Back to Don's Maps

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Archaeological Sites

Back to Egypt Index Page

Back to Egypt Index Page

Ancient Egyptian Culture, Mummies, Statues, Burial Practices and Artefacts

The early beginnings of Ancient Egyptian culture to just before the First Dynasty.

In shape Egypt is like a lily with a crooked stem. A broad blossom terminates it at its upper end; a button of a bud projects from the stalk a little below the blossom, on the left-hand side. The broad blossom is the Delta, extending from the mouth of the Nile to Cairo, a direct distance of more than two hundred kilometres.

The bud is the Fayoum, a natural depression in the hills that shut in the Nile valley on the west, which has been rendered reliably cultivable for many thousands of years by the introduction into it of the Nile water, through a canal known as the 'Bahr Yussef'. Before this canal was dug, the Fayoum only filled at times of exceptionally high floods.

The long stalk of the lily is the Nile valley itself, which is a ravine scooped in the rocky soil for 1 100 km from the First Cataract to the apex of the Delta. The Nile's average discharge per day is 300 million cubic metres, and the Nile is usually 8 to 11 metres deep. After Aswan the width is averages 3 km. The widest part of the Nile is at Edfu, where it is 7.5 km wide, and the minimum width is at Silwa Gorge, near Aswan, where it is only 350 metres wide.

No other country in the world is so strangely shaped, so long compared to its width, so straggling, so hard to govern from a single centre. At the first glance, the country seems to divide itself into two strongly contrasted regions; and this was the original impression which it made upon its inhabitants. The natives from a very early time designated their land as 'the two lands,' and represented it by a hieroglyph in which the form used to express 'land' was doubled. The kings were called 'chiefs of the Two Lands,' and wore two crowns, as being kings of two countries.

These 'two Egypts' or 'two lands' were, of course, the blossom and the stalk, the broad tract upon the Mediterranean known as 'Lower Egypt' or 'the Delta' and the long narrow valley that lies, like a green snake, to the south, which bears the name of 'Upper Egypt'. Nothing is more striking than the contrast between these two regions.

Entering Egypt from the Mediterranean, or from Asia by the caravan route, the traveller sees stretching before them an apparently boundless plain, wholly unbroken by natural elevations, generally green with crops or with marshy plants, and canopied by a cloudless sky, which rests everywhere on a distant flat horizon. An absolute monotony surrounds the viewer. No alternation of plain and highland, meadow and forest, no slopes of hills, or hanging woods, or dells, or gorges, or cascades, or rushing streams, or babbling rills, meet their gaze on any side; look which way they will, all is sameness, one vast smooth expanse of rich alluvial soil, varying only in being cultivated or else allowed to lie fallow.

Turning their back with something of weariness on the dull uniformity of this featureless plain, the wayfarer proceeds southwards, and enters, at a distance of 200 km from the coast, on an entirely new scene. Instead of an illimitable prospect meeting him on every side, he finds himself in a comparatively narrow vale, up and down which the eye still commands an extensive view, but where the prospect on either side is blocked at the distance of a few miles by rocky ranges of hills, white or yellow or tawny, sometimes drawing so near as to threaten an obstruction of the river course, sometimes receding so far as to leave some miles of cultivable soil on either side of the stream. The rocky ranges, as he approaches them, have a stern and forbidding aspect.

They rise for the most part, abruptly in bare grandeur; on their craggy sides grows neither moss nor heather; no trees clothe their steep heights. They seem intended to keep in the inhabitants of the vale within their narrow limits, and bar them from any commerce or acquaintance with the regions beyond.

Photo: NASA

Permission: public domain

Text: Adapted from Rawlinson (1886)

Egypt before the humans came

While Europe experienced the last of the ice age, from 20 000 years ago to 10 000 years ago, Egypt (as a direct result of the ice age) experienced extremely arid conditions, and was largely uninhabited.

(left) Grosser Aletschgletscher, view from Eggishorn (2 927 m), in the background Jungfrau (4 158 m), Jungfraujoch (3 454 m), Mönch (4 099 m), Trugberg and Eiger (3 970 m)

(right) Sand dune near 'Areg, Siwa depression, Egypt

Photo (left): Dirk Beyer, permission: GFDL and cc-by-sa-2.5

Photo (right): Roland Ungerr, permission: GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version

During the latter part of the last ice age, between 20 000 and 10 000 years ago, the eastern Sahara was largely uninhabited, and extremely arid. During the final years of the ice age, intense winds blew across an extremely arid Sahara. Sand dunes stretched from central to northern Sudan. According to optical dates, from seventeen thousand to eleven thousand years ago (15 000 BC to 9 000 BC) the howling wind deposited sand in the region of the Selima Sand Sheet. Dunes formed at Nabta Playa, the Great Sand Sea, and Wadi Bakht in the Gilf Kebir. As a result, the environment changed drastically. River system were eradicated and the wind scoured out hollows in the land. However, at the end of the ice age, archaeological and geological evidence suggests wetter conditions began to prevail.

As the climate grew more humid around 8 000 BC, rainfall turned low-lying areas into lakes and playas. With the onset of this 'Neolithic pluvial', the region we now know as Egypt became an extension of the Sahelian savanna. The area offered pastoralists and animals new habitable lands. The area received a minimum of 280 mm (11 inches) of rain per year, and possibly as much as 610 mm (24 inches). Between 7 000 BC and 4 000 BC, when the leading edge of monsoon rains covered a significant portion of Africa's interior, a 'pluvial maximum' - when rainfall was at its peak - developed, turning the desert green with life.

Some records indicate that the onset of rains began at Bir Kiseiba around 10 000 BC, but in many other areas, including Abu Ballas in south-central Egypt, they came a thousand years later. Nonetheless, by 7 500 BC, rising water tables were able to support lakes in the Sudan. The Nile-fed lake of Birket Qarun rose during this period, and in southern Egypt basins filled with rainwater. Radiocarbon dated charcoal from prehistoric campfires attests to the increasing humidity and cooling temperatures.

By 7 300 BC, the Wadi Howar was active in northern Sudan and flowed into the Nile River. Near Gebel Rahib, conditions sustained cool, freshwater lakes with a depth of twelve to thirty feet. Nabta Playa also experienced a wet climate before 7 400 BC. Mud accumulated along the Wadi Tushka and at other locations in the Great Sand Sea south of Siwa. By 7 100 BC, springs and artesian lakes existed in Kharga and Dahkla.

Text above: Malkowski (2010)

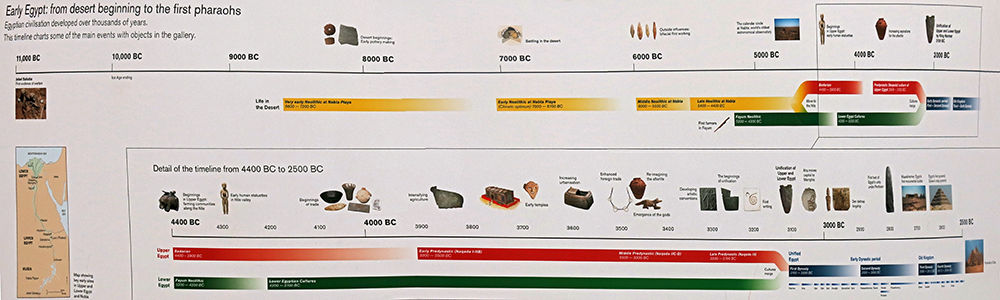

Egyptian Chronology

| Egyptian Chronology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date | Culture | Duration |

| 11 000 BC | Jebel Sahaba | |

| Before 8 000 BC - Palaeolithic in Europe and Northern Asia | ||

| 8 000 BC - Nominal end of the Ice Age | ||

| 8 600 - 4 400 BC | Nabta Playa Neolithic | 4 200 years |

| 6 100 - 5 180 BC | Qarunian (formerly known as Fayum B) | 920 years |

| 5 200 - 4 200 BC | Fayum A | 1 000 years |

| 4 800 - 4 200 BC | Merimde | 600 years |

| 4 600 - 4 400 BC | El Omari | 200 years |

| 4 400 - 4 000 BC | Badarian | 400 years |

| 4 000 - 3 300 BC | Maadi | 700 years |

| 3 900 - 3 650 BC | Naqada I | 250 years |

| 3 650 - 3 300 BC | Naqada II | 350 years |

| 3 300 - 2 900 BC | Naqada III | 400 years |

| 3 100 - 2 670 BC | Early Dynastic | 430 years |

| 2 670 - 2 181 BC | Old Kingdom | 489 years |

| 2 181 - 2 025 BC | First Intermediate Period | 156 years |

| 2 025 - 1 700 BC | Middle Kingdom | 325 years |

| 1 700 - 1 550 BC | Second Intermediate Period | 150 years |

| 1 550 - 1 077 BC | New Kingdom | 473 years |

| 1 077 - 664 BC | Third Intermediate Period | 413 years |

| 664 - 332 BC | Late Period | 332 years |

| 525 - 404 BC | First Persian Period | 121 years |

| 404 - 343 BC | Late Dynastic Period | 61 years |

| 343 - 332 BC | Second Persian Period | 11 years |

| 332 - 305 BC | Macedonian Period | 27 years |

| 305 - 30 BC | Ptolemaic Period | 275 years |

| 30 BC - 395 AD | Roman Period | 425 years |

| 395 AD - 640 AD | Byzantine Period | 245 years |

| 640 AD - 1517 AD | Islamic Period | 877 years |

| 1517 AD - 1867 AD | Ottoman Period (French Occupation 1798-1801) |

350 years |

| 1867 AD - 1914 AD | Khedival Period | 47 years |

| 1914 AD - 1922 AD | Sultanate under Hussein Kamel, as a British Protectorate |

8 years |

| 1922 AD - 1953 AD | Monarchy | 31 years |

| 1953 AD - Present Day | Republic | |

The vast majority of Predynastic archaeological finds have been in Upper Egypt, because the silt of the Nile River was more heavily deposited at the Delta region, completely burying most Delta sites long before modern times.Text above: Wikipedia

1 400 000 BC - 200 000 BC

Faustkeil, Handaxe

This hand axe is of Acheulian culture, and is the oldest piece in the August Kestner Museum in Hannover.

( It appears to be of a material similar to silcrete, and is a coarse grained example with bedding lines and inclusions, only suitable for crudely made large tools such as this handaxe or chopping tool. - Don )

Catalog: Eastern Sahara / Bayuda desert in present day Sudan

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source and text: Original, Museum August Kestner, Hannover

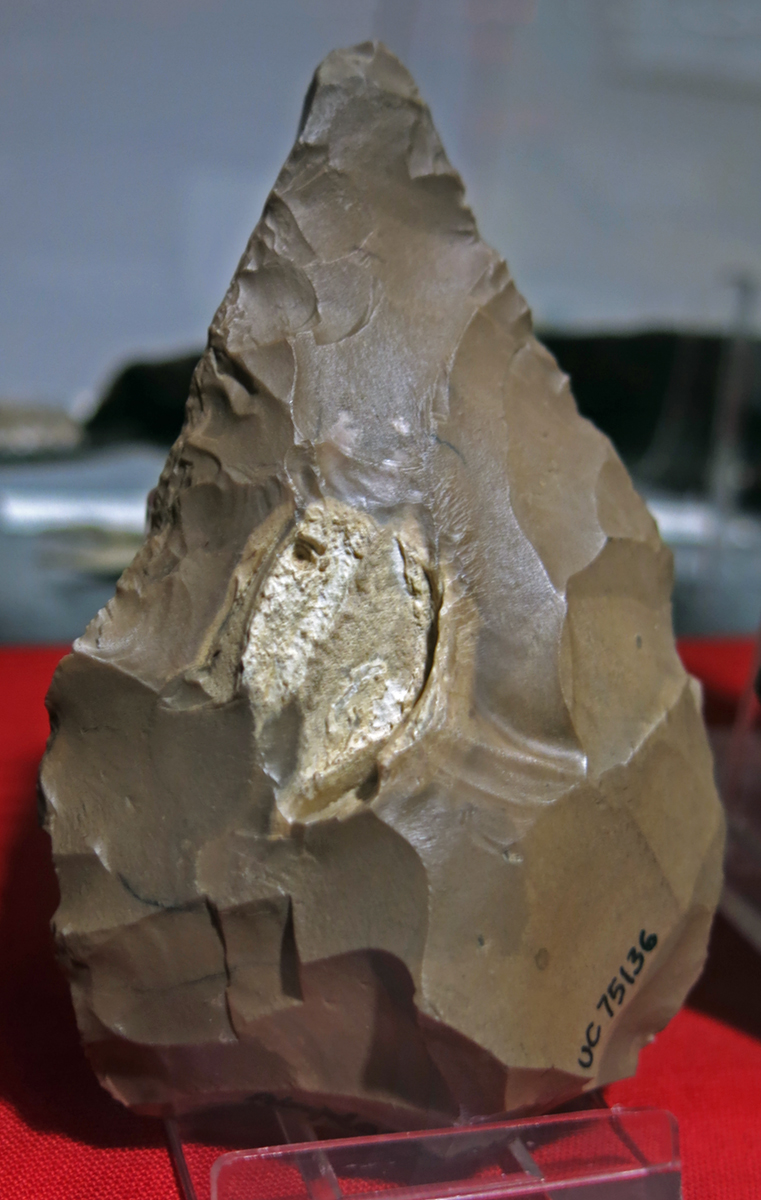

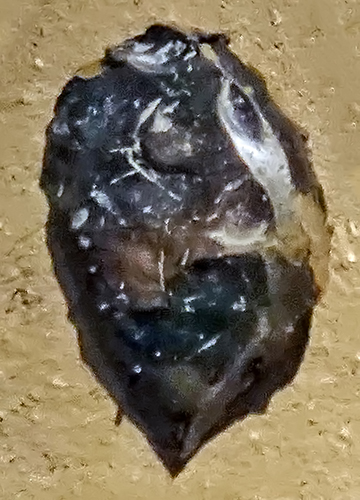

Retouched flint flake, handaxe?, Abydos

Age 400 000 BP - 350 000 BP.

Length 98 mm, width 63 mm.

Accession Number LDUCE-UC75136

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Petrie Museum, London, England

Text: Card / online catalogue, the Petrie Museum, © 2015 UCL. CC BY-NC-SA license.

