Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

El Castillo Cave

El Castillo Cave entrance, Spain

Photo: Edward the Confessor

Date: April 2008

Permission: GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version

The Cueva de El Castillo, or the Cave of the Castle, is an archaeological site within the complex of the Caves of Monte Castillo, and is located in Puente Viesgo, in the province of Cantabria, Spain. This cave was discovered in 1903 by Hermilio Alcalde del Río, the Spanish archaeologist, who was one of the pioneers in the study of the earliest cave paintings of Cantabria. In the time of the cave painters, the entrance to the cave was not as large as it is today, because it was enlarged by the excavations in the front of the caves. By way of the entrance one can access the different rooms in which Alcalde del Río found an extensive sequence of images. The paintings and other markings span from the Lower Palaeolithic to the Bronze Age, and even into the Middle Ages. There are over 150 figures already catalogued, including engravings of deer, complete with shadowing.

Text above adapted from Wikipedia

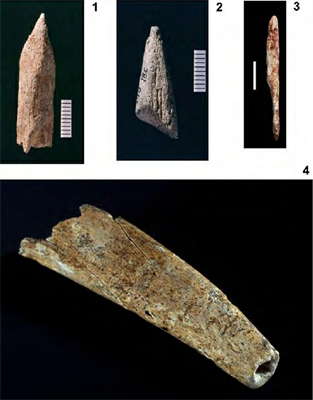

Perforated baton from the Upper Magdalenian of El Castillo Cave. It has been decorated with an engraving of a deer.

It has been dated to between 13 300 and 11 500 BP. It measures about 20 cm and is made of deer antler. It was found at the beginning of the 20th century by Hugo Obermaier.

Photo: Ángel M. Felicísimo from Mérida, España

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Source and text: Wikipedia

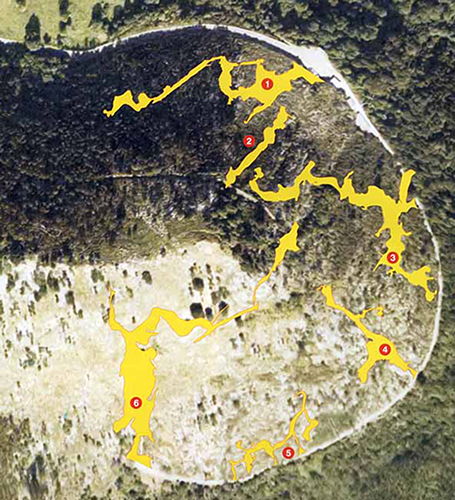

Very close to the town of Puente Viesgo (Cantabria) is Monte Castillo, where a set of caves with cave art of exceptional value is located. These are the caves of:

1 El Castillo (the castle)

2 El Lago (the lake)

3 Las Chimeneas (the chimneys)

4 La Flecha (the arrow)

5 La Pasiega (a highlander of Santander)

6 Las Monedas (the coins)

Photo: http://apuntes.santanderlasalle.es/arte/prehistoria/franco_%20cantabrica/puente_viesgo.htm

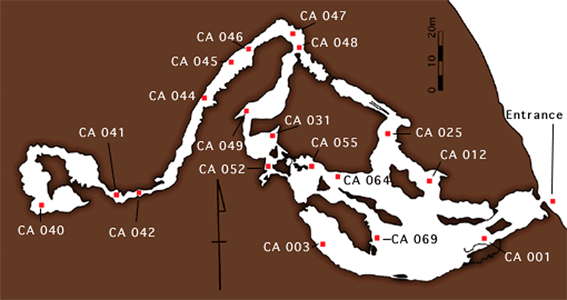

Plan of El Castillo Cave.

