Back to Don's Maps

Overview of Cave Paintings and Sculptures

Sites in France

Photo:

Jaubert (2008)

A map of decorated caves in western Europe with the names of a few notable or outlying sites. The broken line encloses caves decorated in the distinctive 'Mediterranean Style' which seems to have been little influenced by the master artists of France and Spain. It often features simple, stark animal representations together with quite elaborate geometrical designs. There are important caves decorated in the Mediterranean style in southeast Spain, the Ardèche canyons in southern France, the heel of Italy, and in Sicily.

A map of decorated caves in western Europe with the names of a few notable or outlying sites. The broken line encloses caves decorated in the distinctive 'Mediterranean Style' which seems to have been little influenced by the master artists of France and Spain. It often features simple, stark animal representations together with quite elaborate geometrical designs. There are important caves decorated in the Mediterranean style in southeast Spain, the Ardèche canyons in southern France, the heel of Italy, and in Sicily.

There are now some 200 Painted caves known in southern France and northern Spain. Several new discoveries in the remote Spanish Basque country appear to be closing the gap between these two main regional groups which, in any case, certainly share many correspondences of style and theme.

But there are also outliers located far away from the major centers of activity-the engravings in the cave of Gouy near Rouen, for example, almost at the present shores of the English Channel. Three crude engravings on bone were recovered from cave entrances at Creswell Crags in the Derbyshire county of central England, dating perhaps as far back as 13 000 BC. There is no reason why cave artists should not have left paintings there or elsewhere in England, although no such traces have been found. Perhaps the sharper climate of the north has obliterated ancient cave walls through the natural forces of erosion more effectively than farther south.

In some regions of Europe where caves were absent - such as Moravia and Ukraine - rich traditions of engraving and sculpting in bone and ivory flourished. A detailed knowledge of these carving traditions is just beginning to be acquired by scholars in the west. And there are surprises in store for those interested in such regions: for example, the isolated painted cave discovered at Kapova in the Ural Mountains is, so far, the only one of its kind in the whole of eastern Europe. A number of animals painted in red ochre were identified in the Kapova cave, although the style is quite different from those of the west.

Photo and text: 'Secrets of the Ice Age' by E. Hadingham

One of the bisons on the ceiling of Altamira in Spain, representing the final stage of polychrome art in which four shades of colour are used.

One of the bisons on the ceiling of Altamira in Spain, representing the final stage of polychrome art in which four shades of colour are used.

Photo: M. Burkitt 'The Old Stone Age' (1955), after Breuil.

A view near the cave entrance, which is under trees on the skyline in the centre of the photograph. To the right, the ground drops down to the valley of the river Saja.

A view near the cave entrance, which is under trees on the skyline in the centre of the photograph. To the right, the ground drops down to the valley of the river Saja.

Photo from "Secrets of the Ice Age" by Evan Hadingham.

The following is condensed and adapted from 'Cro-Magnon Man' by T. Prideaux:

In 1868 a hunter's dog chased a fox across hilly countryside about 15 miles inland from the port of Santander on the Atlantic coast of Spain. The dog fell among some boulders. When the hunter rescued the dog, he saw the entrance to a cave.

Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola's daughter Maria

Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola's daughter Maria

The owner of the estate was a Spanish Nobleman and amateur archeologist, Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola (1831 - 88). The paintings were not discovered until November 1879 when the Don's daughter Maria, aged 5 to 9 years old, looked up from where the Don was digging for tools, and saw a herd of red animals spread across the ceiling. 'Mira, Papa, bueyes!' (Look, Papa, oxen!) she exclaimed.

Photo: Bahn (1998)

The colours have lasted because they were made from permanent natural earth pigments which are minerals, and do not decay. The iron minerals give the reds, yellow and browns, while manganese dioxide gives the blacks. They were 'fixed' by mixing them with blood, animal fat, urine, fish glue, egg white or vegetable juices.

For forty years it was the world's foremost showplace of historic art, until its replacement in this respect by the cave of Lascaux.

Photo: Bahn (1998)

Photo: Bahn (1998)

Henri Breuil (1877 - 1961). Although he trained as a priest in his youth, and remained a priest till he died, he never practised his profession. Instead he was allowed by the church hierarchy to devote his whole life to the study of prehistory. He was the son of a lawyer, and was guided in his studies by a teacher at the seminary who expounded the theory of evolution to him, and lent him books by Gabriel de Motillet, the anticlerical prehistorian.

Photo: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham, 1980

Photo: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham, 1980

Left, the Abbé Breuil (wearing cassock) photographed at El Castillo, northern Spain, in July 1909, with his patron, the Prince of Monaco (sitting at right).

Breuil had a talent for drawing animals, and was co-opted by prehistorians to help with the illustration of paleolithic portable and cave art. He became the world's leading authority on paleolithic art until his death. He spent about 700 days of his life underground, exploring and painting. In some cases his drawings and tracings are the only record left of paintings that have since faded or disappeared.

Photo: J. Powell 'Ancient Art'

Lascaux: Paintings in the main hall.

Photo: J Pfeiffer 'The Creative Explosion'

Lascaux: (Corrèze), salle des Taureaux. Premier et deuxième taureaux.

Lascaux. Room of the Bulls.

First and second bulls.

Photo from: Agenda de la Préhistoire 2002 - 2003, a superb diary with excellent illustrations sent to me by Anya. My thanks as always.

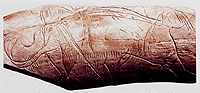

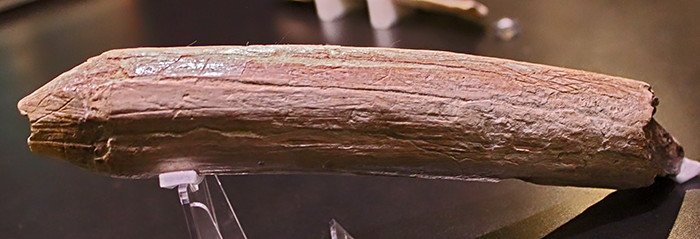

The world's oldest engraving on an ox rib from Pech de l'Azé in the Dordogne region, dating to the early part of the Riss glaciation. There are many other markings on the bone, most of which were probably due to naturally caused damage in the ground. The bone is nearly 17 centimeters long and may date to about 200 000 B.C.

![]() Grotte de Belvis (Aude) - Magdalénien supérieur récent - 12 270 ± 270. Grue gravée sur un tronçon de côte d'ongulé (longueur : 13,5 cm). Faut-il voir une évocation de la saison, retour du printemps ou venue de l'automne, dans cette figuration du grand migrateur ?

Grotte de Belvis (Aude) - Magdalénien supérieur récent - 12 270 ± 270. Grue gravée sur un tronçon de côte d'ongulé (longueur : 13,5 cm). Faut-il voir une évocation de la saison, retour du printemps ou venue de l'automne, dans cette figuration du grand migrateur ?

Grotte de Belvis (Aude) - recent higher Magdalenien - 12 270 ± 270 BP. Crane engraved on a section of bone (length: 13.5 cm). Is it possible to see an evocation of the season, the return of spring or the arrival of the autumn, in this depiction of a large migratory bird?

Station de Gönnersdorf (Rhénanie-Palatinat) - Magdalénien supérieur - vers 12 600 - Ces silhouettes féminines, sans tête ni bras, gravées sur une plaquette de schiste (11,8 x 10,8 cm), se distinguent, par leur remplissage de traits, des quelques 400 autres figurations de femmes mises au jour sur ce site.

Station de Gönnersdorf (Rhénanie-Palatinat) - Magdalénien supérieur - vers 12 600 - Ces silhouettes féminines, sans tête ni bras, gravées sur une plaquette de schiste (11,8 x 10,8 cm), se distinguent, par leur remplissage de traits, des quelques 400 autres figurations de femmes mises au jour sur ce site.

Station of Gönnersdorf (the Rhineland-Palatinat) - higher Magdalénien - around 12 600 BP - These female silhouettes, without head or arms, are engraved on a schist plate (11,8 X 10,8 cm), are distinguished by their shading, as for some 400 other depictions of women on this site. At this site there is a walkway between two huts, with the female figurines in one of them. This is believed by some to be a female initiation site.