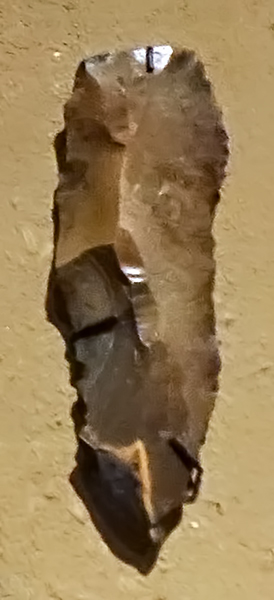

Flint handaxe, Acheulean; with cortex butt. From El Amrah, Nile level.

Age 400 000 BP - 350 000 BP.

Length: 135 mm

Accession Number LDUCE-UC13575

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Petrie Museum, London, England

Text: Card / online catalogue, the Petrie Museum, © 2015 UCL. CC BY-NC-SA license.

Acheulian Handaxe

(Acheulian - Old Palaeolithic : about 1800 000 BC - 200 000 BC; typical are large bifacially flaked handaxes, picks and cleavers; people lived as gatherers of wild plants and scavengers/hunters of animals)

Age of this specimen 400 000 BP - 350 000 BP.

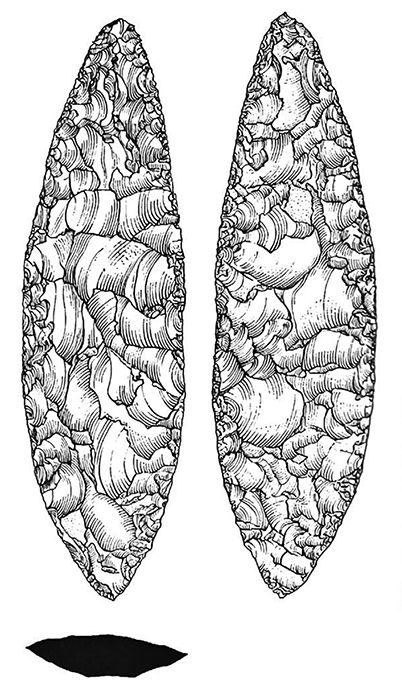

Flint handaxe, developed Acheulean, with cortex butt. Found 9 miles NNW of Naqada at 1400 ft above sea-level, on a hill-top plateau.

Lanceolate bifaces like this one are the most aesthetically pleasing and became the typical image of developed Acheulean bifaces. Their name is due to their similar shape to the blade of a lance. Bordes defined a lanceolate biface as elongated (l/m > 1.6 , i.e. maximum length / maximum width > 1.6) with rectilinear or slightly convex edges, acute apex and rounded base, 2.75 < l/a < 3.75. L/a is maximum length / distance from point of maximum width to base and expresses the position of maximum width in relation to the length.

They are often globular to the extent that it is not a flat surface, at least in its basal zone, with m/e < 2.35 , m/e meaning the ratio of maximum width / maximum thickness and expresses the thickness relative to width, or 'refinement' of the axe.

They are usually balanced and well finished, with straightened edges. They are highly characteristic of the latter stages of the Acheulean – or the Micoquian, as it is known – and of the Mousterian in the Acheulean Tradition (closely related to the Micoquian bifaces).

Length 174 mm

Accession Number LDUCE-UC13577

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Petrie Museum, London, England

Text: Card / online catalogue, the Petrie Museum, © 2015 UCL. CC BY-NC-SA license.

Flint handaxe, developed Acheulean, with cortex butt one side.

Lanceolate bifaces like this one are the most aesthetically pleasing and became the typical image of developed Acheulean bifaces. Their name is due to their similar shape to the blade of a lance. Bordes defined a lanceolate biface as elongated (l/m > 1.6 , i.e. maximum length / maximum width > 1.6) with rectilinear or slightly convex edges, acute apex and rounded base, 2.75 < l/a < 3.75. L/a is maximum length / distance from point of maximum width to base and expresses the position of maximum width in relation to the length.

They are often globular to the extent that it is not a flat surface, at least in its basal zone, with m/e < 2.35 , m/e meaning the ratio of maximum width / maximum thickness and expresses the thickness relative to width, or 'refinement' of the axe.

They are usually balanced and well finished, with straightened edges. They are highly characteristic of the latter stages of the Acheulean – or the Micoquian, as it is known – and of the Mousterian in the Acheulean Tradition (closely related to the Micoquian bifaces).

Found by Seton-Karr at a low level at al-Ga'ara SE of Dendera.

Length 151 mm, Accession Number LDUCE-UC13579.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Petrie Museum, London, England

Text: Card / online catalogue, the Petrie Museum, © 2015 UCL. CC BY-NC-SA license.

Additional text: Wikipedia, ikarusbooks.co.uk/resources/Lsarc.pdf

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Faustkeile, Handaxes

Left: from the Bissing collection.

Catalog: Flint, Thebes, ÄS 1211, ÄS 1489

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

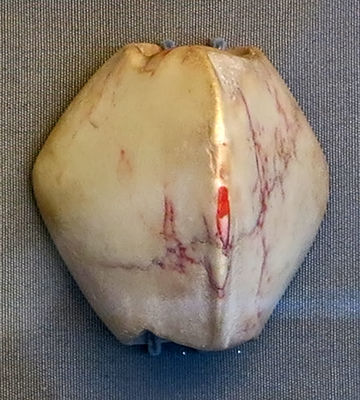

Tortoise core.

A tortoise core is a style of core typical of flintworking in the Levallois technique where the aim is to produce large oval flakes with a sharp edge all round. This results in a core that has one flattish face and a low domed back that, overall, resembles a tortoise.

Unstained flint tortoise core: Thebes, found on surface of gravel, 'Wadi Mermus', Thebes. From the C.G. Seligman Collection.

Length 120 mm, Accession Number LDUCE-UC13543

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Petrie Museum, London, England

Text: Card / online catalogue, the Petrie Museum, © 2015 UCL. CC BY-NC-SA license.

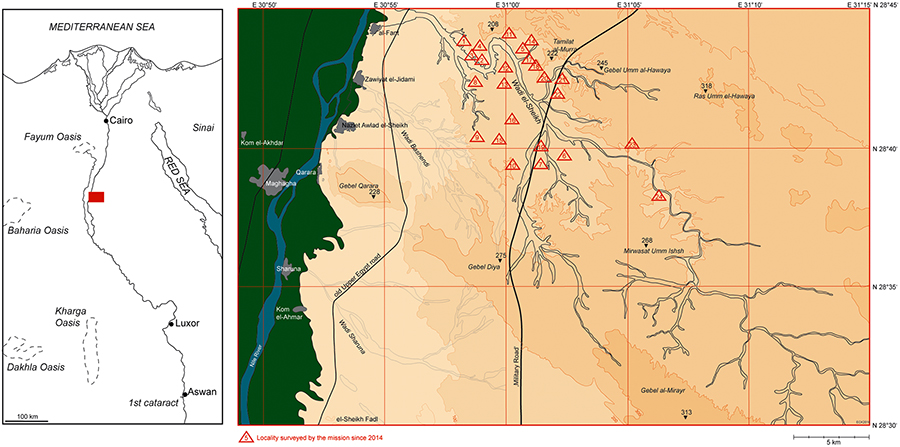

Map of Egypt and of Wadi el-Sheikh, a major source of flint for Egypt since Palaeolithic times.

The red rectangle on the left shows the location of Wadi el-Sheikh in Middle Egypt. The map on the right shows Wadi el-Sheikh and its surroundings; red triangles indicate localities surveyed by the University of Vienna Middle Egypt Project until 2015.

Wadi el-Sheikh in Egypt is a major source for the acquisition of chert, often also referred to as flint or silex. This is the raw material used primarily for the manufacture of tools and implements during the prehistoric and Pharaonic periods at least until the end of the 2nd Millennium BC, i.e. over many thousands of years, before metal fully replaced stone on a larger scale. Wadi el-Sheikh was first discovered by the British officer-cum-adventurer Haywood W. Seton-Karr in 1896 who conducted two expeditions and subsequently distributed his numerous surface finds to museum collections world-wide. He already recognised the importance of this discovery for ancient chert mining.

A few archaeologists have visited and briefly surveyed the Wadi in the following century; each time, they essentially concurred with Seton-Karr on the significance of this area, but no systematic archaeological investigation has ever taken place. Also, those few who did visit the Wadi engaged in relatively superficial examinations of limited areas. While being valuable studies in their own right, such research has only ever provided a snap shot of activities that have taken place there and have not done justice to the size and complexity of this area as a whole.

This changed recently when the University of Vienna Middle Egypt Project set out to survey substantial portions, excavate select areas and to design a long-term research project for the Wadi with the aim to scientifically investigate this area using a thorough and systematic approach. This article covers fieldwork conducted over three brief seasons of different research activities during 2014 and 2015. As a result of this recent research, it is now possible to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the archaeological evidence and to demonstrate its great potential for archaeological research on ancient Egyptian resource acquisition, economy and lithic technology.

Photo: E. C. Köhler

Source and text: University of Vienna Middle Egypt Project, Köhler et al. (2017)

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Faustkeile, Handaxes

(left) Catalog: Flint, Wadi el-Sheikh, collection of Seton-Karr, ÄS 1219

(centre) Catalog: Flint, Thebes, ÄS 1494

(right) Catalog: Flint, Thebes, ÄS 1453

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Schaber, scraper

Scrapers are used to scrape off meat and fat on skins and to work on wood and bone. The earliest examples are made similarly to handaxes, but have a longer edge compared to the grip.

( This appears to be a sidescraper. The scraping surface is on the left, the grip or handle is on the right. Sidescrapers are the norm for early scrapers. Later, with blade technology, the scraper (grattoir), was on one or both ends of a long blade, a much better design, since it uses less flint, has more leverage, is very much faster to knap, and is suitable for both coarse and fine work - Don )

Catalog: Flint, Thebes, ÄS 1490

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

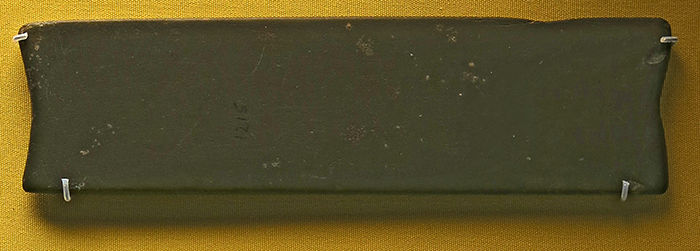

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Bohrer, drill

Early drills look very similar to handaxes, but have a long sharp tip.

( This flint appears to be of exceptionally fine quality - Don )

Catalog: Flint, Thebes, ÄS 1491

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

15 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Schaber, scraper

( This scraper has been made on a blade, and is very long for its width. It is probably a Mesolithic example, circa 15 000 BC or later, when the technology had improved greatly. The scraping surface is on the right, the grip or handle is on the left. It appears to have been made from a flake, rather than directly from the reduction of a core. The scraping edge on the right has been carefully retouched.

Some scrapers, such as this one, are designed with convex, concave, and straight sections of the edge for different tasks with the same tool - Don )

Catalog: Flint, Thebes, ÄS 1491

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

15 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Messer, knives

In the course of time, the shape of the blades became more and more specialised. Mesolithic knives are long, with a straight edge and a rounded back so that they fit better in the hand. The knives of this period do not yet have an additional handle of wood, bone, leather or antler.

( These 'backed' knives were designed to be held in the hand, with the index finger pushing on the blunted back of the knife during use - Don )

Catalog: Flint, Wadi el-Sheikh, collection of Seton-Karr, ÄS 1015, ÄS 1228, ÄS 1227, ÄS 1877

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Axtklinge, axe head

Axe blades of this shape were shafted in wooden handles. In Egypt, stone axes have been found in the Palaeolithic, disappear in the course of the Mesolithic and reappear in the Neolithic. They are also documented in the Early Period, after which they are gradually replaced by metal axe blades.

Catalog: Flint, Wadi el-Sheikh, collection of Seton-Karr, ÄS 1221

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

Axtklingen, axe heads

These small axe blades were probably used for woodworking rather than for felling trees.

( These examples may well have been used transversely, as adzes, which are very useful woodworking tools.

Note also that the axeblade on the right has had its working edge smooth and sharp - Don )

Catalog: Flint, Wadi el-Sheikh, collection of Seton-Karr, ÄS 1427, ÄS 1428

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

70 000 BC - 7 000 BC

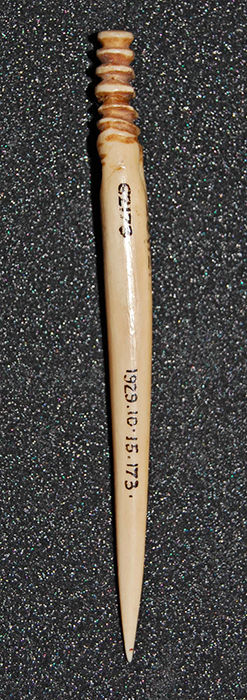

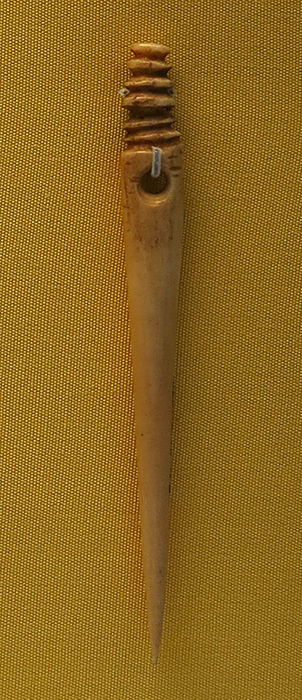

Ahlen, awls

These long blades with a thin point were used to pierce holes in thin material such as fur.

Catalog: Flint, Wadi el-Sheikh, collection of Seton-Karr, ÄS 1222, ÄS 1224, ÄS 1225

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, Ägyptischen Museum München

Text: Museum card, © Ägyptischen Museum München

Palaeolithic: 50 000 BC - 3 000 BC

Stone Age Tools

1 - Hunter-gatherers of the Palaeolithic

(bottom left) At first, the desert was still a fertile savannah. On the mountain slopes behind Thebes there are thousands of tools of the hunters who lived there at that time.

The tools shown are of lint, from Thebes, and are of the Mousterian culture.

Circa 50 000 BC - 30 000 BC

2 - Hunter-gatherers of the Sebilian culture.

(bottom right) Small flints serve as arrowheads, harpoons, or scrapers.

