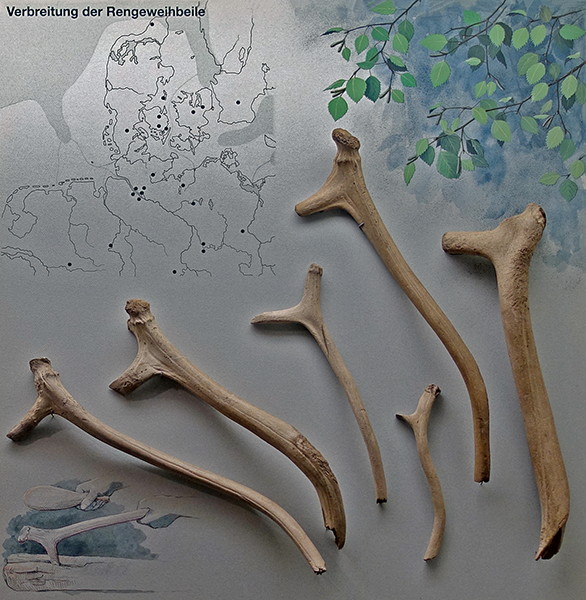

Ahrensburg culture

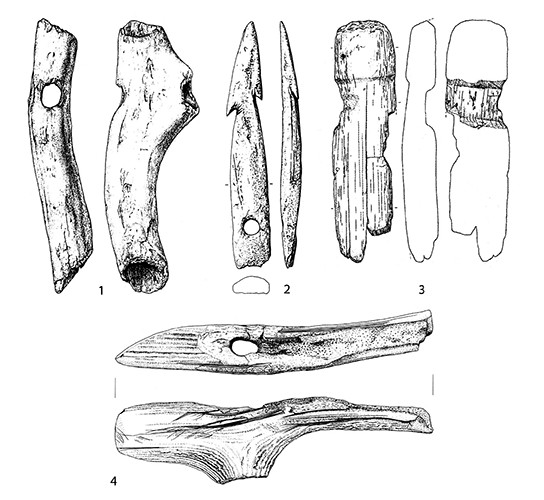

Bone and antler tools of the Ahrensburg culture

The favourable conservation conditions at Stellmoor have preserved over 20 000 bones and antlers. Among them is a large number of hatchets from reindeer antlers, which are suitable both as hunting weapons and for woodworking.

The map shows the distribution of reindeer antlers used in this way.

( These antler tools were used primarily for splitting logs into far more valuable planks, and by continued splitting, into blanks for spear or arrow shafts. Their existence shows that at this time the reindeer hunters were still able to find trees worth cutting down and using in this way, despite the general quite cold conditions which resulted in vegetation of all kinds being stunted - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Harpoons.

( note the unusual end to the nearly complete harpoon head on the left. It is spade shaped. Harpoons were used not only for fish but for other game as well. The detachable forepiece meant that if it were broken, an easily carried spare harpoon head could be lashed onto the valuable and hard to replace spear shaft while in the field, and hunting could continue. Both harpoon heads are flattened in cross section - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Harpoons.

( note that this harpoon head also carries the remains of a spade shaped end similar to the one in the image above - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Harpoons.

( note that the harpoon head on the right is flattened in cross section, and has an arrow shaped end for attachment to the spear shaft, and is much shorter than most harpoon heads. It may have been reshaped into this short form after a longer version had the tip broken off - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

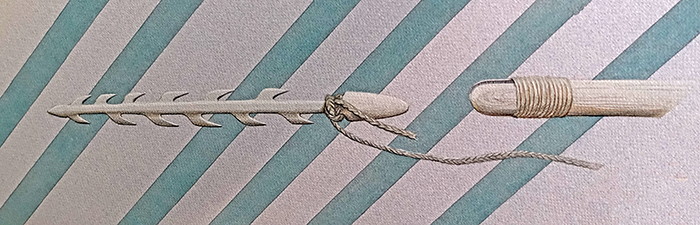

Ahrensburg culture

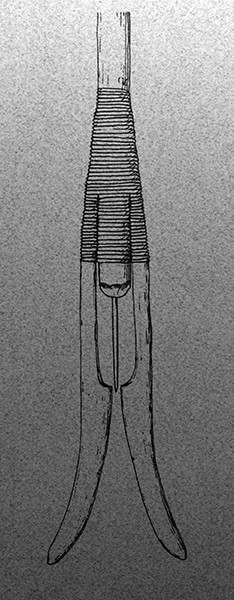

Harpoon head, method of attachment.

( this drawing shows the harpoon head as being attached by a plaited leather thong, with the harpoon head designed to come off the shaft on impact - Don )

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Ahrensburg culture

Bullroarer.

When attached to a string, and whirled around in the air, this bone produces a loud, piercing sound.

( these musical instruments are part of many cultures, ancient and modern - Don )

rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

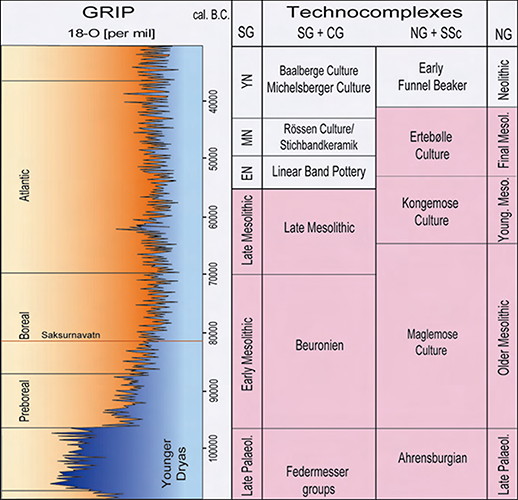

The Mesolithic in Schleswig-Holstein

Chronostratigraphy of the Mesolithic.

SG – southern Germany;

CG – central Germany;

NG – Northern Germany;

SSc – southern Scandinavia.

Photo and text: Terberger and Hartz (2003)

Maglemose Culture

11 000 BP to 8 000 BP

Maglemose Culture

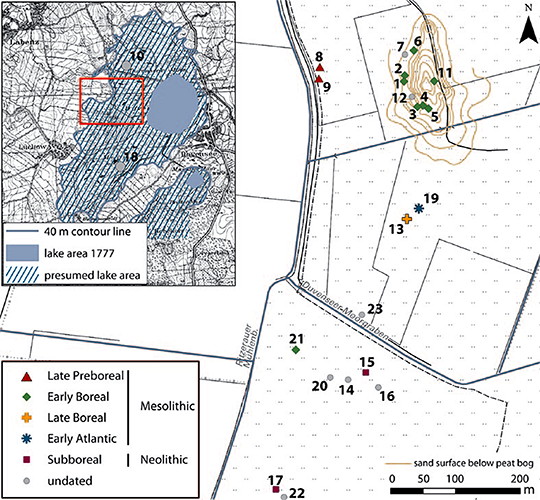

Southern Scandinavian and Northern German Maglemose sites.

Preboreal sites: 1. Lundby kettle hole lake deposits (Hansen et al. 2004; Jessen et al. 2015); 2. Skottemarke elk deposits (Møhl 1980; Sørensen 1980; Fischer 1996); 3. Favrbo elk deposits (Møhl 1980); 4. Vig aurochs deposit (Hartz and Winge 1906); 5. Nørregaard VI (Sørensen and Sternke 2004); 6. Årup contexts 1, 2 and 3 (Karsten and Nilsson 2006); 7. Barmosen I (Johansson 1990); 8. Bjergby Enge (Andersen 1980); 9. Klosterlund (Mathiassen 1937; Petersen 1966); 10. Gl. Ullerød (Jensen 2002); 11. Draved 611, 604s and 332 (Sobotta 1991); 12. Henninge boställe (Althin 1954); 13. Hasbjerg II (Johansson 1990); 14. Flaadet (Skaarup 1979); 15. Mullerup; 16. Sværdborg; 17. Holmegaard; 18. Åmosen; 19. Pinnberg 7 (Rust 1958a); 20. Duvensee; 21. Hohen Viecheln (Schuldt 1961); 22. Rothenklempenow 17 (Schacht and Bogen 2001); 23. Potsdam-Schlaatz (Benecke et al. 2002); 24. Friesack (Gramsch 2002); 25. Bedburg Königshoven (Street 1989); 26. Mönchengladbach-Geneicken (Heinen 2014).

