Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

The Ishtar Gate at Babylon

The Ishtar Gate at Babylon

The Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire

Ancient Mesopotamia

King Lists and Artefacts from Ancient Mesopotamia

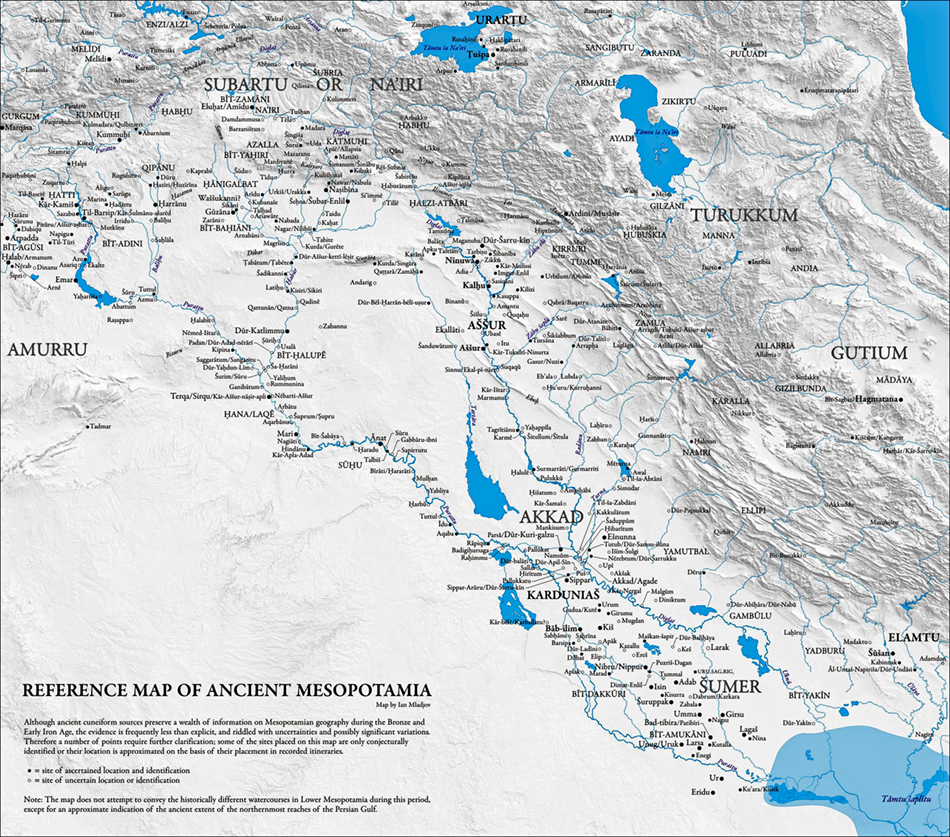

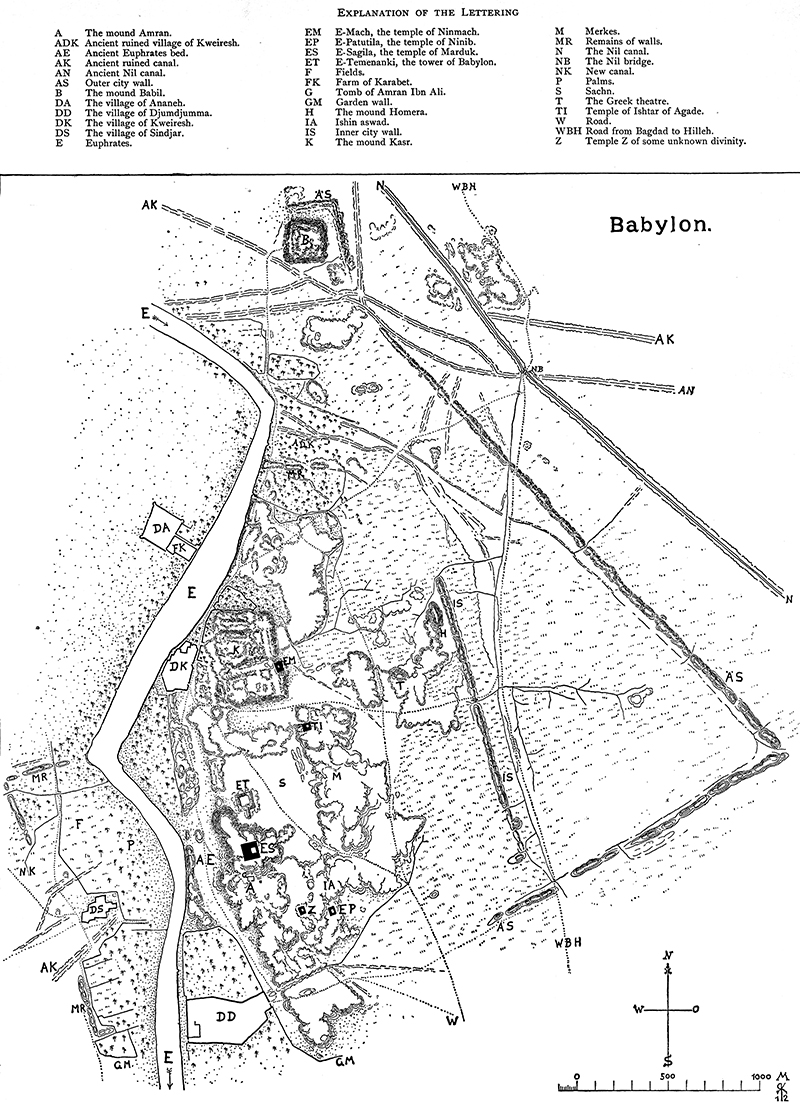

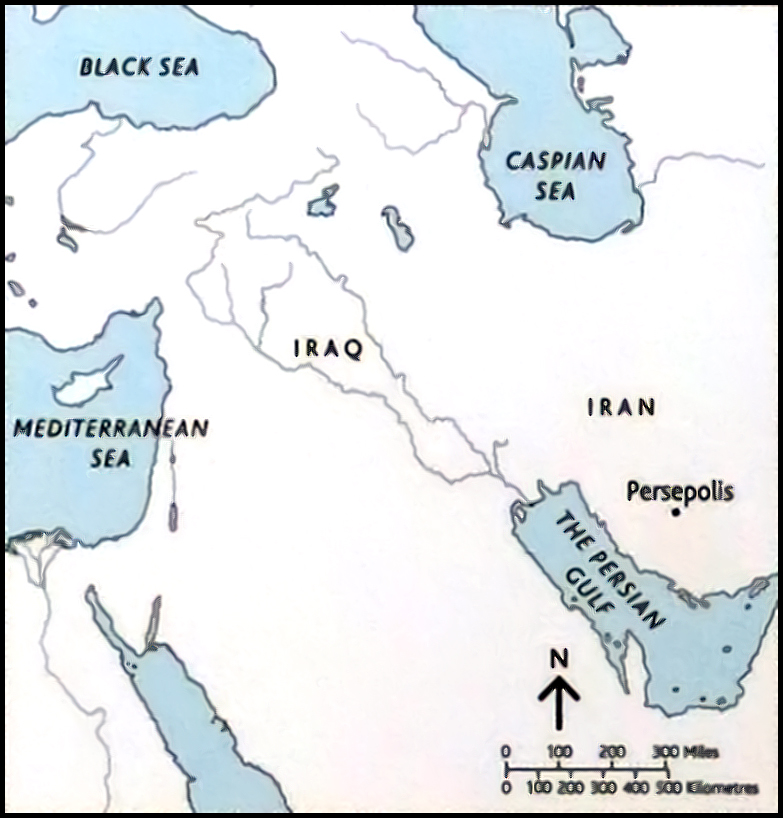

The historical region of Mesopotamia included present-day Iraq and parts of present-day Iran, Kuwait, Syria and Turkey