Flint, near Kom Ombo (Sebilian) circa 12 000 BC - 10 000 BC.

The culture is known by the name given by Edmond Vignard to finds he located at Kom Ombo on the banks of the river Nile from 1919 continuing into the 1920s.

Nine sites were found by A. Marks in the area of the Wadi Halfa; Wendorf located three approximately 10 kilometres from Abu Simbel. The culture is located in its entirety only in proximity to the Nile, ranging from Wadi Halfa to Qena.

3 - Farmers and fishermen in the Fayum

(top left) Characteristic are the arrowheads with hollow bases.

The arrowheads are made of flint, circa 5 000 BC - 4 000 BC.

(Fayum-culture)

4 - A city of farmers

(top right) Maadi (12 km upstream from modern Cairo) was already a real city with hundreds of houses and an extensive cemetery.

The tools are of flint, circa 4 000 BC - 3 000 BC.

(Maadi culture)

Cartographer: Unknown

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Poster, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

Jebel Sahaba: A violent death

Life was difficult around 11 000 BC. Glaciers over Europe made the Nile Valley cold and dry, while the river was high and wild. Resources must have been scarce. Competition for food may explain why in one cemetery near Jebel Sahaba (northern Sudan) 45% of the men, women and children died of inflicted wounds. Remnants of stone weapons, and cut marks on the bones, provide the earliest evidence in history for large scale violent conflict.

Text above: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

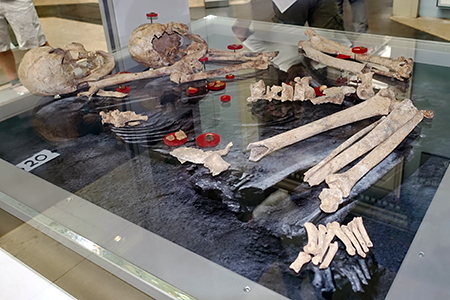

Photograph of Burials 20 and 21 when excavated in 1964.

The pencils point to the location of stone chips.

Photo and text: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

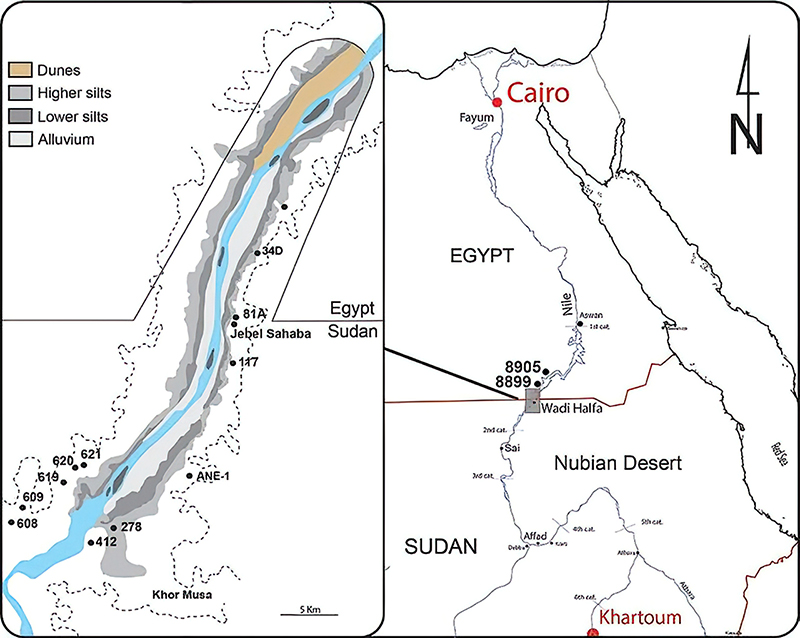

Location of Jebel Sahaba, now submerged in Lake Nasser.

Photo: Drawn by D. Usai

Source: Usai (2020)

Burials 20 and 21 at Cemetery 117

Two of the victims are shown as they were buried with weapon fragments in position (on red discs). Both were adult men.

Catalog: Jebel Sahaba 117, Epi-Palaeolithic, EA77840, EA77841, EA81433 - EA81449, EA82050 - EA82055

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Burials 20 and 21 at Cemetery 117

Cuts on the legs of one skeleton (see red triangular pointers) were probably made by arrows shot at high velocity. The other man had six chert fragments in his abdomen, lower arms and one in his neck.

Catalog: Jebel Sahaba 117, Epi-Palaeolithic, EA77840, EA77841, EA81433 - EA81449, EA82050 - EA82055

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Burials 20 and 21 at Cemetery 117

Clusters of stone chips found within one skeleton give evidence of wounds to his chest, legs, arms and head. Several more chips are also embedded in his bones.

Catalog: Jebel Sahaba 117, Epi-Palaeolithic, EA77840, EA77841, EA81433 - EA81449, EA82050 - EA82055

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

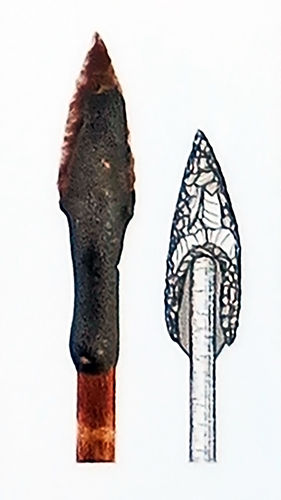

Weapons used at Jebel Sahaba

These stone pieces are some of the larger remnants of the weapons found at Jebel Sahaba graves. Most were small flakes of chert called microliths that were originally assembled together on wooden shafts to make arrows or other weapons.

Tools constructed in this way were used by the hunter-gatherer cultures across North Africa and Europe during the late Palaeolothic. Clusters of stone chips found in the Jebel Sahaba bodies probably derive from weapons fitted with several microliths. Some shattered on impact with the bones, or detached from the shaft. Either way, they remained in the soft tissue when the arrow was removed.

( which would have meant that even if the person injured by an arrow or spear survived the initial thrust, they would have succumbed to the resulting trauma later. No tissue around the microliths could heal and in the body’s attempt to rid itself of the foreign object the body's defence forces would rage forming an abscess. Every time the victim moved the microlith's rough edges would inflame and aggravate the injury and eventually lead to a fatal infection - Don )

Catalog: Jebel Sahaba 14, 29, 31, Epi-Palaeolithic, EA87057ab, EA82063a, EA82064ad, EA82288

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Additional text: https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/05/battle-wounds-never-pull-an-arrow-out-of-a-body/

Bone harpoon, replica, from the Mesolithic, 10 800 - 7 000 years ago.

This harpoon is a fine example of the use of microliths. Their use was not because of a lack of good flint, but because they were far more effective at dropping prey, owing to the shock they provided from the wound they made. The wound was large and lacerated, and the blood loss and associated organ damage disabled even large prey.

Although this was labelled as a harpoon, points of similar construction were used fixed to spear/arrow shafts.

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2014

Source: Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden.

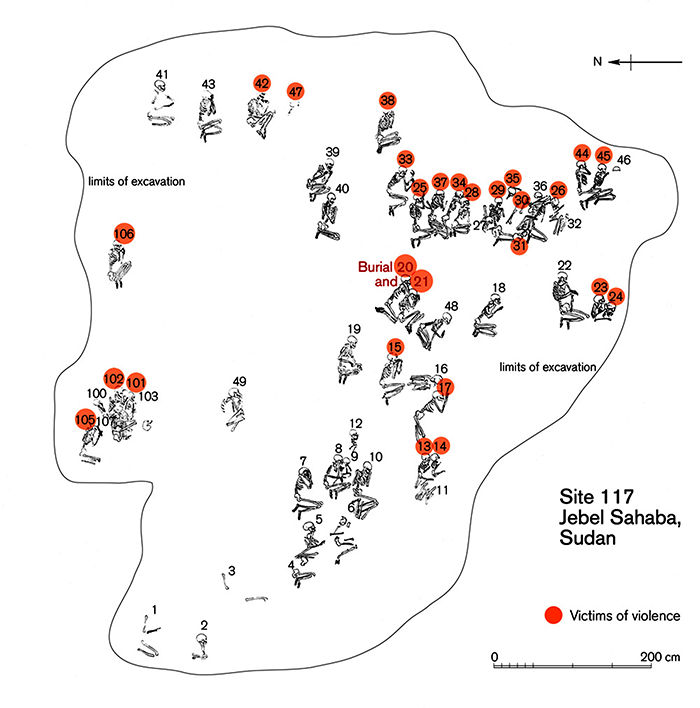

Map of Cemetery 117 at Jebel Sahaba

The burials with evidence for violence are highlighted in red. A violent death is indicated by the presence in the graves of stone chips and flakes, which are the remnants of composite weapons, and cut marks on the bones, made by arrows or knives. The victims displayed here were buried near the centre of the cemetery.

At least 61 individuals, comprising men, women and children, were buried at Jebel Sahaba. Some were buried alone, some in groups. All were placed in shallow graves capped with sandstone slabs. The bodies were interred in a tightly flexed position, lying on their left side, their heads to the south, facing east. No grave goods were put in the graves, but the standard position of the bodies indicates belief in an afterlife. Over time the site was used, probably by one tribe or extended family, as the designated place for burial. This makes it one of the earliest cemeteries in the world.

Photo: https://blog.britishmuseum.org/tag/jebel-sahaba/ © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Text: Card at the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Violence at Jebel Sahaba

Raids and skirmishes must have been common in the period of climate change around 11 000 BC. Conflict was brutal; not even women and children were spared. Healed injuries on some of the bones are the result of earlier violent encounters.

These bones are from the forearms (ulnae) of two different individuals. The top ulna has a fully healed fracture, in contrast to the normal ulna below it. This type of injury is called a parry fracture. It typically occurs when the arm is lifted to protect the head and deflect a powerful blow.

The fractured ulna is from a female, age 50+, stature 1610 ± 34 mm. The lower ulna is from the male whose mandible is shown below.

Catalog: Jebel Sahaba 31 and 26, Epi-Palaeolithic, EA77846, EA77850

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The people of Jebel Sahaba

People at Jebel Sahaba were very well-built and robust. Despite the violence they endured, many lived into adulthood, with some surviving beyond 50 years of age. They hunted, fished and collected wild plants for food.

The coarse diet wore away their teeth, as shown in this lower jaw (mandible) belonging to an older man. Once the crowns had worn down, the pulp was exposed to bacteria. This led to infections, creating abscesses. The large holes below the first molars are examples of dental abscesses. These must have caused the man severe discomfort.

Human skeletal remains. Male, age 50+ years; stature 1723 +/-39 mm (R femur). The skull was exceptionally preserved except for a damaged right temporal. Dentition-permanent 30. Dental disease: Heavy dental wear, tooth 23 crowded lingually by 22 and 24; abscess at 3, 12, 19, 22 and 30.

Trauma: Exostosis on right femur (3rd trochanter) with healed wound on central shaft. Fracture right elbow? Healed cut fracture on head of left MC1; ridge of bone on left talar articular facet due to impaction injury that is not completely healed. Osteoarthritis: Right elbow; distal articular surface of left fibula; osteophytosis and collapse of at least 3 of cervical vertebrae (Anderson 1968: 997 states '4 vertebrae'). Cutmarks: Healed cutmark on midshaft of right humerus; cutmark on anterior left iliac blade.

Catalog: Jebel Sahaba 31, Epi-Palaeolithic, EA77850

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/, © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

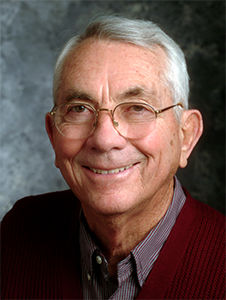

Fred Wendorf examining burials at Jebel Sahaba in 1965.

The discovery of Jebel Sahaba Cemetery 117 at Jebel Sahaba is a significant discovery for two reasons: it is one of the oldest formal burial grounds in the world, and it contained the earliest known evidence for inter-communal violence. Dr Fred Wendorf carried out systematic excavations here in 1965 as part of his mission to rescue early sites due to be flooded because of the Aswan High Dam. In 2002 Dr Wendorf donated his scientific collections and archives to the British Museum. This material is a unique resource for understanding the early inhabitants of the Nile valley and how they dealt with environmental change.

Photo and text: Poster, British Museum, Wendorf Archive (British Museum), © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

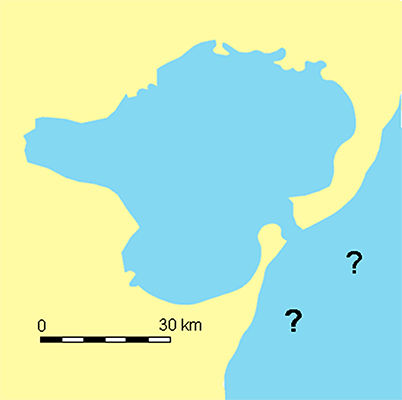

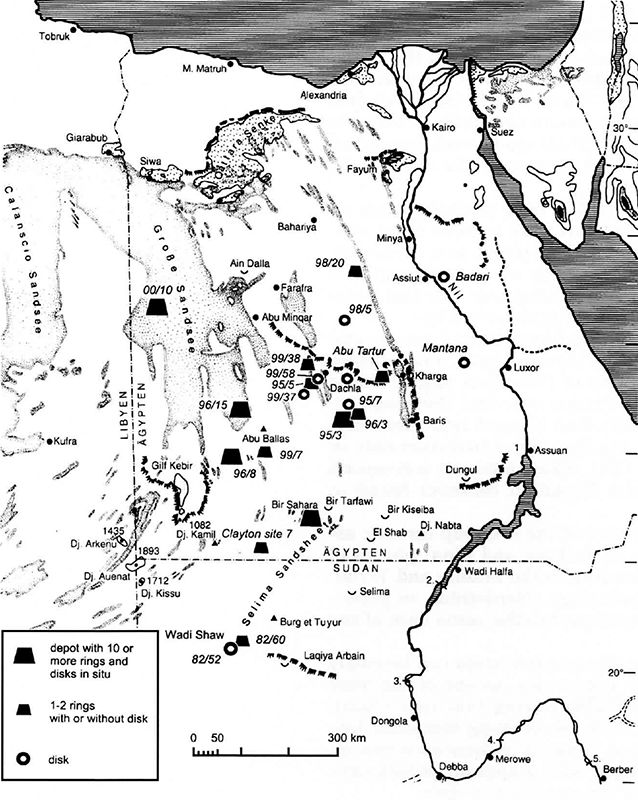

When the desert was green

8600-4400 BC

Today the Sahara is one of the driest places on earth, but it was not always that way. The end of the last ice age (about 10 000 BC) released moisture into the atmosphere and summer rain fell on the desert. Seasonal lakes (playas) formed, supporting enough grass and scrubland to make life possible during the summer months.