The map illustrates the land masses at the Pleistocene/Holocene transition (compiled by Grimm 2009 after Björck 1995a; Boulton et al. 2001; Lundqvist and Wohlfahrt 2001; Weaver et al. 2003; Clarke et al. 2004; Brooks 2006b; Ivy-Ochs et al. 2006; with further additions from Woldstedt 1956; Björck 1995b; Björck 1996; Zahn 1996; Coope et al. 1998, figure 4H; Kobusiewicz 1999, 190; Gaffney et al. 2007, 3–7 and 71) (Copyright Daniel Groß, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Photo and text: Sørensen, Lübke, and Groß (2018)

Before the Maglemose culture was defined, Stone Age archaeology was already well established in Southern Scandinavia, arising from the discovery of coastal shell middens which were investigated by the ‘Kitchen midden commissions’ and dated to the Ertebølle culture (Late Mesolithic). However, in 1900 a new type of site was discovered by the National Museum trained botanist and archaeologist Georg Frederik Ludvig Sarauw (1862–1928). On the 8th of June 1900 he was sent by the National Museum to the bog of Mullerup in Western Zealand.Text above: Sørensen, Lübke, and Groß (2018)

Here a local teacher (M. J. Mathiassen) had reported unusual, well-preserved finds of ancient bones, charcoal and lithics from the bog during peat cutting. Sarauw immediately undertook an excavation to an unusually high quality standard for the time, examining the geological layers and botany within the bog as well as the spatial distribution of the artefacts and their stratigraphic position. In 1903 he published a thorough account of this excavation and coined the term 'Maglemose'. He argued that what he had found was not an Ertebølle cultural site but something older: an inland culture that lived within large bogs and had an economy based on aquatic and terrestrial resources (Sarauw 1903).

The culture was first called 'Mullerup', after the nearby village; however, as the local bog was called 'Maglemose' the culture was finally named after the bog. In fact, 'Maglemose' means 'large bog' in Danish and there are many Maglemose place names all over Southern Scandinavia. Thus, in the Danish language the Maglemose culture simply means the Stone Age culture found in large bogs. In 1904 a new site was found in the Maglemose bog of Mullerup just north of the first one. This was investigated in the same year and then again in 1915.

( I feel I should note here that the entire report of Sørensen, Lübke, and Groß (2018) is superbly written, and is a credit to the authors. It is a pleasure to read such beautiful, well crafted English, and the professionalism, presentation and organisation of this paper are exceptional - Don )

Maglemose Culture

Elk antler axes, wedges and chisels. Found during peat-digging at various bogs.

Early Maglemose Culture, 10 700 - 9 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Maglemose Culture

Elk antler wedges from the same display above. Found during peat-digging at various bogs.

Early Maglemose Culture, 10 700 - 9 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Maglemose Culture

The tool on the left, apparently a facsimile, appears to be either an adze, or a handled wedge for splitting timber, made from moose /elk antler. Note that the maker has carefully put the hole for the handle at a thickening in the antler, to provide more strength at the junction, where much stress would be applied.

The tool on the right is an adze, and may be original.

Early Maglemose Culture, 10 700 - 9 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Maglemose Culture

A wounded elk (moose) sank exhausted to the bottom of a lake at Tåderup on Falster 8 700 years ago. In 1922 the skeleton was found in a peat bog. Among the bones was a broken bone point that may have been used in the hunt. Later a harpoon was found in the same peat bog.

Several kinds of tools and weapons were made from the large animals' antlers and slender bones. The hunting was so intensive that the species was wiped out in Zealand ca 8500 years ago. However the elk still played an important role in the hunters' mythology. Tooth beads, and tools of elk antler and bone were valuable barter objects.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark.

Maglemose Culture

Bone harpoon, found near the elk skeleton. Tåderup, Falster, ca 8 700 BP.

Bone point, broken, found among the elk's remains. Tåderup, Falster, ca 8 700 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Apparently facsimiles, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark, on loan from Lolland-Falsters Stiftsmuseum.

Maglemose Culture

Harpoons made of elk or red deer bone/antler. Found during peat-digging in various bogs. Maglemose Culture, 10 700 - 8 500 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Apparently originals, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark.

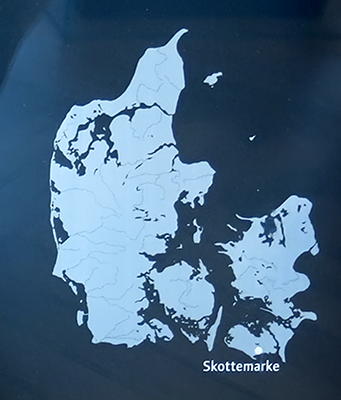

Maglemose Culture

Fish spears of bone from an elk-hunting site at Skottemarke, Lolland.

Early Maglemose Culture, 10 700 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Originals, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark.

Map showing the position of Skottemarke.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Display, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark.

Maglemose Culture

Flint axes from an elk-hunting site at Skottemarke, Lolland.

Early Maglemose Culture, 10 700 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Originals, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark.

Maglemose Culture

Flint axes from an elk-hunting site at Skottemarke, Lolland.

Early Maglemose Culture, 10 700 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Originals, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark.

Maglemose Culture

Flint axes from an elk-hunting site at Skottemarke, Lolland.

Early Maglemose Culture, 10 700 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source and text: Originals, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark.

Maglemose Culture

Serrated bone points, thought to be used on fish in particular.

( these increase bleeding or shock in the prey, which immobilises them more quickly - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

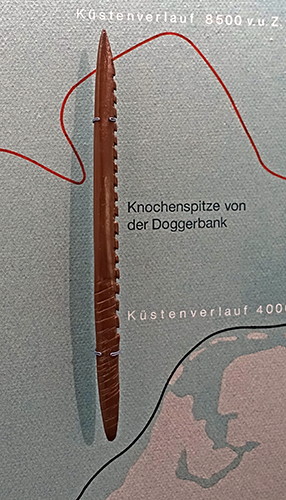

Serrated bone point dredged from the Dogger Bank, of the same type as those above.

( note that this may be a museum quality facsimile - Don )

Photograph: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

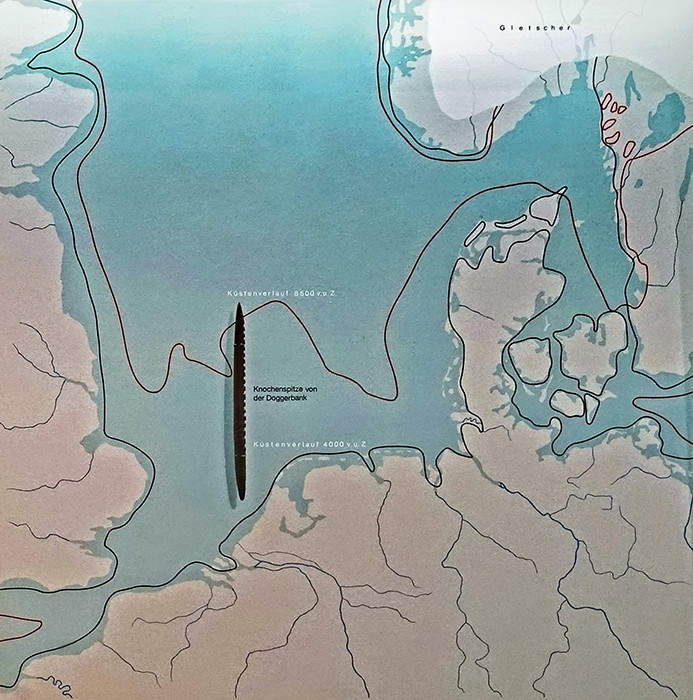

Land and sea

In the early and late Ice age Northwestern Europe formed one coherent landmass. Sea level was more than 50 metres lower than today. As the climate warmed, the ice melted and flooded what is now the North and the Baltic Sea. Schleswig-Holstein gradually assumed its present form.