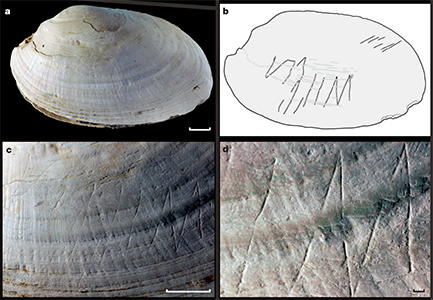

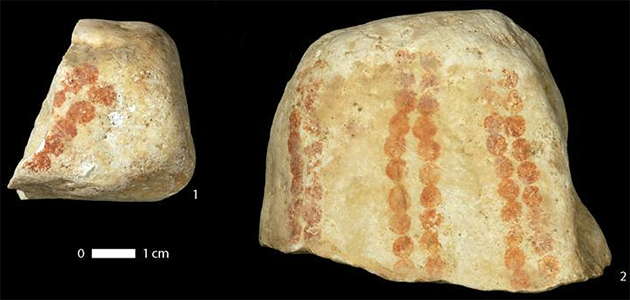

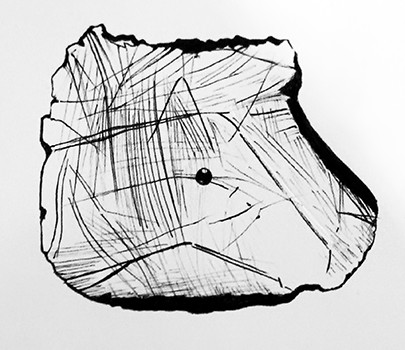

Geometric scratches on molluscs by Homo erectus at Trinil on Java.

What the investigators have is a jumble of clam shells, found in the strata where Homo erectus bones have been found elsewhere. These shells have been modified - the inference is that Homo erectus was living along the shore, gathering clams, and popping them open to eat.

First, evidence of tool use. Many of them have small holes, precisely gouged into the shells at a specific location, and these holes do not resemble in detail the damage done by other mollusc-eating animals. The closest thing to the kind of damage done in these shells was made by using a shark tooth (common in the area), and twisting the point against the shell.

Second, they knew something about these molluscs. The holes were punched precisely above the attachment point for the adductor muscle, the big muscle that clams use to clamp their shells shut. Experimenting with modern clams, the authors found that one small hole above that attachment would damage the adductor, so the shell would easily open.

And finally, doodler. One of the shells had some remarkable markings engraved on the inside - straight lines and a rough geometric pattern. The authors are quick to say there is no reason to justify calling this art, or something of religious significance, the two usual explanations trotted out for ancient paintings. I’m going to go out on a limb here, though, and suggest that our mighty clam hunter was doodling.

Photo: © Wim Lustenhouwer, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Joordens et al. (2015)

Text: Adapted from the inimitable PZ Myers, at http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2014/12/07/h-erectusdoodler/

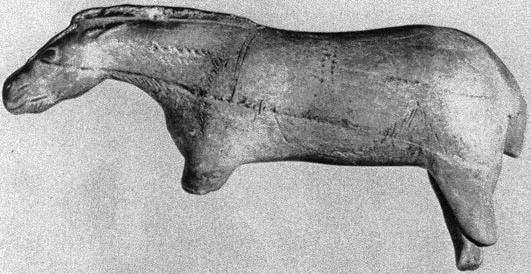

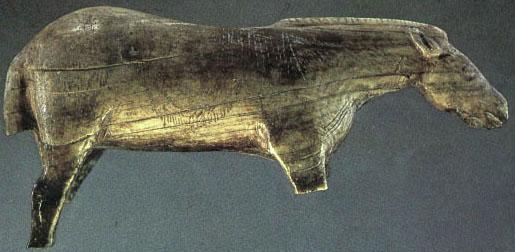

Side views and details of a re-assembled amber elk cow figurine from Weitsche.

This Late Palaeolithic amber figurine was skillfuly recovered and reassembled from a ploughed open site in northern Germany. Dated between 13 800 and 13 680 cal BP. It occupies a key point between the Magdalenian and the Mesolithic. The figurine represents a female elk which was probably carried on the top of a wooden staff.

Part of the amber figurine was first discovered in 1994 while prospecting at a site of the Federmesser culture, Late Glacial woodland hunters in the Elbe Valley, midway between Hamburg and Berlin, Germany. Here, flint artefacts are scattered over more than 60 Ha around the village of Weitsche, which makes this site one of the largest known settlement areas of the earliest woodland culture in north-western Europe. Systematic sieving of the adjacent arable soil between 1994 and 1998 and in 2003 yielded several concentrations of flint artefacts, fragments of calcined bone and, in particular, 49 fragments of amber scattered over approximately 100 m2 within a total investigated area of 700 m2

Photo: U. Bohnhorst

Compilation: S. Veil, © Landesmuseum, Hannover

Source: Veil et al. (2012)

Amber disk, Hamburg-Meiendorf, 12 000 BP.

This amber disk from Hamburg-Meiendorf engraved with a horse head can be interpreted as an amulet. Different images are suggested by the other lines.

Photo (left): Artist unknown, display at the museum

Photo (right): Ralph Frenken

Source: Original, exhibited at the Archeological Museum Hamburg (Ice Age - The Art of the Mammoth Hunters from 18 October 2016 to 14 May 2017)

Timonovka Russia, 15 000 BP.

This figure of mammoth ivory is very difficult to interpret and has been identified as a fish or a snake. The diamond-shaped indentations could represent scales, the pointed end an open mouth. Even slit-like eyes can be seen.

Photo: Ralph Frenken

Source: Original, exhibited at the Archeological Museum Hamburg (Ice Age - The Art of the Mammoth Hunters from 18 October 2016 to 14 May 2017)

On loan from the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Map of the location of the elk sculpture discovery.

Many of these fragments fitted to the original piece of amber, and step by step the rump of an animal took shape. On 21 September 2004, the head of the figurine was found, proving without doubt that it represents an elk cow. A pendant and a fragment of bead complete this assemblage of amber objects. All the artefacts were discovered within the ploughsoil, which lay to a depth of 250 mm. The Late Glacial surface was within this horizon: the amber artefacts did not come from a feature below the subsoil, like a pit or burial. A thin layer of fluvial loam had protected the amber against weathering.

Source: Veil et al. (2012)

First Neanderthal cave paintings discovered in Spain

12:20 10 February 2012 by Fergal MacErlean

Cave paintings in Malaga, Spain, could be the oldest yet found – and the first to have been created by Neanderthals.

Looking oddly akin to the DNA double helix, the images in fact depict the seals that the locals would have eaten, says José Luis Sanchidrián at the University of Cordoba, Spain. They have "no parallel in Palaeolithic art", he adds. His team say that charcoal remains found beside six of the paintings – preserved in Spain's Nerja caves – have been radiocarbon dated to between 43 500 and 42 300 years old.

That suggests the paintings may be substantially older than the 30 000-year-old Chauvet cave paintings in south-east France, thought to be the earliest example of Palaeolithic cave art.

The next step is to date the paint pigments. If they are confirmed as being of similar age, this raises the real possibility that the paintings were the handiwork of Neanderthals – an "academic bombshell", says Sanchidrián, because all other cave paintings are thought to have been produced by modern humans.

Neanderthals are in the frame for the paintings since they are thought to have remained in the south and west of the Iberian peninsula until approximately 37,000 years ago – 5000 years after they had been replaced or assimilated by modern humans elsewhere in their European heartland.

Until recently, Neanderthals were thought to have been incapable of creating artistic works. That picture is changing thanks to the discovery of a number of decorated stone and shell objects – although no permanent cave art has previously been attributed to our extinct cousins.

Now some researchers think that Neanderthals had the same capabilities for symbolism, imagination and creativity as modern humans.

The finding "is potentially fascinating", says Paul Pettitt at the University of Sheffield, UK. He cautions that the dating of cave art is fraught with potential problems, though, and says that clarification of the paintings' age is vital.

"Even some sites we think we understand very well such as the Grotte Chauvet in France are very problematic in terms of how old they are," says Pettitt.