Gradually the climate turned dry and by 4400 BC people began to abandon the desert to settle in oases and by the river. There, they took up farming, an innovation from the Levant, triggering social and technological developments that led directly to the beginning of Egyptian civilisation at about 3100 BC. Nabta Playa, in southern Egypt, shown on the map at left, was one of the largest of these playa lakes.

Excavations by Dr Fred Wendorf and the Combined Prehistoric Expedition revealed that nomadic people lived by its shores sporadically for over 4000 years. In 2002 Dr Wendorf donated excavated material to the British Museum. This enables us to glimpse the lives of these early desert dwellers and learn how they coped with the precarious environment.

Photo: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

Text: poster at the Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

A portrait of Fred Wendorf, left, and Fred Wendorf at Nabta Playa.

In the early 1960s, archaeological monuments in Lower Nubia were threatened with obliteration from construction of the Aswan High Dam in the Nile River Valley of Egypt.

UNESCO launched an international salvage operation in an effort to save the region’s rich archaeological heritage.

In response to the UNESCO appeal, in 1962 Wendorf invited teams of scientists from Great Britain, France, Belgium, Poland and Egypt to participate in the rescue of the Nubian prehistoric monuments that would disappear under the waters of Lake Nasser with the completion of the new dam. This multinational research body became the Combined Prehistoric Expedition, which Wendorf directed until 1999, along with his collaborator Romuald Schild, professor at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology at the Polish Academy of Sciences (whom Wendorf affectionately referred to as his 'brother').

The Nubian Campaign made possible the discovery and rescue of hundreds of prehistoric sites along the Nile in the stretch extending on both sides of the river between Tushka in Upper Egypt to the southern end of the Second Cataract in Sudan. The Expedition has continued to carry out researches in Upper and Lower Egypt, the Western Desert of Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Sinai.

'The Combined Prehistoric Expedition, under Fred Wendorf’s direction, became the most enduring prehistoric expedition in the history of African archaeology, covering in its field work and subsequent publications almost the entire chronological expanse of prehistory from the Early Stone Age to the late predynastic and Bronze Age times', said Schild. 'The work of the Expedition over the past half century has provided comprehension as never before of human settlement, beliefs, social interaction and adaptation to the natural environments along the main Nile Valley, the deserts of eastern Sahara and Sinai, as well as the rift valleys of Ethiopia.'

Fred Wendorf died on the 15th of July 2015.

Photo: https://www.smu.edu/News/2015/fred-wendorf-dies-15july2015

Source and text: https://www.smu.edu/News/2015/fred-wendorf-dies-15july2015

Nabta PlayaText above: Wikipedia

Archaeological discoveries reveal that these prehistoric peoples led livelihoods seemingly at a higher level of organisation than their contemporaries who lived closer to the Nile Valley. The people of Nabta Playa had above-ground and below-ground stone construction, villages designed in pre-planned arrangements, and deep wells that held water throughout the year.

Findings also indicate that the region was occupied only seasonally, most likely only in the summer period, when the local lake filled with water for grazing cattle. Comparative research indicated that the indigenous inhabitants may have a significantly more advanced knowledge of astronomy and mathematics than previously thought possible.

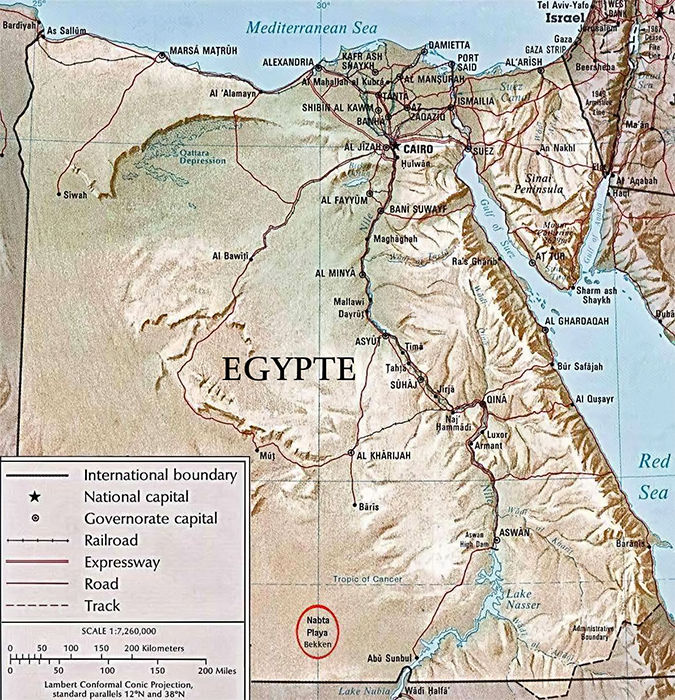

Map of Egypt with the approximate location of Nabta Playa circled near the bottom.

Photo: Dutch version of Public Domain Map, permission granted here, by the University of Texas at Austin.

Source: Map from The University of Texas at Austin: Egypt: Country Map.

Map reduced in size, and "Legend" and "Scale" moved up, to conserve space. Also approximate position of Nabta Playa noted: Latitude 22° 32' 00" North; Longitude 30° 42' 00" East.

Subsequently translated to Dutch from the aforementioned source from English Wikipedia.

Permission: Public Domain

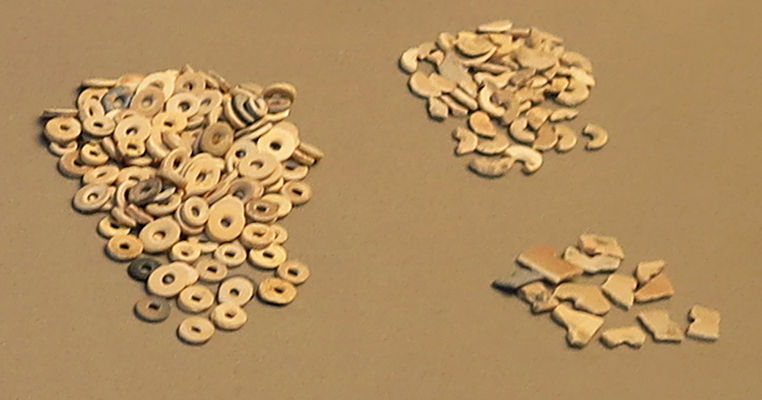

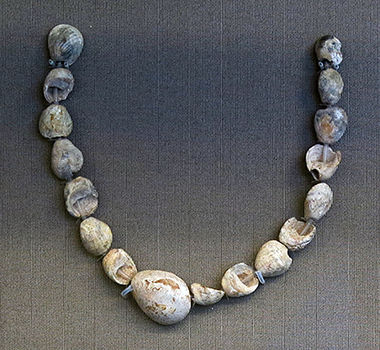

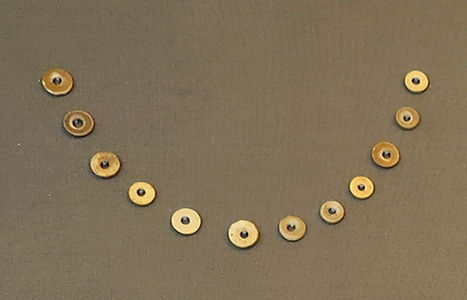

Ostrich eggshell beads, 8 000 BC - 6 750 BC

Making beads out of ostrich eggshell was one of the favourite pastimes of the inhabitants of Nabta Playa. All steps in the process have been preserved, along with the tools that were used to form and finish them.

Catalog: Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA81426

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Bead making: Step 1 (left)

First, the eggshells were collected, probably from abandoned nests, and roughly broken down to a usable size.

Bead making: Step 2 (right)

The edges of the eggshell fragments were then rounded by careful chipping, probably with a stone cobble.

Catalog: Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA81431, Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA81428

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Flint tools were used as awls for the next step, the drilling of the holes.

Catalog: Nabta E75-6, Early Neolithic, EA82307 - EA82311

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Bead making: Step 3

Next, a hole was drilled with one of the specially prepared flint perforators displayed above. These were probably mounted on a stick and rotated between the palms of the hand to make the hole in the centre of the eggshell disk.

Catalog: Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA81429

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Bead making: Step 4

In the final step, the edges of the bead were smoothed and polished by rubbing against a block of fine sandstone.

Drilling was the most difficult part of the operation, and many beads broke at this point, as shown on the upper right of this photo. An innovation of the Middle Neolithic period was to drill the hole first, and shape the bead later, saving time and effort, as shown on the lower right of this photo.

Catalog: Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA81426, Nabta E79-8, Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA81432, Nabta E79-8, Middle Neolithic, EA81427

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The smoothing and polishing action wore away the stone and produced grooves as seen in these polishers.

Catalog: Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA82294-5

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

(front) Ostrich egg. The ostrich lays the largest egg in nature. The shells of these eggs were important materials for the early nomadic people living in the desert. Complete egg shells were used as containers for water or other liquids and some were etched with intricate designs. They were probably carried in slings of leather or rope. Eggshell fragments were also shaped into beads and tools.

Catalog: EA22554

(back) Decorated basket. This oval basket was found within a silo. It is one of the oldest preserved baskets from Egypt. The vertical stripes woven into the sides were originally dark red. From the pattern we gain a rare glimpse into the artistic world of the Fayum dwellers not seen in their drab pottery.

Catalog: Fayum Kom K, Silo 55, Fayum Neolithic, EA58696

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

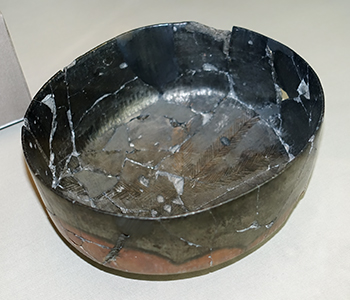

Pottery in the Fayum was purely functional. In contrast to the cultures in the desert and Upper Egypt, little care was taken in shaping and decoration. The coarse clay was left plain or coated with a red slip and lightly polished. Bowls were the most common shape. Small cups with knobbed feet (bottom centre) were rare and might have been lamps.

Catalog: Fayum Kom W, Fayum Neolithic, EA58690, EA58692

Fayum Kom K, Silos 60 and 64, Fayum Neolithic, EA58693, EA58694

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Desert beginnings

Desert Neolithic of Nabta Playa, 8 600 BC - 4 400 BC

The origins of Egyptian civilisation can be traced back to early hunting and gathering herders who colonised the desert from about 8 600 BC, until the climate forced them to the Nile 4 000 years later. The first people to reach Nabta Playa brought with them some of the earliest pottery in Africa, and possibly Africa's first tamed cattle. Used for their milk and blood, rather than their meat, these cattle supplemented a diet of game and wild grasses.

Text above: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

First pottery, 8 600 BC.

The early inhabitants of Nabta made large pottery bowls from local clays, covering the entire surface with impressed decorations using various tools.

The notched rectangle of eggshell shown second from the left in the top row was pressed into the wet clay and pivoted over the pot's surface to create a dotted design.

Perforated pottery disks, often with notched edges, could also be mounted on a stick and rolled over the clay. The designs imitate basketry. The pots must have been important for display or rituals, ( or storage - Don ) as no evidence of cooking can be seen.

Catalog: Nabta E79-8, E80-4, Early Neolithic, EA76847, EA76848, EA82302

Nabta E75-9, E91-1, Early Neolithic, EA76925, EA76942

Nabta E00-1, E79-6, Early Neolithic, EA81424, EA81423

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Early Neolithic Climatic Optimum, 7 050 BC - 6 100 BC

For more than 1 000 years arid conditions made life in the desert difficult, but at about 7 050 BC, the climate became ideal for settlement. With a permanent water supply and fertile grasslands, people could stay in the desert all year round. They built huts, dug wells and made storage pits to hold a variety of wild grasses. Some grasses, like sorghum, they may even have cultivated.

Text above: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Pottery bowl fragments, 7 050 BC - 6 100 BC

Pottery was more common during the Early Neolithic wet phase. It was still valued as the holes for mending show. Decorative bands, with designs similar to ostrich eggshell containers, were now added around the rim. The dotted wavy line pattern indicates contact with early cultures in the Sudan, where this design was widespread.

Catalog: Nabta E75-6, Early Neolithic EA76916

Nabta E91-1, Early Neolithic, EA76946, EA76941, EA76943, EA76944

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Ostrich eggshell containers, 7 050 BC - 6 100 BC

Once carefully emptied, ostrich eggs made light but strong containers and canteens. They were used frequently by these mobile people, especially in the Early Neolithic period. Some eggshell containers were etched with intricate designs that were copied in pottery.

Catalog: Nabta E79-8, Early Neolithic, EA81422

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Flint implements, 7 050 BC - 6 100 BC

Tiny triangles, semi-circles and trapezoids of flint were fitted into wooden handles to make a variety of composite tools. Their standard size and shapes meant they could be re-arranged or replaced when dull or broken. Microlithic technology was used across North Africa for more than 10 000 years and continued at Nabta Playa until the late phase.

Catalog: Nabta E80-4, E79-6, E75-6, Early Neolithic, EA82315, EA82325, EA82328

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

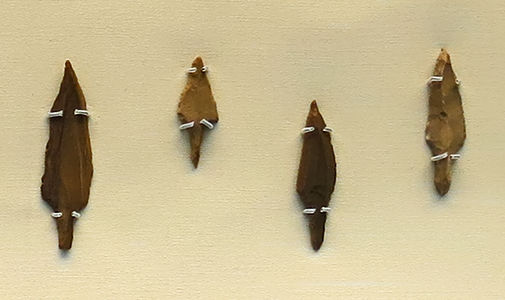

Arrowheads, 7 050 BC - 6 100 BC

Hunted animals were an important part of the diet. Special types of full-sized arrowheads, called Ounan points, ( or rather Ounanian-Harifian points, see the explanation below - Don ) were developed at this time specifically for hunting. The pointed tang allowed them to be rapidly inserted into a reed shaft when the need arose.