Settlement patterns

The people of the Mesolithic hunted, fished, and collected according to the season. Preferred settlements were the banks of rivers and lakes, as well as islands in the middle of larger bodies of water.

When the Maglemosian culture flourished, sea levels were much lower than now and what is now mainland Europe and Scandinavia were linked with Britain. The cultural period overlaps the end of the last ice age, when the ice retreated and the glaciers melted. It was a long process and sea levels in Northern Europe did not reach current levels until almost 8000 BP, by which time they had inundated large territories previously inhabited by Maglemosian people. Therefore, there is hope that the emerging discipline of underwater archaeology may reveal interesting finds related to the Maglemosian culture in the future.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Wikipedia

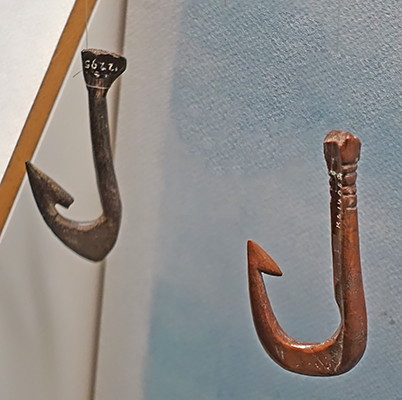

Maglemose Culture

Bone fishing hooks, from Schinkel, Kr. Rendsburg-Eckernförde, and Kleinsolt, Kr. Schleswig-Flensburg.

( We can see here two different methods of attaching a line to the hook. In one case the hook has been made with a larger end than the main part of the hook. In the other case, the end has been grooved to provide a secure attachment point. A hole in the shank of the hook is preferable, but probably this weakens the hook too much when made in bone of this diameter - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Maglemose Culture

Fish hook.

Ferchesar, Germany.

10 000 BP - 7 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile (?), Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

On loan from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte.

Maglemose Culture

Fish Hooks

(left and centre) Ferchesar, Brandenburg, 11 000 BP - 8 000 BP

(right) Fernewerder, Brandenburg, 11 500 BP - 7 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Maglemose Culture

Fish Hooks

(left) Seedorf, Schleswig-Holstein, 11 500 BP - 7 500 BP

(right) Billeberga, Schweden, 11 500 BP - 7 500 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Maglemose Culture

Net weaver, decorated.

Wismar, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 11 500 BP - 7 000 BP (original)

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Maglemose Culture

(above) Net weaver, decorated.

Fernewerder, Brandenburg, 11 500 BP - 7 000 BP

(below) Blunt needle used for threading, made of antler.

Duns Kjökk, Schleswig-Holstein, 7 000 BP - 11 500 BP (original)

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

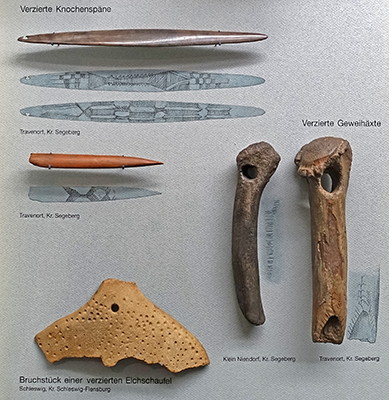

Maglemose Culture

Decorated pieces of bone and antler, and a piece of a decorated scoop.

( the polished and decorated bone object at the top left of this image from Travenort, Kr. Segeberg was a tool for making fishing nets. The offset incomplete hole allows for the easy insertion and removal of cord as necessary - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Maglemose Culture

Fishing net, 10 000 BP - 7 000 BP.

Reconstruction from a find in Friesack, Germany.

Materials: bast (inner bark fibre), outer bark, pebbles.

( note that the technician has used bark as floats for the net. Other woods might have been more suitable, or perhaps blown up deer or reindeer bladders - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

Maglemose Culture

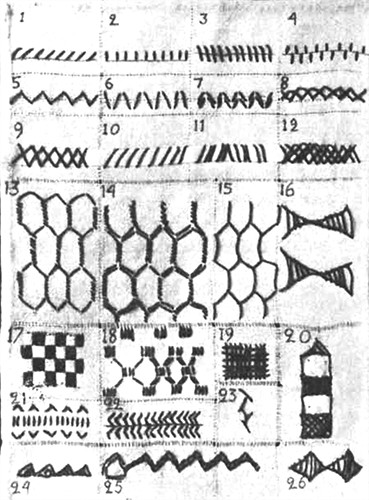

Typical designs for engravings on bone and antler by the Maglemose Culture.

These have been described by Hultén (1939) as being based on the patterns formed when stitching and repairing leather garments.

Photo: Hultén (1939)

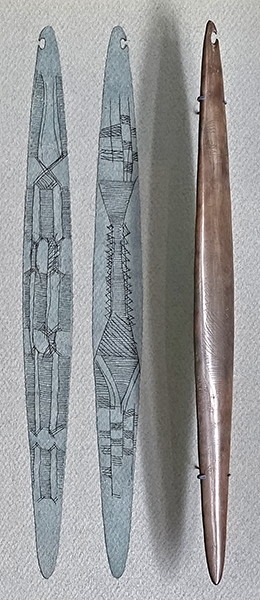

Maglemose Culture

( Here, Hultén (1939) posits that the engraved designs on Maglemose bones and antlers were representations of the already existing patterns on clothing, where seams and stitching were used to join and strengthen leather garments.

Hultén (1939) further suggests that these workaday inherent patterns were copied onto bone and antler tools in order to give magical strength to the objects - Don )

Modern embroidery abounds with more or less stylised naturalistic motifs, which were quite unknown to the Maglemose people. This allowed only the seam to be a suitable reinforcement of the hide. This reinforcement effect is further increased by the fact that the front and back side patterns must not be congruent, but alternating, which often characterises these motifs. (Compare below, however, about some different designs of the chess pattern!) Reinforcement of the hide was so much more necessary, as this in itself must have been very fragile because of the imperfect preparation methods. Probably they tried to get it soft only by scraping and chewing. Possibly, however, the Inuit urine method was also used, in which case the lack of earthenware was remedied by the use of hollowed-out tree trunks.

The findings of oars both in Duvensee and Holmegaard show that they had boats, and adzes, which were suitable for carving out tree trunks, especially if the wood was first burned.

The Maglemose patterns are easy to sew without any previous marking other than holes or marked points. They remind one of contemporary embroideries, which are sewn over counted threads and are generally considered more valuable than those sewn in a drawn pattern.

In the following respects, on the other hand, the Maglemose patterns deviate from the currently used embroidery patterns: They almost never consist of finished motifs, but are detached pieces of borders or surface patterns, which could be continued indefinitely.

Very often, the carvings not only depict the stitches, but also the edge of the leather lying beneath them. Sometimes the seam is surrounded by two parallel lines, which are likely to either represent an applied strip of leather or the fine creases that arise if the stitches in thin skins are drawn together tightly. As long as the small oblique or transverse lines were engraved in immediate connection to a place that needed to be reinforced, the intention was fully clear and the magic effect thus ensured. But when the decoration was intended to increase the object's strength and durability in general, these short continuous strokes were not always considered sufficiently clear. It was then preferred that either the engraving should also depict an underlying tear or splice or choose a type of stitch with a more pronounced character.