This cave takes its name from the hill where it is situated, overlooking the town of Puente Viesgo, in the center of Cantabria. In 1903, an important archaeological deposit was located in the entrance vestibule of the cave, and numerous paintings and engravings were discovered in its interior. Hermilio Alcalde del Río, a local teacher, was the discoverer, and he also undertook the first studies in the site. Later, at different times during the century, other caves were found in the same hill, whose entrances had been blocked and hidden by collapses. These are the caves, each with an archaeological deposit and cave art, of La Pasiega, Las Chimeneas and Las Monedas; as well as La Flecha, which only had an archaeological deposit in its entrance.

In the Upper Paleolithic, the large outer rock-shelter at El Castillo, 190m above sea level and facing east-northeast, was occupied much more often than the other caves which were then open. It was thus the main habitat in the hill and in all the immediate geographical area. These other smaller caves, despite being in the same intensely karstified limestone hill, seem to be mere satellites of the great habitat and decorative complex centred on El Castillo. They were occupied more occasionally as camps, for meetings and diverse activities, some of which would have involved the production of cave art.

After the first studies in the cave, the vestibule of Castillo was excavated by the Institut de Paleontologie Humaine at Paris, directed by H. Obermaier and H. Breuil, between 1910 and 1914. The cave art was studied at the same time, with the collaboration of Alcalde del Río and several foreign archaeologists. This work played a vital role in the definition of the Palaeolithic cultural sequence in the Cantabrian region, due both to the good state of conservation of the archaeological deposit and to its great thickness. Layers corresponding to nearly all the periods of the Palaeolithic were dug, reaching over 20m in depth. Furthermore, the documentation of the cave art inside the cave, where there are many complex panels with superimpositions of figures in different techniques and styles, was also important for the model of the chronology of cave art elaborated by Henri Breuil. This model, based on a succession of technical procedures and stylistic changes throughout the Upper Palaeolithic, was the main one used in chronological studies until 1965, when Leroi-Gourhan published his major work. Nowadays, the panels of figures in El Castillo are still proof of the distribution of many assemblages of cave art through millennia of decoration, despite the interpretations of some structuralist prehistorians, who tend to consider that all these complex panels are synchronic, or that the superimpositions are a form of composition.

Photo: César. González Sainz & Roberto Cacho Toca, Department of Historical Science, University of Cantabria

Text: http://www.muse.or.jp/spain/eng/cantabria/castillo/castillo_top.html

Hand stencils in El Castillo Cave may be older than thought.

Archaeologists Alistair Pike of Bristol University in England and João Zilhão of the University of Barcelona in Spain and their colleagues used the uranium-thorium technique to date 50 paintings and engravings from 11 cave sites in Asturias and Cantabria. They did this by collecting samples of the thin crusts of calcium carbonate that formed atop the images through the same process that forms stalactites and stalagmites. The crusts incorporate small amounts of uranium, which decays into thorium over time. By analysing the amount of thorium in a sample using a mass spectrometer, the researchers could determine how much time had passed since the crusts formed, thereby providing a minimum age for the images underneath.

Intriguingly, some of the paintings were significantly older than suspected. Experts thought that Spanish cave art was younger than French cave art. But the new results reveal one of the images at El Castillo - a large red disk on the Panel de las Manos - is at minimum 40 800 years old, making it some 4 000 years older than the Chauvet paintings, which were previously thought to be the oldest in the world. (Claims for comparably ancient cave art from Australia and India are not widely accepted on present evidence.) Other surprisingly old Spanish paintings identified in the study included a hand stencil from the Panel de las Manos that dates to at least 37 300 years ago and a club-shaped symbol from the famous Altamira cave that dates to 35 600 years ago at minimum.

Pike, Zilhão and their collaborators observe that the new results are consistent with the idea that the complexity of art increased gradually over time. The earliest dates they obtained were for non-figurative art - disks, hand stencils, and such - rendered in a single colour. Only later did people paint animals and use pigments of multiple hues.