Catalog: Nabta E94-4, Early Neolithic, EA82303-EA82306

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

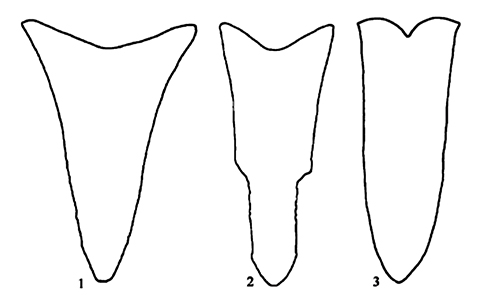

Ounan Point

This is a classic Ounan point from northern Mali (8 cm long).

The Ounanian point was first recognised by Breuil in 1930 at Ounan to the south of Taodeni in northern Mali from a surface collection of tools made from quartzite, which he ascribed to the Epi-Palaeolithic.

Made on blades, these specialised tools have had the proximal end modified by steep retouch to form a narrow perçoir - like tang or shank and shoulders, or more usually a single shoulder. Very often, this tang is incurved towards the shouldered edge of the tool.

Since the distal end is generally pointed, either naturally or by retouch, the tool is more probably a specialised form of projectile point rather than a perçoir, and the pointed tang would have served as an aid to hafting or perhaps in the case of the incurved examples as some kind of barb. Ounanian Points are the hallmark of the Epipaleolithic in the central Sahara, the Sahel and northern Sudan, and are dated between 8 000 BC and 4 000 BC.

Photo: © Katzman, Aggsbach's Paleolithic Blog

Source and text: http://www.aggsbach.de/2012/04/ounan-points-revisited/

The story of Ounan points is a little more complicated than the display at the British Museum has space to elucidate. I am indebted to Katzman, of Aggsbach's Paleolithic Blog, for explaining to me (P.C., 2016 ) the subtleties of the situation.

The 'Ounan' points from Nabta Playa are in fact a melding of the characteristics of the Harifian Points and the Ounan Points, known as Ounanian-Harifian points, see below.

Two classic Ounanian points from the Western Sahara on the left side, two classic Harifian Points from the Sinai on the right side, and in between some Ounanian-Harifian Points from Egypt

Photo: by courtesy of © Katzman, Aggsbach's Paleolithic Blog

Middle Neolithic, 6 000 BC - 5 500 BC

After a period of drought, people returned to Nabta with an important new addition: domestic sheep and goats. Introduced from the Near East, these animals eventually become the primary meat source. These herders lived in small, dispersed villages of round huts with slab lined walls. They moved over the course of the year to be close to water or other resources.

Text above: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Pottery fragments, 6 000 BC - 5 500 BC

Interest in decorating pottery gradually diminished. Stamped designs became more widely spaced or were smoothed over to lessen their visual impact. Later on, the pottery became plain with decoration only at the rim.

Catalog: Nabta E75-E78, Middle Neolithic, EA76898, EA76900, EA76902, Nabta E00-1, Middle Neolithic EA76969

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

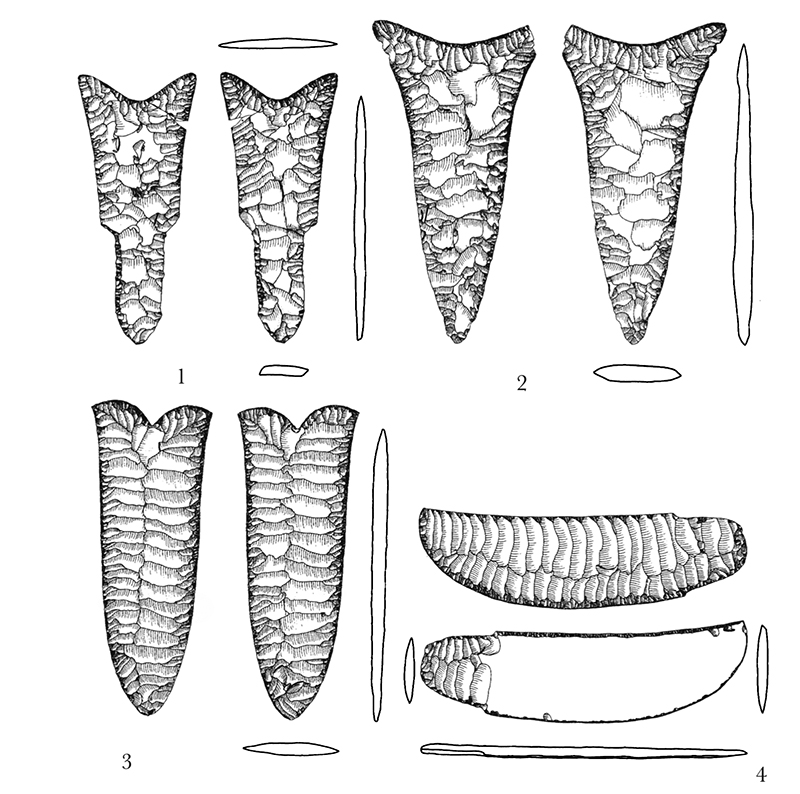

Flint implements, 6 000 BC - 5 500 BC

Along with sheep and goats, new ways of working flint were also introduced from the Near East. This new bifacial technique used pressure to remove flakes from both sides of tools, making them thin but strong.

Leaf -shaped arrowheads and knives made in this way became widespread in the northern Sahara, as microlithic technology was gradually abandoned.

Catalog: Nabta, Middle Neolithic, EA82314, EA82316,EA82317, EA82318, EA82322

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Grinding stones, 6 000 BC - 5 500 BC

Seeds and wild grasses were processed with round or oval grinders ( manos ) of hard quartzitic sandstone. These were rubbed against a larger mill stone to make flour. A depression in the lower stone' s surface prevented spillage The abundance of grinding stones shows that plant food made up a significant part of the diet at this time.

Catalog: Nabta E75, E76, Middle Neolithic, EA82298

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Late Neolithic, 5 400 BC - 4 400 BC

After another dry phase people returned to the desert, but the climate was becoming increasingly arid. This forced the herders to roam more widely and the large seasonal lake at Nabta Playa became a place where the dispersed groups gathered for ceremonies.

Stone alignments and calendar circles built for these events reflect the increased social organisation at this time of environmental stress.

Text above: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Late Neolithic Pottery, 5 400 BC - 4 400 BC

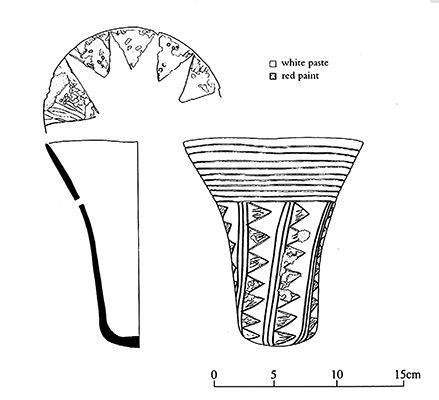

Pottery with blackened rims or rippled surfaces appeared in the last phases of habitation at Nabta. Ripples were made by combing the wet clay and then polishing the pot's surface. Incised decoration was now limited to elaborate tulip-shaped beakers which were placed with the dead in large family graves.

Catalog: Nabta E00-1, Late Neolithic, EA76973, EA76974, EA82300, Nabta E00-5 tumulus, Final Neolithic, EA82301

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Ground stone axe, 5 400 BC - 4 400 BC

Hard stone cobbles were laboriously ground against an abrasive stone to shape and sharpen them for use as axes. They were then polished to increase mechanical strength.

Employed for chopping and cutting, these axes became important parts of the tool kit of later agricultural communities along the Nile.

Catalog: Nabta, Late Neolithic, EA82903

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Arrowheads and knife, 5 400 BC - 4 400 BC

Hunting remained an important source of food for the desert herders. The quality and beauty of their hunting equipment was a matter of prestige.

Concave base arrowheads were probably invented in the Sahara, but gained popularity among later cultures in both Upper and Lower Egypt.

Catalog: Nabta, Late Neolithic, EA82312, EA82904, EA82902, EA82329, EA82313, EA82319, EA82321, EA82901

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

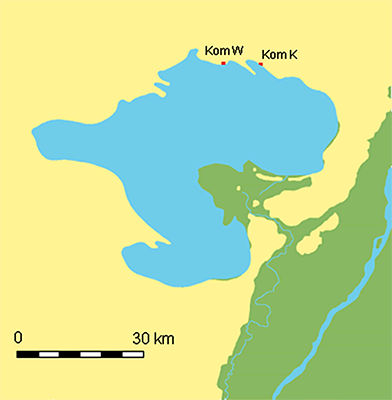

The Fayum Neolithic

The beginnings of agriculture, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

The changing climate caused movements of people east and west. In the Fayum Oasis, those living around Lake Qarun (Birket-el-Qerun) absorbed elements from both directions.

From the Near East they adopted the cultivation of barley and emmer wheat, and were the first to do so in Egypt. From the desert they took innovations that helped them as mobile hunters and fishermen. Often shifting their location to exploit different resources, they stored their harvest and other possessions in basket-lined silos, grouped together on high ground. The contents of these silos give us insight into life in early Fayum.

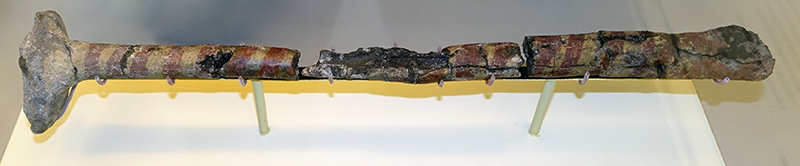

The Fayum Neolithic - Sickle with handle, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

The adoption of farming required new tools. The most important of these was the sickle for harvesting crops. This complete example was found within a storage silo.

The three blades are set into a groove in the wooden handle and held in place with resin. Two show signs of intensive usage. The uppermost blade is much less worn and must have been a replacement for one that had broken.

Catalog: Fayum Kom K, Silo 51, Fayum Neolithic, EA58701

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

A scenic view of Faiyum Oasis in 2008

The city of Itj-tawy, which was the political and administrative capital during the Middle Kingdom period of Egypt, was located very close to this oasis.

Faiyum Oasis is located about 130 kilometres southwest of Cairo.

Photo and text: cynic zagor (Zorbey Tunçer)

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

When the Mediterranean Sea was a hot dry hollow near the end of the Messinian Salinity Crisis in the late Miocene, Faiyum was a dry hollow, and the Nile flowed past it at the bottom of a canyon which was 2400 metres deep or more where Cairo is today. At the time, the Mediterranean Sea was a deep dry basin bottoming at some places 3 km to 5 km below sea level. After the Mediterranean reflooded at the end of the Miocene, 5.33 million years ago with the Zanclean flood, the Nile canyon became an arm of the sea reaching inland further than Aswan. Over geological time that sea arm gradually filled with silt and became the Nile valley.Text above: Wikipedia

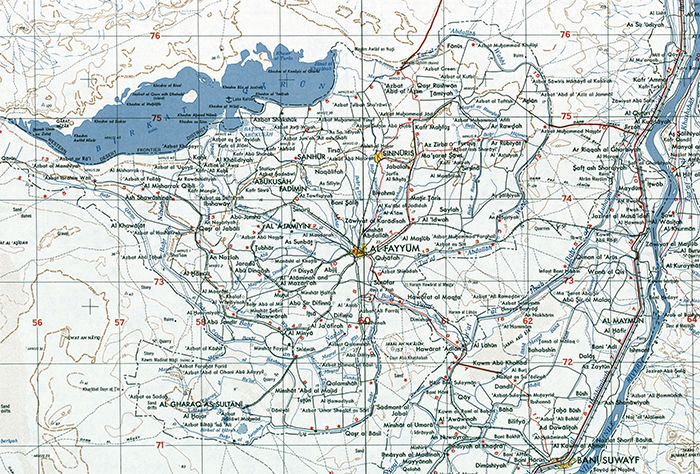

Map sheet showing Fayyum Oasis, Egypt, 1953, and the lake which supplies its water, Birket-el-Qerun.

Eventually the Nile valley bed silted up high enough to let the Nile in flood overflow into the Faiyum hollow and make a lake in it. The lake is first recorded from about 3 000 BC, around the time of Menes (Narmer). However, for the most part it would only be filled with high flood waters. The lake was bordered by neolithic settlements, and the town of Crocodilopolis grew up on the south where the higher ground created a ridge.

In 2 300 BC, the waterway from the Nile to the natural lake was widened and deepened to make a canal which is now known as the Bahr Yussef. This canal fed into the lake. This was meant to serve three purposes: control the flooding of the Nile, regulate the water level of the Nile during dry seasons, and serve the surrounding area with irrigation. There is evidence of ancient Egyptian pharaohs of the twelfth dynasty using the natural lake of Faiyum as a reservoir to store surpluses of water for use during the dry periods.

Photo: US Army Map Service, Corps of Engineers

Permission: Public Domain

The immense waterworks undertaken by the ancient Egyptian pharaohs of the twelfth dynasty to transform the lake into a huge water reservoir gave the impression that the lake itself was an artificial excavation, as reported by classic geographers and travellers. The lake was eventually abandoned due to the nearest branch of the Nile dwindling in size from 230 BC.

The lake at Fayum today, Lake Qarun (Birket-el-Qerun), much reduced from former times.

Photo: Hussain92

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Faiyum was known to the ancient Egyptians as the twenty-first nome of Upper Egypt, Atef-Pehu ('Northern Sycomore'). In ancient Egyptian times, its capital was Sh-d-y-t (usually written 'Shedyt'), called by the Greeks Crocodilopolis, and refounded by Ptolemy II as Arsinoe.

This region has the earliest evidence for farming in Egypt, and was a centre of royal pyramid and tomb-building in the Twelfth dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, and again during the rule of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Faiyum became one of the breadbaskets of the Roman world.

Map showing the extent of the lake in the Pleistocene (left) and during the Neolithic.

Photo after: Caton-Thompson and Gardner (1934)

Source: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/maps/fayum.html

Map showing the extent of the lake in Dynastic times, left, and in 1925.