This method of decorating a completely undamaged object with both cracks and seams to thereby magically increase its durability appears to be rather quirky and far-fetched. However, the culture's perception repairs must have been quite different from ours, because at that time they did not know of any other material to sew on than skins, and on leather a repaired tear is always stronger than the material itself. Even today, the cutter first cuts the skin and then sews it together again, so that it will not tear.

On the reverse of the leather in a fine coat, one can see that it consists of countless small strips, sewn together with parallel seams, which are placed in different directions on the different parts of the garment. For the Maglemose people, seams and reinforcement must be synonymous concepts, and it therefore naturally occurred to them that a copy of both tears and repairs should have a strong magical effect, and most faithfully depicted the tear at the most fragile place. When designing the motif in question, called by Clark the barbed line, it was not always necessary to lay the stitches on both sides of the joint. One could also imagine one piece of leather laid on top of another and the stitches walking around the edge itself

Barbed lines of different kinds occur on more than one third of all carved items from the Maglemose time. However, the zigzag line is even more common. It can be done in two ways: with a short stitch on the wrong side of each angle or using only long stitches. Both variants constitute good reinforcement seams, whether they are made stand-alone or if they are laid over a join. However, the one with only long stitches entails an impractical waste of thread, because it must be sewn twice and then exactly the same on both sides. It is therefore more likely that the piece of bone here, as in so many other primitive drawings, depicts what he knows is there, namely the part of the thread running in the opposite direction. On a horn tip from Svärdborg are two lines of zigzag lines, in which one line is always simple, while the other is double to quadruple. Here, the design has either with a simple line tried to indicate the thread on the back, or also imagined a seam performed twice, one with single and the other with multiple thread. Exactly the same line is also found on a richly decorated 'netstick' from Travenort in Holstein, but here one side lines are almost consistently double. On the same piece, there is a beautiful chess pattern.

Photo (left) and text: Hultén (1939)

Photo (right): Don Hitchcock 2018, from the source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Maglemose Culture

Art designs from the Maglemose Culture.

1. Langeland Island.

2. Sværdborg, Zealand.

3. Bohuslän, Sweden.

4. Klein-Machnow, north Germany.

5. Sværdborg, Zealand.

6. Mullerup, Zealand.

7. Resen Mose, Jutland.

8. Taarbæk, Zealand.

Photo and text: Clark (2014)

Maglemose Culture

Decorated antlers with the barbed line motif in combination with a horizontal zigzag-line.

1. Szczecin-Podjuchy, Poland.

2. Grotte du Placard, France.

3. Holmegård IV, Denmark.

4. Friesack 4, Brandenburg.

Photo and text: Terberger and Hartz (2003)

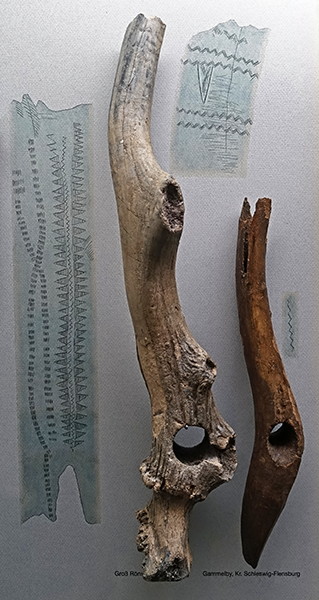

Maglemose Culture

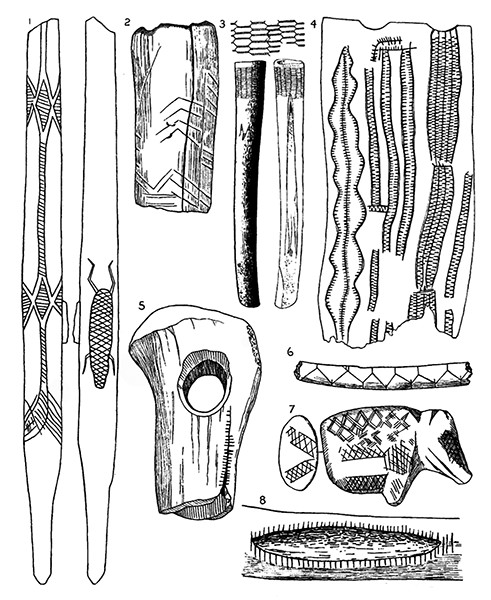

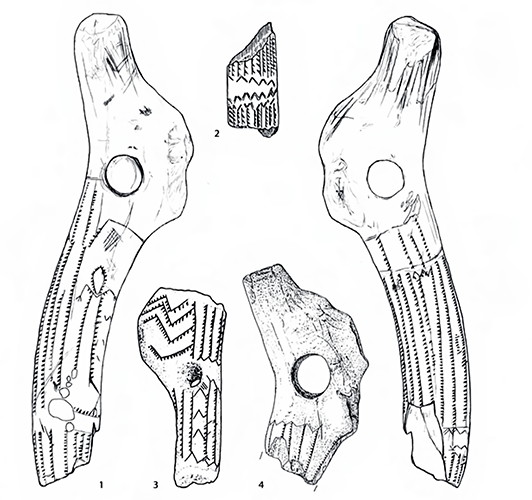

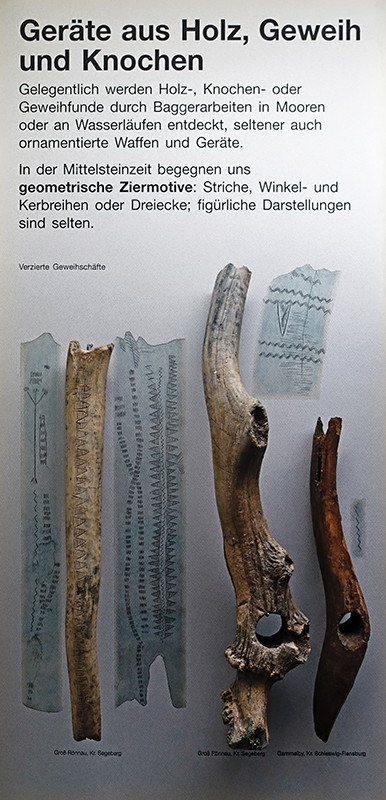

Wooden, antler and bone tools.

Occasionally, pieces of wood, bone or antler are discovered by dredging in bogs or watercourses. More rarely, ornamented weapons and equipment are found.

In the Mesolithic, the Middle Stone Age (10 000 BP - 5 000 BP), between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods, at the end of the last ice age, we encounter geometric decorative motifs: lines, angles and notched rows or triangles. Figurative representations are rare.

During the Mesolithic, the emphasis was on small or even tiny tools, microliths, rather than the larger tools used previously. There was also greater use of wooden handles for tools, including the adze. Domestication of animals had begun, including the dog.

Decorated reindeer bones. Described in Rust (1943), but not from Stellmoor. They are from the Maglemose Culture.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Wikipedia

Maglemose Culture

Closeups of the decorated bones and their engravings.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Maglemose Culture

Birchbark box

Reconstruction of a box found at Friesack, Germany.

10 000 BP - 7 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

Maglemose Culture

Bow of elm from Holmegaard, southern Zealand, circa 9 000 BP.

The original Holmegaard bow, from the Maglemose culture.

The bow and arrow were the technological innovations that made hunting very efficient. In the forest throwing spears was difficult, but with weapons like the bow from Holmegaard the game could be shot even in thick vegetation - in fact, with care, this allowed the hunters to get very close to their prey, making the shot much easier to make accurately.

Photo (above) of the original bow: Don Hitchcock 2014

Photo (below) of a facsimile: rephotographed from a poster at the Københavns Museum

Source and text: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Maglemose Culture

This is a replica of the oldest preserved bow , from the Holmegaard Moor in Denmark.

It is made by Greg Anderson, an avid lover of the outdoors and also a primitive skills and wilderness survival expert. It is from these passions that he came to study the ancient art of bow making. He founded North Wood Traditional Archery LLC in 2010.