But the team’s findings raise important questions about the artists behind the oldest paintings. The researchers note that anatomically modern humans arrived in western Europe around 41,500 years ago and thus may well have made the ancient Spanish paintings. But 42 000 years ago the only humans in Europe were Neandertals. In a press teleconference, Zilhão asserted that any art there that turns out to be older than 42 000 years must necessarily be attributed to Neanderthals. He and Pike suspect that the red disk and hand stencil at El Castillo might well be Neanderthal paintings, considering that the uranium-thorium dating results are minimum estimates, though Zilhão cautions that they haven’t proved it. The researchers are currently looking at additional sites in western Europe to see if they can get dates older than 42 000 years ago. (Some scientists think modern humans arrived in Europe as early as 45 000 years ago - a claim that Zilhão says is unwarranted based on the available evidence.)

Photo: Pedro Saura

Text: http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2012/06/14/oldest-cave-paintings-may-be-creations-of-neandertals-not-modern-humans/

Uranium-thorium dating, also called thorium-230 dating, uranium-series disequilibrium dating or uranium-series dating, is a radiometric dating technique commonly used to determine the age of calcium carbonate materials such as speleothem or coral. Unlike other commonly used radiometric dating techniques such as rubidium-strontium or uranium-lead dating, the uranium-thorium technique does not measure accumulation of a stable end-member decay product. Instead, the uranium-thorium technique calculates an age from the degree to which secular equilibrium has been restored between the radioactive isotope thorium-230 and its radioactive parent uranium-234 within a sample.Text above from Wikipedia.

Thorium is not soluble in natural waters under conditions found at or near the surface of the earth, so materials grown in or from these waters do not usually contain thorium. In contrast, uranium is soluble to some extent in all natural waters, so any material that precipitates or is grown from such waters also contains trace uranium, typically at levels of between a few parts per billion and few parts per million by weight. As time passes after the formation of such a material, uranium-234 in the sample decays to thorium-230, with a half-life of 245 000 years. Thorium-230 is itself radioactive with a half-life of 75 000 years, so instead of accumulating indefinitely (as for instance is the case for the uranium-lead system), thorium-230 instead approaches secular equilibrium with its radioactive parent uranium-234. At secular equilibrium, the number of thorium-230 decays per year within a sample is equal to the number of thorium-230 produced, which also equals the number of uranium-234 decays per year in the same sample.

Uranium-thorium dating has an upper age limit of somewhat over 500 000 years, defined by the half-life of thorium-230, the precision with which we can measure the thorium-230/uranium-234 ratio in a sample, and the accuracy to which we know the half-lives of thorium-230 and uranium-234. Note that to calculate an age using this technique the ratio of uranium-234 to its parent isotope uranium-238 must also be measured.

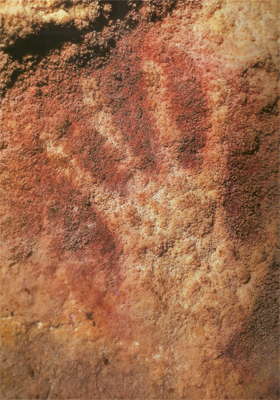

This undated photograph shows hand stencils at the El Castillo Cave in Spain, which uranium-series dating reveals to be earlier than 37 300 years ago, making them the oldest cave paintings in Europe. The practice of cave art in Europe thus began up to 10 000 years earlier than previously thought.

Photo and text: http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/33096646/ns/world_news-europe?q=Europe

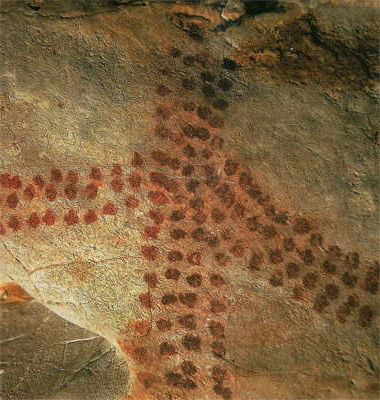

The 'Corredor de los Puntos' lies within Spain's El Castillo cave. Red disks here have been dated to between 34 000 and 36 000 years ago, and elsewhere in the cave to 40 800 years ago, making them examples of Europe's earliest cave art.