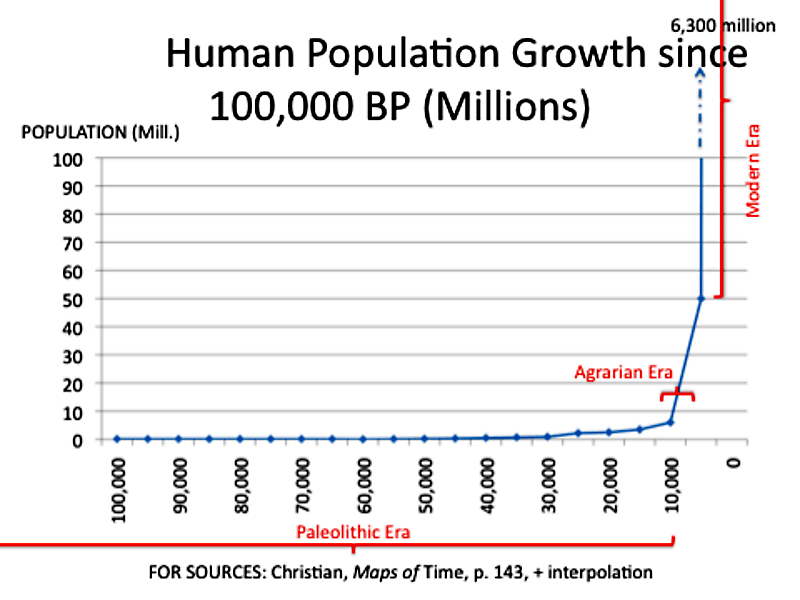

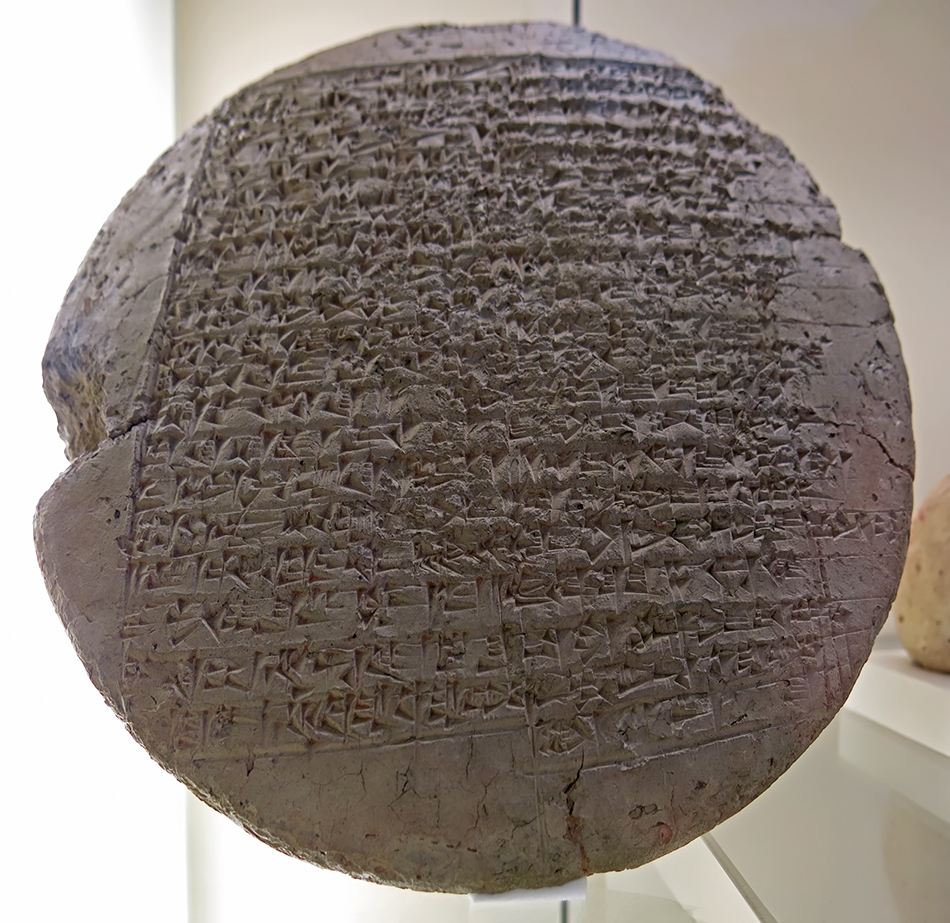

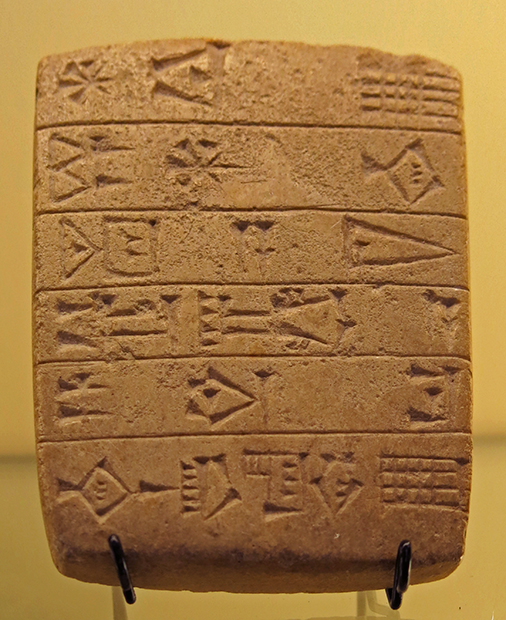

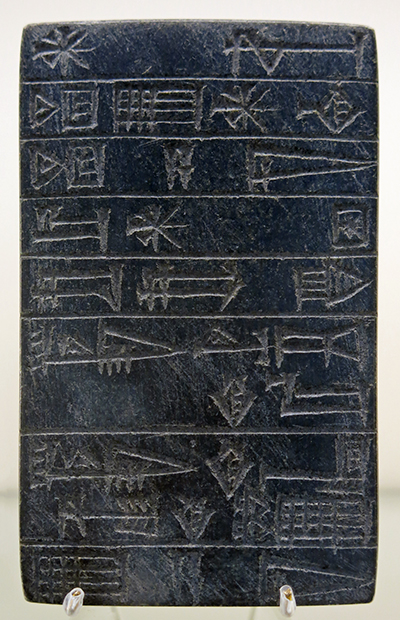

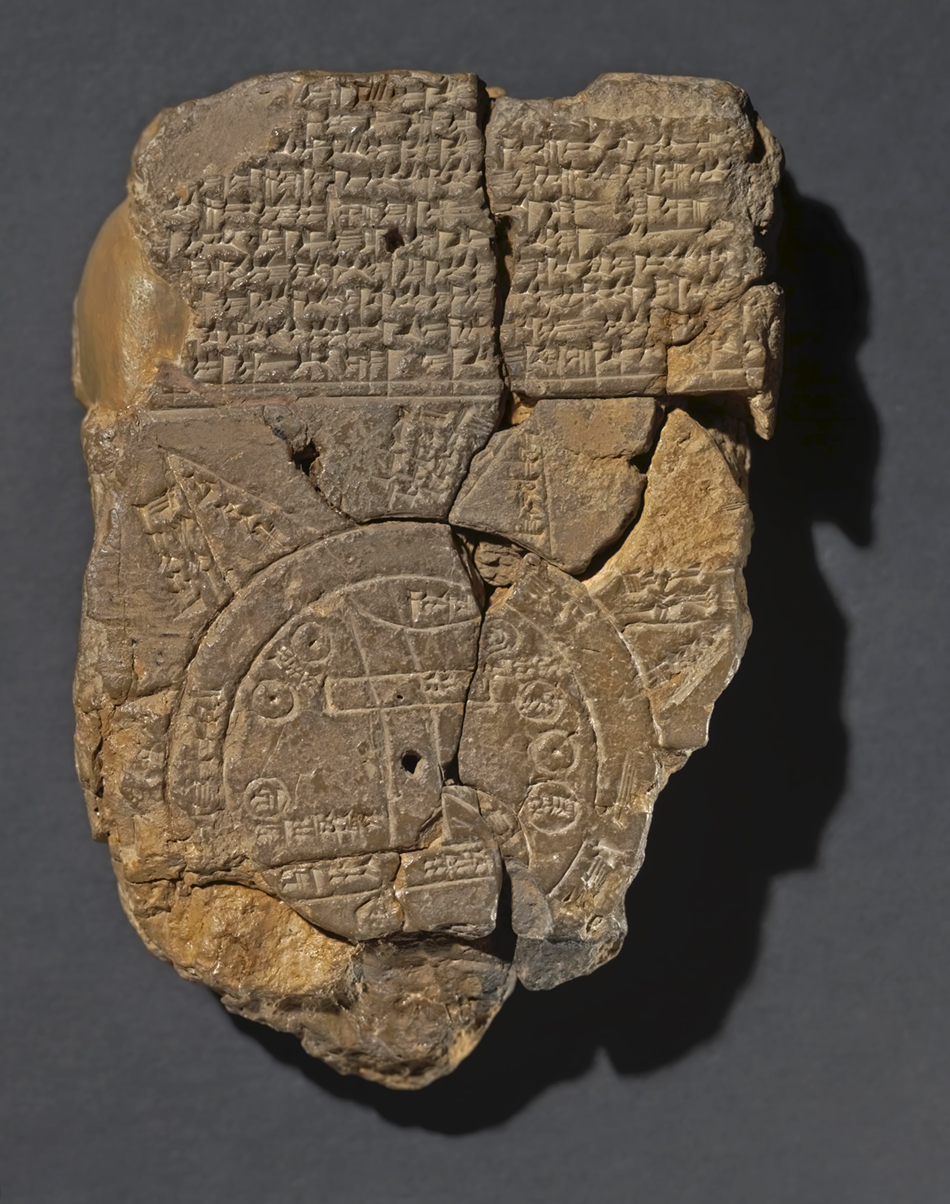

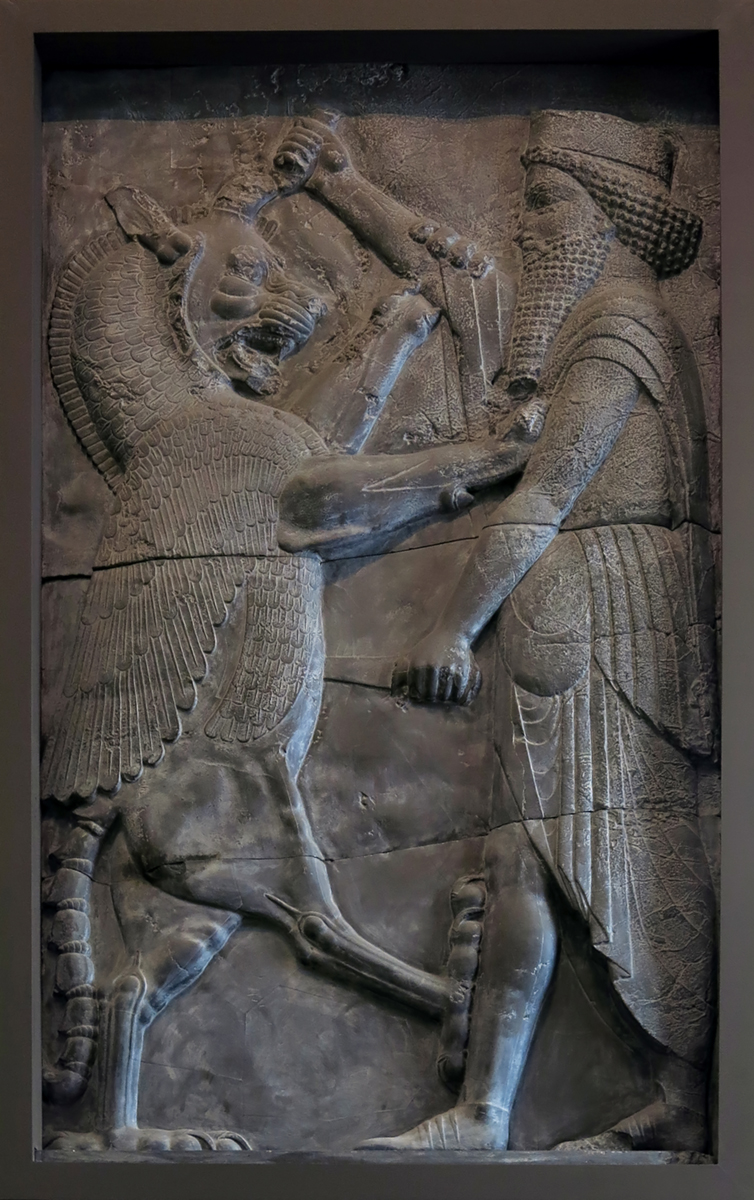

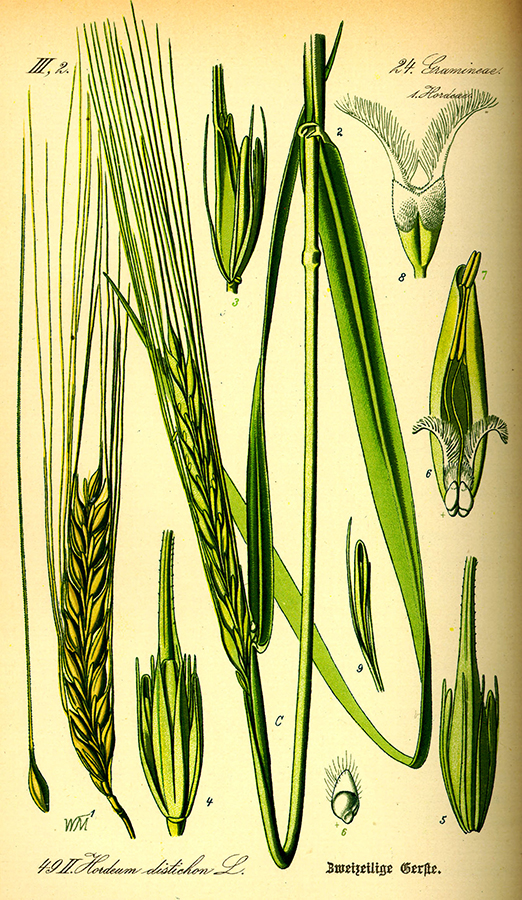

Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10 000 BC. It has been identified as having inspired some of the most important developments in human history, including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops, and the development of cursive script, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture. It is recognised as the cradle of some of the world's earliest civilisations.Sumer is the earliest known civilisation in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic (Copper) and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of civilisation in the world. Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, the surplus from which enabled them to form urban settlements. Proto-writing dates back before 3 000 BC. The earliest texts come from the cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, and date to between 3 500 BC and 3 000 BC.

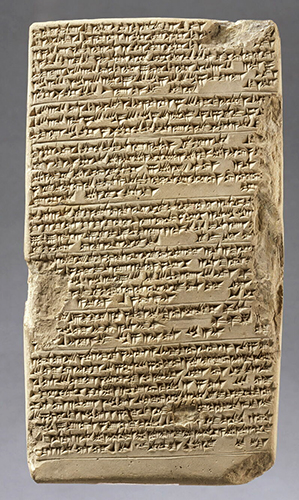

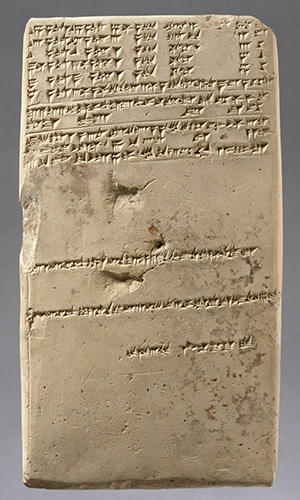

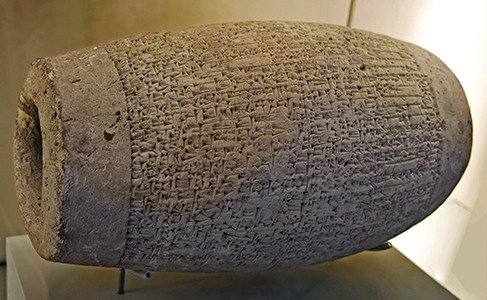

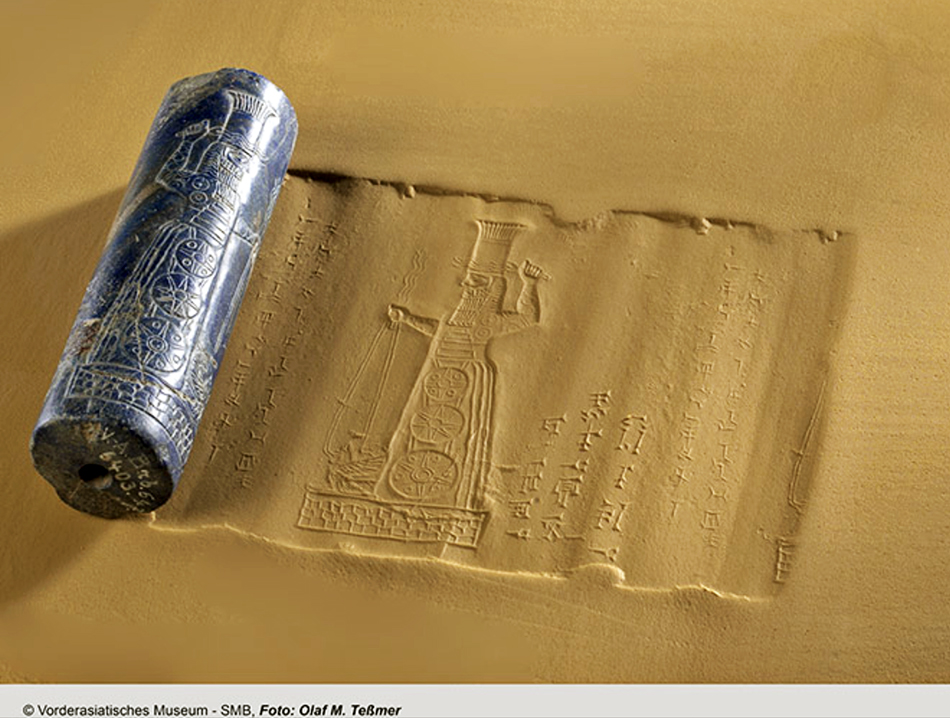

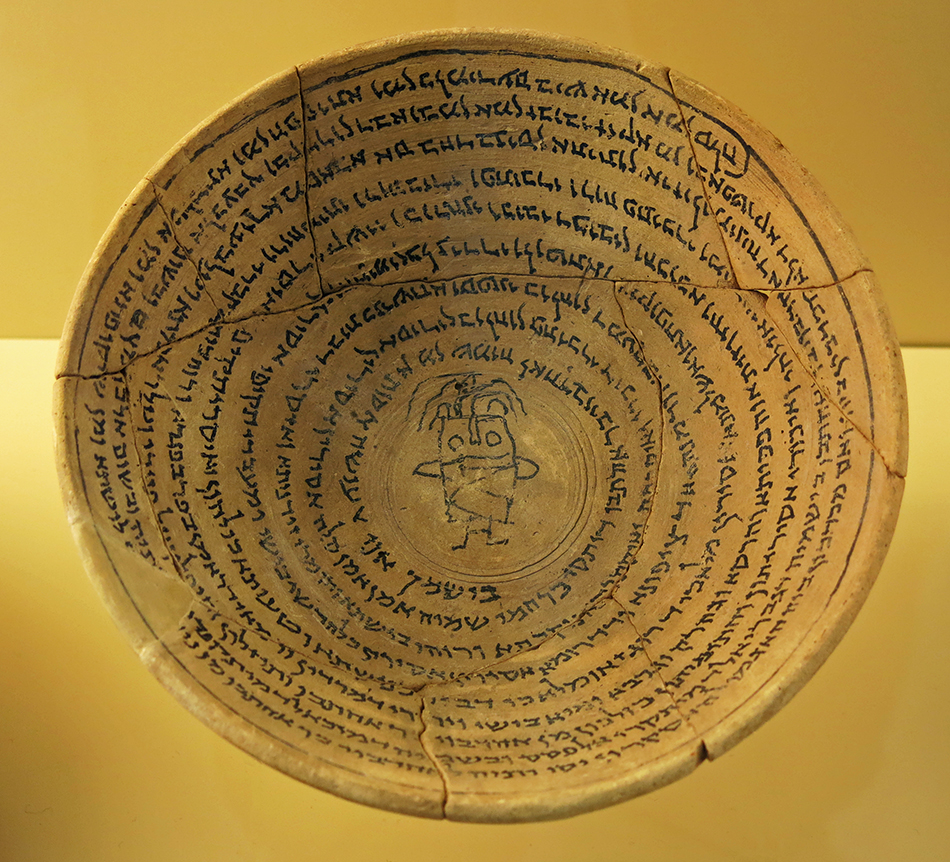

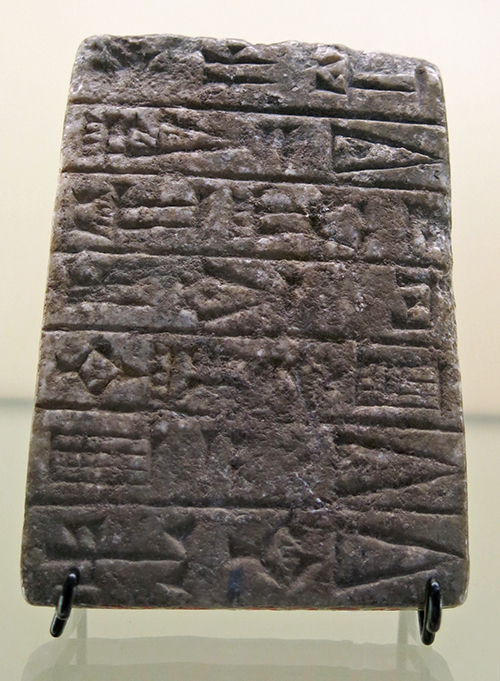

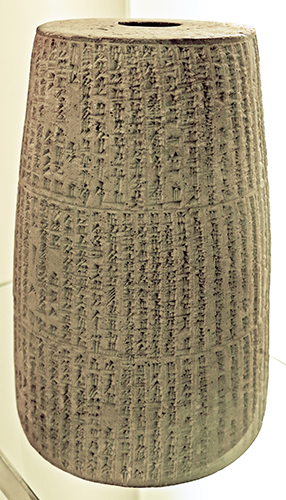

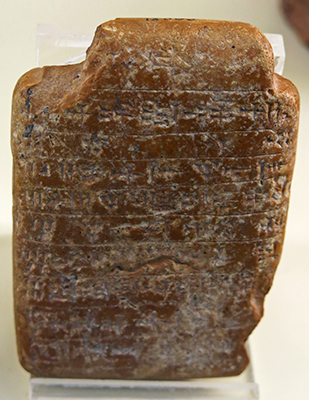

The Sumerian language was the first to be recorded on clay tablets, with the words being recorded as syllables rather than using an alphabet. Sumerian did not survive, but the cuneiform script was taken up by other groups, and continued to develop after the Sumerians disappeared.