The original Holmegaard bow is 1540 mm long, made from the trunk of an elm tree, that had been split down the middle. The weapon has a 26 mm wide grip, which possibly didn't bend. Its limbs have a maximum width of 45 mm.

Photo and text: http://www.northwoodtraditionalarchery.com/archery_hunting_bow_hunting.html

Maglemose Culture

Holmegaard Bow

Another reproduction of the bow, as well as an arrow that may have been of the type used, on display in the Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, Germany.

Circa 9 000 BP.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann, near Düsseldorf, Germany

Maglemose Culture

This is an excellent photo of the Holmegaard bow in action, with the archer in period costume. Note the environment - the bow and arrow have many advantages over spearthrowers and darts, even on the steppes, but it is in a forested setting that they become clearly superior.

This particular reconstruction is 62 inches long. It pulls 55 pounds at 27 inches of draw (1575 mm, 25 kg, 686 mm). The bowstring is twisted deer rawhide. The nocks are built up with twisted cordage, pine pitch, and sinew, the original artefacts having no carved nocks. The handle is wrapped in twisted elm bark cordage.

For the original, the belly of the bow has a flattened shape. On the back of the object there are some marks that are interpreted as the evidence of strengthening the bowstring made of sinews, by fixing it firmly to the edge of the bow. The limbs of the bow taper gradually toward the end. This hunting tool was carved out from the tree so that its back was the flexible sapwood while the belly was the harder heartwood. This wasn’t the only bow that was discovered in Holmegaard Moor, four other very similar objects were also found, all of them are made from elm.

One of the other bows was larger, originally around 1620 mm long. The grip is 21 mm wide, the maximum width of the limbs of this bow is 60 mm. These bows are considered as wide-limbed bows. This broad-limb feature is for reinforcing, useful to reduce strain from the bow, keeps the string more durable and altogether increases the efficiency of the weapon. The narrow grip makes the bow easier to handle while being used. The trees that the bows were made of were chosen from those that grew in the shade, so that they did not have any branches or knots. These hunting weapons are dated to around 9 000 BP.

Photo and text: Airborne890, http://www.primitivearcher.com/smf/index.php?topic=57844.0

Additional text: Bálint (2014)

Maglemose Culture

Forearm protection plate for an archer, as protection against chafing from the bowstring.

Wismar, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 11 000 BP - 8 000 BP

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Lake Duvensee

Maglemose Culture

11 000 BP to 8 000 BP

Birken-Kiefern-Zeit - The Birch-Pine Period, Early Maglemosian culture

The ancient lake bed at Duvensee was formed during the Older Dryas as a dead-ice kettle hole left by the retreating Fennoscandian ice sheet. The water level rose during the Allerød and the lake reached its largest extent during the early Preboreal. The water level fluctuated during the late Preboreal and Boreal, but over the course of the Holocene the lake gradually silted up and was overgrown by peat.Text above: Groß et al. (2018)

Sites of the Birken-Kiefern-Zeit - The Birch-Pine Period.

( The site of Duvensee is marked here - Don )

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

The Duvensee bog, or Lake Duvensee, is located at the edge of the Duvensee municipality in the Herzogtum (Duchy of) Lauenburg district in the southern part of Schleswig-Holstein. The bog formed from a paludifying (peat-forming) lake that originated as a kettle hole (ice left behind as the ice sheet retreated, surrounded and often covered with sediment, thus forming a lake when the ice eventually melted) during the early pre-boreal, and which once covered an area of more than 4 square kilometres. Siltation set in during the late pre-boreal and the lake was (intentionally) drained in its entirety during the 19th century.Text above: Wikipedia

The north-western banks of the lake served as areas for human activity during the early Mesolithic. On two peninsulas the remains of small to medium-sized sites in close vicinity to one another were found.

With increasing formation of peat, which is thought to have set in during the periods of occupation, the sites were covered and protected by the thick layers of peat and survive in excellent condition. Due to increased peat harvesting during the 19th and 20th centuries, the as yet unexcavated portions are now close to the surface and are no longer protected by this natural cover.

Lake Duvensee

Dating and location of sites in the central western area of the ancient lake Duvensee.

Small map: the maximum extent of the lake in the early Holocene (base maps: © GeoBasis-DE/LVermGeo SH).

Photo and text: Groß et al. (2018)

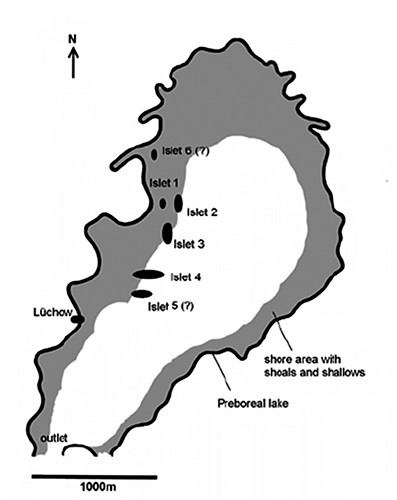

Lake Duvensee

The Preboreal Duvensee lake with islets, shallows and the Lüchow site.

(map K. Bokelmann).

Photo and text: Bokelmann (2012)

Lake Duvensee

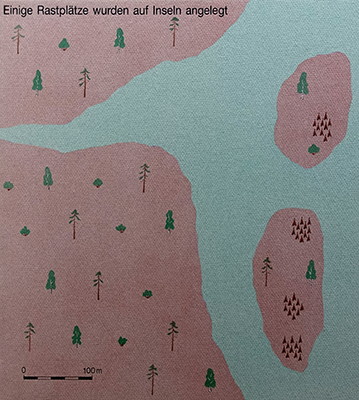

Development of the Duvensee bog, Schleswig-Holstein, from the Preboreal to the Atlantic.

Source: after Bokelmann (1991).

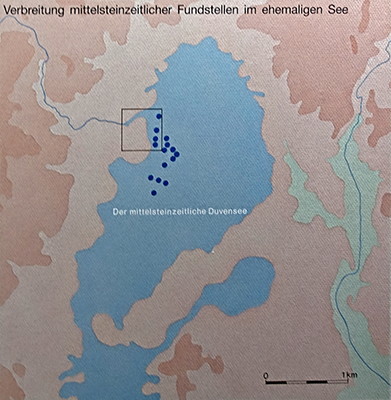

Lake Duvensee

(left) Distribution of Mesolithic sites in the former lake.

(right) Some camps were made on islands.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee

View of the western 'shore' of the Duvenseer Moor. The left tent is partially on the edge of the former lake, the corn field in the middle ground has been sown on the preboreal Gyttja. To the right of the survey rod is Duvensee, Wohnplatz 8.

( Gyttja is a mud formed from the partial decay of peat. It is black and has a gel-like consistency - Don )

Photo and text: Bokelmann (1991)

Additional text wikipedia

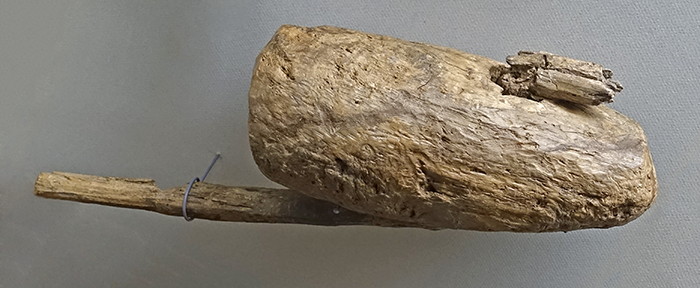

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 1 (Wohnplatz 1, W1, Wp1)

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 1, Wp1

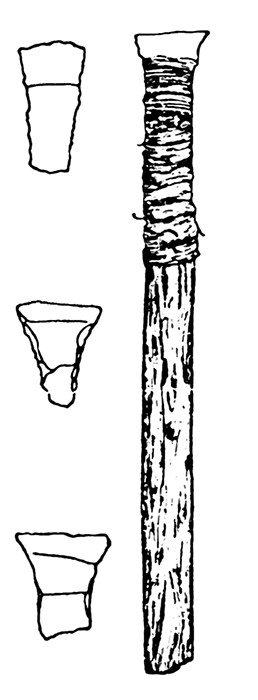

An extraordinary find from Lake Duvensee was this wooden axe made from root wood with the wooden handle still preserved.