If the age is confirmed, Pettitt suggests that the cave paintings could still have been the work of modern humans. "We can't be absolutely sure that Homo sapiens were not down there in the south of Spain at this time," he says.

Sanchidrián does not rule out the possibility that the paintings were made by early Homo sapiens but says that this theory is "much more hypothetical" than the idea that Neanderthals were behind them.

Dating of the Nerja seal paintings' pigments will not take place until after 2013. Further excavations in the extensive cave system – discovered by a group of boys hunting bats in 1959 – is ongoing.

Photo: Nerja Cave Foundation, http://dienekes.blogspot.com/

Text: http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn21458-first-neanderthal-cave-paintings-discovered-in-spain.html%7CFirst

Related story:

Three tools dating from 40 000 years ago have been found in the caves

The confirmation that three flint tools date from 40 000 years ago confirms the fact that the Nerja Cave (Málaga province) was inhabited by Neanderthal man. A group of scientists have been looking at items removed from the famous grotto some 20 years ago and say that there is no doubt about the evidence.

The tools date from the middle Palaeolithic period and are part of 151 588 items which have been newly classified in an operation led by Antonio Garrido. The news was released to the press yesterday by the Nerja Cave Foundation. Director, Ángel Ramírez, said that the news marks a key day in the history of the cave, and that it was exciting to know that that the municipality was witness to one of the most relevant prehistoric times.

Text: http://www.typicallyspanish.com/news/publish/article_12710.shtml

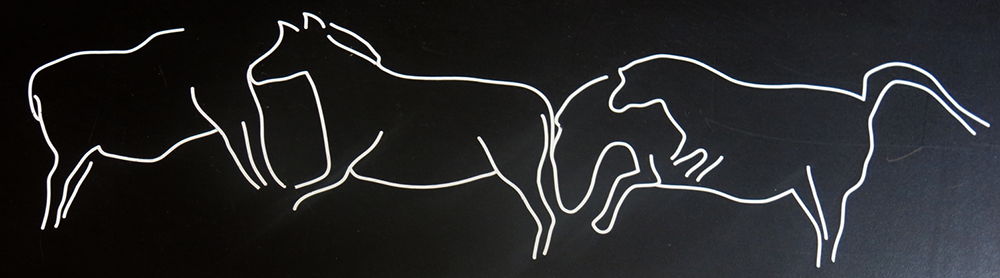

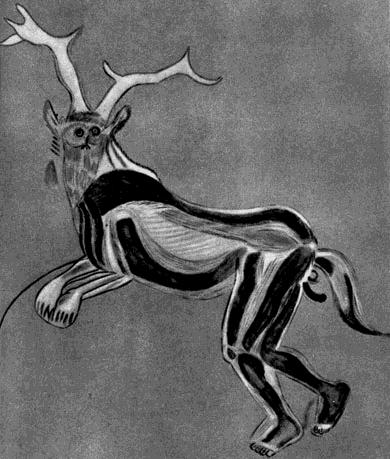

Palaeolithic animal paintings foreshadow the cinema

By Julie Clayton, Heritage Portal

Reporting in the current issue of Antiquity, Marc Azéma and Florent Rivère describe their findings of numerous examples of cave drawings in which multiple images of animals such as bison, horses and lions are superimposed upon one another as if to suggest movement – for example of the head, tail or legs. A video link shows the animated sequence of a horse, for example, lifting and lowering its head. There are 20 such images in the French cave of Lascaux alone. Each stroke of the artist’s drawing implies a breakdown of sequential movements of the same animal, according to the authors.

'To me it’s obvious that the images are not static, but dynamic,' says Azema in an interview with Heritage Portal. 'I think the artists were fascinated by the natural movement of animals and tried to reproduce this as an expression of life.'

When Azema began his studies of cave art more than 20 years ago he saw that other scholars were more preoccupied with the detailed representations and composition of cave art, and its symbolism. “Animation was a secondary question,” he notes. Azema’s view is that rather than being symbolic, the Palaeolithic images were intended to be a naturalistic narrative depiction of life events over time, perhaps with an educational or allegorical message.

Supporting this hypothesis is the discovery of a sandstone plaque in 1940 bearing the image of a deer on either side, one standing, and the other lying down, possibly dying, and the finding of Magdalenian discs made of bone in the Pyrenees, the north of Spain and the Dordogne, displaying slightly different versions of the same animal image on either face. Azema and Rivère tested the possibility that the discs were used as a device for animation by suspending a replica with string and rotating them around a lateral axis to reveal flickering images of moving animals.

'Thus, the Palaeolithic artists invented an optical toy, whose principle was to be found again with the invention of the thaumatrope in 1825, which is itself the direct ancestor of the cinematic camera' the authors conclude.

The above text is itself adapted from:

Azéma and Rivère (2012) and Azéma (2009)

Engraved Teeth

Grotte de La Marche (Vienne) - Magdalénien moyen - Incisive de cheval ornementée d'un motif triangulaire gravé à connotation sexuelle féminine évidente (longueur : 5 cm environ)

Grotte de La Marche (Vienne) - Magdalénien moyen - Incisive de cheval ornementée d'un motif triangulaire gravé à connotation sexuelle féminine évidente (longueur : 5 cm environ)

Grotte de La Marche (Vienna) - middle Magdalenien - Incisor horse tooth ornamented with an engraved triangular motif with obvious female sexual connotation (length: approximately 5 cm)

Grotte Gazel (Aude) - Magdalénien moyen - 15070 ± 270 Éléments de parure; de gauche à droite: incisive de renne, incisive de lièvre, canine de renard, canine de cerf. (long.; 2 cm)

Grotte Gazel (Aude) - Magdalénien moyen - 15070 ± 270 Éléments de parure; de gauche à droite: incisive de renne, incisive de lièvre, canine de renard, canine de cerf. (long.; 2 cm)

Grotte Gazel (Aude) Some ornamentation; Middle Magdalenien - 15070 ± 270 From left to right: incisor of reindeer, incisor of hare, canine of fox, canine of stag. Length 2 cm.

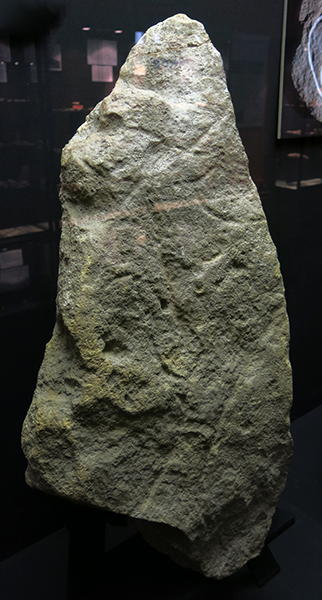

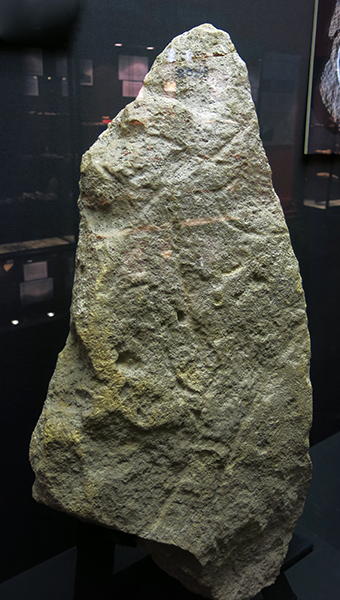

Le Masque Moustérien de la Roche-Cotard à Langeais (Indre-et-Loire)

The site of la Roche-Cotard was discovered at the beginning of the 20th century but the Mousterien level (Roche-Cotard II), located in front of the opening of the cave, has been known only for 25 years.

The site of la Roche-Cotard was discovered at the beginning of the 20th century but the Mousterien level (Roche-Cotard II), located in front of the opening of the cave, has been known only for 25 years.

In this dwelling site a very special object undoubtedly prepared by humans was discovered: it is a flint having a natural hole in which a small piece of bone has been placed. This object which makes one think of a human or animal face is an exceptional witness of the slow advance of humanity towards the beginning of illustrated art.