In particular the Assyrians, who used the Akkadian language, also used cuneiform script on clay tablets, and their language formed part of many other languages which either descended from it, or borrowed words from Akkadian.

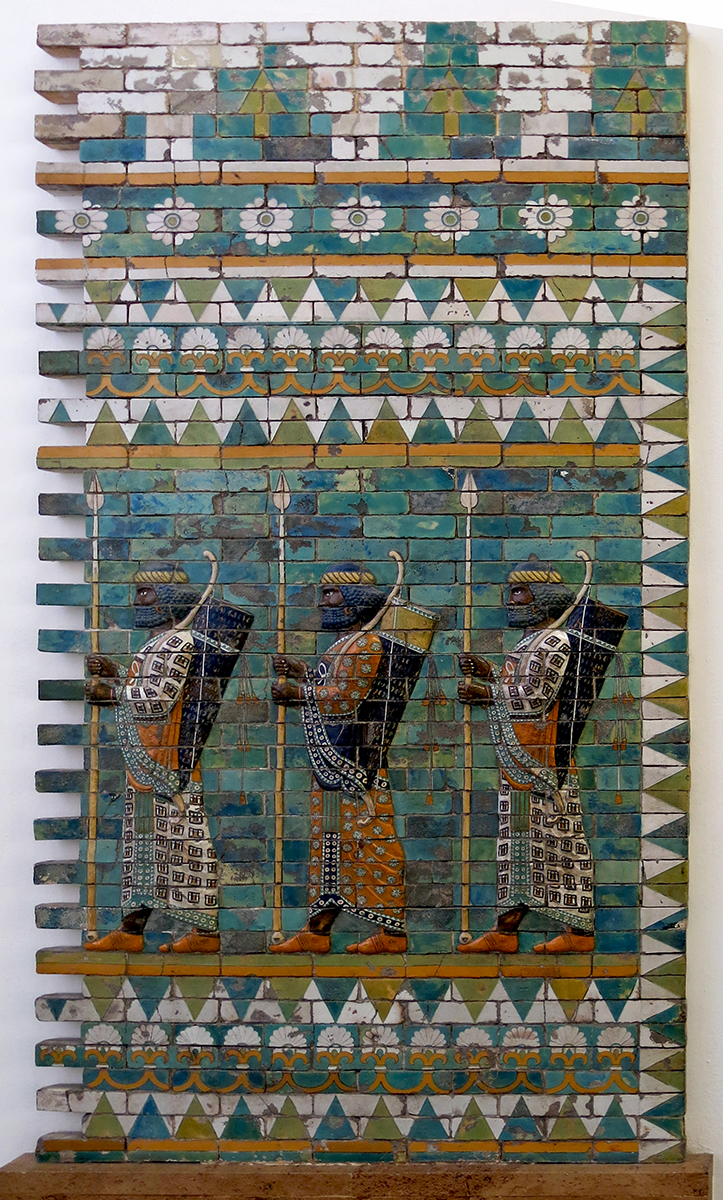

The Sumerians and Akkadians (including the Assyrians and Babylonians) originating from different areas in present-day Iraq, dominated Mesopotamia from the beginning of written history (circa 3 100 BC) to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, when it was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire, also known as the First Persian Empire.

The Achaemenid Empire was founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC , and stretched from Eastern Macedon, Thrace, Libya and Northern Egypt in the west, to Central Asia and the Indus Valley to the east. It occupied an area of 5.5 million square kilometres, and was the largest empire the world had ever seen up to that time,

Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10 000 BC. It has been identified as having inspired some of the most important developments in human history, including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops, and the development of cursive script, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture. It is recognised as the cradle of some of the world's earliest civilisations.

Text above: adapted from Wikipedia

Important notice: Establishing reliable dates for Mesopotamian kings, particularly before the 1st millennium BC, is a major challenge due to a reliance on fragmented, often non-contemporary, or ideologically driven records, rather than a continuous, scientifically fixed calendar. The primary problem lies in bridging the gap between a 'floating chronology' (knowing the sequence of rulers) and an absolute chronology (matching them to calendar years).

The dates presented here are drawn from multiple sources, many of which differ significantly between two or more otherwise apparently reliable sources, or contradict one another (or are even self contradictory!). I have attempted to bring some order to this confusion, but in certain cases establishing reliable dates is simply not possible. Many or perhaps most of the dates given in the table below are at best very approximate. Treat the dates with great caution. Caveat emptor.

| Mesopotamian Chronology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Mesopotamia | |||

| Early Dynastic Period | |||

| Gilgamesh of Uruk | 2700 BC | Gilgamesh was likely a historical king of Uruk who reigned around the early 3rd millennium BC. Inscriptions credit him with building the great walls of Uruk. He was the protagonist of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest known epic poem. | |

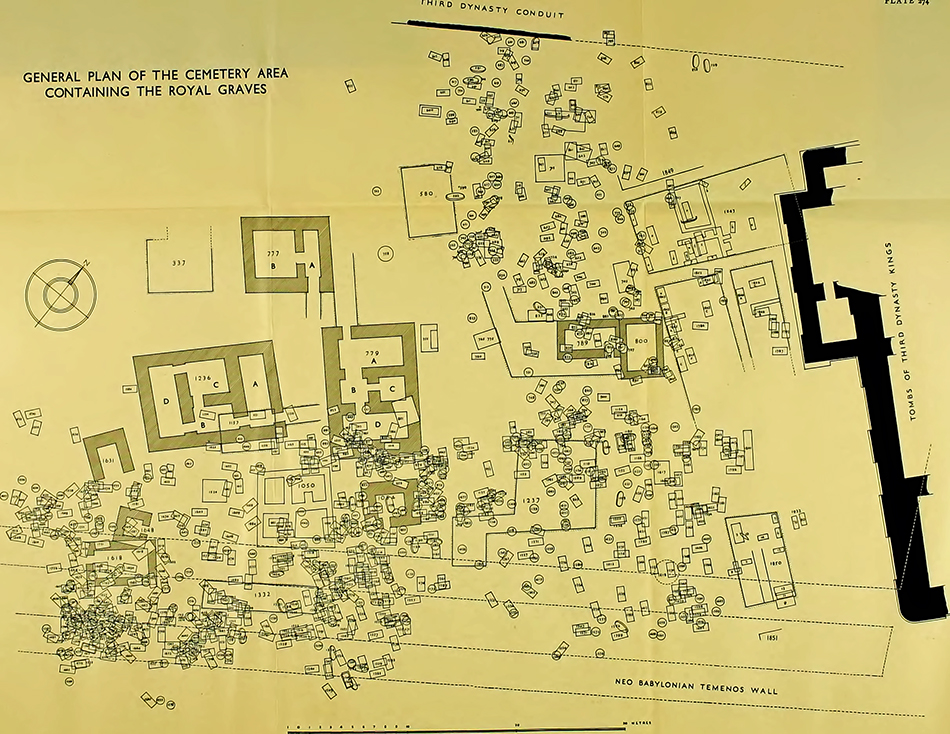

| Mesanepada of Ur | 2450 BC | Mesannepada was the first king listed for the First Dynasty of Ur on the Sumerian king list. He is recorded as having ruled for 80 years, after overthrowing Lugal-kitun of Uruk. In one of his seals, found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, he is also described as king of Kish. | |

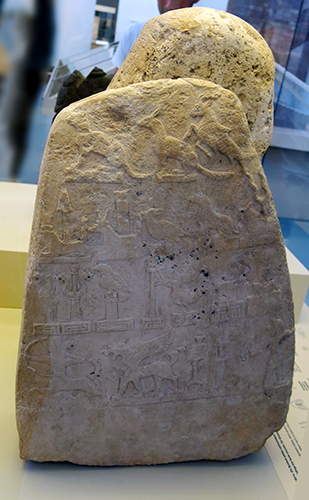

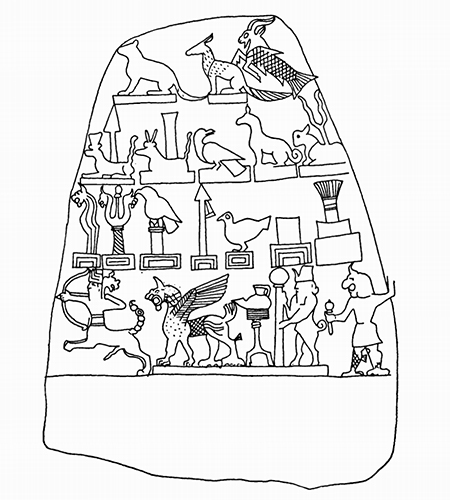

| Eannatum of Lagash | 2455 BC | Eannatum was a king of Lagash (now Tell al Hiba) around the mid-25th century BC (ca. 2455–2425 BC), renowned for establishing the first significant Mesopotamian empire by expanding his city-state's power through conquest, particularly against its rival, the city of Umma, and extending Lagash's influence as far as Elam and the Persian Gulf. His reign is documented by monuments like the Stele of the Vultures, which depicts his military triumphs and the brutal policy he employed against enemies. | |

| Enannatum of Lagash | 2425 BC | Enannatum I, son of Akurgal, succeeded his brother Eannatum as Ensi (ruler, king) of Lagash. He fought off several attacks by the Kingdom of Umma, an important Sumerian city-state in southern Mesopotamia. | |

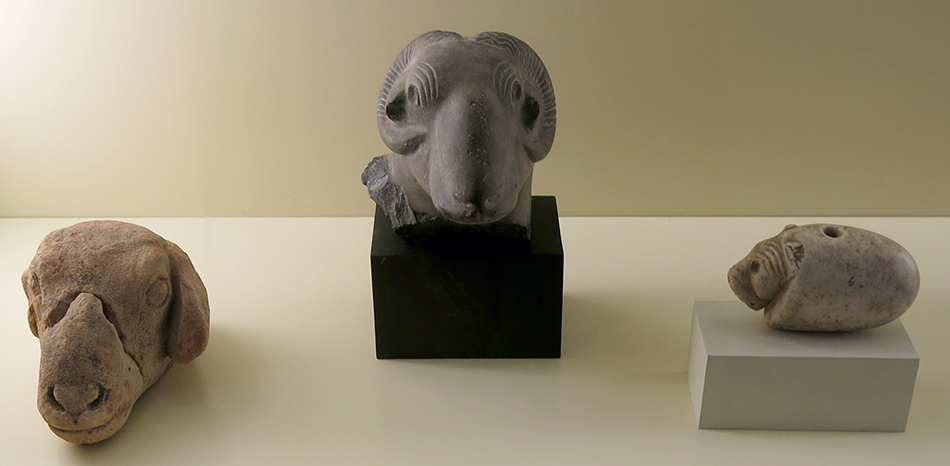

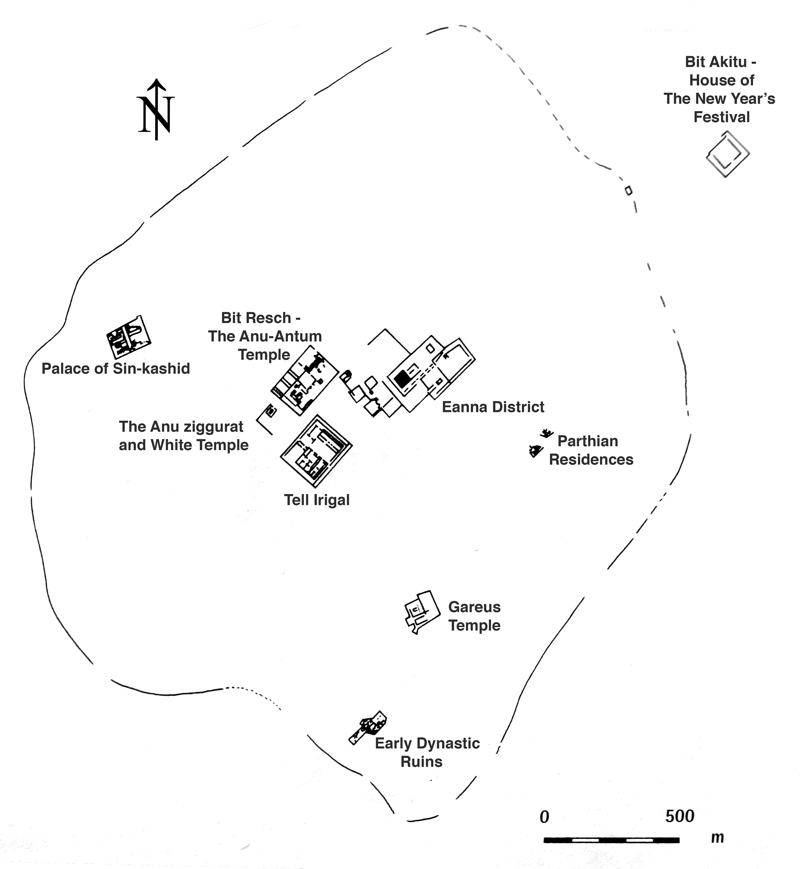

| Urukagina of Lagash | 2340 BC | Urukagina (Uruk-Agina, Uruinimgina) was the first known social reformer of the ancient world. He was the last independent king of Lagash. The series of reforms he effected as king in Lagash were intended to correct economic abuses perpetrated on the general population by those of the priestly class. His reforms are known from inscriptions left on three clay cones and an oval-shaped plaque found at the site of ancient Lagash in 1878. The prefix Uruk was derived from the city Uruk, one of the world's first major cities, which had became a significant urban centre by 3200 BC, and after which he was named. | |

| Lugalzagesi of Umma | 2350 BC | Lugalzagesi of Umma (died ca 2334 BC) was the last Sumerian king before the conquest of Sumer by Sargon of Akkad and the rise of the Akkadian Empire, and was considered as the only king of the third dynasty of Uruk, according to the Sumerian King List. Initially, as king of Umma, he led the final victory of Umma in the generation-long conflict with the city-state Lagash for the fertile plain of Gu-Edin. Following up on this success, he then united Sumer briefly as a single kingdom. | |