Photo and text: http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/33096646/ns/world_news-europe?q=Europe

This undated handout photo provided by Pedro Suara/AAAS shows the 'Panel of Hands', El Castillo Cave showing red disks and hand stencils made by blowing or spitting paint onto the wall. A date from a disk shows the painting to be older than 40 800 years making it the oldest known cave art in Europe. The bison overlay the hands and are therefore painted later. New tests show that the crude paintings of a red sphere and handprints are the oldest in the world, so ancient they may not have been by modern man. They might have even been made by the much - maligned Neanderthals, some scientists suggest but others disagree.

Photo: Pedro Saura / AAAS / Associated Press

Text: http://www.kfoxtv.com/ap/ap/top-news/spanish-cave-paintings-shown-as-oldest-in-world/nPWCQ/

Sketch of the paintings in the panel of hands.

Photo: http://apuntes.santanderlasalle.es/arte/prehistoria/franco_%20cantabrica/puente_viesgo.htm

Hands panel, El Castillo.

Photo: http://apuntes.santanderlasalle.es/arte/prehistoria/franco_%20cantabrica/puente_viesgo.htm

Right hand end of the hands panel, El Castillo.

Photo: http://apuntes.santanderlasalle.es/arte/prehistoria/franco_%20cantabrica/puente_viesgo.htm

Hands and bison, El Castillo.

Photo: http://apuntes.santanderlasalle.es/arte/prehistoria/franco_%20cantabrica/puente_viesgo.htm

Hands and signs, El Castillo.

Photo: http://apuntes.santanderlasalle.es/arte/prehistoria/franco_%20cantabrica/puente_viesgo.htm

Fifty paintings in 11 caves in Northern Spain, including the UNESCO World Heritage sites of Altamira, El Castillo and Tito Bustillo, were dated by a team of UK, Spanish and Portuguese researchers led by Dr Alistair Pike of the University of Bristol, UK.

As traditional methods such as radiocarbon dating don't work where there is no organic pigment, the team dated the formation of tiny stalactites on top of the paintings using the radioactive decay of uranium. This gave a minimum age for the art. Where larger stalagmites had been painted, maximum ages were also obtained.

Hand stencils and disks made by blowing paint onto the wall in El Castillo cave were found to date back to at least 40 800 years, making them the oldest known cave art in Europe, 5-10,000 years older than previous examples from France.

A large club-shaped symbol in the famous polychrome chamber at Altamira was found to be at least 35 600 years old, indicating that painting started there 10 000 years earlier than previously thought, and that the cave was revisited and painted a number of times over a period spanning more than 20 000 years.

Dr Pike said: 'Evidence for modern humans in Northern Spain dates back to 41 500 years ago, and before them were Neanderthals. Our results show that either modern humans arrived with painting already part of their cultural activity or it developed very shortly after, perhaps in response to competition with Neanderthals – or perhaps the art is Neanderthal art.'

The creation of art by humans is considered an important marker for the evolution of modern cognition and symbolic behaviour, and may be associated with the development of language.

Dr Pike said: 'We see evidence for earlier human symbolism in the form of perforated beads, engraved egg shells and pigments in Africa 70 - 100 000 years ago, but it appears that the earliest cave paintings are in Europe. One argument for its development here is that competition for resources with Neanderthals provoked increased cultural innovation from the earliest groups of modern humans in order to survive. Alternatively, cave painting started before the arrival of modern humans, and was done by Neanderthals. That would be a fantastic find as it would mean the hand stencils on the walls of the caves are outlines of Neanderthals' hands, but we will need to date more examples to see if this is the case.'

Photo: Pedro Saura

Text: http://phys.org/news/2012-06-iberian-europe-oldest-cave-art.html

Close up of one of the hands at El Castillo.