Text: By Jean-Claude Marquet, http://ma.prehistoire.free.fr/masque.htm

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Facsimile, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

The only dating obtained for this Mousterien site (which contained some rare tools) from the fragments of bone gives 32 000 years "or more".

"The Mask" consists of a small flat flint which was modified to accentuate its resemblance to a face:

(1) a small piece of bone was inserted in a natural hole in the stone and fixed by two small stones;

(2) the stone was then improved to obtain greater symmetry.

'The Mask' is regarded as 'a proto-figurine', one of the first steps towards the art of the upper Paleolithic. It is an exceptional object because the mousterian culture is not known to give this type of artistic production.

If Mousterian civilization is specific to Neandertals in Europe, "the Mask" thus leads us to think that Neandertals were capable of an artistic production more advanced than than anyone suspected until now.

This protofigurine is a flint improved by Mousterians to accentuate the appearance of a face which the stone offered.

Version française

Le site de la Roche-Cotard a été découvert au début du XXe siècle mais le niveau moustérien (La Roche-Cotard II), situé devant l'ouverture de la grotte, n'est connu que depuis 25 ans.

Le site de la Roche-Cotard a été découvert au début du XXe siècle mais le niveau moustérien (La Roche-Cotard II), situé devant l'ouverture de la grotte, n'est connu que depuis 25 ans.

Dans ce niveau d'habitation a été découvert un objet très spécial indubitablement préparé par l'Homme : c'est un silex possédant un trou naturel dans lequel est placée une petite esquille d'os. Cet objet qui fait penser à une face humaine ou animale est un témoin exceptionnel du lent cheminement de l'humanité vers l'avènement de l'art figuré.

La seule datation obtenue pour ce niveau moustérien qui contenait quelques rares outils et des fragments d'os donne 32000 ans "ou plus".

Le "Masque" consiste en un petit silex plat qui a été modifié pour accentuer sa ressemblance avec un visage :

(1) un petit éclat d'os a été inséré dans un orifice naturel de la pierre et calé par deux petites pierres ;

(2) la pierre a été ensuite retouchée pour obtenir une symétrie.

Le "Masque" est considéré comme une "proto-figurine", l'un des prémices vers l'art du Paléolithique supérieur. C'est un objet exceptionnel car la culture moustérienne n'est pas connue pour donner ce type de production artistique.

Si la civilisation moustérienne est bien comme on le croit spécifique de l'Homme de Neandertal en Europe, le "Masque" donne ainsi à penser que les Néandertaliens étaient capables d'une production artistique plus évoluée que ce que l'on soupçonnait jusqu'à présent.

Cette protofigurine est un silex retouché par des Moustériens pour accentuer l'apparence de visage qu'offrait la pierre.

Chauvet Cave

Chauvet Cave

These portraits of humans are engravings on stone slabs at La Marche, Vienne, France, and are more than 14 000 years old.

Grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne), Tête humaine vue de face, Grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les Châteaux (Vienne). Tête humaine avec ornement facial. Très profondément incisés, des traits de gravure parallèles couvrent la joue. Il peut s'agir de peintures corporelles ou de scarifications.

Grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne), Tête humaine vue de face, Grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les Châteaux (Vienne). Tête humaine avec ornement facial. Très profondément incisés, des traits de gravure parallèles couvrent la joue. Il peut s'agir de peintures corporelles ou de scarifications.

Grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne, France). Human head with facial ornament. Very deeply incised, with parallel lines covering the cheek. They could be body paintings or scarifications.

Du côté gauche : grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne), Tête humaine vue de face, relevé sélectif. Ce visage a I'apparence de celui d'un homme âgé, peut-être un vieillard.

Du côté gauche : grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne), Tête humaine vue de face, relevé sélectif. Ce visage a I'apparence de celui d'un homme âgé, peut-être un vieillard.

On the left: Grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne, France). Face of what appears to be an old man.

Du côté droit : grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne). Têtes humaines affrontées, On remarque, en particulier, des éléments de coiffure : bonnets probablement.

On the right: Grotte de La Marche, Lussac-les-Châteaux (Vienne, France). Faces of two children wearing what appear to be hats.

Photos from: Agenda de la Préhistoire 2002 - 2003, a superb diary with excellent illustrations sent to me by Anya. My thanks as always.

A painted abri broken in fragments (Abri Blanchard, Sergeac).

The Aurignacians at the Abri Blanchard also painted the ceiling of their rock-shelter, which collapsed due to frost during the coldest period of the Wurm glaciation, thus shattering the decoration. On a large wall fragment, one can still read the black lines against a red background, which depict the limbs and ballooned stomach of an animal that probably represents a horse. The rest was destroyed. From 1910 to 1911, Abri Blanchard was studied by Louis Didon and his trusty excavator Marcel Castanet (Musee du Perigord).

Photo: 'Discovering Perigord Prehistory' by B & G Delluc, A Roussot & J Roussot-Larroque.

My thanks to Sharon Rogers/walkhound for alerting me to this excellent book.

Spearthrower made of antler showing a young ibex with an emerging turd on which two birds are perched, found around 1940 in the cave of Le Mas d'Azil, Ariege. The ibex figure is about 7 cm long, and dates to about 16000 BP.

Spearthrower made of antler showing a young ibex with an emerging turd on which two birds are perched, found around 1940 in the cave of Le Mas d'Azil, Ariege. The ibex figure is about 7 cm long, and dates to about 16000 BP.

This was one of the first examples of mass produced art. Fragments of up to ten examples of this design have been found, which means that scores or hundreds must have been manufactured originally. The joke must have been very popular amongst the people of the time!

Photo: Bahn (1998)

Phallus in carved ivory from Mas d'Azil, discovered by Édouard Piette.

Length 95 mm, Diameter 17 mm

This piece has two holes, leading observers to believe that it is a pendant. On the right, a close up of the 'whipping' denoted by carving.

Cat 359, MAN : 47042 (APM10503)

Photo (left): © photo - Loïc Hamon, Musée des Antiquités nationales, Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Photo Source: http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/app/eng/96ce1735.htm

Photo (right):

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/joconde_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_98=REF&VALUE_98=50010008046

At the distal phalliform end, a third, broken perforation could be the remains of the hole of a bâton percé.

Photo:

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/joconde_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_98=REF&VALUE_98=50010008046

Carving from La Madeleine in the Dordogne that probably served as the weighted end of a spear thrower. Note the peculiar bridle pattern on the muzzle. This is a good argument against similar patterns on horses being representations of halters.

Bison licking its shoulder, from La Madeleine

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Original on display at Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

Woolly Mammoth engraved on a plate of ivory found in the cavern of La Madelaine, Perigord

Photo: C. Lyell 'The Antiquity of Man' (1873)

Mammouth gravé sur un gros fragment d'ivoire de mammouth trouvé lors

des fouilles de l'abri-sous-roche de La Madeleine près des Eyzies par

Edouard Lartet en mai 1864. Photo H. Delporte.

Mammoth engraved on a large fragment of mammoth ivory found at the time of the excavations of the rock shelter of the Madeleine close of Eyzies by Edouard Lartet in May 1864. Photo H. Delporte.

Photo and French text: "les mammouths - Dossiers

Archéologie - n° 291 - Mars 2004"

My thanks to Anya for access to this resource.

Mammoth engraving from Florida

The bone with the engraving is a long bone, possibly from a mastodon or mammoth.

Photo: Chip Clark / Smithsonian

22nd June 2011

Researchers from the Smithsonian Institution and the University of Florida have announced the discovery of a bone fragment, approximately

13 000 years old, in Florida with an incised image of a mammoth or mastodon. This engraving is the oldest and only known example of Ice Age art to depict a proboscidean (the order of animals with trunks) in the Americas. The team’s research is published online in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

The bone was discovered in Vero Beach, Fla. by James Kennedy, an avocational fossil hunter, who collected the bone and later while cleaning the bone, discovered the engraving. Recognising its potential importance, Kennedy contacted scientists at the University of Florida and the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute and National Museum of Natural History.

Photo: Chip Clark / Smithsonian

"This is an incredibly exciting discovery," said Dennis Stanford, anthropologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and co-author of this research. "There are hundreds of depictions of proboscideans on cave walls and carved into bones in Europe, but none from America—until now."