| Dynasty of Lagash | |||

| Ur-Nanshe | 2520 BC - 2500 BC | Ur-Nanshe was the first king of the First Dynasty of Lagash in the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period III. He is known through inscriptions to have commissioned many building projects, including canals and temples, and defending Lagash from its rival state Umma. He was probably not from royal lineage. He was the father of Akurgal, who succeeded him, and grandfather of Eannatum. | |

| Akurgal | 2460 BC | During Akurgal's reign, a border conflict pitted Lagash against Umma. These borders between Umma and Lagash had been fixed in ancient times by Mesilim, king of Kish, who had drawn the borders between the two states in accordance with the oracle of Ishtaran, invoked as intercessor between the two cities. He had two sons, who both became important rulers of Lagash after him, Eannatum and Enannatum I, and successfully repelled Umma's encroachment. | |

| Eannatum | 2450 BC | Eannatum established one of the first verifiable empires in history, subduing Elam and destroying the city of Susa, and extending his domain over the rest of Sumer and Akkad. One inscription found on a boulder states that Eannatum was his Sumerian name, while his 'Tidnu' (Amorite) name was Lumma. He conquered all of Sumer, including Ur, Nippur, Akshak (controlled by Zuzu), Larsa, and Uruk. He entered into conflict with Umma, waging a war over the fertile plain of Gu-Edin. He personally commanded an army to subjugate the city-state, and vanquished Ush, the ruler of Umma, finally making a boundary treaty with Enakalle, successor of Ush, as described in the Stele of the Vultures and in the Cone of Entemena. Enannatum had a son named Meannesi, who is known for dedicating a statue for the life of his father and mother. He has two other sons, Lummatur and Entemena, the latter succeeding him to the throne. His wife was named Ashumen. | |

| Enannatum I | 2425 BC - 2410 BC | Enannatum I, son of Akurgal, succeeded his brother Eannatum as Ensi (ruler, king) of Lagash. During his rule, Umma once more asserted independence under its ensi Ur-Lumma, who attacked Lagash unsuccessfully. After several battles, Enannatum I finally defeated Ur-Lumma. Ur-Lumma was replaced by a priest-king, Il, who also attacked Lagash. Enannatum I of Lagash was succeeded by his son Entemena around 2400 BC. Entemena re-established the power of Lagash by defeating the ruler of Umma, Il, following the struggles of his father's reign. Enannatum I likely died or was mortally wounded in battle against the city of Umma, leaving Entemena to finish the conflict. Entemena ruled for at least 19 years and restored the prestige of the First Dynasty of Lagash. | |

| Entemena | 2404 BC - 2391 BC | Enannatum I of Lagash was succeeded by his son Entemena. Entemena re-established the power of Lagash by defeating the ruler of Umma, Il, following the struggles of his father's reign. Enannatum I likely died or was mortally wounded in battle against the city of Umma, leaving Entemena to finish the conflict. Entemena ruled for at least 19 years and restored the prestige of the First Dynasty of Lagash. | |

| Enannatum II | 2391 BC – 2376 BC | Entemena, the ruler (Ensi) of Lagash, was succeeded by his son Enannatum II. Enannatum II was the last known ruler of the first dynasty of Lagash before its decline and eventual fall to the city of Umma. Enannatum II was the final ruler of the direct line of Ur-Nanshe, after which the influence of Lagash weakened. Enannatum II, the last member of the house of Ur-Nanshe to rule Lagash, was succeeded by a priest named Enentarzi. Enentarzi took the throne following the decline of the dynasty's power. He was later succeeded by either Enlitarzi or Lugalanda. | |

| Enentarzi | 2376 BC – 2372 BC | Enentarzi was an Ensi (governor) of Lagash. He was originally a chief-priest of Lagash for the god Ningirsu. He succeed Enannatum II who only had a short reign and was the last representative of the house of Ur-Nanshe. It seems that the power of Lagash waned at this point, and that other territories such as Umma ('Gishban') and Kish prevailed. Enentarzi probably ruled for at least 4 years. An inscription records that 600 Elamites came to plunder Lagash during the rule of Enentarzi, but that they were repelled. He was succeeded by either a priest named Enlitarzi, or his son Lugalanda. | |

| Lugalanda | 2372 BC – 2370 BC | Lugalanda succeeded Enentarzi as the ruler of Lagash. As the son of Enentarzi, Lugalanda took over as a high priest and king (known as an ensi) during the Early Dynastic III period, though he is primarily noted for his corrupt rule. All documents mentioning the reign of Lugalanda describe him as a wealthy but corrupt king. They state his reign was a time of great corruption and injustice against the weak. Inscriptions state that the king confiscated approximately 650 Morgen (around 6.5 sq km) of land. Lugalanda appointed officials unjustly, widely overtaxed civilians and misused properties all for the sake of his personal gain. | |

| Urukagina | 2370 BC – 2360 BC | Urukagina was a Sumerian king who ruled the city-state of Lagash during the 24th century BC He was the last ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Lagash and is renowned for implementing some of the earliest recorded legal reforms, aiming to reduce corruption and social inequality. He ruled for approximately seven years. He assumed power following the reign of Lugalanda, who continued to live for 4 or 5 years after Urukagina's ascension. His reforms, often called the 'Code of Urukagina' or 'Reforms of Urukagina' addressed high taxes, abuse of power by officials, and protected the poor, widows, and orphans. The reforms are often celebrated as the first, albeit indirect, examples of government reforms in written history. | |

| Dynasty of Akkad (Agade) | |||

| Sargon | 2340 BC - 2285 BC | Sargon of Akkad (died ca 2279 BC), also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BC. He is sometimes identified as the first person in recorded history to rule over an empire. He was the founder of the Sargonic or Old Akkadian dynasty, which ruled for about a century after his death until the Gutian conquest of Sumer. The Sumerian King List makes him the cup-bearer to King Ur-Zababa of Kish before becoming king himself. His empire, which he ruled from his archaeologically capital, Akkad, is thought to have included most of Mesopotamia and parts of the Levant, Hurrian and Elamite territory. Akkad was a region and a capital city in ancient Mesopotamia, located in modern-day central Iraq, in the general confluence area of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. While the precise location of the city of Akkad has never been confirmed by archaeological evidence, it is generally thought to be east of Babylon. | |

| Rimush | 2384 BC - 2275 BC | Rimush was the second king of the Akkadian Empire. He was the son of Sargon of Akkad. According to the Sumerian King List, his reign lasted nine years (though variant copies read seven or fifteen years). To some extent, his reign was typical of a ruler of Mesopotamia with proper attention paid to the various deities and their temples. A number of his votive offerings have been found in excavated temples in several Mesopotamian cities including Ur, Sippar, Khafajah, and Brak. After the conquest of Elam, he dedicated 30 mana (a mana was about a half kilogram) of gold, 3 600 mana of copper, and 360 slaves to Enlil, the chief deity of Nippur. Most of his short reign was taken up consolidating the empire created by his father, Sargon, first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. This empire stretched in the west to Syria in places like Tell Brak and Tell Leilan, to the east in Elam and associated polities in that region, to southern Anatolia in the north, and to the 'lower sea' in the south encompassing all the traditional Sumerian powers like Uruk, Ur, and Lagash. All of these political entities had long histories as independent powers and would periodically re-assert their interests throughout the lifetime of the Akkadian Empire. | |

| Manishtushu | 2270 BC - 2255 BC | Manishtushu was the third king of the Akkadian Empire, reigning 15 years ca. 2270 BC until his death ca 2255 BC. He was the son of Sargon the Great, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, and he was succeeded by his son, Naram-Sin. He became king after the death of his brother Rimush. Manishtushu, freed of the rebellions of his brother's reign, led campaigns to distant lands. According to a passage from one of his inscriptions, he led a fleet down the Persian Gulf where 32 kings allied to fight him. Manishtushu was victorious and consequently looted their cities and silver mines, along with other expeditions to kingdoms along the Persian Gulf. He also sailed a fleet up the Tigris River that eventually traded with 37 other nations, conquered the city of Anshan in Elam, and rebuilt the destroyed temple of Inanna in Nineveh ca 2260 BC. | |

| Naram-Sin | 2255 BC - 2218 BC | Naram-Sin was the grandson of King Sargon of Akkad. Under Naram-Sin, the kingdom reached its maximum extent. He was the first Mesopotamian king known to have claimed divinity for himself, taking the title 'God of Akkad'. His military strength was strong as he crushed revolts and expanded the kingdom to places like Turkey and Iran. During his reign Naram-Sin increased direct royal control of its city-states. He maintained control over the various city-states by the simple expedient of appointing some of his many sons as key provincial governors, and his daughters as high priestesses. He also reformed the scribal system. | |

| Shar-kali-sharri | 2218 BC - 2193 BC | Shar-Kali-Sharri succeeded his father Naram-Sin. At the time, one of the primary duties of the ruler of Mesopotamia was the maintenance of the Ekur temple of the chief god Enlil. Work on the temple, initiated by Naram-Sin, was completed by Shar-Kali-Shari. So important was this process that it was featured in seven of his year names, even naming the general appointed to lead the task, Puzur-Eshtar. Inscribed bricks of Shar-Kali-Shari were found during the excavation of Nippur. According to the Sumerian King List and later literary compositions, after Shar-Kali-Sharri's death in ca 2193 BC., the region fell into anarchy, with no king able to achieve dominance for long. The king list states: 'Then who was king? Who was not the king? Igigi, Imi, Nanum, Ilulu: four of them ruled for only 3 years.' Akkad then resumed some resemblance of order for a time with the 21-year reign of Dudu followed by the 15-year reign of Shu-turul. | |

| Dudu | 2189 BC - 2168 BC | Dudu was a 22nd-century BC king of Akkad. He became king after a period of apparent anarchy that had followed the death of Shar-Kali-Sharri. The king list mentions four other figures who had been competing for the throne during a three-year period after Sharkalisharri's death. There are no other surviving records referencing any of these competitors, but a few artefacts with inscriptions confirming Dudu's rule over a reduced Akkadian Empire. Given activity at Umma and Girsu, and at Apiak whose location is unknown but which lay near the Tigris river to the East of Nippur, the Akkadian Empire maintained some level of control to the south at least. The find of a seal at Adab, lying further East that Apiak, of a servant of Dudu supports this view. His inscriptions present him simply as 'King of Akkad' and was described as 'Dudu the mighty, king of Agade: Amar-šuba the scribe (is) his servant. This was a seal inscription of Amar-šuba found at Bismaya. He also seems to have campaigned against former Akkadian subjects to the south, including Girsu, Umma (where the governor of Lagash appointed by Shar-Kali-Sharri, Puzer-Mama, had declared independence at the end of that rule) and possibly Elam. | |

| Shu-turul | 2168 BC - 2154 BC | Shu-turul held sway over a greatly reduced Akkadian territory that included Kish, Tutub, Nippur, and Eshnunna. The Diyala River also bore the name 'Shu-durul' at the time. A few inscriptions in his name are known. One, on an administrative clay sealing found at Kish reads: 'Šu-Turul the mighty, king of Agade' The king list asserts that Akkad was then conquered, the Akkadian Empire collapsed, and the hegemony returned to Uruk following his reign. With Akkad's collapse, the Gutians, who had established their capital at Adab, became the regional power, though several of the southern city-states such as Uruk, Ur, and Lagash also declared independence around this time. | |

| Third Dynasty of Ur | |||

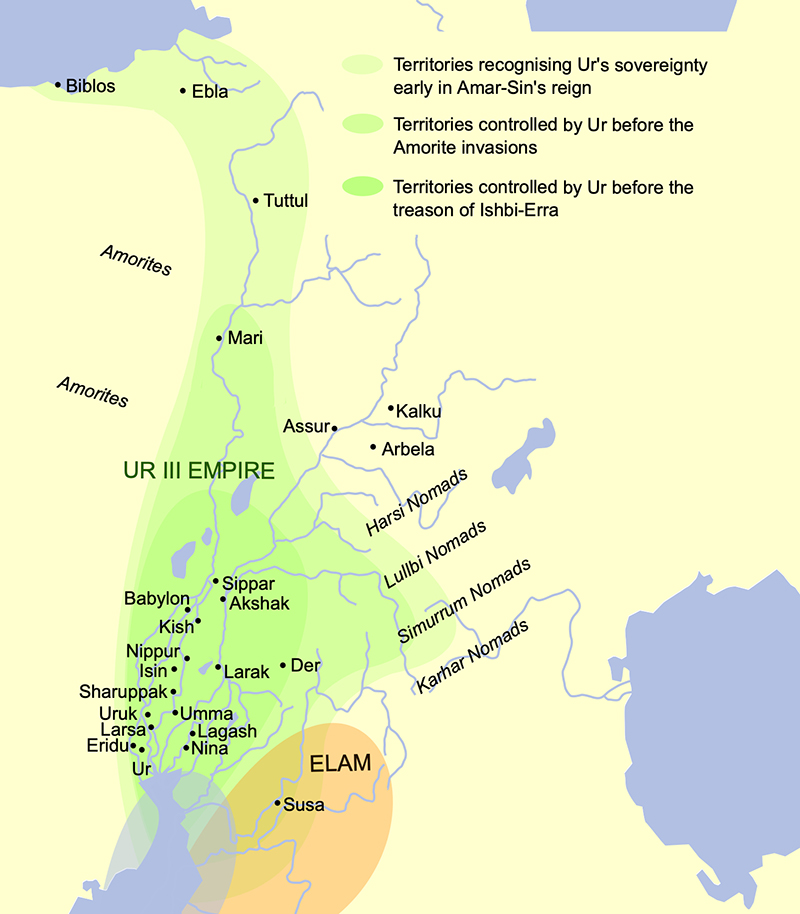

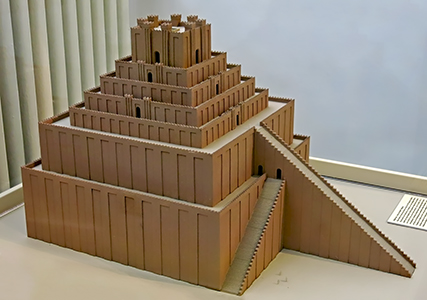

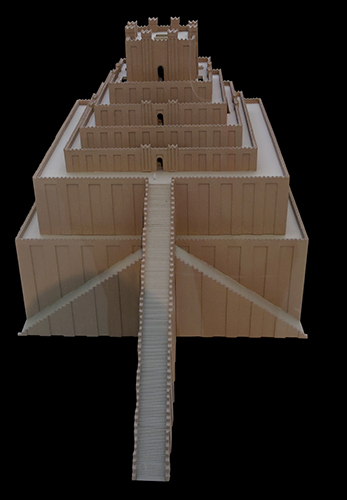

| Ur-Nammu | 2112 BC - 2094 BC | Ur-Nammu founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries of Akkadian and Gutian rule. Though he built many temples and canals his main achievement was building the core of the Ur III Empire via military conquest, and Ur-Nammu is chiefly remembered today for his legal code, the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known surviving example in the world. Note, however, that the code is now believed to have been created by his son Shulgi, though it is still known as the Code of Ur-Nammu. He held the titles of 'King of Ur, and King of Sumer and Akkad'. Among his military exploits were the conquest of Lagash and the defeat of his former masters at Uruk. He was eventually recognised as a significant regional ruler of Ur, Eridu, and Uruk at a coronation in Nippur, and is believed to have constructed buildings at Nippur, Larsa, Kish, Adab, and Umma. He was known for restoring the roads and general order after the Gutian period. Ur-Nammu was also responsible for ordering the construction of a number of ziggurats, including the Great Ziggurat of Ur. It has been suggested, based on a much later literary composition, that he was killed in battle after he had been abandoned by his army. | |