Photo after: Caton-Thompson and Gardner (1934)

Source: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/maps/fayum.html

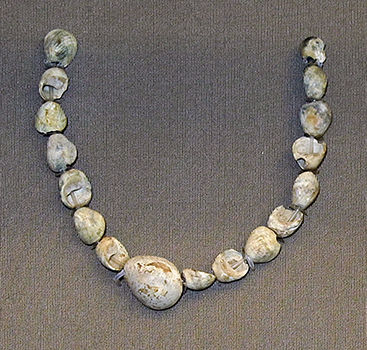

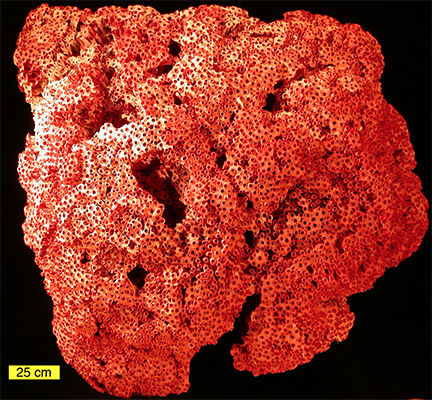

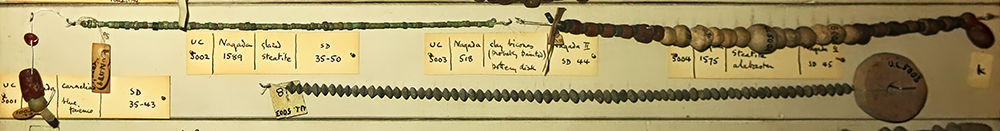

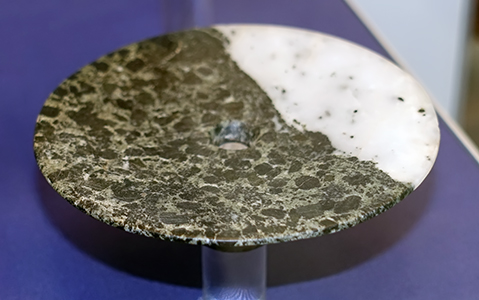

The Fayum Neolithic - Beads, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Beads from the Fayum Neolithic, including ostrich egg shell beads, amazon stone (green microcline feldspar, probably from Ethiopian deposits) and stone.

Catalog: Fayum Neolithic, UC2536, UC2544, UC2565, UC2565A, UC3747

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, Petrie Museum, London, England

Text: Card / online catalogue, the Petrie Museum, © 2015 UCL. CC BY-NC-SA license.

The Fayum Neolithic - Farming tools: hoes and axes, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Along with wheat and barley, the tools for farming these crops were adopted from the Levant. These include the sickle for harvesting, the hoe for tilling the soil and the flint axe.

Their shape and appearance, painstakingly pressure-flaked on both sides, must have been a matter of prestige. Other tools were more economically made, used and then discarded.

Catalog: Fayum, Fayum Neolithic, EA58706, EA58710, EA58717

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Fayum Neolithic - Sickle blades, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Sickles were used to reap a variety of crops or wild grasses. The cutting edge was made fine or coarse depending on the intended purpose. The shiny area visible on the blade to the right is called sickle gloss.

It is a residue that has accumulated from cutting the stems of cereals and grasses that are rich in silica. ( not visible in my photo - perhaps they mean the one on the left, which exhibits sickle gloss - Don )

Catalog: Fayum, Fayum Neolithic, EA58715 - EA58716

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2018

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Fayum Neolithic - Ground stone Celts, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Celts or axes made of hard stones, ground to shape, were an important part of the tool kit. They were used for chopping and cutting wood, but could also till the soil.

The labour-intensive combination of chipping and polishing used to make these axes gave them great tensile strength. Such axes have a long history in North Africa.

Catalog: Fayum, Kasr el Sagha, Fayum Neolithic, EA58703, EA58704, EA58705

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Fayum Neolithic - Tools for hunting: arrowheads, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Several types of arrowheads were used by the Fayum people. The point with notched edges was borrowed from the Levant. Tanged points were rare.

Most characteristic were those with concave bases. These were effective weapons. On the shores of the Fayum lake, examples were found embedded in the bones of a hippopotamus and elephant.

Catalog: Fayum, Fayum Neolithic, EA83063, EA58740, EA58744, EA58733, EA58736, EA58738

( note that the superb example in the middle of the bottom row is clearly marked as 58737 - Don )

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Fayum Neolithic - Tools for hunting: arrowheads, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Concave base arrowheads were attached to shafts using a resin adhesive.

The 'wings' at the base were intended to strengthen this join.

They were originally covered entirely by the adhesive, as shown at left.

Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Poster, British Museum

Text: Poster at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The Fayum Neolithic - Tools for hunting: knife for butchery, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Knives for hunting and butchery were always in demand. This example has been worked to a fine edge on both sides.

Catalog: Fayum, Fayum Neolithic, EA58724

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Fayum Neolithic - Tools for hunting: a waisted stone, 5 200 - 4 200 BC

Small, oval-shaped pieces of limestone with a groove around the middle were numerous at Fayum sites. They may have been used as hammer stones or with sling shots.

( this waisted stone is exactly the right shape for a net weight, and its small size indicates that it (and many others) would have been used on the edges of a cast net (rather than a drag net, which needs heavier weights as well as floats) to catch fish from the nearby lake. They would have been used again and again, being transferred to a new net when the old one needed to be replaced.

The groove serves to accept a tightly knotted cord around the waist of the stone, which is then attached to the edge of the net. This is a standard design for a net weight, or, indeed, with a much larger rock and strong rope, as an anchor for a small boat.

A circular cast net cannot be used effectively in water that is deeper than its radius, but is ideal for catching small fish in up to waist deep water when the size of mesh is adapted for the intended catch. The fish can either be eaten or used as bait for larger fish using a rod and line - Don )

Catalog: Fayum, Kom K, Fayum Neolithic, EA58760

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Source: Original, British Museum

Text: Card at the British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

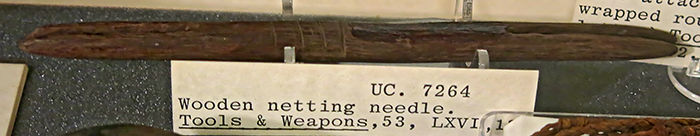

Wooden netting needle, 138 mm.

Netting needles are essential for making nets for any purpose, whether for net bags or for fishing or bird nets.

From Lahun, which is a site beside the Bahr Yussef, the canal connecting Lake Qarun to the Nile. Fish nets used there would possibly have been placed across the entire narrow waterway to catch fish moving up or down the waterway.

Place: Lahun (Fayum (governorate) / Egypt D - K / Egypt)

Period: Late Middle Kingdom, circa 1850 BC - 1750 BC

Catalog: UC7264

Photo (upper): Don Hitchcock 2015

Photo (lower): © 2015 University College London. This work by the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL is licensed under a CC BY-NC_SA licence.

Text: http://petriecat.museums.ucl.ac.uk/

Source: Original, Petrie Museum, London, England

Text: Card / online catalogue, the Petrie Museum, © 2015 UCL. CC BY-NC-SA license.

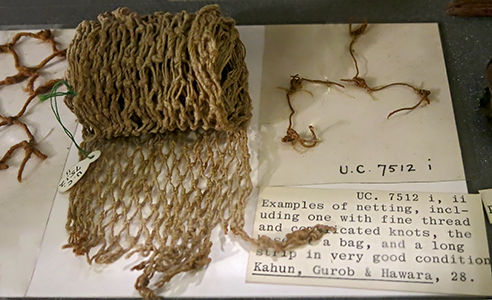

(left) Linen net from Lahun (Fayum governorate), late Middle Kingdom.

( this net seems to have been made using the classic sheet bend knot, except on what looks like the original edge of the net on the left of the image, where a different knot has been used. The size of mesh would have been ideal to catch larger fish, although the card with it says that it formed the base of a netting bag. A peg board would have had to have been used to create such a uniform net size - Don )

(right) A roll of linen net in good condition, also from Lahun, late Middle Kingdom.

Place: Lahun (Fayum (governorate) / Egypt D - K / Egypt)

Period: Late Middle Kingdom, circa 1850 BC - 1750 BC

Catalog: UC7512

Photo: Don Hitchcock 2015

Text: http://petriecat.museums.ucl.ac.uk/

Source: Original, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London

Valley of Sacrifices at Nabta Playa

4600 BC - 4400 BC

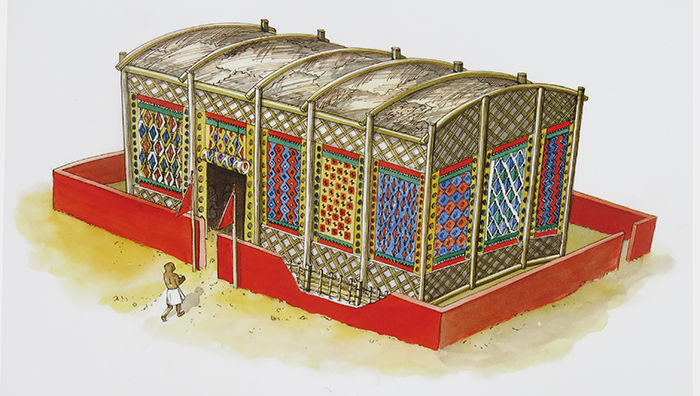

As the climate turned increasingly hostile, from about 4 600 BC, Nabta Playa became a ceremonial centre where scattered groups could gather. The wadi (valley) that fed rain water into the playa (seasonal lake) is called the Valley of Sacrifices. It contains a remarkable collection of stone monuments revealing the desert population's efforts to secure divine influence in their struggle for survival.

Erected near the centre of the wadi was a small ring of upright stones, with sets of larger slabs positioned to locate sunrise at the summer solstice. This was the beginning of the rainy season and probably signalled the start of the ceremonies.

To the north, stone mounds (tumuli) marked the burials of sacrificed animals. Further south, huge slabs were set up in long lines, possibly positioned to aid astronomical observations. Near them other clusters of megaliths may have commemorated the ancestral dead. This ceremonial complex reflects a structured society, with priests or shamans to lead the rituals and chiefs to command the labour.

View of the calendar circle in situ at Nabta Playa.

Photo: Courtesy of the combined Prehistoric Expedition and Wendorf Archive (British Museum) © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Source: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

Text: poster at the Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Nabta Playa Calendar Circle, reconstructed at Aswan Nubia museum.

Photo: Raymbetz

Permission: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Map of the Valley of Sacrifices at Nabta Playa.

Archaeological discoveries reveal that these prehistoric peoples led livelihoods seemingly at a higher level of organisation than their contemporaries who lived closer to the Nile Valley. The people of Nabta Playa had above-ground and below-ground stone construction, villages designed in pre-planned arrangements, and deep wells that held water throughout the year.

Findings also indicate that the region was occupied only seasonally, most likely only in the summer period, when the local lake filled with water for grazing cattle.

Comparative research indicated that the indigenous inhabitants may have a significantly more advanced knowledge of astronomy and mathematics than previously thought possible.

By the 6th millennium BC, evidence of a prehistoric religion or cult appears, with a number of sacrificed cattle buried in stone-roofed chambers lined with clay. It has been suggested that the associated cattle cult indicated in Nabta Playa marks an early evolution of Ancient Egypt's Hathor cult.

By the 5th millennium BC these peoples had fashioned what may be among the world's earliest known archeoastronomical devices (roughly contemporary to the Goseck circle in Germany and the Mnajdra megalithic temple complex in Malta). These include alignments of stones that may have indicated the rising of certain stars and a 'calendar circle' that indicates the approximate direction of summer solstice sunrise. 'Calendar circle' may be a misnomer as the spaces between the pairs of stones in the gates are a bit too wide, and the distances between the gates are too short for accurate calendar measurements." An inventory of Egyptian archaeoastronomical sites for the UNESCO World Heritage Convention evaluated Nabta Playa as having 'hypothetical solar and stellar alignments.'

Claims for early alignments and star maps

Astrophysicist Thomas G. Brophy suggests the hypothesis that the southerly line of three stones inside the Calendar Circle represented the three stars of Orion’s Belt and the other three stones inside the calendar circle represented the shoulders and head stars of Orion as they appeared in the sky. These correspondences were for two dates—circa 4 800 BC and at precessional opposition - representing how the sky 'moves' long term. Brophy proposes that the circle was constructed and used circa the later date, and the dual date representation was a conceptual representation of the motion of the sky over a precession cycle.

Near the Calendar Circle, which is made of smaller stones, there are alignments of large megalithic stones. The southerly lines of these megaliths, Brophy shows, aligned to the same stars as represented in the Calendar Circle, all at the same epoch, circa 6 270 BC. The Calendar Circle correlation with Orion's belt occurred between 6 400 BC and 4 900 BC, matching the radio-carbon dating of campfires around the circle.

Photo: Courtesy of the combined Prehistoric Expedition and Wendorf Archive (British Museum) © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Source: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

Text: poster at the Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Additional text: Wikipedia

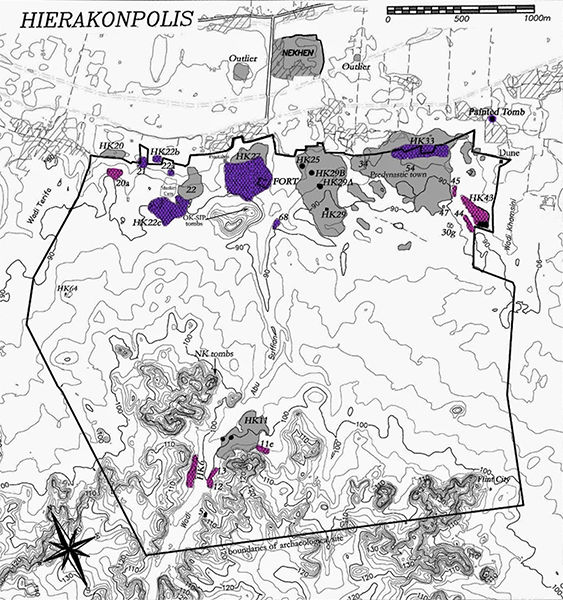

Beginnings in Upper Egypt

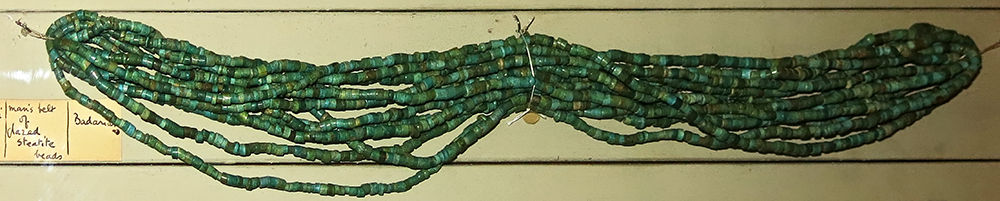

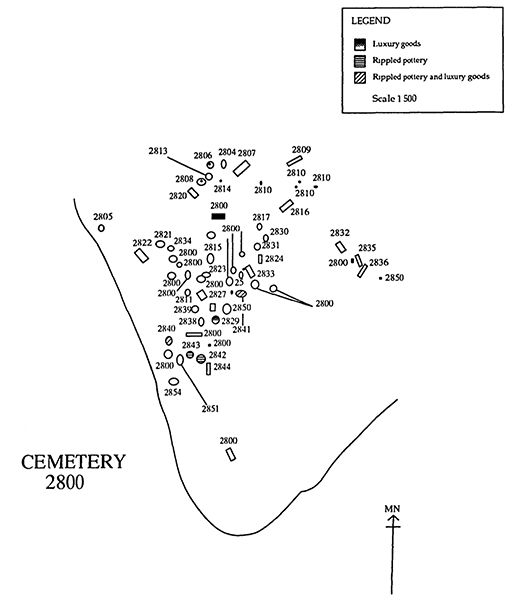

Badarian: 4 400 - 4 000 BC

The earliest agricultural society in Upper Egypt is called Badarian after sites excavated by a team part-sponsored by the British Museum in the 1920s.Text above: poster at the Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Badarian farmers lived in small villages and cultivated wheat, barley and flax. Using the desert's edge for burials, they placed distinctive pieces of 'rippled' pots and other objects in the graves. Their pottery and flint tools show links to earlier desert dwellers, while their burial practices and imagery anticipate the Predynastic period that followed.