The engraving is 3 inches (75 mm) long from the top of the head to the tip of the tail, and 1.75 inches (45 mm) tall from the top of the head to the bottom of the right foreleg. The fossil bone is a fragment from a long bone of a large mammal — most likely either a mammoth or mastodon, or less likely a giant sloth. A precise identification was not possible because of the bone’s fragmented condition and lack of diagnostic features.

"The results of this investigation are an excellent example of the value of interdisciplinary research and cooperation among scientists," said Barbara Purdy, professor emerita of anthropology at the University of Florida and lead author of the team’s research. "There was considerable skepticism expressed about the authenticity of the incising on the bone until it was examined exhaustively by archaeologists, paleontologists, forensic anthropologists, materials science engineers and artists."

One of the main goals for the research team was to investigate the timing of the engraving — was it ancient or was it recently engraved to mimic an example of prehistoric art? It was originally found near a location, known as the Old Vero Site, where human bones were found side-by-side with the bones of extinct Ice Age animals in an excavation from 1913 to 1916. The team examined the elemental composition of the engraved bone and others from the Old Vero Site. They also used optical and electron microscopy, which showed no discontinuity in coloration between the carved grooves and the surrounding material. This indicated that both surfaces aged simultaneously and that the edges of the carving were worn and showed no signs of being carved recently or that the grooves were made with metal tools.

Believed to be genuine, this rare specimen provides evidence that people living in the Americas during the last Ice Age created artistic images of the animals they hunted. The engraving is at least 13 000 years old as this is the date for the last appearance of these animals in eastern North America, and more recent Pre-Columbian people would not have seen a mammoth or mastodon to draw.

The team’s research also further validates the findings of geologist Elias Howard Sellards at the Old Vero Site in the early 20th Century. His claims that people were in North America and hunted animals at Vero Beach during the last Ice Age have been disputed over the past 95 years.

A cast of the carved fossil bone is now part of an exhibit of Florida Mammoth and Mastodons at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville.

Source: http://smithsonianscience.org/2011/06/bone-fragment-may-contain-only-known-ice-age-artwork-from-america-to-depict-a-proboscidean/

More on this artefact:

Text below from: 'Cro-Magnon Man' by T. Prideaux, an excellent introduction to the subject:

'By 1867, the march of archaeology reached a milestone in the grand Exposition Universelle in Paris. Sponsored by Napoleon 111, the big fair paid homage to industry and culture. It introduced an oddly ominous vehicle called a batteuse, or locomobile, that

was supposed to prove useful as a steam-driven thresher. The United States, though still shaken by the Civil War, sent a display of rubber goods, including a life raft, and a new drink-much sampled in the American bar on a gaslit promenade --- called a mint julep. As a bow to ancient culture, a replica was built of Egypt's Temple of Philae on the Nile. But far more ancient, and more astonishing, was a small but comprehensive exhibit of prehistoric artifacts, assembled from all over Europe.

The visitors peered at elegantly shaped flint lance heads from Dordogne and hand axes found in the Somme Valley. The real crowd-catcher was a collection of 51 pieces of prehistoric art, including an engraving of a mammoth on ivory, which had been found in 1864 by Lartet and Christy beneath a rocky overhang at La Madeleine near Les Eyzies. All over Paris people talked about it and the other examples of prehistoric art exhibited because the art obliged them to revise their hazy estimates of these primitive cave creatures. (One enthusiast offered a million francs for the collection.) Clearly, men capable of such controlled artistry could not be utter barbarians. But who were they? Where did they come from? What were they called?'

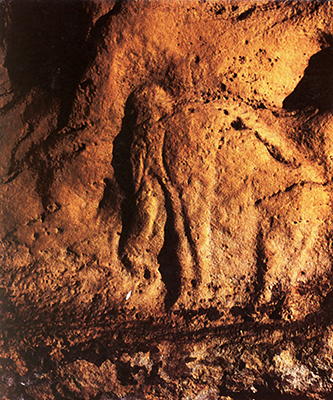

A metre long life size salmon, made on the overhang of Abri du Poisson in the Gorge d'Enfer is the only sculpted representation of a fish, an animal rarely depicted in cave art, although it appears more often in portable art.

A metre long life size salmon, made on the overhang of Abri du Poisson in the Gorge d'Enfer is the only sculpted representation of a fish, an animal rarely depicted in cave art, although it appears more often in portable art.

There was an attempt made once to steal this sculpture, and the thieves were disturbed at the point where they had put a series of holes around the sculpture ready to undercut it. This photo is probably of a well made cast of the original, since it appears to be free standing. Sharon Rogers tells me the original is still in place, on the ceiling of a small cave just south of Laugerie Haute.

Photo: 'Discovering Perigord Prehistory' by B & G Delluc, A Roussot & J Roussot-Larroque.

My thanks to Sharon Rogers/walkhound who alerted me to the existence of this excellent book.

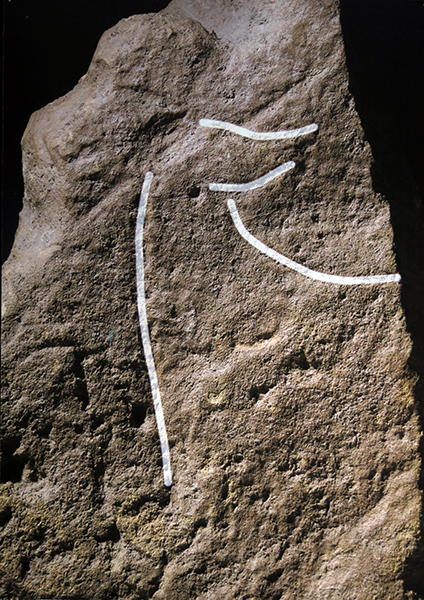

Abri Poisson, Perigordian engraving of a vulva.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Original, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

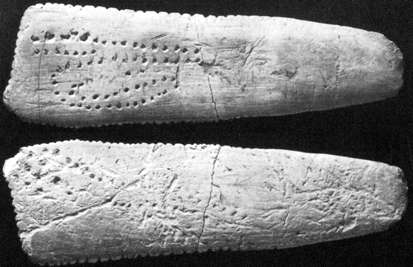

This is the famous lunar calendar from Abri Blanchard, carved from reindeer antler.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Probably a facsimile, Musée de la préhistoire à Sergeac

Another photograph of the lunar calendar.

Photo: Castanet (2006)

Explanation of the lunar calendar.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2008

Source: Display, Musée de la préhistoire à Sergeac

Bone plaque from the Abri Blanchard, Sergeac, France, with enlargement of the series of pits, suggested to indicate phases of the moon (drawing after Marshack, A. 1970. Notation dans les Gravures du Paléolithique Supérieur, Bordeaux, Delmas.) Colour photo: source unknown

The following text is from the useful book, 'The Prehistory of Europe' by Patricia Phillips, Allen Lane 1980:

A controversial but imaginative approach to Palaeolithic art has been used over the past decade by Alexander Marshack. This worker believes he has detected notation and symbolism in Upper Palaeolithic art. He investigates artifacts by means of a high-powered microscope, and is also working on the development of spectroscopic techniques for analysis of compositions in the painted caves. The majority of his published results concern mobiliary art; a more recent publication of his draws together evidence for symbolism in the Mousterian, which he regards as the background to the sophistication evident in the early Upper Palaeolithic.

One of Marshack's early reports concerned the lines of pits, strokes or notches cut into six bone or stone plaques of the Aurignacian period, housed at the Musée des Antiquités Nationales at St-Germain-en-Laye. He concluded that the pits occurred in multiples of thirty to thirty-one, and were produced by a series of techniques, for instance stabbing, curving to the left or to the right. In a bone plaque from the Abri Blanchard, Sergeac, Dordogne, in sixty-nine marks there were twenty-four changes in the type of pitting (see figure above). According to Marshack the type of technique changes with the different phases of the moon, when the moon becomes crescent-shaped, full or dark. The Abri Blanchard plaque bore eighty-one marginal marks which, in addition to the original sixty-nine, would comprise a record of about six months. Similar analysis suggested that the marks on both sides of a schist pebble from Barma Grande on the Riviera amounted to a total tally of fifteen months. A decorated bone bearing the design of a horse and rows of pits from La Marche, central France, bore a lunar notation of seven and a half months; the horse had been 're-used' several times. These markings could possibly have been used to represent the seasonal sequence of regional phenomena or economic activities, or ceremonies.