Photo: http://losvalientesduermensolos.blogspot.com.au/2011/10/cueva-el-castillo.html

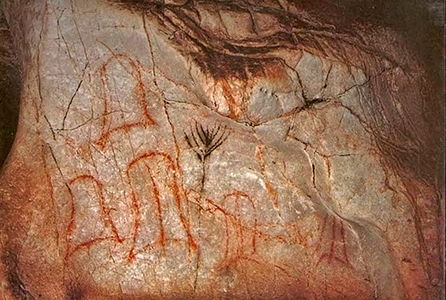

Bands of aligned red dots, each group of three or four dots arranged in rows.

A band of four dots form the vertical group and right group, and a band of three dots form the left.

(note that this image has been rotated 180° to conform with the image below by Heinrich Wendel - Don )

Photo: http://losvalientesduermensolos.blogspot.com.au/2011/10/cueva-el-castillo.html

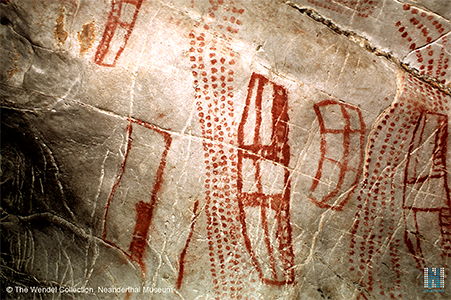

The shape, like many such signs, is enigmatic.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

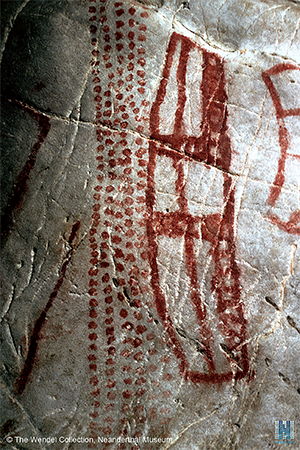

This sign forms what may be thought of as a cross, but made up of several elements, including squares which line the edges of the figure.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

This is a close up of the 'cross'.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

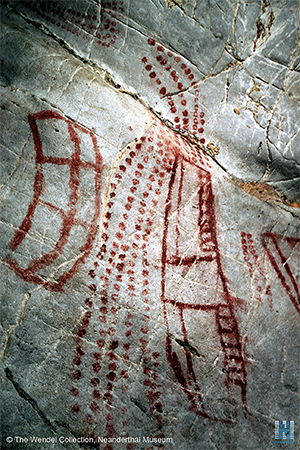

Similar signs are shown here, with squares on one side of a curved 'rectangle'.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

In addition there is a band of five lines of dots not always aligned with each other from side to side.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

The signs are painted in red ochre, high up on the wall of the cave.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

As well as the painted figures, several overlapping engravings may be seen on the walls and roof of the cave.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

Part of this section of signs could almost be interpreted as the torso of a human figure, however unlikely that is.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

On a rib of the roof may be seen images of a horse and possibly a deer, with an enigmatic design on the far wall, again decorated on one side with a row of squares.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

Source: El Castillo, Rincon de los Tectiformes, the Tectiform corner.

Signs, El Castillo.

The signs in red are a common representation of vulvas, denoted by Leroi-Gourhan (1973)

as type B1 Normal.

Photo: http://apuntes.santanderlasalle.es/arte/prehistoria/franco_%20cantabrica/puente_viesgo.htm

Mammoth at El Castillo

Photo: http://grupos.unican.es/arte/ingles/prehist/paleo/k/Default.htm

Horses at Tito Bustillo Cave dated by the same method.

Two metre long paintings of horses in Spain's Tito Bustillo Cave overlay earlier red paintings that, from dating elsewhere in the cave, might be older than 29 000 years.

The tests were conducted on 50 Paleolithic paintings in 11 Spanish caves, including the famous pictures of horses and human hands at the Altamira and El Castillo caves. In the past, the paintings have been dated using radiocarbon tests, but Pike's team used a different technique that analyzed the proportions of uranium, thorium and related elements in the calcite deposits that formed above and below the paintings. Those proportions vary over time, due to radioactive decay, and can tell you how long it's been since the calcite was formed.