El Badari contains an archaeological site with numerous Predynastic cemeteries (notably Mostagedda, Deir Tasa and the cemetery of El Badari itself), as well as at least one early Predynastic settlement at Hammamia. The finds from El Badari form the original basis for the Badarian culture, the earliest phase of the Upper Egyptian Predynastic period. The area stretches for 30 km along the east bank of the Nile, and was first excavated by Guy Brunton and Gertrude Caton-Thompson between 1922 and 1931. Most of the cemeteries in the Badarian region have yielded distinctive pottery vessels (particularly red-polished ware with blackened tops), as well as terracotta and ivory anthropomorphic figures, slate palettes, stone vases and flint tools. The contents of Predynastic cemeteries at El Badari have been subjected to a number of statistical analyses attempting to clarify the chronology and social history of the Badarian period.Text above: Wikipedia

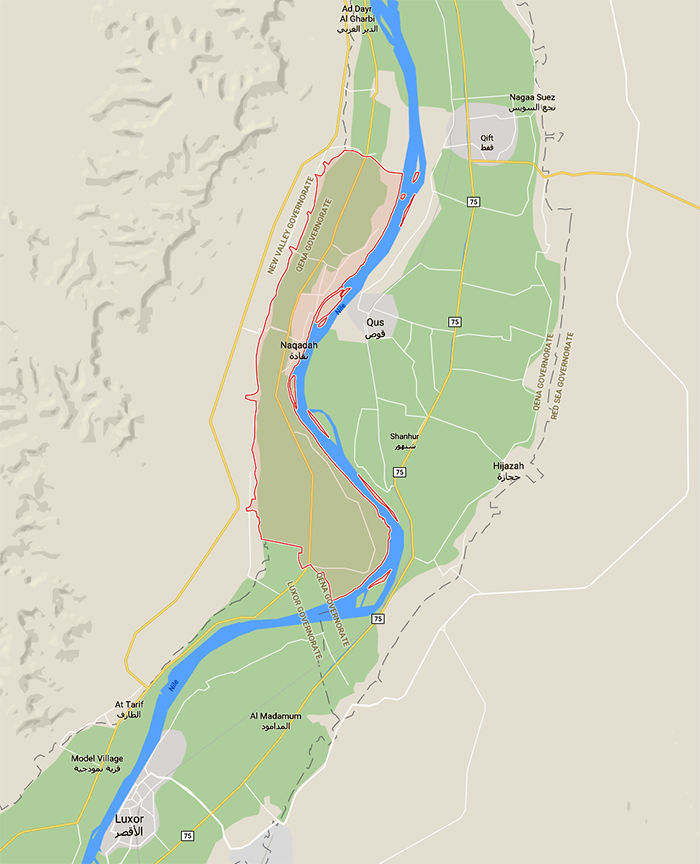

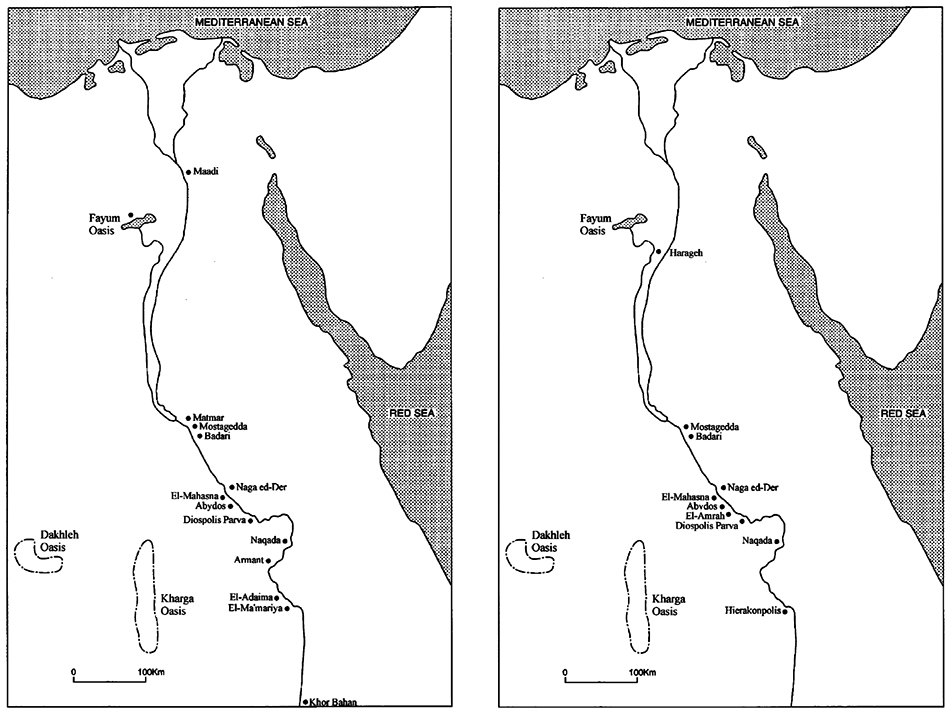

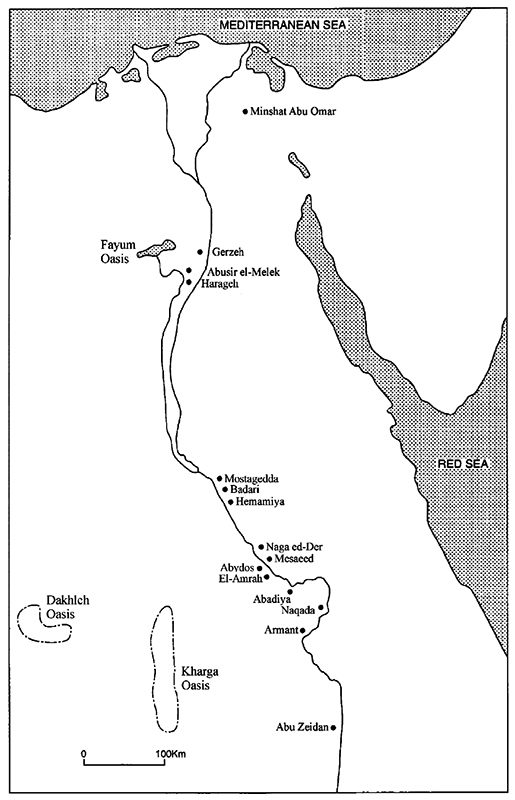

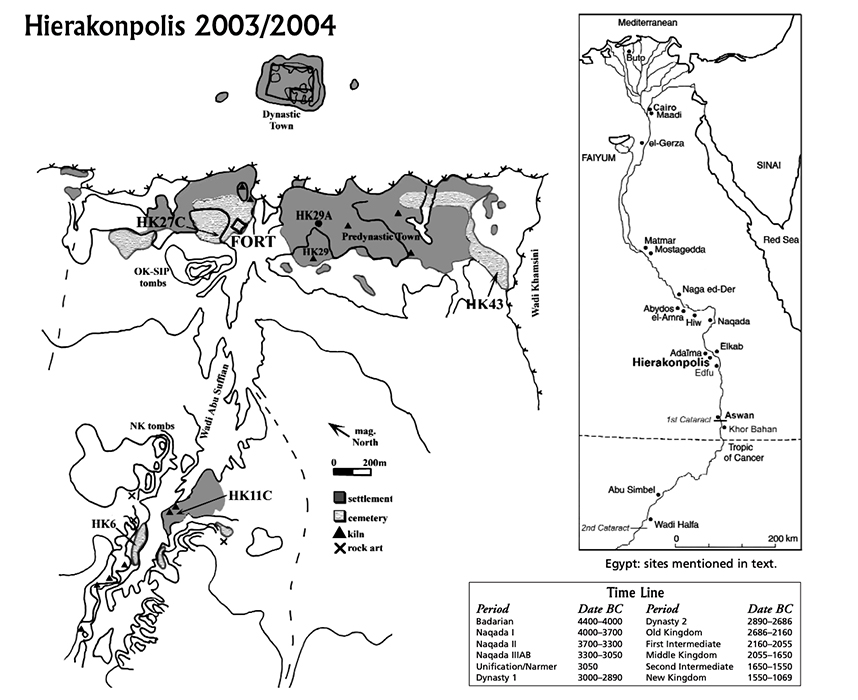

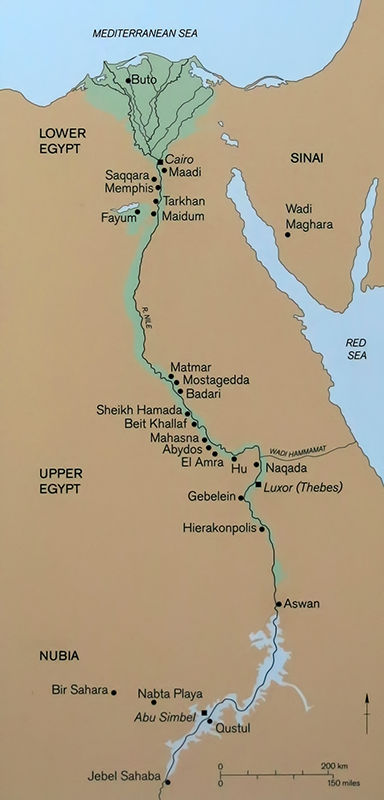

Map of the major sites and places in Early Egypt.

This map shows the position of the important Badarian sites of Mostagedda and Badari.

Photo: Poster, British Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Rephotography: Don Hitchcock 2015

Text: poster at the Museum © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Despite the existence of some excavated settlement sites, the Badarian culture is mainly known from cemeteries in the low desert. All graves are simple pit burials, often incorporating a mat on which the body was placed. Bodies are normally in a loosely contracted position, on the left side, head to the south, looking west. Graves of very young children are lacking. There is sufficient evidence to show that these were buried within the settlement, or rather within parts of the settlements that were no longer used.Text above: Shaw (2000)

Analysis of Badarian grave goods demonstrates an unequal distribution of wealth. In addition, the wealthier graves tend to be separated in one part of the cemetery. This clearly indicates social stratification, which still seems limited at this point in Egyptian prehistory, but which became increasingly important throughout the subsequent Naqada Period.

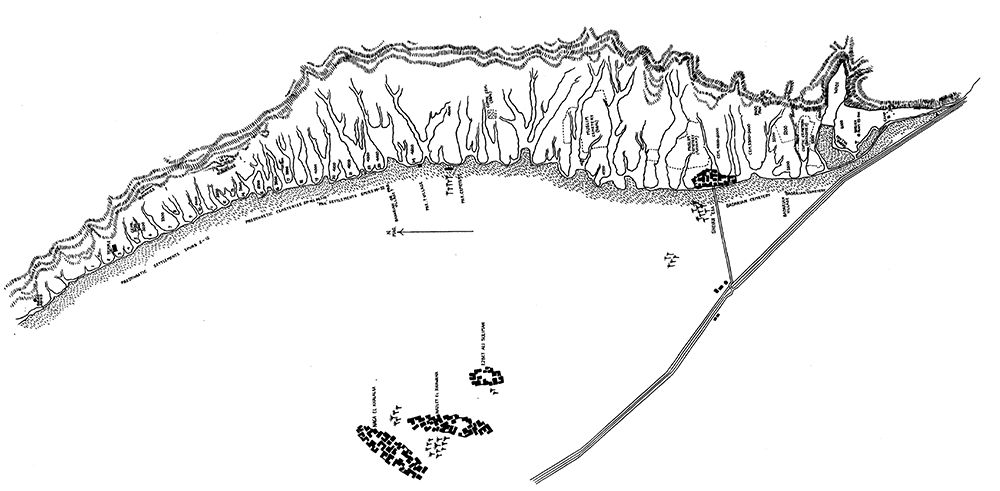

Sketch map of the Badari District.

Photo: Brunton and Caton-Thompson (1928)

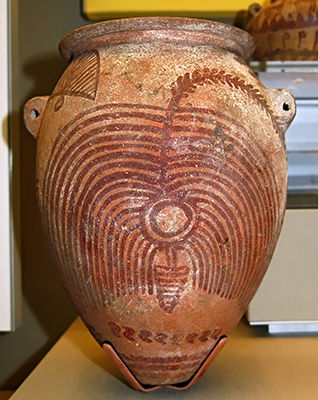

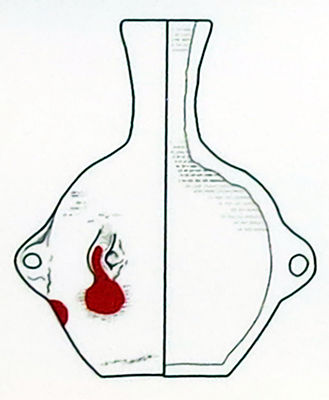

The pottery that accompanies the dead in their graves is the most characteristic element of the Badarian culture. All pottery is made by hand, from Nile silts, which, except for the very fine wares, always has a very fine organic temper. This very characteristic temper is always finer than that used for the so-called rough ware during the Naqada Period. For their best products, the Badarian potters spared no efforts in refining the clay and obtaining very thin walls, which have never been equalled in any subsequent period of the Egyptian past.Text above: Brunton and Caton-Thompson (1928)

( All potters can understand this drive for thinness of the walls of vessels. It is an indicator of the skill of the potter, and has the advantage of using less materials, but more importantly of providing significantly different and valuable trade goods which are lighter to transport - Don )

Pottery shapes are simple, mainly comprising cups and bowls with direct rims and rounded base. A significant proportion of the vessels are black topped, but they generally have a more brownish surface than the Naqada I black-topped pottery. Red slip, with which the Naqada I black-topped pottery is covered, is far more exceptional for the Badarian. The most characteristic element of the Badarian pottery is the 'rippled surface' that is present on the finest pottery, meaning that the surface has been combed with an instrument and afterwards polished, resulting in a very decorative effect.