Ancient phallus unearthed in cave

By Jonathan Amos

BBC News science reporter

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4713323.stm

A sculpted and polished phallus found in a German cave is among the earliest representations of male sexuality ever uncovered, researchers say.

The 20cm-long, 3cm-wide stone object, which is dated to be about 28,000 years old, was buried in the famous Hohle Fels Cave near Ulm in the Swabian Jura.

The prehistoric "tool" was reassembled from 14 fragments of siltstone.

Its life size suggests it may well have been used as a sex aid by its Ice Age makers, scientists report.

"In addition to being a symbolic representation of male genitalia, it was also at times used for knapping flints," explained Professor Nicholas Conard, from the department of Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology, at Tübingen University.

"There are some areas where it has some very typical scars from that," he told the BBC News website.

Researchers believe the object's distinctive form and etched rings around one end mean there can be little doubt as to its symbolic nature.

"It's highly polished; it's clearly recognisable," said Professor Conard.

The Tübingen team working Hohle Fels already had 13 fractured parts of the phallus in storage, but it was only with the discovery of a 14th fragment last year that the team was able finally to put the "jigsaw" together.

The different stone sections were all recovered from a well-dated ash layer in the cave complex associated with the activities of modern humans (not their pre-historic "cousins", the Neanderthals).

The dig site is one of the most remarkable in central Europe. Hohle Fels stands more than 500m above sea level in the Ach River Valley and has produced thousands of Upper Palaeolithic items.

Female forms, such as the 30 000-year-old Venus of Willendorf are more common.

Some have been truly exquisite in their sophistication and detail, such as a 30 000-year-old avian figurine crafted from mammoth ivory. It is believed to be one of the earliest representations of a bird in the archaeological record.

There are other stone objects known to science that are obviously phallic symbols and are slightly older - from France and Morocco, of particular note. But to have any representation of male genitalia from this time period is highly unusual.

"Female representations with highly accentuated sexual attributes are very well documented at many sites, but male representations are very, very rare," explained Professor Conard.

Current evidence indicates that the Swabian Jura of southwestern Germany was one of the central regions of cultural innovation after the arrival of modern humans in Europe some 40,000 years ago.

The Hohle Fels phallus will go on show at Blaubeuren prehistoric museum in an exhibition called Ice Art - Clearly Male.

This sculpture depicts a water bird, perhaps a diver, cormorant or duck. The legs of the bird are short, but they lack feet, perhaps because to represent the bird in flight. The back is etched with a series of distinct lines representing feathers; 31 000 and 33 000 years old approximately; measures 47 x 13 x 9 mm; Hohle Fels, Germany

Photo and text: © Universität Tübingen

Source: http://i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/02470/BIRD_2470447k.jpg

Ice Age Paintings from the Swabian Jura, Southwestern Germany Document the Earliest Painting Tradition in Central Europe

Hohle Fels 2010. Two painted limestone cobbles with parallel lines of red dots.

ScienceDaily (Nov. 8, 2011) — Recent excavations conducted by the University of Tübingen at Hohle Fels Cave in the Swabian Jura of southwestern Germany have produced new evidence for the earliest painting tradition in Central Europe about 15 000 years ago. This period is referred to as the Magdalenian and is named after the site of La Madeleine in France.

Three of the new paintings show double rows of red dots on limestone cobbles, while one painted fragment may originate from the wall of the cave. These are the first examples of painted rocks recovered in Germany since 1998 when Prof. Nicholas Conard's team working at Hohle Fels discovered a single painted rock.

In addition to the painted rocks, finds of ochre and hematite that were used to make pigments have also been recovered.

Although Ice Age cave paintings are well documented in western Europe, particularly in France and Spain, wall paintings are unknown in central Europe. The lack of wall paintings at Hohle Fels in particular as well as in Central Europe as a whole may in part be a reflection of the harsh climate of the region that continually led to the erosion and damage to the walls of the caves.

The paintings from Hohle Fels Cave in the Ach Valley near Schelklingen document the oldest tradition of painting in central Europe. The painted limestone cobbles from Hohle Fels all show very similar motifs, and these rows of painted red dots certainly must have had a particular meaning to the inhabitants of the region. This being said, unlike the many examples of painting of animals in the Paleolithic art, these abstract depictions remain difficult to interpret.

Photo: Marina Malina, University of Tübingen, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/11/111108075401.htm

The rive Volp leaving the limestone cavern of Tuc d'Audoubert at Montesquieu-Avantès in the Province of Ariège, France.

Photo:

Breuil (1979)

Bison bull and cow, modelled in clay in the rotunda of the Tuc d'Audoubert, Ariege.

The sculptures are 63 and 61 cm long respectively from left to right. They probably cracked shortly after being made, as the clay dried. Although there are stalactites and stalgmites elsewhere in this cave system, there is no water dripping from the ceiling to destroy these sculptures. They are located at the very furthest point of a 900 metre cave, in a chamber reached only after an often uncomfortable and difficult journey.

Photo:

http://nanopatentsandinnovations.blogspot.com.au/2013/01/from-lands-time-forgot-eye-popping-mind.html

Count Bégouën and his three sons, photographed at the entrance to Le Tuc d'Audobert in 1912, shortly after the discovery of the clay bison.

Photo: Secrets of the Ice Age by Evan Hadingham

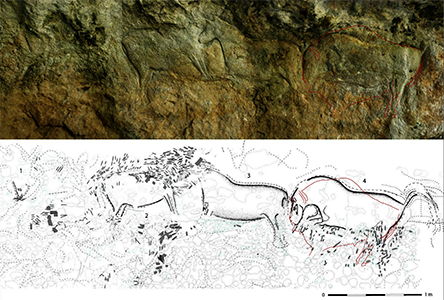

The frieze of horses at Chaire à Calvin.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

Sketch of the frieze of horses at Chaire à Calvin.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Display at Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

La Chaire à Calvin is a rock shelter near the village of Mouthiers-sur-Boëme in the Département of Charente, situated in the vallée du Gersac. The shelter is on a cliff which faces south east. The rock face of this rock-shelter has a sculpted frieze dated to the Magdalenian period; approximately 15 000 years BP.

This site was studied by Pierre David from 1924, he discovered the frieze in 1926, it was further studied by Bouvier in the 1960s. This site contains the remains of rhinoceros, red deer, beaver, wolf, Saiga Antelope, tarpan, reindeer and aurochs, as well as fox, hare and indeterminate birds. The remains of Saiga Antelope were the most numerous animal remains discovered. The only human remains discovered are a single molar.

Photo: rosier

Permission: GNU Free Documentation License

Source: Original, in situ

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

Frieze of horses at La Chaire à Calvin.

It appears that the frieze may have been enhanced in modern times to make the sculptures more obvious.

Photo: Heinrich Wendel (© The Wendel Collection, Neanderthal Museum)

The frieze includes depictions of an aurochs without its head, a pregnant tarpan, and a mating scene of tarpans. Some traces of orange-red paint were found when the frieze was discovered.

Artefacts found include bone needles, squared bone spear head; a shellfish necklace and some pearls. Stone artefacts include bladelets, chisels and scrapers.

John Calvin, the Presbyterian reformer, preached on a rock platform near this shelter when he was living in Angoulême in 1520.

Photo: http://www.sculpture.prehistoire.culture.fr/en/chaire-calvin.html#introduction-la-chaire-calvin

Source: Original, in situ

Text: Adapted from Wikipedia

This image includes a drawing of the animals engraved and sculpted in low relief on the wall.

Photo: http://www.sculpture.prehistoire.culture.fr

Entrance to the sanctuary of Trois Frères at Montesquieu-Avantès in the Province of Ariège, France.

Photo:

Breuil (1979)

Arcy-sur-Cure, mammoth.