Photograph: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Text: Groß et al. (2018)

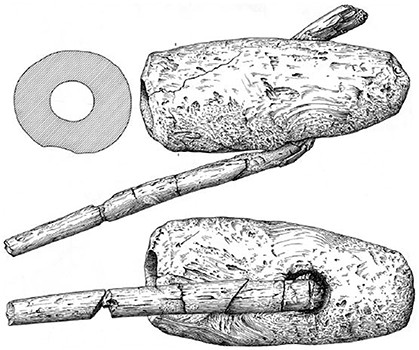

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 1, Wp1

Drawing of the axe from Duvensee WP 1 (© Archaeological State

Museum Schleswig-Holstein).

Photograph and text: Groß et al. (2018)

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 1, Wp1

Wooden axe from Lake Duvensee.

Photograph: © Museum für Archaeology Schloss Gottorf

Source: https://www.facebook.com/SchlossGottorf/photos/a.280572935406644/952887261508538/?type=3&theater

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 2 (Wohnplatz 2, W2, Wp2)

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 2, Wp2

The Duvensee Paddle.

One of the world's oldest surviving wooden paddles.

Date circa 8 200 BP (Mesolithic).

Medium: pine wood.

Dimensions: Length: 520 mm. Width: 182 mm. Depth: 35 mm. Weight : 331 g (11.67 oz).

Catalog: MfV1926.112:182

Photo: This image was provided as part of the cooperation with Archäologisches Museum Hamburg (Archaeological Museum Hamburg)

Permission: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany license.

Attribution: Archäologisches Museum Hamburg

Source: Wikipedia

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 2, Wp2

The back of the Duvensee Paddle.

Dimensions as given in Hartz and Lübke (2000):

(-Wpl. 2) LA 18, Kr. Hzgt Lauenburg: pine, fragment.

Blade: length 340 mm, width 140 mm, thickness 20 mm.

Shaft: length 330 mm, diameter 33 x 28 mm.

( note that these dimensions differ from those given above from the entry in Wikipedia - Don )

Photograph: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

References cited by Hartz and Lübke (2000): Schwantes (1939), Clark (1975)

The Duvensee paddle made from pine wood was found in Wp2 and is among the oldest direct evidence for water transport.Text above from Wikipedia

Pine and birch bark mats of up to 5 square metres in size were discovered at several sites (Wp 8, Wp11, Wp13 and Wp19) in association with hearths and roasting fires. They may have served as insulation against the dampness emanating from the bog.

Two arrow shafts made from hazel and pine wood were discovered at Wp6.

An axe shaft made from pine wood preserves evidence for the preparation of shafts of Mesolithic axes (tranchet axe and core axe).

Bone points with fine serrations have been placed into their own regional type or industry ('Typ Duvensee')

However, the majority of finds are lithic tools and by-products of their production made from flint. These form the basis for technological and spatial analyses at the site. The paddle and all finds from Wp1 through Wp5 are curated at the Archaeological Museum Hamburg, whilst all other finds are stored at the Archäologisches Landesmuseum Schleswig.

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 2, Wp2

The Duvensee Paddle at the time of its discovery in the 1920s.

Photo: © Museum für Archaeology Schloss Gottorf

Source: http://www.zbsa.eu/juli-en/juli?set_language=en

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 2, Wp2

The paddle of Duvensee is the second oldest paddle worldwide after the paddle of Star Carr and is considered one of the earliest records of the use of water vehicles in the Middle Stone Age.

The former Duvenseer Moor is located directly west of the village Duvensee in a young moraine landscape and had an extension of 3.5 km north-south and 1.2 km in west-east direction. Originally, it was a shallow, open lake that gradually filled with peat and eventually silted up. During mapping work in 1923 , the geologist Karl Gripp accidentally discovered a Mesolithic settlement site in the Duvenseer Moor. In the following years, the site was extensively archaeologically examined. In the years 1924-1927 Gustav Schwantes , 1946 Hermann Schwabedissen and 1966-1967 Klaus Bokelmann made archaeological excavations in the moor, and numerous residential sites were documented. In addition to numerous stone artefacts, the excavations produced very few wooden tools, among them the paddle found in 1926 in the Schwantes excavation campaign, which lay in a former riparian zone in the area of Wohnplatz 2. The paddle of Duvensee is one of the most outstanding finds from the Duvenseer Moor.

Location: 53 ° 41 '57 " N , 10 ° 32' 50,6" E Coordinates: 53 ° 41 '57 " N , 10 ° 32' 50,6" EThe elementary school teacher Ernst Bornhöft, who teaches in nearby Schiphorst, found two more paddles before 1925, which he first incorporated into the prehistoric collection of his school. Both paddles, however, went to the museum in 1925. The one large-leaved paddle made of oak wood has the dimensions 790 × 182 × 35 mm with a weight of 613 g and is still in the inventory of the museum. It was established in 2008 by means of 14 C-dating to 1121 ± 22 BP in the transition period from the early to late Middle Ages. The second paddle is lost today, there are only a few written records and a photo of the find.

The Duvensee paddle was broken several times during its discovery but it is exceptionally well preserved apart from a few defects. The paddle is missing only the end of the handle and the blade has a corner broken stepwise. The present paddle now has a length of 520 mm, a width of 100 mm and a thickness of 35 mm. The long rectangular blade with wide rounded corners has a length of about 260 mm and merges asymmetrically into the shaft. The weight of the paddle is now 331 g. The paddle was made from the carved trunk of a pine tree. After recovery, the paddle was not accurately documented, and was preserved with a waxy substance.

Radiocarbon dating in the 1980s on several hazelnut shells and wood remnants at the place of discovery resulted in an average dating of 9 390 ± 80 BP. The 2008 radiocarbon dating of two samples from the Duvenseer paddle using accelerator mass spectrometry ( 14 C-AMS) yielded calibrated age of 8 477 ± 49 BP and 8 261 ± 38 BP.

Length: 520 mm (20.47 ″); Width: 182 mm (7.16 ″); Depth: 35 mm (1.37 ″)

Photograph: Bullenwächter

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Source: Archäologischen Museum Hamburg | Helms Museum Hamburg-Harburg, Germany

Text: adapted from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paddel_von_Duvensee

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8 (Wohnplatz 8, W8, Wp8)

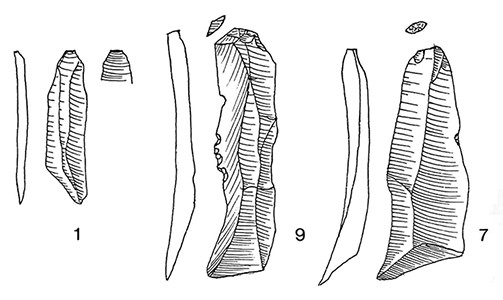

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Blades.

( Blades were the starting point for most flint tools apart from hatchets, including knives, scrapers, burins, awls and drills - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Arrowheads.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Burin-like tools.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Retouched blades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

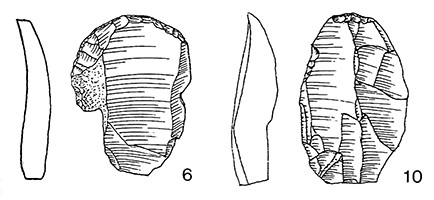

Hatchets.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

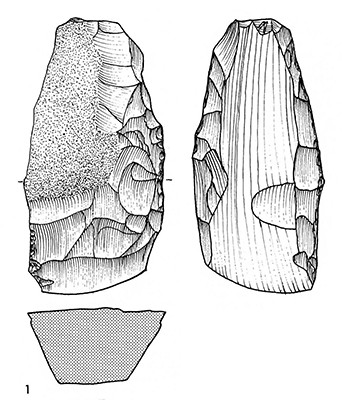

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Both sides and the cross section of the hatchet on the left in the image above.