| Shulgi | 2094 BC - 2046 BC | Shulgi of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years. His accomplishments include the completion of construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, begun by his father Ur-Nammu. On his inscriptions, he took the titles 'King of Ur', 'King of Sumer and Akkad', adding 'King of the four corners of the universe' in the second half of his reign. Shulgi was the son of Ur-Nammu king of Ur and his queen consort Watartum. Shulgi led a major modernisation of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He improved communications, reorganised the army, reformed the writing system and weight and measures, unified the tax system, and created a strong bureaucracy. He also wrote a law code, now known as the Code of Ur-Nammu because it was originally thought to have been authored by Ur-Nammu. He also built or rebuilt numerous temples throughout the empire. Shulgi is best known for his extensive revision of the scribal school's curriculum. Although it is unclear how much he actually wrote, there are numerous praise poems written by and directed towards this ruler. He had proclaimed himself a god by his 21st regnal year, and was recognised as such by the whole of Sumer and Akkad. | |

| Amar-Sin | 2046 BC - 2038 BC | Amar-Sin, King of the Neo-Sumerian Empire, was the third ruler of the Ur III Dynasty. He succeeded his father Shulgi. His name may be translated as 'bull calf of the moon-god'. Amar-Sin is known to have campaigned against Elamite rulers such as Arwilukpi of Marhashi, and the Ur Empire under his reign extended as far as the northern provinces of Lullubi and Hamazi, with their own governors. He also ruled over Assur through the Akkadian governor Zariqum, as confirmed by his monumental inscription. Amar-Sin's reign is notable for his attempt at regenerating the ancient sites of Sumer. He apparently worked on the unfinished ziggurat at Eridu. The administrative documentation from Amar-Sin's reign suggests that in his final years, he was confronted with some internal strife, and it is likely that his brother, Shu-Sin, was behind an effort to ovethrow him. It is unclear if Amar-Sin was assassinated during this period, or if he died of natural causes. | |

| Shu-Sin | 2037 BC - 2029 BC | Shu-Sin was the brother of the previous king, and also reigned for nine years. He reinstated members of families ousted by his predecessor as governors, which is another indication of the tensions running through the top of the state. He, in turn, had to assert his authority in the northern and eastern peripheries (Shimanum, Zabshali, Shimashki). The tribute collected from these regions seems to arrive less regularly, a sign of a weakening of the King of Ur's influence. The most threatening danger came from the northwest, due to the incursions of Amorite groups. To counter this, Shu-Sîn reinforced the defensive system established by Shulgi by building a new wall. During the latter part of the reign, much of the power appears to have been in the hands of Chancellor Aradmu. | |

| Ibbi-Sin | 2028 BC - 2004 BC | Ibbi-Sin was probably the son of Shu-Sin, and reigned for twenty-four years during which the kingdom disintegrated. The archives of the major administrative centres of the central regions dried up from the beginning of his reign (after the third year). Several military campaigns were conducted against the political entities located on the eastern margins of the kingdom (Anshan, Huhnur, Susa) which had taken their autonomy, but they were few in number and ceased after his fourteenth year of reign. Subsequently, the provinces close to the centre also became independent: this is well known for Eshnunna and especially Isin under the leadership of Ishbi-Erra, a renegade governor. The incursions of the Amorite tribes are increasingly violent, while a situation of food shortage broke out. | |

| Dynasty of Isin | |||

| Ishbi-Erra | 2018 BC - 1985 BC | The Dynasty of Isin was the final ruling dynasty listed on the Sumerian King List (SKL). The dynasty was situated within the ancient city of Isin. The Dynasty of Isin is often associated with the nearby and contemporary dynasty of Larsa. While in many ways this dynasty emulated that of the preceding one, its language was Akkadian as the Sumerian language had become moribund in the latter stages of the Third Dynasty of Ur. At the outset of his career, Ishbi-Erra was an official working for Ibbi-Sin, the last king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He went on to win decisive victories against the Amorites in his 8th year and the Elamites in his 16th years. He founded fortresses and installed city walls, but only one royal inscription is extant. | |

| Shu-ilishu | 1984 BC - 1975 BC | Shu-Ilishu rebuilt the walls of his capital city Isin. He was a great benefactor of Ur (beginning the restoration which was to continue through his successors Iddin-Dagān and Išme-Dagan). Shu-Ilishu built a monumental gateway and recovered an idol representing Ur's patron deity (Nanna, god of the moon) which had been expropriated by the Elamites when they sacked the city. | |

| Iddin-Dagan | 1974 BC - 1954 BC | Iddin-Dagan is best known for his participation in the sacred marriage rite and the sexually explicit hymn that described it. The continued fecundity of the land was ensured by the annual performance of the sacred marriage ritual in which the king impersonated the god Dumuzi-Ama-ušumgal-ana and a priestess played the role of Inanna. A hymn describing Iddin-Dagan's performance of this ritual in ten sections (Kiruḡu) indicates that this ceremony involved a procession of: male prostitutes, wise women, drummers, priestesses, and priests bloodletting with swords to the accompaniment of music, followed by offerings and sacrifices for the goddess Inanna, or Ninegala. The ceremony reached its climax with the copulation of the king and priestess. | |

| Ishme-Dagan | 1953 BC - 1933 BC | Ishme-Dagan, the fourth ruler of the First Dynasty of Isin succeeded his father Iddin-Dagan during a period of increasing regional instability. His rule marked a shift from the expansions of his predecessor's era toward defensive measures against internal and external threats, as Isin's control over Sumer began to wane amid rivalries with emerging powers like Larsa. Early in his reign, Ishme-Dagan faced significant rebellions in key cities, particularly Isin and Nippur, where local unrest challenged the dynasty's authority. He successfully suppressed these uprisings through military campaigns, restoring order and reaffirming Isin's dominance over its core territories in central Mesopotamia. These efforts were crucial for maintaining loyalty among the priesthood and elites in Nippur, the religious heartland, though they strained resources and highlighted the dynasty's vulnerabilities. A notable cultural response was the composition of the Nippur Lament, which invoked divine favor and legitimated his rule amid the city's distress. To counterbalance these tensions, Ishme-Dagan actively patronised scribes and sponsored elaborate religious festivals, such as those dedicated to the god Enlil, aiming to foster cultural unity and bolster allegiance to the Isin throne. Year names from his reign record generous offerings and temple restorations, which helped legitimise his rule by aligning it with traditional Sumerian piety. This cultural sponsorship was particularly evident in the promotion of literary works and scribal education, reflecting a deliberate strategy to reinforce ideological ties during a time of political flux. Ishme-Dagan's reign also saw escalating conflicts with the rival dynasty of Larsa under King Gungunum, who launched aggressive campaigns against Isin, though major territorial losses occurred later in the dynasty's history. | |

| Lipit-Ishtar | 1934 BC - 1924 BC | Lipit-Ishtar reigned during a period regarded as the zenith of the dynasty's power and influence in southern Mesopotamia. Succeeding his father Ishme-Dagan, who had quelled significant rebellions, Lipit-Ishtar focused on administrative and cultural consolidation, earning titles such as 'king of Sumer and Akkad' and 'pious shepherd of Nippur.' His rule emphasised justice and order, as proclaimed in royal inscriptions that depict him as divinely appointed by Enlil to eradicate enmity and ensure well-being across the land. A hallmark of Lipit-Ishtar's reign was the promulgation of the Code of Lipit-Ishtar, one of the oldest surviving legal compilations from ancient Mesopotamia, inscribed in Sumerian on clay tablets primarily excavated from Nippur's temple library. Lipit-Ishtar's reign also featured ambitious construction efforts, particularly in Nippur, the religious heart of Sumer, where he enhanced the Ekur temple complex dedicated to the god Enlil. As the 'humble shepherd of Nippur,' he undertook projects symbolising his devotion, including repairs and expansions to sacred structures that reinforced Isin's spiritual authority. In Isin itself, he dug a grand moat around the city, as detailed in a reconstructed foundation cone inscription, to protect and glorify his capital while underscoring his role in maintaining regional stability. Under Lipit-Ishtar, the Dynasty of Isin achieved its maximum territorial extent, with suzerainty extending over vital southern cities including Umma, Uruk, Ur, Nippur, and Eridu. However, toward the end of his reign, around 1924 BC, Larsa under Gungunum conquered Ur, marking the beginning of significant territorial losses. This peak influence allowed him to impose corvée labour, a form of unpaid, forced, and intermittent labor imposed by states or landlords on peasants and subjects (e.g., 70 days annually from households) for public works and to liberate dependent regions from subjugation, thereby solidifying Isin's dominance before the dynasty's later challenges. | |

| Ur-Ninurta | 1923 BC - 1896 BC | Ur-Ninurta ushered in a period of intensified military focus amid growing external pressures. His reign represented a departure from the previous rulers' lineage, as ancient king lists do not identify him as Lipit-Ishtar's direct son, suggesting the establishment of a new royal branch. This era inherited the legal and administrative frameworks from Lipit-Ishtar but shifted emphasis toward defensive fortifications. Throughout his rule, Ur-Ninurta faced escalating conflicts with the rival kingdom of Larsa, particularly under its king Sumu-El, involving disputes over water resources and southern Mesopotamian cities. These wars resulted in significant territorial losses for Isin, including the city of Ur, which fell under Larsa control early in his reign, and the temporary seizure of Kisurra by local forces. Ur-Ninurta managed to reconquer Kisurra briefly, but the polity soon emerged as an independent entity under an Amorite tribal leader, Itūr-Šamaš, highlighting the penetration of non-Sumerian elements into the region's political landscape. Signs of mounting instability are evident in contemporary omen literature and chronicles, which include prophetic allusions to royal downfall and divine disfavour amid conflicts, foreshadowing Isin's weakening position. His death, recorded in year names from nearby cities like Babylon and Kisurra, likely occurred in battle against Larsa forces, marking a pivotal moment in the dynasty's transition to decline. | |

| Bur-Suen | 1895 BC - 1874 BC | Bur-Suen's reign occurred during a period of intensifying rivalry with the neighbouring kingdom of Larsa, building on the ongoing conflicts inherited from his predecessor Ur-Ninurta. A prominent feature of Bur-Suen's rule was his emphasis on religious dedications, particularly to Enlil, the chief deity associated with the city of Nippur. In one year-name formula, he is described as 'obedient to Enlil' and credited with crafting emblems of gold and silver for the god, underscoring his efforts to secure divine approval. Bur-Suen undertook restorations at Nippur's Ekur temple complex, the primary sanctuary of Enlil, as evidenced by stamped bricks bearing his dedicatory inscription found in the area. These building efforts, typical of Mesopotamian rulers seeking to legitimise their authority through temple maintenance, reflect a strategic invocation of Enlil's favor to bolster Isin's position. | |

| Lipit-Enlil | 1873 BC - 1869 BC | Reign of Lipit-Enlil Lipit-Enlil, son of Bur-Suen reigned for a period of 5 years marked by escalating pressures from rival states. His rule was characterised by continued rivalry with the kingdom of Larsa, particularly under its king Sumuel, as Isin faced defeats that further undermined its dominance in southern Mesopotamia. Larsa aggressively expanded its influence through conquests and control over vital waterways. In response to these territorial erosions, Lipit-Enlil initiated efforts to fortify Isin itself, strengthening its defences against further incursions, while simultaneously appealing to northern allies—such as powers in Eshnunna and possibly Elam—for military and diplomatic support to counter Larsa's advances. Surviving inscriptions from Lipit-Enlil's era, including year names and dedicatory texts, poignantly lament the contraction of Isin's domain and invoke divine aid amid these crises, reflecting the king's struggle to maintain sovereignty. | |

| Erra-imitti | 1868 BC - 1861 BC | Erra-imitti's reign occurred amid the intensifying rivalry between Isin and Larsa, with the latter under the long rule of Rim-Sin I exerting continued territorial and political pressures on Isin's domains. The most striking episode associated with Erra-imitti's rule is preserved in an Old Babylonian omen text excerpted in the Chronicle of Early Kings. In this account, Erra-imitti, fearing a dire omen portending the king's death — possibly linked to an eclipse or other celestial event — instituted the substitute king ritual by enthroning Enlil-bani, described as his gardener or a lowly cook. The text states: 'Erra-imitti, the king, installed Enlil-bani, the gardener, as substitute king on his throne. He placed the royal tiara on his head. Erra-imitti [died] in the palace while drinking hot broth. Enlil-bani, the substitute king, assumed the throne permanently — he ruled for 24 years.' This narrative, drawn from extispicy (liver divination) traditions, highlights the Mesopotamian practice of using commoners as temporary proxies to absorb predicted misfortunes, thereby protecting the true monarch. Divination texts like this one serve as rare primary sources for Erra-imitti's era, blending factual kingship details with interpretive prophecy to convey moral and astrological lessons. While year names and administrative documents from Isin attest to routine governance under his rule, such as building activities and economic records, the omen anecdote provides the only vivid, if dramatised, insight into a pivotal succession event. Scholars interpret this story as reflecting genuine ritual practices documented across Mesopotamian history, underscoring the precariousness of royal authority amid omens and interstate conflicts. | |

| Enlil-bani | 1860 BC - 1837 BC | Enlil-bani's reign marked a period of relative stability amid the dynasty's decline, characterised by efforts to bolster Isin's religious and administrative infrastructure. Enlil-bani's ascension was unusual, originating from humble beginnings as a gardener (or in some accounts, a cook or tavern-keeper) installed as a substitute king (šar pūḫi) during the reign of his predecessor, Erra-imitti, to avert ill omens such as a predicted eclipse. According to an Old Babylonian omen text preserved in the 'Chronicle of Early Kings', the ritual substitute unexpectedly became the legitimate ruler when Erra-imitti died while eating porridge, allowing Enlil-bani to seize the throne by divine order. This narrative, while possibly legendary, underscores the role of apotropaic rituals (those having the power to avert evil influences or bad luck) in Mesopotamian kingship and highlights Enlil-bani's non-royal background. To rally support and legitimise his rule, Enlil-bani focused on building projects and religious dedications. He restored the city of Nippur, a key religious centre, and constructed or refurbished temples such as the E-me-zi-da for Enki in Eridu; he also dug major canals, including the Enlil-bani canal from the Zuzagum corridor to the sea, enhancing irrigation and economic ties. Votive offerings, like golden thrones for deities including Utu, Nanna, and Ninlil, further emphasised piety toward Enlil and other gods central to Isin's identity. These initiatives provided administrative relief, such as tax exemptions and corvée (indentured labour) releases for Isin's citizens, fostering loyalty during a time of external pressures. Militarily, Enlil-bani achieved minor victories in skirmishes against neighbouring threats, including defensive actions that temporarily secured Isin's borders, though no major conquests are attested in surviving inscriptions. However, his reign saw increasing isolation for Isin as the rival kingdom of Larsa, under expanding rulers like Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin I, dominated southern Mesopotamia through territorial gains and control over key trade routes and water resources. This shift reduced Isin's influence, setting the stage for further dynastic weakening. | |