Photo: http://prehistoart.canalblog.com/archives/2012/05/05/24189517.html

The painted caves. In 1927, in the 'Theatre' chamber of Les Trois Freres, at Montsquieu-Avantes (Ariege), at the time of the discoveries. Seated: Abbé Breuil, and to the right: Leon Pales.

Photo: Pales (1962)

An engraving of a bison on a limestone pebble from Laugerie Basse. It may have been a preparatory sketch for a painting in one of the caves.

An engraving of a bison on a limestone pebble from Laugerie Basse. It may have been a preparatory sketch for a painting in one of the caves.

Note the way the hooves are pointed down, not in a naturalistic position. It may be that the sketch was made from 'life' - a bison kill.

Photo: Man before history by John Waechter

Head of a bison drawn with the fingers on the clay floor at Niaux, French Pyrenees. It lies over half a mile from the cave entrance. Dating from the Magdalenian period, it measures 24 inches (60 cm) in length.

Head of a bison drawn with the fingers on the clay floor at Niaux, French Pyrenees. It lies over half a mile from the cave entrance. Dating from the Magdalenian period, it measures 24 inches (60 cm) in length.

Photo: Man before history by John Waechter

Oiseaux stylisés de Malta (Sibérie). Collection Musée de l'Hermitage.

Oiseaux stylisés de Malta (Sibérie). Collection Musée de l'Hermitage.

Stylized birds of Malta (Siberia). Collection Musée de l'Hermitage.

Photo and French text: "les mammouths - Dossiers

Archéologie - n° 291 - Mars 2004"

My thanks to Anya for access to this resource.

Mammoth figurine no.1, bone, from New Avdeevo

Photo: M. Gvozdover, 'Art of the Mammoth Hunters'

Click on the image to see a close up

Click on the image to see a close upMammoth figurine no.2, sandstone, from New Avdeevo

Photo: M. Gvozdover, 'Art of the Mammoth Hunters'

Statuette de mammouth de Kostienki 1. Collection MAE. Photo L. Iakovleva.

Statuette de mammouth de Kostienki 1. Collection MAE. Photo L. Iakovleva.

Mammoth figurine from Kostienki 1. Collection MAE.

Photo and French text: "les mammouths - Dossiers

Archéologie - n° 291 - Mars 2004"

Photograph L Iakovleva.

My thanks to Anya for access to this resource.

Click on the image to see a close up

Click on the image to see a close upHorse figurine, mammoth ivory, from New Avdeevo

Photo: M. Gvozdover, 'Art of the Mammoth Hunters'

Drawing of two deer, incised on reindeer foot-bone. Found in 1833/1834 by a notary called André Brouillet in Chaffaud Cave, on his land in the hills between Poitiers and Angoulême, near Vienne, central-western France. Probably about 13 000 years old, Length 132 mm, height 37 mm.

Photo: © MAN

Os gravé figurant deux biches et deux poissons.

Engraved bone showing two does and two fish, from la grotte du Chaffaud à Savigné, Vienne, France.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Chamois, Grotte des Eyzies, fragment of rib, Magdalenian.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

Saiga antelope, le Peyrat, bone fragment, Magdalenian.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac

Pendeloques en os, les grottes de La Garenne à Saint-Marcel, Indre.

Pendants in bone from les grottes de La Garenne à Saint-Marcel, Indre.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Bone pendant from les grottes de La Garenne à Saint-Marcel, Indre, 16 000 BP - 18 000 BP.

A very interesting abstract design has been worked on this piece, another version of the central pendant in the image immediately above.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Bone pendant from les grottes de La Garenne à Saint-Marcel, Indre, 16 000 BP - 18 000 BP.

This shows an animal, possibly a feline, in full flight, completed in bas relief style.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Facsimile, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Plaquette de schiste gravée figurant un renne, les grottes de La Garenne à Saint-Marcel, Indre.

Plaque of schist, engraved with a running reindeer, from les grottes de La Garenne à Saint-Marcel, Indre.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Fish, Sole.

Contour découpé, Lespugue, Haute-Garonne.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Facsimile, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Pierced ivory beads, with the piercing having been broken out, 37 000 BP - 40 000 BP.

Lommersum, Nordrhein-Westfalen, about 20 km south west of Köhln.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source and text: Original, Monrepos Archäologisches Forschungszentrum und Museum, Neuwied, Germany

Three dimensional sculpture of a horse carved in ivory, with coat and markings shown by engraved shading, from the Grotte des Espelugues, Lourdes, Hautes Pyrenees. Length 7.5 cm. Discovered in 1886 in a crevice in the Grotte. Musee de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Three dimensional sculpture of a horse carved in ivory, with coat and markings shown by engraved shading, from the Grotte des Espelugues, Lourdes, Hautes Pyrenees. Length 7.5 cm. Discovered in 1886 in a crevice in the Grotte. Musee de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Photos: (top left) A. Sieveking 'The Cave Artists'

(top right) http://www.primtech.net/ivory/ivory.html

(bottom left) http://www.musee-antiquitesnationales.fr/pages/page_id18167_u1l2.htm

Three dimensional sculpture of a horse carved in ivory, with coat and markings shown by engraved shading, from the Grotte des Espelugues, Lourdes, Hautes Pyrenees. Length 7.5 cm. Discovered in 1886 in a crevice in the Grotte. Musee de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Photo: Nicolas Guerin, 2010.11.22

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution - Share Alike 3.0 Unported

(note that this appears to be a museum quality facsimile - Don )

The two sides of a decorated spatula from la grotte du Rey (Eyzies?), of deer antler. Note the chevrons or arrowheads on one side, and the line with separated marks at right angles on the other.

It may well represent a fish. See page 258 of: La spatule aux poissons de la grotte du Coucoulu à Calviac (Dordogne) André Leroi-Gourhan Gallia préhistoire Year 1971 Volume 14 Issue 14-2 pp. 253-259

Photo: http://www.arretetonchar.fr/

Mammoth in bas relief from la Grotte de Saint-Front-de-Domme.

Height 140 cm, Magdalenian.

Photo: http://www.arretetonchar.fr/

Fossil coral pendant, length 7 cm, from la Grotte de la Mairie, near Angoulême.

Photo: http://www.arretetonchar.fr/

Engraving of a fish, from Fontarnaud, Lugasson. Magdelanian, reindeer antler.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Catalog: 60.842.20

Source: Original, Musée d'Aquitaine à Bordeaux

Engraving of the head of a deer, from Fontarnaud, Lugasson.

Magdelanian, bone.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Catalog: 60.842.19

Source: Original, Musée d'Aquitaine à Bordeaux

Reindeer engraving, Limeuil

Label:

Renne gravé

Chez Bellanger (Abri Bellanger) Limeuil (Dordogne)

Calcaire

Inv. No 12022

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Reindeer engraving, Limeuil

Limeuil is a prehistoric site of Dordogne, France, at the junction of the Vézère and Dordogne rivers. It was occupied at the end of the Upper Palaeolithic and nearly 300 engraved limestone plates were uncovered there.

The archaeological layer was discovered accidentally during work at the bakery of Leo Bélanger. The Ministry of Culture of the time (Directorate of Fine Arts) commissioned Jean Bouyssonie a pre-historian of Brive, to excavate the area. These excavations, made difficult by the proximity of buildings, took place between 1909 and 1913.

The only encountered archaeological layer was attached to the Magdalenian VI on typological and stylistic bases.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Text: Wikipedia

Reindeer engraving, Limeuil

A 14C date published in 1989 gave an age of 11 720±120 years BP for reindeer antlers found in the deposit.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Text: Wikipedia

Engraving of a horse, Limeuil

Material: Limestone

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye

Engraving of what may be a deer.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Poster highlighting the outline of the engraving above.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Horse engraving from Longueroche.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, display at Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies

Baguettes (rods) engraved with horses on reindeer antler, probably by the same artist.

From Le Souci, Lalinde (Dordogne)

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Bâton percé with multiple holes.

Most spear straighteners have just the one hole. This artisan seems to have decided to make the equivalent of a swiss army knife, with a hole for every sized shaft!

From Le Souci, Lalinde (Dordogne)

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Engraving on a bear's canine tooth.

Note the pattern - a repetition of this pattern, mirrored, would make the hexagonal pattern seen on some other pieces, especially engravings on mammoth tusk.