Number 1, Taf. 2.

Photo and text: Bokelmann (1981)

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Hatchets resharpened after use.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Cores.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 8

Core.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9 (Wohnplatz 9, W9, Wp9)

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Arrowheads.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Waste pieces from the manufacture of arrowheads.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Jagged, dentate tools.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Cores.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Blades.

Photo (left): 1, 9, 7, Taf. 2. Bokelmann (1991)

Photo (right): Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Scrapers, 6, 10, Taf. 3.

Photo (left): Bokelmann (1991)

Photo (right): Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

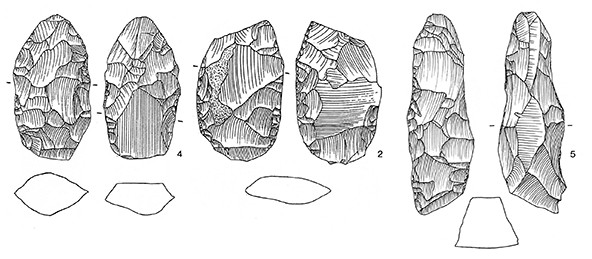

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Hatchets. (left, centre, no 4, no 2, Taf. 7, right, no 5, Taf. 8 )

Photo (above): Bokelmann (1991)

Photo (left): Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

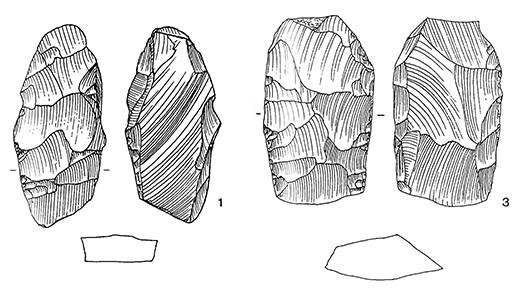

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Hatchets, 1, 3, Taf. 7.

Photo (left): Bokelmann (1991)

Photo (right): Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

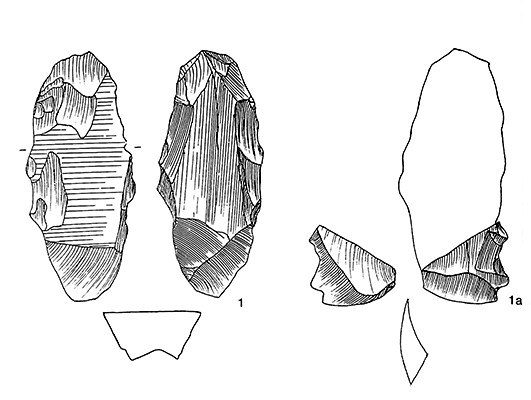

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Resharpened hatchet 1, 1a, Taf. 4.

Photo (left): Bokelmann (1991)

Photo (right): Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Lake Duvensee - Campsite 9

Resharpened hatchet 2, Taf. 6.

Photo (left): Bokelmann (1991)

Photo (right): Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

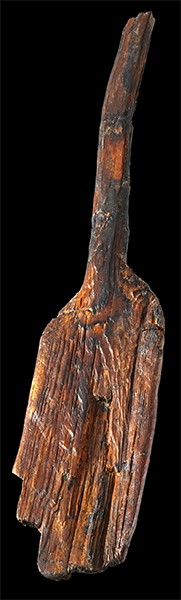

Duxmoor

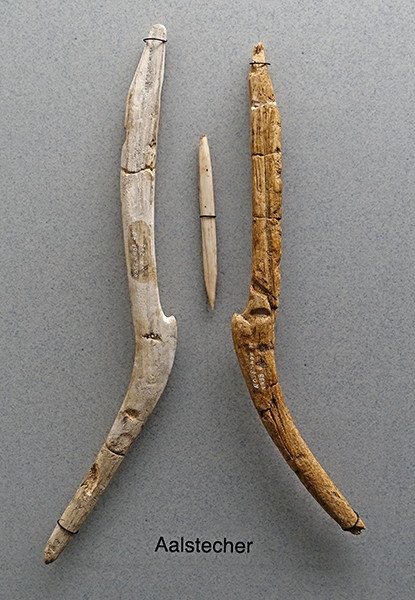

Paddle of elm wood, Duxmoor, Kr. Rendsburg-Eckernförde

Date: 9 000 - 8 000 BP in: University of Groningen (2000)

Hartz and Lübke (2000) give the following information on this paddle:

Duxmoor, Gde. Gettorf LA 26, Kr Rendsburg-Eckernförde

Material: Ash

Fragment

Blade: length 280 mm, width 110 mm, thickness 14 mm

Shaft: length 610 mm, diameter 18 x 19 mm

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Hartz and Lübke (2000), Schwabedissen (1968), Schütrumpf (1968)

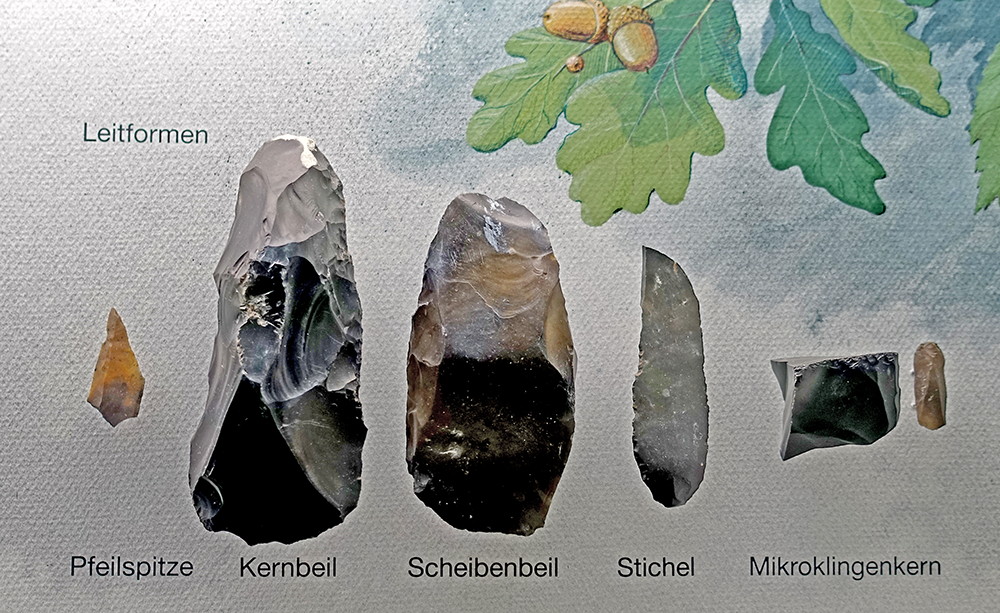

Kongemose Culture

8 000 BP to 7 300 BP

The Kongemose culture was a mesolithic hunter-gatherer culture in southern Scandinavia from 8 000 BP to 7 300 BP, and the origin of the Ertebølle culture. It was preceded by the Maglemosian culture. In the north it bordered on the Scandinavian Nøstvet and Lihult cultures.

Fundamental tools of the Kongemose culture.

(left to right): arrowhead, core hatchet (adze), tranchet axe, burin, microblade core with a microblade.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Wikipedia

Arrowhead.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Kernbeil, or core hatchet.

These were made by striking off very large flakes from a core. The flakes were then retouched to their final form. The cutting edge was positioned so that the tool could be used as an adze to work wood.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: Wikipedia

Scheibenbeil or tranchet axe.