Carinated vessels (Carinate is a shape in pottery, glassware and artistic design usually applied to amphorae or vases. The shape is defined by the joining of a rounded base to the sides of an inward sloping vessel. Wikipedia) are also considered highly characteristic of the culture, but decorated pottery is rare: occasionally, incised, white-filled, geometrical motifs have been applied, perhaps imitating basketry.

The lithic industry is mainly known from settlement sites, although the finest examples have been found in graves. It is principally a flake and blade industry, to which a limited number of remarkable bifacial worked tools are added. Predominant tools are end-scrapers, perforators, and retouched pieces. Bifacial tools consist mainly of axes, bifacial sickles, and concave-base arrowheads. It should also be noted that the characteristic side-blow flakes were also present in the Western Desert.

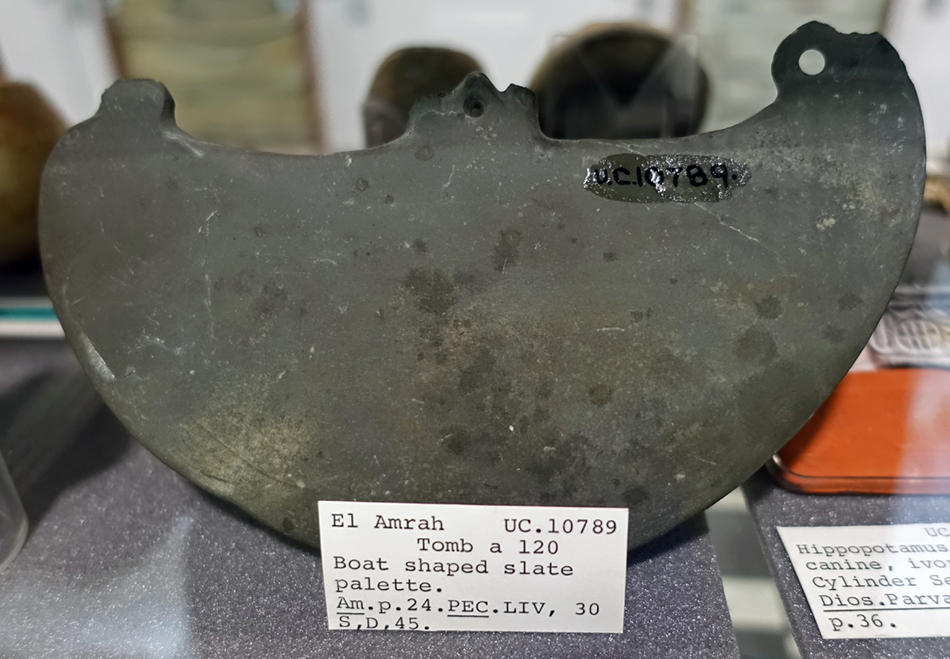

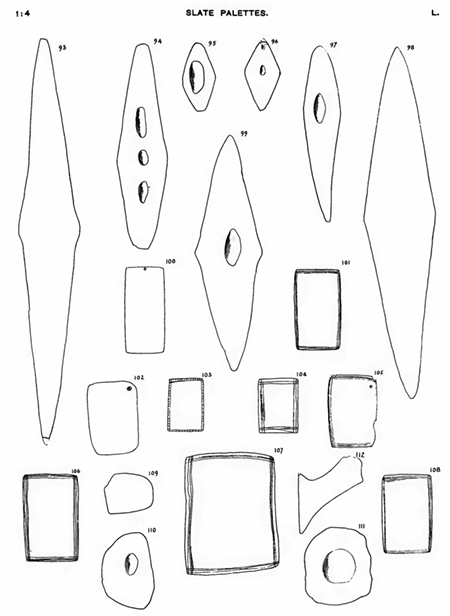

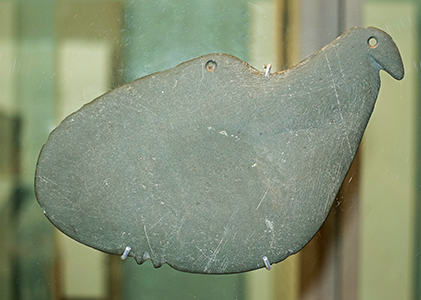

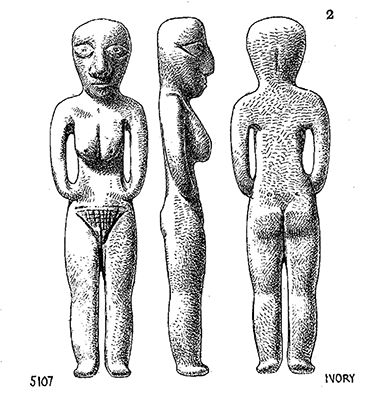

Other products of the Badarian culture include such personal items as hairpins, combs, bracelets, and beads in bone and ivory. The repertoire of greywacke cosmetic palettes was at this date limited to long rectangular or oval shapes, but they would later become very characteristic aspects of the Naqada culture, when they were produced in a great variety of shapes. A few clay and ivory female statuettes have been found, varying immensely in style from fairly realistic examples to others that are highly stylised. It should also be noted that hammered copper was present in limited quantities.

For a long time it was thought that the Badarian culture remained restricted to the Badari region. However, characteristic Badarian finds have also been made much further to the south, at Mahgar Dendera, Armant, Elkab, and Hierakonpolis, and also to the east, in the Wadi Hammamat.

Originally, the Badarian culture was considered a chronologically separate unit, out of which the Naqada culture developed. However, the situation is certainly far more complex. For instance, the Naqada period seems to be poorly represented in the Badari region; therefore, it has been suggested that the Badarian was largely contemporary with the Naqada I culture in the area to the south of the Badari region. How- ever, since a limited number of Badarian or Badarian-related artefacts have also been discovered south of Badari, it might instead be argued that the Badarian culture was present between at least the Badari region and Hierakonpolis.

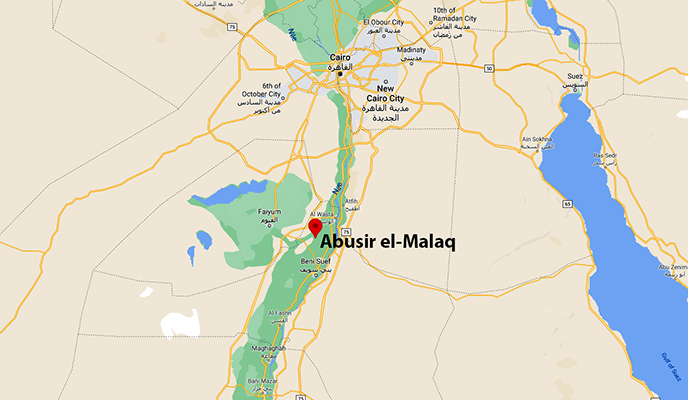

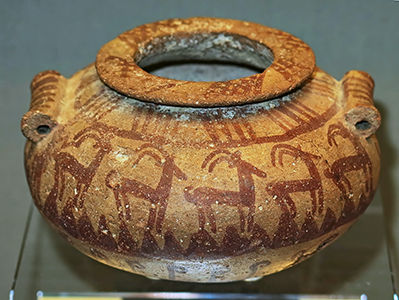

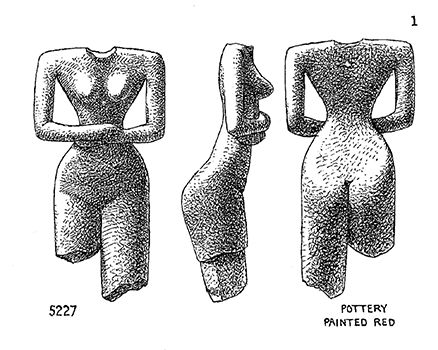

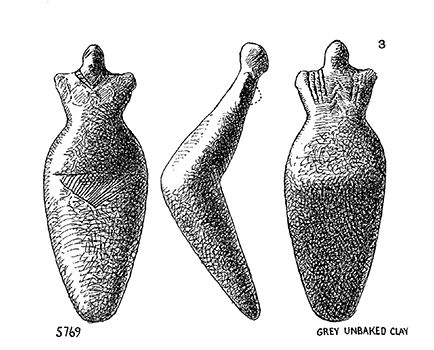

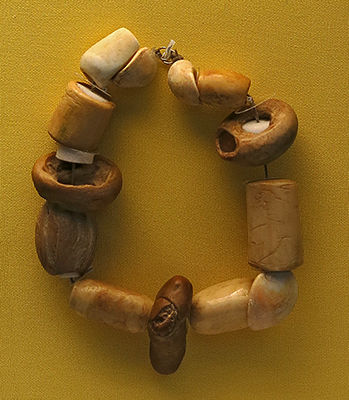

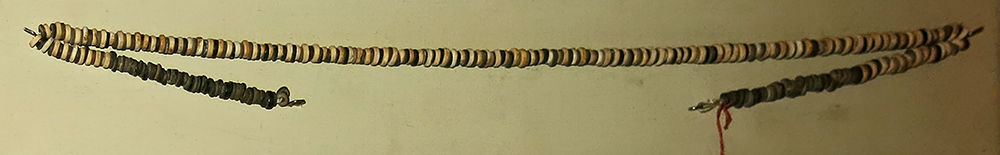

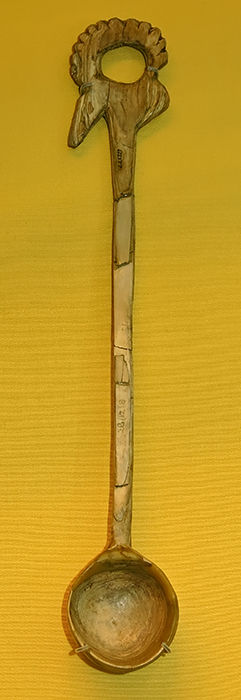

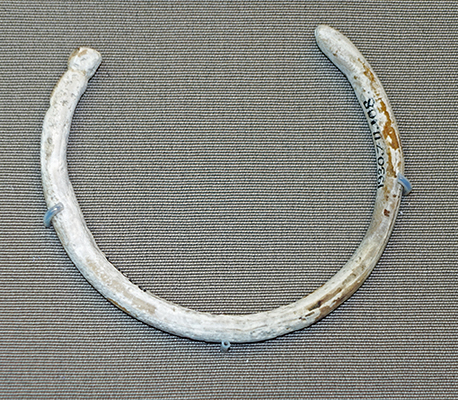

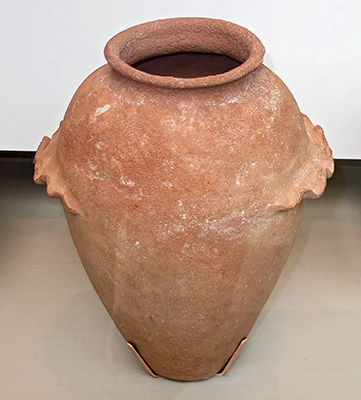

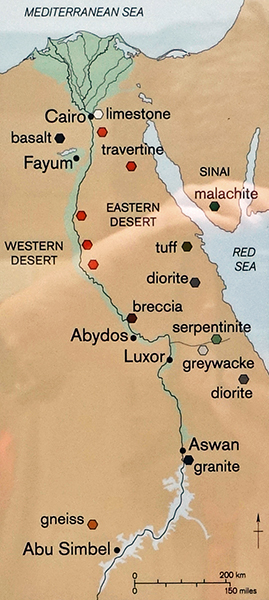

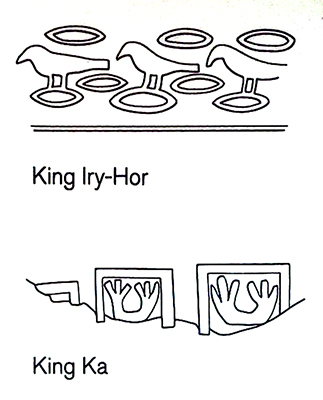

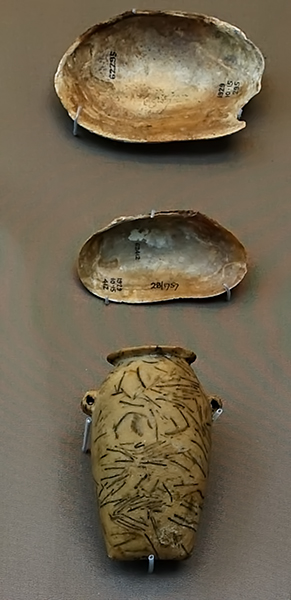

Unfortunately most of these finds are very limited in number, and a comparison with the lithic industry or the settlement ceramics from the Badari area is in most cases impossible or has not yet been published. The Badarian culture may, therefore, have been characterised by regional differences, the unit in the Badari region itself being the only one that has so far been properly investigated or attested. On the other hand, a more or less 'uniform' Badarian culture may have been represented over the whole area between Badari and Hierakonpolis, but, since the development of the Naqada culture took place more to the south, it seems quite possible that the Badarian survived for a longer time in the Badari region itself. The origins of the Badarian are equally problematic, having been sought in all directions. For a long time the Badarian was considered to have emerged from the south, because it was thought that the Badarians had 'poor knowledge' of chert, which would show that they came from the non-calcareous part of Egypt to the south; on the other hand, the origins of agriculture and animal husbandry were assumed to lie in the Near East. The theory that the Badarian originated in the south is, however, no longer accepted.