Label:

Dent gravée

La Souquette, Sergeac (Dordogne)

Canine d'ours

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Original, Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Périgord, Périgueux

Decorated mammoth tusk, 19 000 BP

Kyiv, str. Cyril (now Frunze Str.).

Photo and text: http://www.nmiu.com.ua/en/expositions/prehistoric-period-in-ukraine.html

Madgdalenian horse head carved in bone - one of the most beautiful examples of prehistoric carving. Found in a cave excavation, its date is fixed to about 14 000 BP. The structure of the bone did not allow for carving in the round, and the reverse side is flat.

Photo: Man before history by John Waechter

Abri du Roc-aux-Sorciers, cave Taillebourg, Angles-sur-L'Anglin (Vienne). Tête de cheval en deux fragments.

Abri du Roc-aux-Sorciers, cave Taillebourg, Angles-sur-L'Anglin (Vienne, France). Head of a horse in two pieces.

Photo from: Agenda de la Préhistoire 2002 - 2003, a superb diary with excellent illustrations sent to me by Anya. My thanks as always.

Caverne de Niaux (Ariège)

Caverne de Niaux (Ariège)

Salon Noir, Cheval barbu

Black room, bearded horse

Photo from: Agenda de la Préhistoire 2002 - 2003, a superb diary with excellent illustrations sent to me by Anya. My thanks as always.

Caverne de Niaux (Ariège)

Caverne de Niaux (Ariège)

Successive paintings, one on top of the other

Photo from: Man before History by John Waechter

Caverne de Niaux (Ariège), galeries profondes. Empreintes de pieds

Caverne de Niaux (Ariège), galeries profondes. Empreintes de pieds

Caverne de Niaux, (Ariège), lower galleries. Footprints

Photo from: Agenda de la Préhistoire 2002 - 2003, a superb diary with excellent illustrations sent to me by Anya. My thanks as always.

Le Portel (Ariège), Cheval

Le Portel (Ariège), Cheval

Le Portel (Ariège), Horse

Photo from: Agenda de la Préhistoire 2002 - 2003, a superb diary with excellent illustrations sent to me by Anya. My thanks as always.

A dun pony near Silver City NM, as well as his dad and brother. Note the similar markings to the dun Devonshire pony above.

Photo: Jeff and Helena Hammer, near Silver City, New Mexico, USA.

These horses have been brought back from the edge of extinction, and there is a good website describing them at

http://www.spanish-mustang.org/startsms.htm

Helena Hammer writes: It may be that Darwin's dun pony was not so much a surviving individual of a vanished equine race, but more the result of what biologists call an atavism, a throwback to a primitive trait, in this case the original coloring of horses. As I understand it, this sometimes occurs when long isolated populations are reunited. Mules (ass x horse) are an excellent example. Something akin to their common ancestor's coat pattern, as well as other interesting physical attributes, can reemerge.

A little sister and a filly with good markings. Usually colts have better markings than fillies, but this one is exceptional.

Photo: Jeff and Helena Hammer, near Silver City, New Mexico, USA.

The following information comes from http://www.spanish-mustang.org/startsms.htm

Colour

Always regular dun or grulla (no red dun), typically a rather light shade. Face/muzzle dark, and dark around the eyes. A mealy mouth is not acceptable. Ears are outlined black in front and back, with whitish rim; tipped black on backside, sometimes also striped on backside. Fawn-colored tuft inside ear. Bi-colored mane and tail = the black middle part is fringed by light-colored, often almost white, hair. A dorsal stripe must be present; cobwebbing on forehead, zebra stripes on legs, neck stripes, shoulder stripes, and fishbone markings on the back are all desirable, although not always present. White markings are atypical and undesirable.

This is an excellent organisation of the drawing styles from some French and Spanish caves.

The columns left to right are of:

Signs, Bison, Aurochs, Horses, Ibex, Reindeer, Mammoths/Deer, Rhinoceros.

References

- Azéma, M. and Rivère, F., 2012: Animation in Palaeolithic art: a pre-echo of cinemaAntiquity, 2012; 86(332): 316–324

- Azéma, M., 2009: L'art des cavernes en action : Tome 1, Les animaux modèles : aspect, locomotion et comportement, Editeur : Editions Errance (7 novembre 2009)

- Bahn, P., 1998: The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art, Cambridge University Press , 1998.

- Breuil, H., 1979: Beyond the Bounds of History, Scenes from the Old Stone Age, Gawthorn, 1979, reprinted from the edition of 1949, London.

- Duhard, J., 1996: Réalisme de l'image masculine paléolithique, Editions Jérôme Millon , January 1, 1996

- Guthrie, D., 2005: The Nature of Paleolithic Art, University of Chicago Press

- Jaubert J., 2008: L'art pariétal gravettien en France: éléments pour un bilan chronologique, Paléo, 20 | 2008, 439-474.

- Pales L., 1962: L'abbé Breuil (1877-1961) Journal de la Société des Africanistes 1962, tome 32 fascicule 1. pp. 7-52.

- Veil S., Breest K., Grootes P., Nadeau M., Hüls M., 2012: A 14 000-year-old amber elk and the origins of northern European art Antiquity 86 (2012): 660–673

- Joordens J. et al., 2012: Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving, Nature Vol 518 12 February 2015

Altamira Cave is 270 metres long and consists of a series of twisting passages and chambers, and is decorated with ice age paintings. The artists used charcoal and ochre or haematite to create the images. They also exploited the natural contours in the cave walls to give their subjects a three-dimensional effect. The Polychrome Ceiling is the most impressive feature of the cave, depicting a herd of extinct Steppe Bison in different poses, two horses, a large doe, and possibly a wild boar. Around 13 000 years ago a rockfall sealed the cave's entrance, preserving its contents until its eventual discovery.

Altamira Cave is 270 metres long and consists of a series of twisting passages and chambers, and is decorated with ice age paintings. The artists used charcoal and ochre or haematite to create the images. They also exploited the natural contours in the cave walls to give their subjects a three-dimensional effect. The Polychrome Ceiling is the most impressive feature of the cave, depicting a herd of extinct Steppe Bison in different poses, two horses, a large doe, and possibly a wild boar. Around 13 000 years ago a rockfall sealed the cave's entrance, preserving its contents until its eventual discovery.

The cave of Mas-d'Azil is a large, 500 metre long tunnel dug by the Arize River through a wall of the Massif Plantaurelin, part of the Ariege Pyrenees. Secondary caves leading off the main tunnel were occupied at various prehistoric and historic times during a period of 20 000 years, and the objects found there gave the name of the cave to a prehistoric culture, the Azilian. It was excavated by Edouard Piette in the 19th century, who interpreted the halter-like marks on animal heads as being evidence of the domestication of reindeer and horses.

The cave of Mas-d'Azil is a large, 500 metre long tunnel dug by the Arize River through a wall of the Massif Plantaurelin, part of the Ariege Pyrenees. Secondary caves leading off the main tunnel were occupied at various prehistoric and historic times during a period of 20 000 years, and the objects found there gave the name of the cave to a prehistoric culture, the Azilian. It was excavated by Edouard Piette in the 19th century, who interpreted the halter-like marks on animal heads as being evidence of the domestication of reindeer and horses.

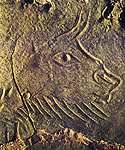

The Roc de Sers sculpted frieze is one of the relatively few examples of parietal art that can be confidently attributed to the Solutrean as it fragmented and fell off the rear wall of the rockshelter into dated archaeological deposits. Sculpture is rare in Upper Palaeolithic parietal art, and, given the relative paucity of Solutrean parietal art in general, Roc de Sers is doubly important as it serves as a benchmark for defining Solutrean artistic form and technique.

The Roc de Sers sculpted frieze is one of the relatively few examples of parietal art that can be confidently attributed to the Solutrean as it fragmented and fell off the rear wall of the rockshelter into dated archaeological deposits. Sculpture is rare in Upper Palaeolithic parietal art, and, given the relative paucity of Solutrean parietal art in general, Roc de Sers is doubly important as it serves as a benchmark for defining Solutrean artistic form and technique.