Tranchet axes are large Mesolithic or Neolithic chisel-ended flint artefacts with a sharp straight cutting edge, produced by the removal of a thick flake at a right angle to the main axis of the tool. The technique was used for the manufacture of axes and adzes and allowed a blunted tool to be resharpened by removing another flake from across the edge.

The tranchet technique has two definitions:

1. The removal of a large flat flake from the tip of a biface to form a straight cutting edge from the edge of the tranchet flake scar.

2. The technique used to create or resharpen the ax or adze's cutting edge.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text: https://archaeologywordsmith.com/search.php?q=tranchet

Burin and microblade core.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

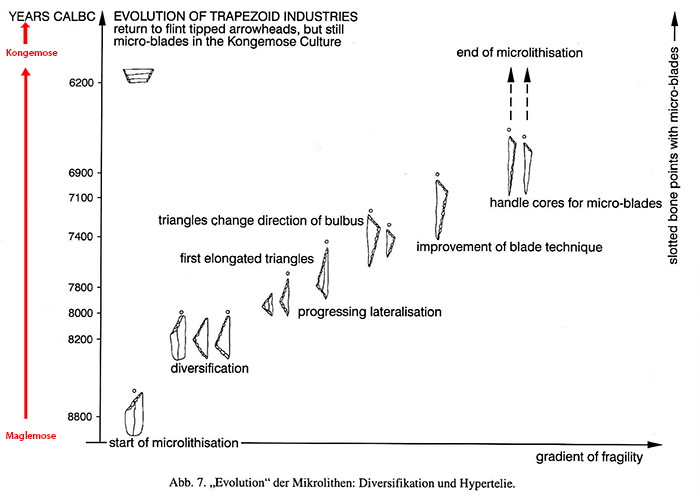

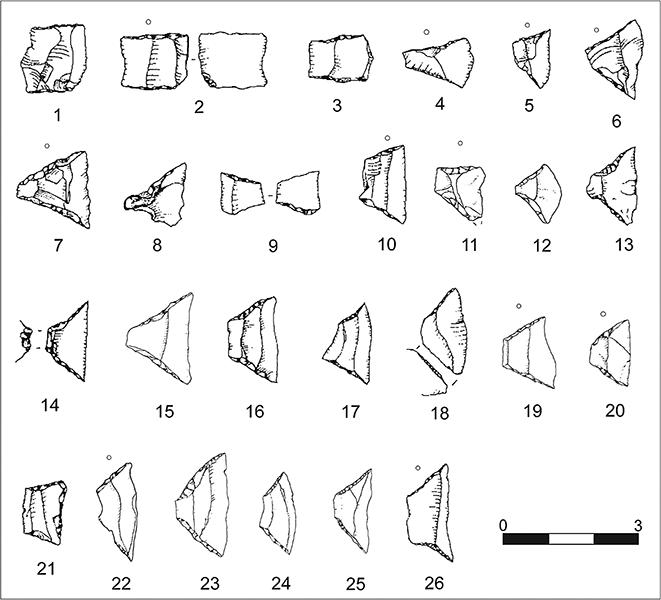

Arrowheads.

( Note that most of these arrowheads are of the transverse or chisel type, made by breaking trapezoids alternately from a blade, which is efficient in terms of time, skill, and materials. This particular selection, apart from a few examples, do not appear to have had much further retouching of the sides to make them concave, and both the wide and narrow edges have been left sharp, although it would have been the narrow edge which was the section of the arrowhead bound to the shaft, with the broader edge being the cutting edge - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Kratzer (scrapers) and Stichel (burins).

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Cores and blades.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Microblades and microblade cores.

( by this time, the advantages of 'small is better' had become very apparent, possibly spurred by the development of the small trapezoidal arrow heads, which were a revolution for the efficient use of time and materials. Increasingly, tools were made only as large as they needed to be - though this trend was matched, paradoxically, by the concomitant development of the techniques for producing very large flakes, much larger than anything previously made, for the production of hatchets and adzes of the Kernbeil (core hatchet) and Scheibenbeil (tranchet axe) type - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

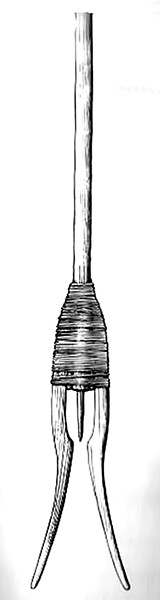

Small blades, set laterally into grooves in arrows and spears, tore wide wounds.

( Such innovations meant that prey went into shock from loss of blood very quickly, and thus did not escape, only to die far from the hunters - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

(left): Recreation of a multi blade spear head.

(right): Original spear head from Wangels Ostholstein, as found.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Map of the Kongemose Culture in Southern Scandinavia.

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

The evolution of microliths, from the Maglemose to the Kongemose cultures.

( my additions in red - Don )

Photo: Bokelmann (1999)

Decorated antler from Lübeck.

( possibly a facsimile - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

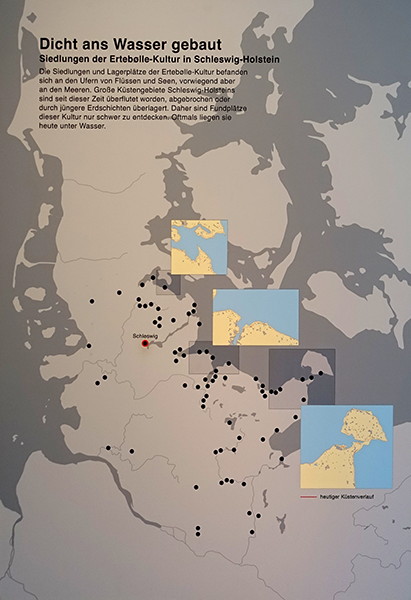

Ertebølle Culture

7 300 BP to 5 950 BP

Ertebølle Culture

In the Ertebølle period the temperature was up to three degrees higher than today, and the sea surface level was correspondingly higher, about 3 metres higher than today. After the kilometer-thick ice-shelf melted away, the land slowly normalised. The area south-west of the line is sinking and the area north-east of the line is rising.

This process is a result of the land once under the ice rising once the weight of the ice is removed, in a process called glacial isostasy. The tectonic plate is tilting up where the ice sheets once weighed it down, and down where there were no ice sheets, since the plate is fairly rigid.

Source and text: http://www.dandebat.dk/eng-dk-historie7.htm#en

Ertebølle Culture

Transverse flint arrow heads.

The typical transverse Ertebølle arrowhead must have been designed to produce a large wound on the prey and thus a substantial loss of blood, so that the hunters could avoid the situation that they hit the animal, yet it runs away with the arrow and lays down to die elsewhere.

( The principle of the transverse arrowhead is simple. A blade with two very sharp sides is struck from a core. The blade is then snapped at an angle, successively, to create trapezoidal shaped microliths. These are often further refined by invasive retouch on both sides to create the typical shape of a transverse arrowhead, as seen here. The advantage is that the hunter need carry only a few sharp 'core' blades, untouched, but carefully wrapped, and create multiple transverse arrowheads as needed. The arrowhead has a very sharp tip, since there is nothing so sharp as the edge of a newly struck flint flake. - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Museum für Archäologie Schloss Gottorf

Additional text adapted from: Sunyol (circa 2009) and http://prehistorics-uk.blogspot.com/2013/02/petit-tranchet-transverse-arrowheads.html

Ertebølle Culture

Microblades.

The Ertebølle culture hunted and fished mostly along the coasts, and used their bows and arrows and other tools to hunt animals, birds, fish and shellfish. The interior of the peninsula was heavily forested, and was apparently less inhabited.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Københavns (Copenhagen) Museum, National Museum of Denmark

Additional text: http://www.dandebat.dk/eng-dk-historie7.htm#en

Ertebølle Culture

Trapezoidal microblades.

My thanks to Thomas Quinn, who pointed out that these blades were used as arrow points, especially for birds and small game.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014