| Zambiya | 1836 BC - 1834 BC | Zambiya's short reign followed the relative stability achieved under Enlil-bani and was marked by intensified pressures on Isin's territorial control and alliances. During Zambiya's rule, the dynasty experienced accelerated weakening through betrayals by vassals and aggressive encroachments from Larsa. In one notable event around the mid-19th century BC, forces associated with Isin allied with Elamite forces to confront cities like Uruk and Kazallu, aiming to reassert Isin's influence over southern Mesopotamia. However, this coalition proved short-lived, as Larsa's king Sîn-iqīšam claimed victory in his fifth regnal year over 'Uruk, Kazallu, the land of Elam, Zambija the king of Isin', signaling the defection of key allies like Uruk and the direct military subjugation of Isin territories by Larsa. These losses fragmented Isin's vassal network, with former dependents increasingly aligning with Larsa amid the dynasty's declining power. Zambiya sought to uphold the religious prestige of Nippur, the traditional centre of Sumerian cultic authority, by continuing Isin's role as its patron. Inscriptions from his reign, including foundation cones, record dedications and building activities that reinforced Isin's legitimacy as successors to the Ur III dynasty through patronage of Enlil's temple complex. Despite these efforts, the political instability limited their impact. Evidence of economic strain appears in administrative inscriptions and year formulae from Zambiya's era, which highlight resource-intensive projects like the rebuilding of Isin's defensive walls amid ongoing conflicts. One year name commemorates the construction of a wall named 'Zambiya is the beloved of the goddess Ištar', reflecting attempts to bolster fortifications while diverting labour and materials from other needs during a period of territorial contraction. Such endeavours underscore the fiscal pressures faced by the court as Larsa's advances eroded Isin's economic base in the surrounding irrigation-dependent regions. | |

| Iter-pisha | 1833 BC - 1830 BC | Iter-pisha's rule is one of the most poorly attested in the dynasty, with no known royal inscriptions or dedicatory texts attributed to him, reflecting the broader scarcity of records for late Isin kings amid mounting external pressures. The limited surviving evidence consists primarily of administrative documents dated to his regnal years, such as legal tablets from Nippur recording transactions like the sale of priestly offices in temples dedicated to deities including Nininsina and Ningiszida. These texts invoke oaths by the king to validate contracts, indicating ongoing bureaucratic and religious administration under his authority, but they offer no insight into major political or military initiatives. The absence of monumental or historical inscriptions suggests a period of diminished royal activity, possibly focused on defensive maintenance rather than expansion, as Isin faced increasing rivalry from the rising kingdom of Larsa. Iter-pīša's reign likely occurred during a phase of territorial contraction and potential internal challenges, with Larsa under kings like Warad-Sîn exerting pressure, though direct evidence is lacking. This shadowy interlude transitioned to the even more obscure rules of his successors, Ur-dukuga and Sîn-māgir, as Isin's power waned further under Larsite encroachment. | |

| Ur-du-kuga | 1829 BC - 1824 BC | Ur-du-kuga ruled during a period of intensifying decline for the dynasty. His reign coincided with the growing dominance of the rival kingdom of Larsa under Warad-Sîn, which exerted hegemony over much of southern Mesopotamia, including key cities like Ur and Nippur. By this time, Isin's authority was largely nominal, confined to the core area around the city of Isin itself, with administrative tablets from Nippur indicating that Larsa's king was more frequently acknowledged as sovereign. This territorial contraction marked a stark reversal from earlier Isin kings, reflecting the dynasty's struggle to maintain control amid Amorite incursions and regional power shifts. Despite these losses, Ur-du-kuga continued the dynasty's tradition of religious patronage through temple offerings and dedications, emphasising piety as a source of legitimacy. His year names record significant acts such as the fashioning of two large golden emblems for the moon-god Nanna of Ur and the sun-god Utu of Larsa, deities associated with cities under Larsa hegemony, possibly as symbolic assertions of cultural ties or diplomatic gestures. Other dedications included offerings to goddesses like Inanna and Nanaya, as well as the construction of a temple for the god Dagan, underscoring ongoing support for cult centres even as political power waned. These activities align with Isin's historical role as a guardian of Sumerian religious institutions, including the Apsu temple of Enki in Isin, though specific offerings to Enki during his reign are not directly attested in surviving records. Ur-du-kuga's royal ideology represented one of the final expressions of Sumerian traditionalism within the dynasty, adhering to linguistic and stylistic conventions inherited from the Third Dynasty of Ur. Inscriptions and year formulas employed Sumerian language and formats that linked the king to major cult centres like Nippur and Uruk, despite their de facto loss to Larsa, thereby invoking continuity with ancient Sumerian heritage amid encroaching Amorite influences. This focus on religious and cultural continuity, rather than military reconquest, highlighted the 'last gasps' of Isin's Sumerian-oriented worldview as the dynasty approached its end. | |

| Sîn-māgir | 1823 BC - 1813 BC | The primary challenge of Sîn-māgir's rule was the aggressive expansion of Larsa under Rim-Sin I (r. 1822–1763 BC), which led to repeated battles along Isin's southern borders. These conflicts resulted in the loss of key territories, including Uruk and Ur, and culminated in the strategic encirclement of Isin by Larsite forces around 1820 BC, severing vital supply routes and isolating the city-state. In response, Sîn-māgir focused on defensive fortifications, such as the wall at Dunnum built to counter Larsa's advances, as recorded in his royal inscriptions. His year names reflect this strain, including one commemorating the building of a fortress named 'Sîn-māgir-enlarges-the-land', a symbolic assertion of strength amid territorial contraction, and others invoking victories over enemies at Isin's gates, underscoring the kingdom's precarious position. Inscriptions from bricks and votives, such as those dedicating structures to protective deities like Enlil, further highlight these futile efforts to bolster defences and legitimacy. | |

| Damiq-ilishu | 1812 BC - 1790 BC | The rule of Damiq-ilīšu, son of Sîn-māgir, occurred amid intensifying rivalries between Isin and the rising power of Larsa under Rim-Sin I, compounded by pressures from Babylon. Administrative records and inscriptions from his early years document efforts to bolster defences, including the fortification of the city of Dunnum with a wall named 'Sîn-māgir makes the foundations of his land firm.' By the mid-point of his reign, Isin faced significant military setbacks. In circa 1796 BC, corresponding to the seventeenth year of Sîn-muballiṭ of Babylon, Isin suffered an assault that further eroded its territorial control. This vulnerability culminated in Rim-Sin I's decisive campaigns against Isin. In his twenty-ninth regnal year (circa 1794 BC), Rim-Sin captured Dunnum, seizing its fortifications and prisoners, which critically weakened Isin's northern defenses. The following year, Rim-Sin's thirtieth year (c. 1793 BC), marked the fall of Isin itself, ending the First Dynasty. The conquest is commemorated in Rim-Sin's year name: 'Year in which the true shepherd Rīm-Sîn, with the mighty aid of An, Enlil, and Enki, seized Isin, the royal city, together with its numerous settlements; he spared the lives of its vast population and perpetuated the glory of its kingship forever.' Following the conquest, Larsa annexed Isin's territories, integrating them into its domain and shifting administrative control, including over key religious centers like Nippur.[40] Year-name records from Rim-Sin's subsequent reigns employed an era system counting "after the seizure of Isin," underscoring the event's significance and the permanence of Larsa's dominance.[40] (Sigrist 1990: 61–90). The fate of Damiq-ilīšu and his royal family remains sparsely documented in primary sources, with evidence suggesting absorption into Larsa's administrative or cultic structures rather than outright exile; indirect attestations include Isin royal women continuing roles in priesthoods at Ur.[40] Some later traditions hint at shadowy continuations of Isin lineage, as seen in claims by rulers of the remote Sealand Dynasty, but these lack direct corroboration from contemporary inscriptions. Damiq-ilīšu was the 15th and final king of Isin. | |

| Dynasty of Larsa | |||

| Naplanum | 2025 BC - 2004 BC | Naplanum was the founder of the ruling dynasty of Larsa. He may not originally have been a king but possibly a local official or governor. During the weakening of Ur III authority, he established independent control over Larsa. His background was likely Amorite, reflecting the growing influence of Amorite groups in Mesopotamia at the time. | |

| Emisum | 2004 BC - 1997 BC | Emisum or Iemsium governed the city of Larsa. He was an Amorite. Historical records about him are limited, but he appears in Sumerian king lists and year-name inscriptions. His reign occurred during a time of political fragmentation after the decline of the Third Dynasty of Ur. | |

| Samium | 1976 BC - 1942 BC | Samium (also written Samuʾum) reigned during a time of political rivalry among Mesopotamian city-states after the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Samium was likely an Amorite ruler, part of the growing Amorite influence in Mesopotamia. His reign helped consolidate the authority of Larsa as an independent kingdom. Samium continued Larsa’s resistance to Isin’s claims of supremacy. | |

| Zabaia | 1941 BC - 1933 BC | Zabaia was the son of Samium, and the first to call himself 'king'. Isin had initially claimed supremacy over southern Mesopotamia, but Larsa was steadily strengthening. Zabaia’s reign represents the period just before Larsa began a major territorial expansion. He honoured the sun god Shamash, the chief deity of Larsa. Zabaia’s reign appears to have been relatively stable and served as a bridge between early consolidation and later expansion. | |

| Gungunum | 1932 BC - 1906 BC | Gungunum was a powerful king of Larsa whose reign marked the beginning of Larsa’s major rise to regional power. By the time he came to the throne, Larsa was already independent but not yet dominant. He transformed Larsa from a secondary power into a major political force. Gungunum is best known for his military successes, especially against Isin. His major achievement was the capture of Ur, , one of the most important religious and economic centres in Mesopotamia in 1924 BC. Control of Ur gave Larsa access to major trade routes and religious prestige. He also extended influence over parts of southern Sumer and possibly areas toward Elam. He honoured the moon god Nanna (chief deity of Ur) after conquering the city. His control of Ur strengthened his legitimacy as a ruler of Sumerian lands. By controlling Ur, Gungunum gained access to Gulf trade routes. The resulting increased wealth strengthened Larsa’s economy. | |

| Abisare | 1905 BC - 1895 BC | Abisare continued Larsa’s expansion and consolidation of power, and inherited a strengthened and expanding kingdom. He continued the conflict with Isin, and reportedly defeated Isin in battle, further weakening its political power. Abisare honoured important deities, especially the moon god Nanna of Ur and the sun god Shamash of Larsa. Religious devotion was closely tied to royal legitimacy. He maintained irrigation systems essential for agriculture and preserved control over trade routes gained during previous reigns. | |

| Sumu-ilu | 1894 BC - 1866 BC | Sumu-ilu's reign marked a phase of continued military pressure and territorial consolidation following the expansion under earlier kings like Gungunum and Abisare. (also written Sumuel) Sumu-ilu (also written Sumuel) inherited a strong and expanding kingdom. Larsa was already a major power in southern Mesopotamia, rivaling Isin. Sumu-ilu continued the conflict with Isin, and reportedly captured several cities previously controlled by Isin. He built defensive walls around strategic cities to secure his gains. Although he did not completely destroy Isin, he significantly weakened it. During his reign, Larsa strengthened control over Ur and Uruk. These cities were religious and economic centres, making Larsa one of the dominant powers in Sumer. Sumu-ilu supported the cult of Shamash (sun god of Larsa) and maintained the cult of Nanna in Ur. He maintained irrigation systems essential for agriculture and protected trade routes connected to the Persian Gulf. He strengthened city defences through construction projects, and his reign was characterised by administrative stability. His reign marked a high point of Larsa’s territorial consolidation. | |

| Nur-Adad | 1865 BC - 1850 BC | Nur-Adad's reign marked a shift from aggressive expansion to internal consolidation and religious rebuilding. He inherited a powerful kingdom controlling major southern cities such as Ur and Uruk. Larsa was one of the dominant powers in southern Mesopotamia at this time. Conflict with Isin continued, though less aggressively than under Sumu-ilu. Nur-Adad focused more on maintaining territories rather than expanding them dramatically. He worked to stabilise Larsa after decades of warfare. Nur-Adad is especially known for his construction and restoration activities. He rebuilt temples in Larsa and possibly in Ur, strengthened city walls, supported the cult of Shamash (sun god of Larsa) and continued honouring Nanna, the moon god of Ur. In Mesopotamian kingship, temple restoration was both a religious duty and a political statement of legitimacy. He maintained irrigation canals and agricultural systems, preserved trade routes linking southern Mesopotamia to the Persian Gulf and ensured administrative continuity after earlier military campaigns. | |

| Sin-iddinam | 1849 BC - 1843 BC | Sin-iddinam was the son and successor of Nur-Adad and continued efforts to maintain Larsa’s power in southern Mesopotamia. He inherited a strong but politically pressured kingdom. Larsa controlled major southern cities, still including: Ur and Uruk. However, rival powers were rising in the region. Conflict with Isin continued. New regional powers, including Babylon, were beginning to gain strength. Sin-iddinam worked to defend Larsa’s territories and maintain influence. Although not as expansionist as earlier rulers, he aimed to preserve Larsa’s dominance. Sin-iddinam is known from inscriptions that highlight restoration and dedication of temples, support of Shamash (sun god of Larsa) and continued patronage of Nanna (moon god of Ur). His reign appears relatively stable but short. | |

| Sin-iribam | 1842 BC - 1841 BC | Sin-iribam's short reign suggests possible internal political instability or dynastic tension. Larsa at this time was still a major power but facing increasing regional challenges. Rivalries with Isin continued, though Isin’s power had declined. Other regional states, including Babylon, were rising. Larsa may have been experiencing internal political strain during this time. Due to the brevity of his rule, no major military conquests are clearly recorded. | |

| Sin-iqisham | 1840 BC - 1836 BC | Sin-iqisham continued military pressure against neighbouring cities, strengthened defensive walls and irrigation systems and maintained control over major southern cities such as Ur and Uruk.His reign was more stable than that of his predecessor. | |

| Silli-Adad | 1835 BC | Silli-Adad's reign was very short and is often seen as part of a period of political instability. He may not have belonged to the main ruling line of Nur-Adad’s family. His short rule suggests either internal conflict or external pressure. Very few inscriptions survive from his reign. He was soon replaced by a stronger ruler, Warad-Sin, who restored dynastic stability. | |