That's an interesting approach for several reasons: First, the scientists don't have to depend on getting a reading from the paint itself, which may be contaminated or may not even be amenable to carbon dating. Also, the calcite deposits are scraped away, using a knife or a drill, until the pigment just begins to appear beneath it. "That does two things," Pike explained. "It means we stop before we damage the painting, and secondly it proves to us and our audience that these things are directly above the art itself."

The scientists can thus be confident that the age they get will be the minimum age for the artwork. In some cases, the scientists could sample flowstone deposits beneath the layer of paint to get a maximum age as well.

The tests took advantage of the state of the art in mass spectrometry, which means the scientists didn't require much of a sample. The scrapings amounted to as little as 10 milligrams, which is about the weight of a grain of rice. "Perhaps 20 years ago, we would have needed a whole gram of material, and now we need one-hundredth of that size," Pike said.

That minimizes the impact on the caves, which is a sensitive topic for the officials in charge of the caves. "Getting permission to work in a cave is really difficult," Snow explained. "The bureaucratic and political difficulties of getting this work done are substantial."

Pike and his colleagues pioneered this process years ago, in a project aimed at verifying the dates for 12,800-year-old cave engravings in England's Creswell Crags, but the tests reported today represent the highest-profile application of what's known as uranium-series disequilibrium dating.

Photo: Rodrigo De Balbin Behrmann

Text: http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2012/06/14/12211397-new-dating-method-shows-cave-art-is-older-did-neanderthals-do-it?lite

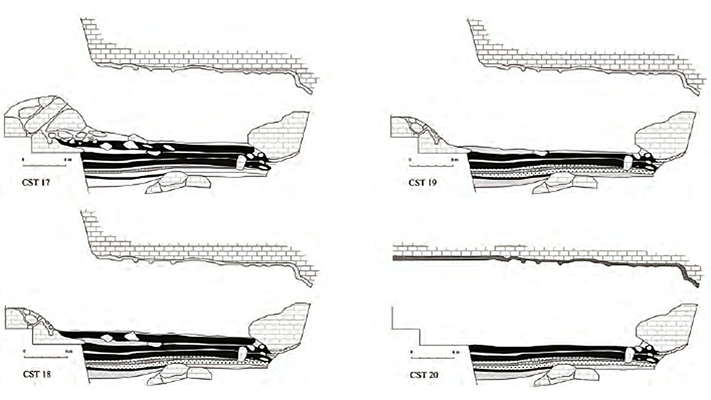

Theoretical framework of the formation of the layers of deposition in the cave.

From a stratigraphic viewpoint, the 18 group, subdivided into 18a, 18b and 18c is in between two sterile units (17 and 19) which are the result of the collapse of the cornice of the cavity.

Photo: Bernaldo de Quirós et al. (1999)

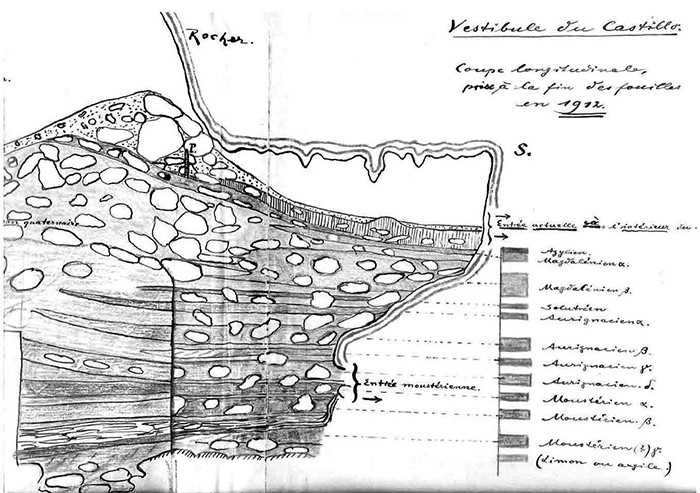

Stratigraphic section (coupe) of the Castillo excavation drawn by Hugo Obermaier at the end of the 1912 campaign.