| Warad-Sin | 1834 BC - 1823 BC | Warad-Sin was a major stabilising figure in Larsa’s history. He was the brother of Rim-Sin I and the son of Kudur-Mabuk, an influential Amorite leader. Warad-Sin came to power after the unstable reign of Silli-Adad. His father, Kudur-Mabuk, an Amorite ruler from the region near Elam, likely played a decisive role in securing the throne. This marked the beginning of a new and powerful ruling house in Larsa. Warad-Sin worked to consolidate control over southern Mesopotamia. He maintained authority over Ur and Uruk, and engaged in regional conflicts to preserve Larsa’s dominance. He is well known for temple restorations in Ur and Larsa and his devotion to the moon god Nanna (Ur) and the sun god Shamash (Larsa). His inscriptions show strong emphasis on divine support for his rule. | |

| Rim-Sin I | 1822 BC - 1763 BC | Rim-Sin I was the most powerful and longest-reigning kings of Larsa. Under his rule, Larsa reached its political and economic peak during the Isin–Larsa period of Mesopotamian history. He was the brother of Warad-Sin and son of Kudur-Mabuk. He inherited a stable and expanding kingdom. His greatest victory was the final defeat of Isin. Around 1794 BCE, Rim-Sin captured Isin after more than a century of rivalry between Isin and Larsa. This event ended the long Isin–Larsa conflict and made Larsa the dominant power in southern Mesopotamia, which greatly increased his prestige. At its height under Rim-Sin I, Larsa controlled major cities including , Ur, Uruk and Lagash, as well as Nippur (at times). He became the most powerful ruler in southern Mesopotamia. Rim-Sin I restored major temples in Ur and Larsa, honoured Nanna (moon god of Ur) and Shamash (sun god of Larsa), built canals and improved irrigation systems. He used year names to celebrate achievements, especially the conquest of Isin. Temple building reinforced his legitimacy as ruler of Sumer. He controlled important agricultural lands, managed trade routes connected to the Persian Gulf, maintained large irrigation networks and strengthened administrative systems. Larsa became wealthy and stable during much of his reign. During Rim-Sin’s reign, a new power, Babylon, ruled by Hammurabi was rising in the north. At first, Rim-Sin was stronger than Babylon. However Hammurabi gradually expanded his kingdom. In 1763 BCE, Hammurabi defeated Rim-Sin and captured Larsa. Rim-Sin was deposed, and Larsa was incorporated into the Babylonian kingdom. This marked the end of Larsa as an independent power. Rim-Sin I is important because he ruled for about 60 years — one of the longest reigns in Mesopotamian history. He ended the Isin–Larsa rivalry and made Larsa the dominant southern power. His defeat by Hammurabi paved the way for Babylonian unification of Mesopotamia. | |

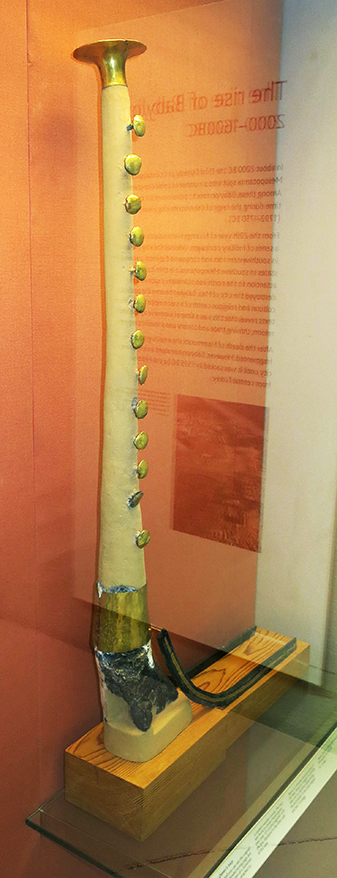

| Dynasty I (Amorite, 1894–1595 BC): Founded by Sumu-abum, famous for Hammurabi. Dynasty II (First Sealand, c. 1725–1475 BC. Based in the southern marshlands.) Dynasty III (Kassite, c. 1595–1155 BC): Longest-ruling dynasty, establishing lasting Babylonian culture. Dynasty IV (Second Isin, 1153–1022 BC): Native Babylonian rulers after the Kassite fall. Dynasty V (Second Sealand, 1021–1001 BC): Short-lived dynasty. Dynasty VI (Bazi, 1000–981 BC): Named after a town on the Tigris. Dynasty VII (Elamite, 980–975 BC): A brief period of foreign rule. Dynasty VIII (E, 974–732 BC): A period of instability, sometimes called "Intermediate Period". Dynasty IX (Assyrian, 732–626 BC): Ruled directly by the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Dynasty X (Chaldean/Neo-Babylonian, 626–539 BC): Founded by Nabopolassar, including Nebuchadnezzar II. Naming Conventions Geographic/Ethnic Origin: Dynasties were often identified by the regional background of their leaders, such as the Kassites or Chaldeans. City of Origin: Some, like the Second Dynasty of Isin, were named after the city from which the kings originated. King Lists: Modern scholars and ancient scribes used sequential numbers (I-X) to organize the dynasties. Reign Identification: Within these periods, years were not numbered consecutively but were named after major events during a king's reign. |

|||

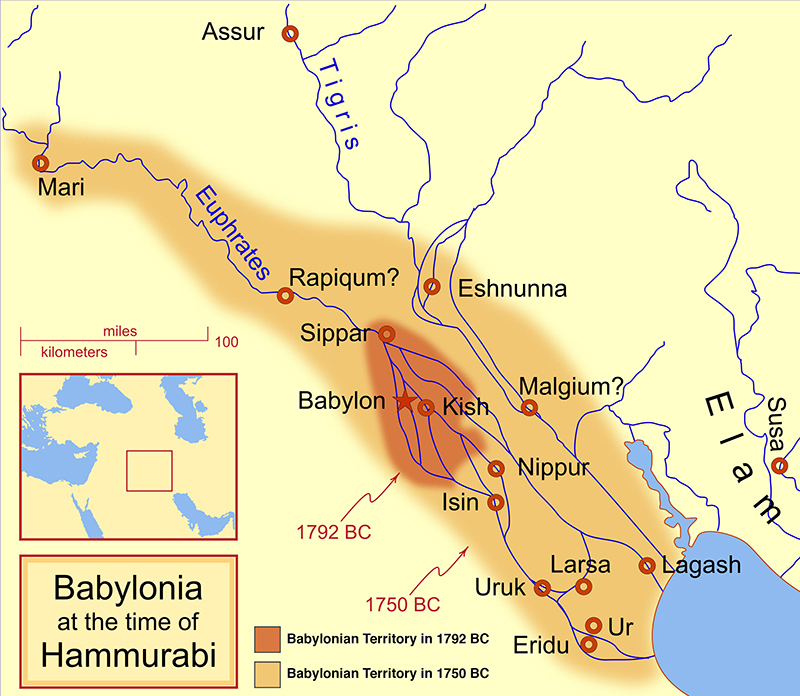

| Sumu-abum | 1894 BC - 1881 BC | The Old Babylonian Dynasty (circa 1894 BC – 1595 BC) marked the rise of Babylon from a small city-state to a dominant Mesopotamian power. The founder of the dynasty was Sumu-abum who established Babylon as an independent city-state after the decline of the Ur III Empire. He consolidated control over nearby cities and laid the political foundation for Babylon’s future expansion. He did not yet control a vast empire, but he began the Amorite dynasty that would eventually dominate southern Mesopotamia. | |

| Sumu-la-El | 1880 BC - 1845 BC | Sumu-la-El was an early consolidator who strengthened Babylon’s defences with city walls. He expanded territory by conquering nearby rival cities and improved irrigation systems and temple construction. Under his rule, Babylon became a more significant regional power. | |

| Sabium | 1844 BC - 1831 BC | Sabium continued territorial expansion. He reinforced political control over surrounding cities and maintained stability during a competitive period among Mesopotamian city-states. | |

| Apil-Sin | 1830 BC - 1813 BC | Apil-Sin strengthened city fortifications. and engaged in regional conflicts, particularly with neighbouring city-states such as Isin and Larsa, and helped prepare the kingdom for later expansion. | |

| Sin-Muballit | 1812 BC - 1793 BC | Sin-Muballit expanded Babylon’s territory further and launched campaigns against rival cities including Larsa. His reign set the stage for Babylon’s greatest expansion. He abdicated in favour of his son, Hammurabi (possibly due to illness). | |

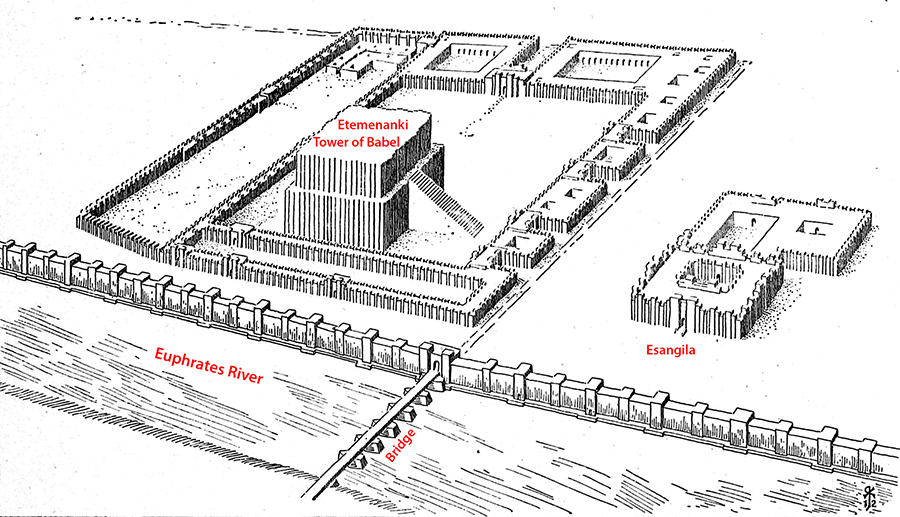

| Hammurabi | 1792 BC - 1750 BC | Hammurabi was the most famous ruler of the dynasty. He conquered major Mesopotamian cities including Larsa, Eshnunna, Mari, and eventually Assyria. He united much of Mesopotamia under Babylonian rule. He issued the Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest and most complete written legal codes up till that point. He promoted large scale irrigation projects and temple construction. Under Hammurabi, Babylon became the dominant political and cultural centre of Mesopotamia. | |

| Samsu-iluna | 1749 BC - 1712 BC | Samsu-iluna faced widespread revolts after Hammurabi’s death. He struggled to maintain control over southern Mesopotamia and lost significant territories, weakening Babylon’s dominance. His reign marked the beginning of the empire’s gradual decline. | |

| Abi-Eshuh | 1711 BC - 1684 BC | Abi-Eshuh attempted to suppress rebellions and recover lost territories. and built defensive works and attempted to control the Tigris River to undermine enemies but he had limited success restoring Babylon to its former strength. He was defeated by Damqi-ilishu of the Babylonian Dynasty II, the Sealanders, from the marshes south of Babylon. | |

| Ammi-Ditana | 1683 BC - 1647 BC | Ammi-Ditana presided over a period of relative stability, and focused on religious dedications and temple restorations, as well as promoting economic and administrative continuity. | |

| Ammi-Saduqa | 1646 BC - 1626 BC | Ammi-Saduqa issued decrees aimed at economic justice and debt relief, and continued religious and administrative traditions. But he was best known for the 'Venus Tablets', which were astronomical observations of Venus. The Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa (part of the Enuma Anu Enlil series) is a crucial 17th-century BC Babylonian cuneiform text recording 21 years of observations of Venus's rising and setting (heliacal risings/settings). It is one of the oldest known astronomical texts, used to date Mesopotamian chronology. It records the first and last visibility of Venus, defining its synodic period. The synodic period of Venus is the time it takes for Venus to return to the same position relative to the Sun as seen from Earth. It is approximately 584 days (or roughly 1.6 years). This cycle, known as the Venusian synodic cycle, includes periods as both a morning and evening star and is characterised by a 5:8 ratio with the Earth's orbit, completing a full cycle of positions every 8 years. Besides tracking Venus, the tablet also contains omens linking celestial movements to floods, food availability, and war outcomes. These tablets demonstrate that Babylonian astronomers accurately tracked planetary motion, with some researchers suggesting they even recorded the atmospheric effects of the Thera (Santorini) volcanic eruption. The tablets were found in the library of Nineveh (Kouyunjik) and are now housed in the British Museum and the Iraqi Museum. | |

| Samsu-Ditana | 1625 BC - 1595 BC | Samsu-Ditana was the last ruler of the dynasty. He reigned during a period of significant weakness. Babylon was sacked around 1595 BC by the Hittite king Mursili I. The fall of Babylon ended the Old Babylonian Dynasty. After this event, the Kassites eventually rose to power in Babylon. | |

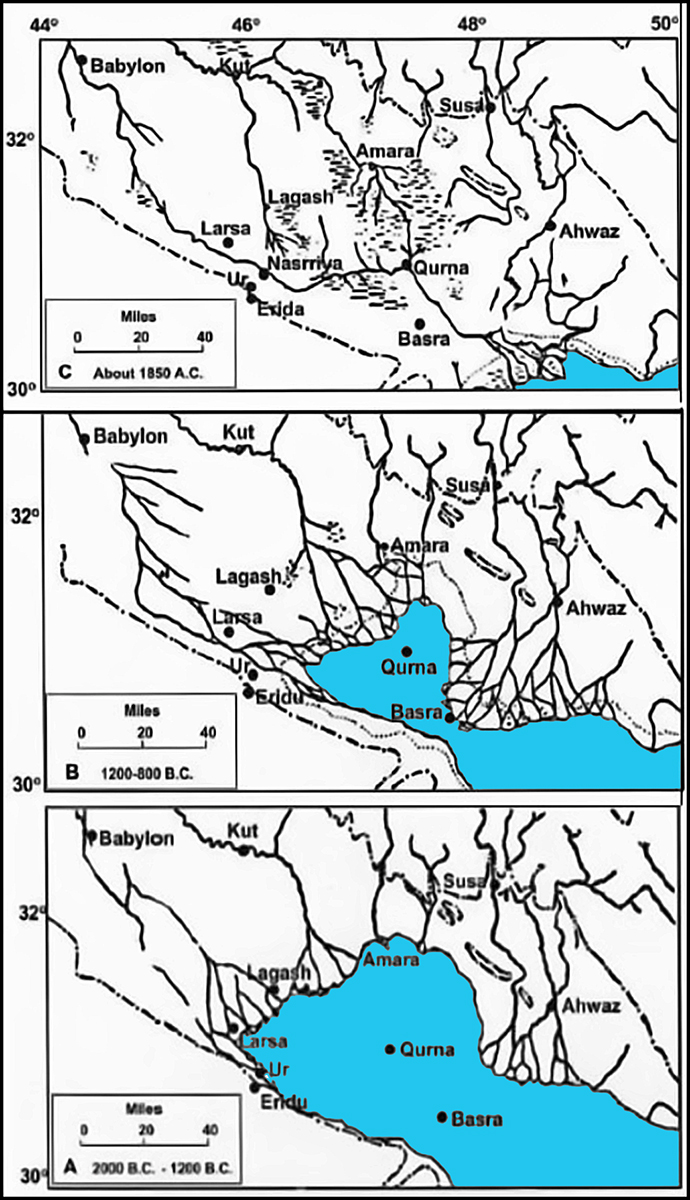

| First Sealand Dynasty, circa 1732–1475 BC. Based in the southern marshlands. The dynasty, which had broken free of the Old Babylonian Empire, was named for the province in the far south of Mesopotamia, a swampy region bereft of large settlements which gradually expanded southwards with the silting up of the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (the region known as mat Kaldi 'Chaldaea' in the Iron Age). Sealand pottery has been found at Girsu, Uruk, and Lagash but in no site north of that. |

|||

| Ilum-ma-ili | 1732 BC - 1725 BC | Ilum-ma-ili was born in the Sealand region of southern Mesopotamia, and he founded the First Sealand dynasty after rebelling against the Amorite rulers of Babylon in 1732 BC. Ilum-ma-ili battled the Amorite kings Samsu-iluna and Abi-Eshuh, he conquered Nippur and used the terrain to counter Abi-Eshuh's efforts to dam the Tigris and flush Ilum-ma-ili and his Sealanders out of their homeland. He died in 1725 BC and was succeeded by his son Itti-ili-nibi. | |

| Itti-ili-nibi | circa 1700 BC | Itti-ili-nibi was a king of the First Sealand Dynasty in the region south of Babylon. He is considered the second ruler of this dynasty, succeeding the founder, Ilum-ma-ili. The Sealand Dynasty was characterised by its efforts to maintain independence in southern Mesopotamia against the Amorite rulers of Babylon (such as Abi-Eshuh). He ruled during a period of instability following the decline of the First Babylonian Dynasty (Amorite dynasty). He was succeeded by Damqi-ilishu. He was a contemporary of King Bel-bani of Assyria and Pharaoh Merdjefare in Egypt. | |

| Damqi-ilishu | circa 1677 BC | Damqi-ilishu or Damqi-ilishu II likely ruled for 26 years, during a period when the Sealand Dynasty overlapped with the First Dynasty of Babylon. The Sealand Dynasty was a contemporaneous, independent dynasty, not a successor to the Old Babylonian (Amorite) Dynasty in the city of Babylon itself. He is noted for defeating Abi-Eshuh, a successor to Samsu-iluna of the First Dynasty of Babylon, in an attempt to control the region.

It is important not to confuse him with the 15th and final king of the Kingdom of Isin, named Damiq-ilishu, who died around 1792 BC |

|

| Iškibal | circa 1650 BC | There are no known monumental inscriptions or detailed royal narratives about his reign. Like other Sealand kings, he probably ruled from a marshland capital (possibly Dur-Enlil or another southern city), nanaged trade routes linking Mesopotamia with the Persian Gulf and maintained regional autonomy during a politically unstable period. Iškibal is typically credited with a reign of approximately 15 years. He was succeeded by his brother Shushi. | |

| Shushi | 1625 BC - 1602 BC | Shushi was the fifth king of the Sealand dynasty. He is known only from later king lists. According to these lists, he reigned for 24 years. The name Shushi is problematic but is possibly Akkadian. According to the Babylonian King List, Šušši was the brother of Iškibal. Šušši is recorded as reigning for 24 years. | |

| Gulkishar | 1602 BC - 1563 BC | Gulkishar was the sixth king from the First Sealand dynasty. He reigned over a part of Lower Mesopotamia around 1595 BCE, contemporarily with the end of the reign of Samsu-Ditana, the final ruler from the First Dynasty of Babylon. The full territorial extent of his kingdom remains uncertain, though it is assumed that it encompassed the shore of the Persian Gulf, the lower Tigris and Euphrates, as well as part of central Babylonia. It remains a subject of debate among researchers whether he ever controlled Babylon itself. In contrast with many other members of his dynasty, who are only known from king lists, he continued to be referenced in various genres of texts up to the first millennium BCE. The best-known example is an epic portraying his conflict with Samsu-Ditana, in which he is aided by the goddess Ishtar. It can be established that he must have already been in power circa 1595 BC. According to the Babylonian King List A his reign lasted 55 years. However, it is possible that this source slightly exaggerates the lengths of reigns of the individual kings of the Sealand. It has been suggested that its compilers rounded them up to numbers ending in 0 or 5 when no detailed records were available to them, though this remains speculative. Gulkishar has been characterised by Assyriologists as an ambitious ruler. During his reign the Sealand state consolidated power across Mesopotamia in the aftermath of the sack of Babylon by Mursili I and his Hittite forces. The full extent of the kingdom of Sealand remains uncertain, though it can be assumed that it encompassed the lower Tigris and Euphrates, and that it reached up to the shore of the Persian Gulf in the south[e] and possibly up to central Babylonia in the north. It is uncertain if Nippur was a part of it, despite the importance of deities associated with it in the official pantheon. | |

| Peshgaldaramesh | 1599 BC - 1549 BC | Peshgaldaramesh reigned for approximately 50 years. He was the son of Gulkishar, who was a significant ruler of the First Sealand Dynasty, having reigned for 55 years. Peshgaldaramesh is one of the better-attested kings in the later part of this dynasty, which, despite the lack of extensive, detailed records, is documented in the King List. He was followed by his son, Ayadaragalama, who reigned from 1548 BC to 1520 BC. | |

| Ayadaragalama | 1548 BC - 1520 BC | Ayadaragalama refers to an ancient Mesopotamian king — not a festival or event with modern dates. Here’s a concise overview of who he was and his historical significance: Ayadaragalama is recorded as one of the better-documented rulers of this dynasty through cuneiform texts. This places him in the Middle Bronze Age period of Mesopotamian history. In ancient Mesopotamia, years were often named after major events; around fourteen such year names are associated with his reign, with mentions of religious acts and conflicts. Some year-names mention repelling enemies and building defensive works, likely against Kassite and Elamite groups. Texts note offerings and rituals to gods like Enlil and Ea. Texts and Archives: Many of the surviving texts with his name come from cuneiform archives (e.g., the Schøyen Collection). Scholars have examined a hymn attributed to Ayadaragalama, which praises the gods of Nippur and provides cultural and religious context for his reign. He was known for expanding his control into central Babylonia. | |

| Akurduana | 1519 BC - 1493 BC | Akurduana (c. 1519–1493 BC). Akurduana ruled the region south of Babylon during a period of overlap with the Old Babylonian and Kassite periods. Known from the Synchronistic Kinglist, he was a contemporary of Assyrian King Puzur-Ashur III and Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose I. He ruled for approximately 26 years as part of the Sealand Dynasty. His reign occurred after the fall of the First Babylonian Dynasty to the Hittites, during a time when the Sealand kings held power in southern Mesopotamia. | |

| Melamkurkurra | 1492 BC - 1485 BC | Melamkurkurra reigned for approximately 7 years, he succeeded Akurduana and was followed by Ea-gamil, who may have been his son. His reign occurred during a period of complex, shifting power dynamics in the region. Key Details About Melamkurkurra: Timeline: c. 1492–1485 BC or 1491–1484 BC. He ruled the southern region of Mesopotamia (the 'Sealand') rather than Babylon itself, while the region experienced turmoil and the end of the Amorite dynasty. Succession: Succeeded by Ea-gamil, hia son, the final king of the dynasty | |

| Ea-gamil | 1484 BC - 1475 BC | Ea-gamil, the last king of the dynasty and was the son of Melamkurkurra. He ruled briefly before fleeing to Elam following an invasion by the Kassite king Ulam-Buriash, brother of the Babylonian king Kashtiliash III. Ulam-Buriash conquered the Sealand which ended the dynasty and allowed the Kassites to take control of the region. Rather than facing defeat, Ea-gamil fled to Elam. He had a distinctly Sumerian name. | |

Note that there are significant gaps in the kings list, and there is significant doubt about the dates given for all members of this dynasty. |

|||

| Gandash | 1595 BC - 1594? BC | The Kassite Dynasty ruled Babylon for over 500 years, with 36 kings traditionally listed. They brought long-term stability and adopted Babylonian culture, while early kings like Gandash and Agum II established their rule, and later kings like Kurigalzu I/II and Burnaburiash II engaged in international diplomacy. Gandash (circa 16th century BC) is traditionally considered the founder of Kassite rule in Babylon. He may not have ruled all of Babylonia, but he established the Kassite political presence. Little direct evidence survives. | |

| Agum II | 1594 BC - 1573 BC | Agum II is identified as one of the early kings of the Kassite Dynasty, which took control of Babylon after it was sacked by the Hittite king Mursilis I in 1595 BC (middle chronology). According to tradition (specifically the 'Agum-kakrime Inscription'), he is noted for recovering the statue of the god Marduk that had been stolen by the Hittites, suggesting a reign roughly 24 years after the statue was originally taken. He is considered the king who firmly established the Kassite Dynasty in Babylon. | |

| Burnaburiash I | 1570 BC - 1550 BC | Burnaburiash I strengthened Kassite control over Babylonia following the dynasty’s rise after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire. He helped stabilise political authority during the early Kassite period. He secured the Kassite royal line and passed the throne to his successor, likely his son Kashtiliash III (according to king lists, though early Kassite succession is somewhat uncertain). He continued traditional Babylonian religious practices and supported major temples, especially in Babylon, reinforcing legitimacy by honouring Babylonian deities. | |

| Kashtiliash III | 1550 BC - 1530 BC | Kashtiliash III is generally placed immediately after Burnaburiash I in the early Kassite dynasty (mid-16th century BCE, though the exact dates are uncertain). As with much of early Kassite history, the sequence comes from later king lists and is not perfectly secure, but Kashtiliash III is the standard successor in modern reconstructions. | |

| Ulamburiash | 1530 BC - 1500 BC | Ulamburiash was a Kassite king who expanded Kassite control, particularly into the Sealand region of southern Mesopotamia. He is considered one of the early rulers who helped consolidate Kassite authority over Babylonia. | |

| Agum III | 1465 BC - 1436 BC | Agum III, son of Kaštiliyåš, appears to have been one of the successors to Burna-Buriyåš I, because he is mentioned in the Chronicle of Early Kings after Ulam-Buriyåš, who was a son of Burnaburiash I. Although this source does not give him a royal title, it is inconsistent in this regard and does say he called up his own army, ummānšu idkēma. Little is known about the king, with the only Babylonian reference to him from an expedition he led against 'the Sealand', a region synonymous with Sumer, ca. 1465 BC, which is described in the Chronicle of Early Kings. His invasion followed that of his uncle, Ulam-Buriyåš, described in the preceding lines of the chronicle, who had previously made himself 'master of the land', i.e. Sealand. Whether the campaign was against a competing Kassite kingdom, a restive province or a resurgent Sealand dynasty is not disclosed. He reputedly conquered the city of Dur-Enlil which is otherwise unknown and destroyed its temple of Egalgašešna, leaving him in control of all of southern Mesopotamia. | |

| Kadashman-Sah | 1435 BC - 1415 BC | King of Babylon from 1435 to 1415 BC, succeeding Agum III and preceding Karaindash. | |

| Karaindash | 1415 BC - 1400 BC | Karaindash built temples in Uruk, established diplomatic relations with Egypt, and promoted architectural development. | |

| Kadashman-Harbe I | 1400 BC - 1387 BC | Kadashman-Harbe I was a King of Babylon during the Kassite dynasty who reigned in the early 14th century BC, specifically cited as ruling from roughly 1400 to 1387 BC. He was the son of Karaindash, campaigned against the Suteans, and is recognised as a contemporary of the Elamite king Tepti Ahar. He was the 16th King of the Kassite (3rd) Dynasty of Babylon. He campaigned against the Suteans near the Euphrates. Contemporary Rulers were Tepti Ahar of Elam and Amenhotep II of Egypt. | |

| Kurigalzu I | 1386 BC - 1375 BC | Kurigalzu I founded a new capital city, Dur-Kurigalzu (near modern Baghdad). He constructed monumental temples and a large ziggurat. He strengthened royal authority. | |

| Kadashman-Enlil I | 1374 BC - 1360 BC | Kadashman-Enlil I is known to have been a contemporary of Amenhotep III of Egypt, with whom he corresponded (Amarna letters). This places him securely to the first half of the 14th century BC by most standard chronologies. Kadashman-Enlil I was one of the most prominent Kassite kings of Babylon during the Late Bronze Age international era. His reign fell during a time when Babylonia was part of a network of powerful states that included Egypt, Mitanni, the Hittites, and Assyria. | |

| Burnaburiash II | 1359 BC - 1333 BC | Burnaburiash II engaged in extensive diplomatic correspondence with Egypt (recorded in the Amarna Letters). He maintained international relations with major powers including Egypt, Mitanni, and the Hittites and oversaw a period of prosperity and trade. | |

| Kurigalzu II | 1332 BC - 1308 BC | Kurigalzu II made war with Assyria. He maintained Kassite authority in Babylonia despite growing Assyrian power. | |

| Nazi-Maruttaš | 1307 BC - 1282 BC | Nazi-Maruttaš was the 23rd king of the dynasty, succeeding his father, Kurigalzu II. He ruled during the Middle Babylonian period and is known for his role as a 'King of the World'. His reign is associated with the Nazimaruttaš kudurru stone, a boundary stone now in the Louvre Museum. He appears in literary texts that were copied well after his reign, indicating a significant historical footprint compared to other Kassite rulers. | |

| Kadašman-Turgu | 1281 BC - 1264 BC | Kadašman-Turgu was the 24th king of the Kassite Dynasty or 3rd dynasty of Babylon. He succeeded his father, Nazi-Maruttaš, continuing the tradition of proclaiming himself 'king of the world' and went on to reign for eighteen years. He was a contemporary of the Hittite king Ḫattušili III, with whom he concluded a formal treaty of friendship and mutual assistance, and also Ramesses II with whom he consequently severed diplomatic relations. Kadašman-Turgu reigned during momentous times, but seems to have played only a peripheral role. Ḫattušili III, in a letter to his son and successor Kadašman-Enlil II, said of him, 'they used to call [your father] a king who prepares for war but then stays at home'. His personal seal included suckling animals in two registers, allegorically symbolising his care for his subjects. The continued employment of the extinct Sumerian language in royal votive inscriptions was in decline and the Babylonian calendar was under revision with the introduction of the Akkadian term: Šanat rēš šarrūti, 'accession year'. Early in his reign, he brokered a treaty with the Assyrian king Adad-Nīrāri. Kadašman-Turgu’s father, Nazi-Maruttaš had been engaged in a protracted war with both Adad-Nīrāri and his father Arik-den-ili which had reached its dénouement in a battle at Kār-Ištar of Ugarsallu. This settlement perhaps explains why there were no reports of any conflict between the Babylonians and Assyrians during this time. It also freed the Assyrians to turn their attention to conquering their westerly neighbour and former overlord the Mitanni. | |