Photo and text: Lanzarote Guiral (2011)

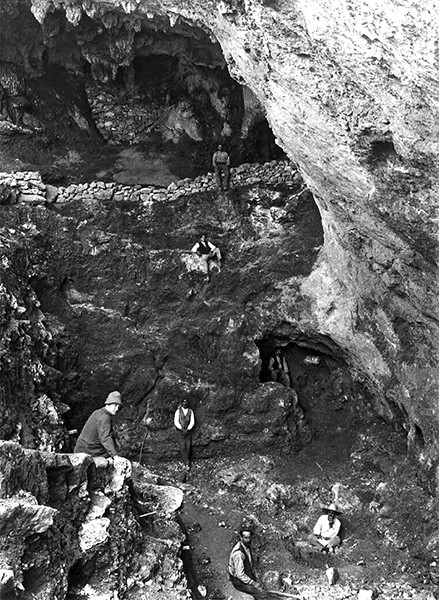

23rd July 1909, at the entrance to the grotte du Castillo

left to right: Abbés Henri Breuil and Hugo Obermaier (at the rear), the painter Louis Tinayre, and Alcalde del Rio. Behind them, two unnamed workmen. Prince Albert 1st of Monaco on the far right.

Prince Albert funded the dig, and took a keen interest in archaeology. Louis Tinayre (1861–1942) was a French illustrator and painter. He did panoramas and dioramas of Madagascar, and paintings of Albert I, Prince of Monaco, on his hunts around the world. ( Tinayre is shown here making a sketch of the Prince. - Don )

Photo and text: Lanzarote Guiral (2011)

Additional text: Wikipedia

Hugo Obermaier

Photo: Hugo Obermaier Gesellschaft

Source: Hugo Obermaier Archive, c / o Institute for Prehistory and Early History, University of Erlangen

Proximal source: http://www.obermaier-gesellschaft.de/lightbox/archiv1921.html#close

Excavations at El Castillo. Stratigraphic section of the Great Trench opened by Obermaier and his team, photographed during the campaign of 1913.

Obermaier in the left foreground.

Photo and text: Lanzarote Guiral (2011)

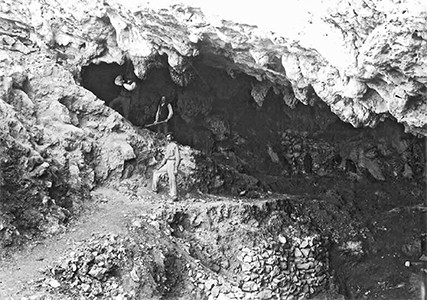

Excavations at El Castillo during the campaign of 1913.

The man in the foreground wearing light coloured clothes in this photograph is Alejandro Mena Garay, right hand man of Obermaier and chief of the Spanish digging workers.

( My sincere thanks for this useful identification to Alejandro Mena Campuzano, his great grandson, p.c. - Don )

Photo and text: Lanzarote Guiral (2011)

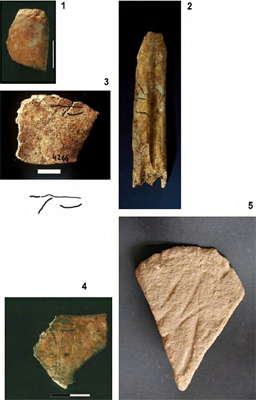

Bone industry at the 18c level of El Castillo.

Photo: Bernaldo de Quirós et al. (1999)

Bone and sandstone plaque industry from Level 18b.

Photo: Bernaldo de Quirós et al. (1999)

General view of the cave of El Castillo with an indication of the main stratigraphic units.

Photo: Bernaldo de Quirós et al. (1999)

References

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites